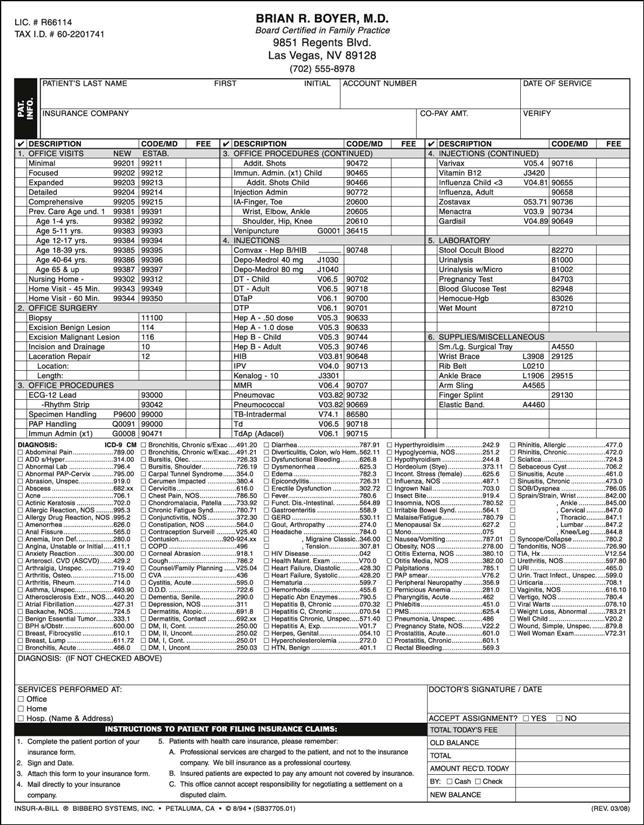

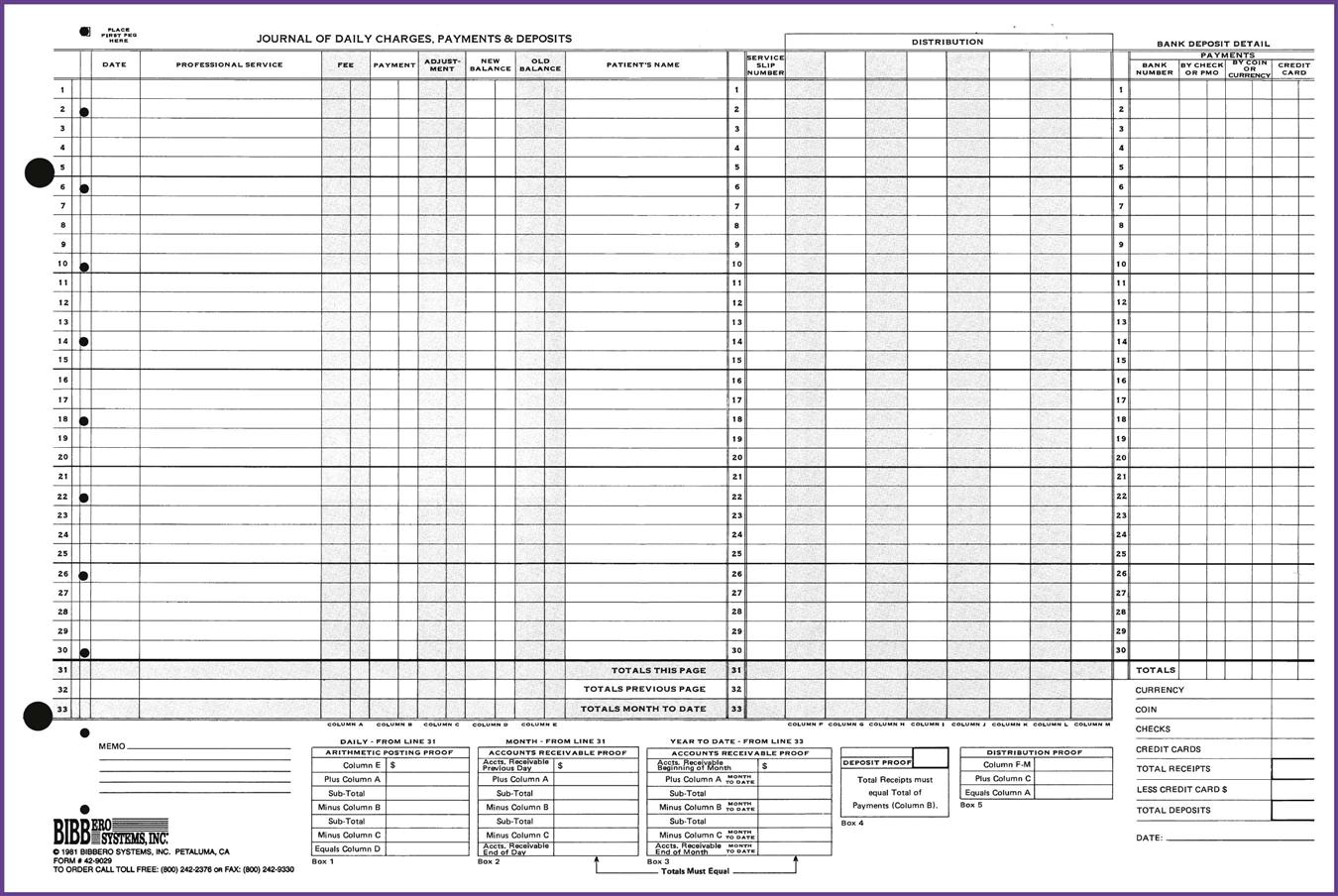

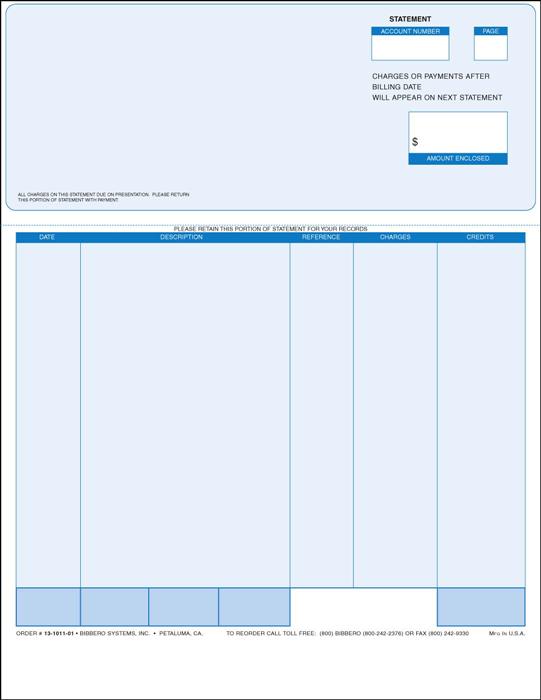

1. Define, spell, and pronounce the terms listed in the vocabulary. 2. List three values that are considered in determining professional fees. 3. Differentiate the terms usual, customary, and reasonable. 4. Discuss the value of fee estimates for patient treatment. 5. Explain basic bookkeeping computations. 6. Differentiate between bookkeeping and accounting. 7. Compare the manual and computerized bookkeeping systems used in ambulatory healthcare. 8. Identify procedures for preparing patient accounts. 9. Discuss the types of adjustments that may be made to a patient’s account. 10. Explain both billing and payment options. account A statement of transactions during a fiscal period and the resulting balance. account balance The amount owed on an account. accounts receivable ledger A record of the charges and payments posted on an account. decedent a person who is deceased. disbursements Funds paid out. fee profile A compilation or average of physician fees over a given period. fee schedule A compilation of pre-established fee allowances for given services or procedures. instigate To goad or urge forward; to provoke. intangible not made of physical substance; not able to be held or touched. medically indigent Able to take care of ordinary living expenses but unable to afford medical care. payables Balances due to a creditor on an account. preponderance A superiority or excess in number or quantity; a majority. professional courtesy Reduction or absence of fees to professional associates. receipts Amounts paid on patient accounts. receivables Total monies received on accounts. transaction An exchange or transfer of goods, services, or funds. unsecured A debt that is not protected by collateral. Jodie Bimmell, a registered medical assistant (RMA), has worked for Dr. Ted Crawford, an endocrinologist, for 3 years. She began as a receptionist, but she is proficient in mathematics and enjoys working with numbers. Because of Dr. Crawford’s confidence in her abilities, he placed her in charge of the accounting functions for the practice 2 years ago. When patients are ready to leave, Jodie totals their bill and enters the charges and payments into the computerized billing system, which also allows her to schedule return appointments. Because Jodie also has learned quite a bit about medical insurance, she can answer most of the patients’ questions about their coverage and the benefits or exclusions of their policies. She knows where to direct patients who have more complicated questions and how to follow up to ensure that they received an answer—one of the most important duties of a professional medical assistant. Jodie is able to decipher confusing explanations of benefits (EOBs) from insurance carriers and explain reimbursements to the patients. She has a great attitude about assisting patients with insurance questions and does not hesitate to call the insurance company or third-party payer on the patient’s behalf. She provides patients with exceptional customer service. Jodie knows to be careful when dealing with numeric transactions. Her handwriting is neat and legible, and she writes numbers the same way each time to prevent confusion and errors. She can work with a manual pegboard system in a pinch, but she uses the computerized billing system on a day-to-day basis. Jodie has some accounting background, which enables her to find errors easily and correct them. She is responsible for making sure the accounts balance on a daily, weekly, and monthly basis and considers errors a puzzle to solve and an opportunity to learn. She has never encountered an error she was unable to resolve by the end of the day. Jodie provides a valuable service to Dr. Crawford’s patients. She can be counted on to follow up on any detail that needs attention. When patients call her for assistance, she responds within 24 hours (often within 1 hour) with answers to their questions or a resource to help them. Jodie is willing to help any staff member with other duties when necessary and prides herself on being a patient advocate. She is an enthusiastic team player who puts the patients first. While studying this chapter, think about the following questions: The practice of medicine is both a business and a profession, and the details of conducting the business aspects of the practice often are the responsibility of the medical assistant. Although service to the patient is the primary concern of the medical profession, a physician must charge and collect a fee for such services to continue providing medical care to patients. Many factors contribute to the determination of fees for the services and treatment rendered to the patient. The medical assistant is responsible for informing the patient about financial matters, for billing insurance companies or other third-party payers, and in some cases for making payment arrangements. Setting fees is no simple matter. The physician has three commodities or values to sell: time, judgment, and services. Yet the value of these commodities is never exactly the same to any two individuals. Medical care has little value except to the patient receiving the care, and the value may not be consistent with the person’s ability to pay. In every case, the physician must place an estimate on the value of the services. This estimated figure is known as the physician’s fee for service. The value may then be modified by other considerations, such as an excessive length of time spent with the patient or an especially complicated group of illnesses suffered by one patient. The preponderance of patients enrolled in health maintenance organizations (HMOs) and preferred provider organizations (PPOs) is an important consideration for the physician. Under managed care contracts, the physician agrees to accept predetermined fees for specific procedures and services instead of the fee-for-service method. The patient may have to make a co-payment, which is determined by the insurance contract and is collected at the time of service. A base capitation plan pays the provider a set amount for each patient enrolled in a group, and this amount is meant to cover all the patient’s healthcare expenses in a given period. However, if one or two people in the group become very ill, the physician may actually lose money, because those patients may use all the groups’ pooled money for that period. The economic level of the community plays a significant role in determining a physician’s fees. Different communities have multiple cost-of-living scales, and this affects medical fees. The prevailing rate in the community must be taken into consideration by each physician. Interestingly, fees that are too low drive patients away just as quickly as fees that are too high, because the average person tends to judge the worth of a product by its cost, and low cost can be translated as low value. Most insurance plans base their payments on a usual, customary, and reasonable (UCR) fee for a particular procedure. For example, suppose Dr. Crawford’s usual fee for new patients is $100. The customary charge for a first visit by other physicians in the same community with similar training and experience ranges from $75 to $125. Dr. Crawford’s fee of $100 is within the customary range and would be paid by an insurance plan that pays on a usual and customary basis. However, if the range of usual fees in the community is $60 to $85, the insurance plan would allow only the maximum within the range, or $85. If Dr. Crawford spent 2 hours on a lengthy history and physical examination for a patient with a terminal illness, his charge of $175 might be considered reasonable, as long as he had documentation in the patient’s chart to justify the charges. The Evaluation and Management (E/M) section of procedural coding manuals is carefully written to allow physicians to indicate the appropriate level, or extent, of the patient history, physical examination, and complexity of medical decision making. The physician does not act alone in determining fees. A third-party payer may provide a schedule of predetermined fees. Some require preapproval of the fee before service is rendered, and some require precertification before paying for certain services. Government programs, such as Medicare and Medicaid, have strict guidelines for reimbursement. The physician may have to adjust part of the fees to meet contractual obligations with the third-party payer. The fiscal agent (or fiscal intermediary) for government-sponsored insurance programs and some private plans keeps a continuous record of the usual charges submitted for specific services by each physician. When these fees have been compiled and averaged over a given period, usually a year, the physician’s fee profile is established. The fee profile is used in determining the amount of third-party liability for services under the program. Physicians often object to the lag between a private fee increase and the point when it is reflected in payments by an insurance carrier. This interval can be as long as 2 to 3 years. In some individual cases, the physician may not want to charge the patient more than the person’s insurance allows. This sometimes is a professional courtesy (which may be extended to healthcare professionals); in other cases, it is applied as the physician sees fit. Always charge the full fee first, with the understanding that after the insurance allowance has been received, the balance may be discounted or adjusted. If a smaller fee is quoted and charged at a discount, several things can happen: Patients, especially new ones, naturally wonder how much their office visits and treatments will cost, but they often are reluctant to voice their concern. The first step in discussing financial issues is to make sure the conversation is held out of the hearing range of other patients. If the discussion is to be held during the checkout process, make sure this is done in a private area or that other patients are out of earshot. Patients are hesitant to discuss financial issues with strangers lingering. Do not wait for the patient to ask about fees. The physician or the medical assistant should approach the subject if the patient does not do so. Be prepared to discuss costs with all patients and ask whether they have questions about the fees. The medical assistant might open the conversation by saying, “Mr. Conn, do you have any questions about the costs of your operation? If you do, I’ll be glad to review them with you.” Never sidestep payment issues by saying, “Don’t worry about the bill; let’s just get you well first.” The patient may later complain about the bill because he or she misunderstood the complexity of the service. Even when the physician quotes a fee, the medical assistant often is responsible for explaining the physician’s fees to the patient. Know how fees are determined and why charges vary. Develop a thorough knowledge of the physician’s practice and policies so that handling perplexing situations involving fees becomes routine. Educate patients that the money spent for medical care is an excellent investment in the future. It is the rare patient who understands the intricate procedures involved in diagnosis and treatment, especially when third-party payers are involved, so be patient and understanding when questions arise about fees. Explain that compliance with the physician’s orders may actually save the patient money over time. Each patient should control and manage his or her current diseases and prevent symptoms from worsening or new disorders from developing; this ultimately reduces the patient’s healthcare costs. Patients can better plan for medical expenses when fees are discussed before treatment. Most patients want to meet their financial obligations but rightfully insist on an accurate estimate of those costs before they commit to paying them. Misconceptions and complaints about overcharging and fee discrepancies often are eliminated when fees are explained to the patient before a procedure or surgery is scheduled, even to the point of describing how a fee is established. Some physicians offer a discount if a patient has no insurance and pays cash. Although some physicians will allow fee negotiation in special circumstances, most managed care contracts require the physician to charge the correct co-payment and do not allow further discounts. When discussing patients’ fees, remember to explain additional costs that extend beyond the physician’s own charges. For example, if a patient is to undergo surgery, the person should know the costs of the operation, the anesthesiologist’s and radiologist’s charges, the laboratory fees, and the approximate hospital bill. If consultation becomes necessary, inform the patient that a separate bill will be sent by the consulting physician and that the consultation is for the benefit of the patient and the referring physician. Most physicians give patients an estimate of medical expenses before hospitalization; these estimates often are developed in cooperation with local hospitals or surgery centers. Individual physicians occasionally work up their own estimate forms while in the treatment room with the patient. Patients must usually budget their money for medical procedures, and most physicians are willing to work with the patient to make payment arrangements, especially for expensive treatments or procedures, or when responding to emergency situations. Estimates also are helpful when the patient is faced with long-term treatment. Always emphasize that the information is only an estimate and that the actual cost may vary somewhat. Estimate slips should be prepared in duplicate so that the patient has a copy. Retain the original in the patient’s medical record. Using estimates (1) documents that a fee was quoted; (2) helps to eliminate the possibility of misquoting the fee later; and (3) simplifies collections by clarifying expected payments, which prevent misunderstanding and confusion over charges. Patients must understand that the guarantor is the person ultimately responsible for the entire bill. The insurance policy is a contract between the policyholder or between a group of people (e.g., an employer) and an insurance company or managed care organization. The physician is not a party to this contract. Therefore, physicians and their staff are not responsible for pursuing insurance payment for the benefit of the patient. However, it is in the best interest of the staff to actively assist the patient if problems occur securing payment. This is true for two reasons. First, the staff is almost always more knowledgeable about the insurance business than the patient. Many patients do not even read their insurance policies and have no idea what is and is not covered. Some patients expect insurance to pay all costs simply because they are paying a high premium or payment. The medical assistant may need to educate these patients about their policies and offer advice on how patients can effectively work with the insurance company to get answers to questions and make sure they are receiving all the benefits to which they are entitled. Second, helping the patient secure payment means that the physician will be compensated for his or her services. If the medical assistant acts as a patient advocate with the insurance company, these efforts usually result in payment of the contracted amount of the bill. Make sure the proper co-payments are received and credited to patients’ accounts. Medical assistants gain knowledge about the insurance industry when they actively assist patients with their concerns. The more experience a medical assistant has in working with insurance and third-party payers, the more helpful he or she can be to patients. The medical assistant should keep a notebook with specific information about each type of policy the office handles; this will be a source of excellent guidance and suggestions when working with a particular payer. Always be sure to secure guarantors in writing. Most patient information sheets have a section referring to the guarantor. A statement may be included that the guarantor signs, indicating an agreement to pay the costs of medical care. States have varying statutes that deal with guarantors, so be sure the office’s policies reflect compliance with those laws. It is especially important to secure a written agreement to pay for services when the care will be long term or when a costly treatment or surgical procedure must be done. The slips attached to charts while the patient is in the office are called encounter forms (Figure 22-1; additional examples of encounter forms are available on the Evolve Web site). The encounter form provides information about the patient, such as the name, account number, and previous balance. Current charges and payments for the visit are added after the physician sees the patient. The physician can indicate on the encounter form when the patient should return to the clinic. The medical assistant then schedules a return appointment and can even use the patient’s copy of the encounter form to note the next appointment date and time. The encounter form normally consists of three parts: a white top sheet, a yellow sheet, and a pink sheet. The colors can vary, but the white copy usually is kept as a permanent record by the office, and the yellow and pink copies are given to the patient. The patient uses the yellow copy for insurance billing (if it is not done by the office), and the pink copy is a receipt for the patient. Encounter forms sometimes are designed to work with a pegboard system, or they may be available in continuous forms that can be placed in the printer for computer use. Encounter forms have been known by many other names throughout the years, including superbills, charge slips, and multipurpose billing forms. Modern computer systems allow receipts to be printed directly from the computer. A business transaction is the occurrence of an event or of a condition that must be recorded. For example, when a service is performed for which a charge is made, when a debtor makes a payment on an account, when a piece of equipment is purchased, or when the monthly rent is paid, a business transaction has been completed. Each of these examples is a transaction that must be recorded in the accounting system. Medical assistants need to understand the difference between bookkeeping and accounting. Accounting is a four-stage process of recording, classifying, summarizing, and interpreting financial statements. The physician may have an accountant who provides periodic summaries and handles tax planning and payment for the physician. Bookkeeping is the recording stage of accounting. The medical assistant performs bookkeeping functions when posting a payment to a patient’s account. A patient’s financial record is called an account. All of the patients’ accounts together (in the entire practice) constitute the accounts receivable ledger. Account (or ledger) cards vary in design (Figure 22-2), but all have at least three columns for entering figures: An adjustment column is available in some systems and is used to enter professional discounts, write-offs, disallowances by insurance companies, and any other adjustments. In a computer system, when a patient is called up by name or identification number, the patient’s balance appears. This is the individual patient’s ledger. Posting is the transfer of information from one record to another. Transactions are posted from the journal to the ledger; this is accomplished in one writing on the pegboard system. The account balance normally is a debit balance, which means that the charges exceed the payments on the account. A debit balance is entered simply by writing the correct figure in the balance column. A credit balance exists when payments exceed charges (e.g., when a patient pays in advance). This is common in obstetric practices. If a payment is made, that amount is entered and subtracted from the charge to arrive at the patient’s account balance. If the patient or the patient’s insurance company pays more than the charge, the patient has a credit balance. Occasionally, an adjustment may be made to the patient’s account; for instance, if the insurance company pays only $80 of a $100 charge, the physician may adjust $20 from the patient’s account, especially if the physician is contracted to accept the allowed amount. Discounts are also credit entries and are entered in the adjustment column; if there is no such column, the discount is entered in the debit column and enclosed in parentheses. When the entry is made this way, it is recognized as a subtraction from the charges. When columns are totaled, any figure in red or in parentheses is always subtracted. Receipts are cash and checks taken in payment for professional services. Receivables are charges for which payment has not been received; that is, amounts owed. Disbursements are cash amounts paid out. Payables are amounts owed to others but not yet paid. All charges and payments for professional services are posted to the patient’s account card or record daily. The record then becomes a reliable source of information for answering all inquiries from patients about their accounts. A separate account card or record is prepared for each patient at the time of the first visit or service. The record should include all information pertinent to collecting the account, such as: Billing statements to the patient and the patient’s insurance carrier are prepared from the record. The patient’s name, date, and diagnosis and the procedures performed are posted when the patient is leaving the office. Computerized bookkeeping systems for medical offices vary in cost and capability. A computerized system reduces the time needed to balance the day sheet and the totals for monthly and year-to-date balances (Procedure 22-1). The software for these programs may need to be updated periodically. Several staff members can access the information in the computer at the same time, and output is legible over the long term compared to some handwritten information. Because computers are multiuse devices, several types of software programs can be housed on one computer. Manual systems are designed to do one thing and cannot provide information other than what has been posted on the system by hand. Although most physicians have converted to an electronic billing system, some still use the pegboard for a number of reasons. Many rural physicians, those in practice for many years, and those that run small practices believe that conversion to an electronic system would not be worth the high cost involved in implementation. Although it is certainly the physician’s choice as to the system the office uses, electronic medical records are more efficient. Nonetheless, the medical assistant benefits by learning how the manual pegboard system works. The bookkeeping concepts taught in using a manual system help the student understand the way a computerized system works. Whether manual or electronic, the physician’s billing system must be accurate and cost effective and must allow quick retrieval of information. Although we live in a technology-savvy world, there are many physicians who still use manual pegboard systems. Often, physicians who have been in practice for many years do not want to invest in a computerized billing system, because they may not plan to be in practice long enough to justify the cost. Usually, these doctors also still use a manual, written charting system. Additionally, some certifying exams still contain questions about manual systems. If the office experiences a power outage, the employees will have to use a manual system for the period in which patients are seen while the power is out. The medical assistant needs to be familiar with both manual and computerized bookkeeping systems. The pegboard is the most popular manual system for this purpose. The initial cost of materials for the pegboard system is slightly more than that for other manual accounting systems but is still less than the cost of most billing management computer software systems. The pegboard is simple to operate, and once a medical assistant learns the pegboard system, computer systems are much easier to understand. The system gets its name from the lightweight aluminum or Masonite board that is used. This board has a row of pegs along the side or top that holds the forms in place. The accounting forms are perforated for alignment on the pegs. All the forms used in any system must be compatible so that they can be aligned perfectly on the board. The pegboard system generates all the necessary financial records for each transaction in one writing, as follows: The system also may include a statement and bank deposit slip. It provides current accounts receivable totals and a daily record of bank deposits and cash on hand, in addition to the record of income and expenses. The need for separate posting to patient accounts is eliminated, and the chance for error is reduced. The pegboard system allows the medical assistant to keep control over cash, collections, and receivables and ensures that every cent is accounted for and properly entered. It provides a record of every patient, every charge, and every payment, plus a daily recap of earnings—a running record of receivables and an audited summary of cash—and requires little time. If the medical facility uses a computerized billing system, turn on the computer and open the accounting software. Some advanced systems allow patients to check in at a computer in the reception area. When such a system is used, the patient must be taught how to enter his or her information. Once the patient has seen the physician and is ready to leave the office, he or she brings the encounter form to the checkout area. The medical assistant reviews the encounter form for the charges noted by the physician, and those charges are entered into the computer. Payments are noted after the charges have been entered. Make sure the system has a reliable backup so that the patient account information is not lost. Back up the system daily to prevent the loss of all or part of patients’ account information. If a pegboard system is used, place a new day sheet on the board daily, even if there is still room left on the previous day sheet. This is helpful if a specific transaction needs to be looked up. The medical assistant can refer to a specific day sheet, rather than scan through several sheets, if he or she knows the date of the transaction. Most systems use no carbon required (NCR) paper on both encounter forms and account cards. If the encounter forms are shingled, lay the entire bank of receipts over the pegs, with the top one aligned with the first open writing line on the day sheet. The account card is placed underneath the encounter form but on top of the day sheet. Therefore, when the entry is recorded, the medical assistant writes on the encounter form, and the entry shows on the account card and the day sheet. Encounter forms should be used in numeric order. Save time by pulling account cards for all scheduled patients during morning preparation time. When a computerized billing system is used, charges are entered into the computer at the end of the visit and payment is collected from the patient unless other arrangements have been made. The encounter form is referenced at the end of the visit. When a pegboard system is used, transactions are initiated before the patient goes to the exam room. The patient’s ledger card is inserted under the first or next available receipt, with the first available writing line of the card aligned with the carbonized strip on the receipt. Enter the receipt number and date, the account balance in the space labeled previous balance, and the patient’s name. The information recorded on the receipt is posted automatically to the ledger and the day sheet. The charge slip then is detached and clipped to the patient’s chart to be routed to the physician. After the service has been performed, the physician enters it on the encounter form and the patient or the nurse returns it to the medical assistant at the checkout desk. Charges are coded in the computerized billing system, and the computer also generates billing forms for insurance purposes. Whether a computerized or manual system is used, the charges posted to the patient’s account should be taken from the physician’s fee schedule. Computerized systems can automatically display the fees when a certain procedure code is entered. When checking out a patient using a pegboard system, the medical assistant should insert the ledger card under the proper receipt and check the number previously entered to make sure the correct card is being used. Record the service by procedure code, post the charge from the fee schedule, enter any payment made, and write in the current balance (Procedure 22-2). If there is no balance, place a zero or a straight line in the balance column. The transaction has now been posted to the journal and the account, and if payment was made by the patient, a receipt has been generated. The service receipt is given to the patient; no other receipt is necessary. The account card is ready for refiling. File the encounter forms in numeric order for any internal audit. At the end of the month, the total of the encounter forms should equal the total of the charges recorded on the day sheets for the month (Figure 22-3). Payments may be received in the mail or may be brought in by patients some time after a service was performed. With a computer system, payments are simply entered into the computer and credited to the patient’s account. With a manual system, payments are entered on the day sheet and the account card as described previously. Payments sent by mail do not require a receipt unless the patient specifically requests one. The physician may have daily charges for visits to patients in a hospital or convalescent facility. Enter these charges on the day sheet and ledger card only. Surgery fees usually are recorded as one entry that includes the surgery and aftercare. All these charges are easily entered into a computer billing system.

Professional Fees, Billing, and Collecting

Learning Objectives

Vocabulary

Scenario

How Fees are Determined

Impact of Managed Care

Prevailing Rate in the Community

Usual, Customary, and Reasonable Fees

Fee Setting by Third-Party Payers

Physician’s Fee Profile

Insurance Allowance

Explaining Fees to Patients

Discussion of Fees in Advance

Explanation of Additional Fees

Fee Estimates

The Guarantor’s Ultimate Responsibility

Charging the Patient for Medical Services and Procedures

Computations Used on Patient Accounts

Comparison of Manual and Computerized Bookkeeping Systems

Computerized Bookkeeping Systems

Manual Bookkeeping Systems

Preparing Patient Accounts for Daily Transactions

Entering and Posting Transactions

Posting Other Payments and Charges

Professional Fees, Billing, and Collecting

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access