Chapter 19 Health promotion and education

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

The meaning of health

Health is a state of being to which most people aspire, yet a concept difficult to define, as personal meanings are enshrined in social structure, culture and belief systems. In 1946, the World Health Organization (WHO) described health as a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing, not merely the absence of disease or infirmity (WHO 1946). Health is thus seen as an ideal state of being which may be impossible to achieve. In an attempt to clarify the meaning of health, Seedhouse (1997) suggests that health is determined by the individual’s socioeconomic and cultural position, the context of which is determined by biological or chosen health potentials that provide an opportunity for the individual to aspire to achieve good health within the context of that health potential.

Reflective activity 19.1

What does being healthy mean to you? Jot down your personal definition of ‘being healthy’.

Health is to be viewed holistically, involving dimensions of health that are inextricably linked and include physical, mental, emotional, societal, sexual and spiritual health. If one dimension is negatively affected, this will have an impact on other dimensions (Ewles & Simnett 2003).

Models of health

Health models have been developed to try to explain why some individuals indulge in healthy behaviours and others do not. Well-known models include the Health Belief Model, formulated by Rosenstock in the 1960s and developed by Becker in the 1970s (Becker et al 1977), which was specifically designed to explain and predict preventive health behaviours. The Health Locus of Control, proposed by Rotter (1966), refers to the personal control over events that people believe they possess and is commonly used to explore how people’s beliefs about health and illness affect their behaviour. More information is available in the references and the website.

Reducing inequalities in health

Understanding the social, cultural and economic context of health and illness increases the opportunity for health promotion to be meaningful and effective. Poverty and deprivation are linked to poor health outcomes (Lewis 2007). In the UK, the National Health Service (NHS) was set up in 1948 to provide free medical care to the whole population and thereby achieve equality of access to health services for those in need. The hope was this would eliminate or greatly reduce inequalities in health. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this single approach to improving the health of those worst off in society did not succeed. The provision of health services cannot singularly solve inequality in health without addressing factors that influence ill health. Even when health improvements are made for all, inequalities continue to persist. Health inequalities are linked to wider determinants including income, housing, education and other opportunities which must be tackled so that health interventions can be effective (Office for National Statistics 2007).

A commitment to improve healthcare for all

Some, such as the Black Report, demonstrate substantial differences in mortality and morbidity rates between social class groups and made recommendations to address this (Black et al 1982) though these were not endorsed.

What is health promotion?

WHO defines health promotion as the process of enabling people to increase control over their health, and improve it. Integral to this definition is the notion of empowerment (WHO 1984). An example of empowerment in midwifery practice is the process by which the health professional uses strategies to enable the woman and her partner to lead and take control over their childbirth experience, resulting in development of personal empowerment, skills and control in everyday life.

Health develops by an ongoing relationship between the individual and their environment (Bauer et al 2006). The ultimate aim of health promotion is to provide opportunities for people to move within the context of their biological, intellectual and/or emotional potential (Seedhouse 1997). The momentum of movement, or indeed its maintenance, is likely to be successful only if the most appropriate avenue has been chosen to promote health, that is particular to or within the context of an individual’s life. A realistic approach to health promotion would include assessing the context of the woman’s living experience and identifying with the woman obstacles that inhibit the fulfilment of health potentials (see website for Case scenario 19.1).

Mental health promotion

Impaired mental health has a negative impact on emotional and physical health and reduces the individual’s capacity to cope with everyday life activities. The process and impact of postnatal depression is one example of how physical, spiritual, emotional and mental health are affected (see Chapter 69).

Sexual health promotion

Addressing sexual health issues may contribute to the overall wellbeing of the woman and family, therefore the midwife has an important role to play in this area of public health (see Chapter 57).

Sexuality and pregnancy

Sexuality in pregnancy is an important aspect of health that is not always addressed appropriately. Some women may feel embarrassed broaching this topic and some midwives, fearing intrusion of privacy, may also be reticent about discussing the issue. There may be religious, cultural and social taboos about having sexual intercourse during pregnancy, but some couples may have anxieties that could be relieved through frank discussion (see Chapter 13).

A health promotion model

A model may be described as a conceptual framework for organizing and integrating information offering causal links among a set of concepts believed to be related to a particular problem (Seedhouse 1997). There are several health promotion models that assist the practitioner in undertaking health promotion work. Here, only one model will be presented and explored in detail.

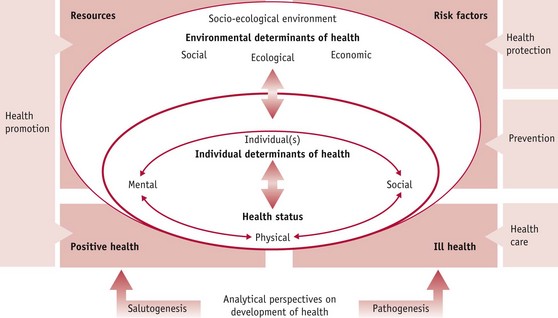

The health development model (Bauer et al 2006) in Figure 19.1 shows that health development is an ongoing process and health promotion intentional and planned. The model identifies three dimensions of health: physical, mental and social, and shows the interrelationship between health promotion and public health. The arrows pointing between these dimensions show that they are interdependent and interrelated. For example, exercising during pregnancy positively influences mental health and enables interaction and communication with others, thereby supporting social health.

When using the model it is useful to note that the health of an individual is not created and lived in isolation but results from a dynamic ongoing relationship with the relevant socio-ecological environment, including the cultural dimension (Bauer et al 2006). The health promotion approach taken must therefore reflect this. The model also identifies that an individual’s health status determines future health, and can be used as a predictor of health; however, a targeted health promotion approach can improve the health potential of that individual. For example, a mother who smokes may be helped to stop smoking during pregnancy and therefore enhance her life potential and that of her baby.

The majority of studies that set out to establish the determinants of health and ill health are set within the pathogenic paradigm (Tones & Green 2004). Pathogenesis analyses how risk factors of individuals and their environment lead to ill health. Antonovsky (1996) proposed that an additional perspective should be adopted by health promotion practitioners, that of salutogenesis, which examines how resources in human life support development towards positive health. Bauer et al (2006) suggest that in real life, salutogenesis and pathogenesis are simultaneous, complementary and interacting real-life processes.

Health promotion approaches

Ewles & Simnett (2003) identify five health promotion approaches:

Box 19.1

Health promotion in practice

Health promotion – community action

Health enhancement through community initiatives is well supported (DH 2008b). Health promotion has the potential to influence the health of present and future generations, with scope for a profound impact on reducing inequalities in health. Antenatal and postnatal care is predominantly provided in the community (historically recognized as a key arena to address these issues) where care is accessible with opportunity for flexibility at the point of delivery. Sure Start Children’s Centres provide a multi-agency, multidisciplinary focus to healthcare provision, located in the heart of the community, focusing services toward vulnerable women and their families.

Although traditionally midwives have provided postnatal care up until 28 days postpartum, the National Childbirth Trust found that women reported they had insufficient help and information between 11 to 30 days after birth, compared with the first 10 days (DH 2004). The National Service Framework for Children, Young People and Maternity Services, Standard 11 (DH 2004) suggests that midwifery-led services should be provided for the mother and her baby for at least a month after birth or discharge from hospital, and up to three months or longer depending on individual need.

This is a time when most families may be more receptive to health promotion, particularly with a new baby at home. The Royal College of Midwives (RCM) emphasizes the strength of midwifery within the community setting, encouraging the development of the midwife’s public health role (RCM 2000, 2001).

In 2007, asylum seeker applications in the UK totalled 23,430 (including dependants) (Home Office 2007). The Reproductive Health for Refugees Consortium made recommendations which included the need for culturally sensitive reproductive health, and appropriate referral systems, should obstetric emergencies arise. The health of pregnant asylum seekers is frequently compromised by lack of antenatal care, stressful, tortuous journeys from countries of origin, turmoil caused by war, oppression and poor nutrition. Their health disadvantage increases the risk of perinatal mortality and morbidity (Lewis 2007) and renders them ill-prepared for childbirth and parenting, particularly if antenatal care has been sparse (see Chapter 23).

It is for this reason that all pregnant mothers from countries where women may experience poorer overall general health, and who have not previously had a full medical examination in the UK, should have a medical history taken and clinical assessment made of their overall health by their obstetrician or GP (Lewis 2007). In particular, female asylum seekers arriving in the UK from certain countries in Africa and the Middle East may have undergone female genital mutilation (FGM) and as such require sensitive history-taking to ensure that an appropriate care plan is developed for pregnancy, labour and the postnatal period (see Chapter 58).

Health promotion in midwifery

Diet and nutrition

The midwife can provide effective health education in the area of diet and nutrition and may contribute to long-term healthy lifestyle changes (see Chapter 17). The health promotion approach chosen must be client-centred and include health education and empowerment. Behaviour change may also be necessary to promote immediate and long-term health. In an ever-changing healthcare climate where facts and knowledge change as new research emerges, the midwife must maintain current knowledge regarding diet and nutrition as the woman and her family naturally look to the midwife for advice.

New recommendations issued by the Food Standards Agency (FSA) on caffeine, for example, call for a reduction in caffeine consumption during pregnancy from no more than 300 mg to less than 200 mg (FSA 2008). This recommendation is based on two linked studies which showed that babies of pregnant women who consumed between 200 and 299 mg of caffeine per day were at an increased risk of fetal growth restriction which could result in low birthweight and/or miscarriage (CARE Study Group 2008).

Exercise during pregnancy

Most people are well aware of the benefits of exercise and sport, and many women are fitness conscious. Knowledge and understanding regarding exercise during pregnancy will assist the midwife in supporting women who wish to exercise during pregnancy (see Chapter 22).

Exercise has many positive benefits for the individual, including:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree