Procedural, Evaluation and Management, and HCPCS Coding

Chapter objectives

After completion of this chapter, the student should be able to:

1. Discuss the purpose and development of the CPT-4 manual.

2. Name and describe the three levels of procedural coding.

3. Explain the format of Current Procedural Terminology (CPT).

4. Interpret the conventions and punctuation used in CPT.

5. List the basic steps in CPT coding.

6. Outline the important rules and regulations for Evaluation and Management (E & M) coding.

7. Discuss the subheadings of the main E & M section.

8. Explain the use of E & M modifiers.

9. List the general principles of medical record documentation.

10. Provide an overview of the HCFA Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS).

11. Explain the rationale of the National Correct Coding Initiative (NCCI).

Chapter terms

adjudication

category

Category II codes

Category III codes

code set

concurrent care

consultation

counseling

CPT-5

critical care

crosswalk

emergency care

established patient

Evaluation and Management (E & M) codes

face-to-face time

HCFA Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS)

HCPCS codes

Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA)

indented codes

inpatient

key components

Level I codes

Level II codes

Level III codes

main terms

modifiers

modifying terms

new patient

observation

outpatient

Physicians’ Current Procedural Terminology, 4th Edition (CPT-4)

referral

section

see

special report

stand-alone code

subheading

subjective information

subsection

unit/floor time

Overview of current procedural terminology (CPT) coding

The Physicians’ Current Procedural Terminology, 4th Edition (CPT-4), is a manual containing a list of descriptive terms and identifying codes used in reporting medical services and procedures performed and supplies used by physicians and other professional healthcare providers in the care and treatment of patients. Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) was first developed and published by the American Medical Association (AMA) in 1966. The CPT system is governed by the CPT editorial panel, a group of individuals (made up mostly of physicians representing various specialties of medicine) who have the authority to make final decisions regarding changes and updates with regard to the content of CPT.

Because medicine is constantly changing, the AMA publishes an updated version of the CPT manual every year. It is important that the health insurance professional use the most recent edition of CPT when coding professional procedures and services for claims submissions to avoid rejected claims or incorrect claim adjudication (the process of deciding how an insurance claim is paid).

In 1983, CPT was adopted as part of the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS). With this adoption, HCFA (now called the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS]) mandated the use of HCPCS (pronounced “hick picks”) to report services for Part B of the Medicare Program. In October 1986, HCFA also required state Medicaid agencies to use HCPCS in the Medicaid Management Information System. In July 1987, as part of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act, HCFA required the use of CPT for reporting outpatient hospital surgical procedures. Today, in addition to use in federal programs (Medicare and Medicaid), CPT is used extensively throughout the United States as the preferred system of coding and describing healthcare services.

In 2000, the CPT code set was designed by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services as the national coding standard for physicians and other healthcare providers to report professional services and procedures under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). The CPT code set must be used for all financial and administrative healthcare transactions that are transmitted electronically.

Today, not only Medicare and Medicaid but also most managed care and other insurance companies base their reimbursements on the values established by the CMS. As with ICD-10-CM diagnostic coding, it is important that the health insurance professional have a thorough understanding of CPT coding to facilitate accurate claims completion for maximal reimbursement. CPT codes are used instead of a narrative description in claim submission to describe what services or procedures were provided or what supplies were used during the patient encounter.

Purpose of CPT

The purpose of CPT coding is to provide a uniform language that accurately describes medical, surgical, and diagnostic services, serving as an effective means for reliable nationwide communication among physicians, insurance carriers, and patients. CPT codes are also used by most third-party payers and government agencies as a record of the activities of an individual healthcare provider.

Development of CPT

As mentioned previously, the AMA developed and published the first CPT in 1966. This first edition contained primarily surgical procedures with limited sections on medicine, radiology, and laboratory procedures.

The second edition was published in 1970 and presented an expanded system of terms and codes to designate diagnostic and therapeutic procedures in surgery, medicine, and other specialties. At that time, the 5-digit coding system was introduced, replacing the former 4-digit classification. Another significant change was a listing of procedures relating to internal medicine.

The third and fourth editions of CPT were introduced later in the 1970s. The fourth edition, published in 1977, presented significant updates in medical technology. Also, a system of periodic updating was introduced to keep pace with the rapidly changing medical environment.

Three levels of procedural coding

HCFA Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes are descriptive terms with letters or numbers or both used to report medical services and procedures for reimbursement. As discussed earlier, the codes provide a uniform language to describe medical, surgical, and diagnostic services. HCPCS codes are used to report procedures and services to government and private health insurance programs, and reimbursement is based on the codes reported. A code, in place of a narrative description, can summarize the services or supplies provided when billing a third-party payer. HCPCS codes are grouped into three levels, as follows:

CPT manual format

Introduction and Main Sections

Similar to the ICD-10-CM manual, CPT-4 is made up of several sections beginning with an introduction, identified by lowercase Roman numerals. The main body of the manual follows the introduction and is organized in six sections. Within each section are subsections with anatomical, procedural, condition, or descriptor subheadings. Table 13-1 lists the CPT sections and their number range sequence. The listed procedures and services and their identifying 5-digit codes are presented in numerical order except for the E & M section. Because E & M codes are used by most physicians for reporting key categories of their services, this section is presented first.

Table 13-1

CPT Section Numbers and Their Sequence

| Section Title | Numbering Sequence |

| Evaluation and Management | 99201-99499 |

| Anesthesiology | 00100-01999, 99100-99140 |

| Surgery | 10021-69990 |

| Radiology (including Nuclear Medicine and Diagnostic Ultrasound) | 70010-79999 |

| Pathology and Laboratory | 80047-89398 |

| Medicine (except Anesthesiology) | 90281-99199, 99500-99607 |

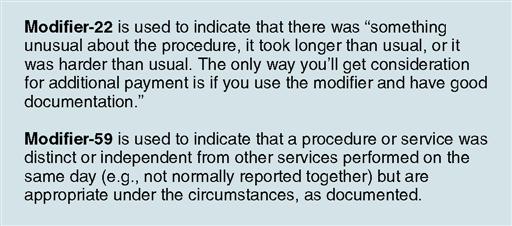

Five-digit CPT codes may be defined further by modifiers to help explain an unusual circumstance associated with a service or procedure. Appropriate coding modifiers are crucial to getting claims paid promptly and for the correct amount. Missing or incorrect modifiers are among the most common reasons that claims are denied by payers. It is easy to get confused on how to use modifiers correctly, especially because, similar to CPT codes, they are constantly changing. The most important thing to remember when using modifiers is that the health record must contain adequate documentation to support the modifier (Fig. 13-1). Modifiers are discussed in more detail on page 278.

When coding procedures, it is important always to have the most recent edition of the CPT book available to look up current modifier codes. (Modifiers are listed in Appendix A at the back of the CPT manual.) Also, it is advisable for healthcare providers and their billing staff to read Medicare (and other) coding newsletters and attend coding workshops periodically to keep up to date.

Each main section of the CPT is preceded by guidelines specific to that section. These guidelines define terms that are necessary to interpret correctly and report the procedures and services contained in that section. The health insurance professional should read and study these guidelines before attempting to assign a code.

Category II Codes

Category II codes are supplemental tracking codes, intended to be used for performance measurement. Category II codes provide a method for reporting performance measures. They are intended to facilitate the collection of information about the quality of care delivered by coding numerous services or test results that support performance measures that have been agreed on as contributing to good patient care. Category II codes are alphanumeric, consisting of 4 digits followed by the letter “F” (e.g., 0503 F—Postpartum care visit [Prenatal]). The use of Category II codes is optional, and they should not to be used as a substitute for Category I codes. Category II codes follow the six sections listed in the main body of the CPT manual.

Category III Codes

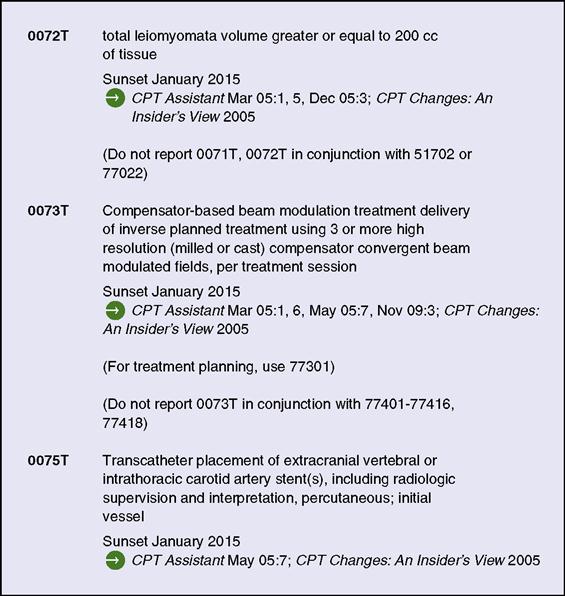

Immediately following the Category II codes are the Category III codes (Fig. 13-2). Category III codes were established by the AMA as a set of temporary CPT codes for emerging technologies, services, and procedures for which data collection is necessary to substantiate widespread use or for the approval process of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). To be eligible for a Category III code, the procedure or service must be involved in ongoing or planned research. If a Category III code has not been proposed and accepted into the main body of CPT (i.e., Category I codes) within 5 years, it is archived, unless a demonstrated need for it develops.

In the introduction of the CPT manual, users are instructed not to select a code that merely approximates the service provided. The code should identify the service performed accurately. In some instances, Category III codes may replace temporary local codes (HCPCS Level III) assigned by carriers and intermediaries to describe new procedures or services. If a Category III code is available, it must be used instead of an unlisted Category I code. The use of the unlisted code does not offer the opportunity for collection of specific data. Category III codes are updated semiannually in January and July, and new codes are posted on the AMA website.

Appendices A through N

As with ICD-10-CM, CPT-4 contains several appendices, which follow the Category III codes. These appendices and their contents are as follows:

Appendix A—Modifiers

Appendix B—Summary of Additions, Deletions, and Revisions

Appendix C—Clinical Examples

Appendix D—Summary of CPT Add-On Codes

Appendix E—Summary of CPT Codes Exempt from Modifier -51

Appendix F—Summary of CPT Codes Exempt from Modifier -63

Appendix G—Summary of CPS Codes That Include Moderate (Conscious) Sedation

Appendix H—Alphabetic Index of Performance Measure by Clinical Condition by Topic

Appendix I—Genetic Testing Code Modifiers

Appendix J—Electrodiagnostic Medicine Listing of Sensory, Motor, and Mixed Nerves

Appendix K—Products Pending FDA Approval

Appendix M—Summary of Crosswalked Deleted CPT Codes

CPT Index

Main Terms

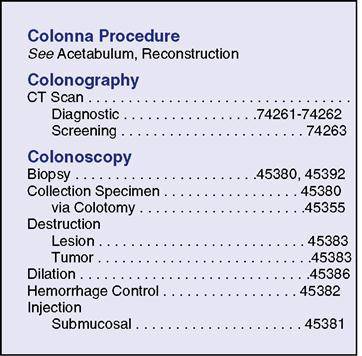

In the CPT manual, the index is presented last. As with ICD-10-CM, the CPT index is organized by main terms (Fig. 13-3). Each main term can stand alone, or it can be followed by up to three modifying terms. There are four primary classes of main term entries, as follows:

1. Procedure or service (e.g., colonoscopy, anastomosis, debridement)

2. Organ or other anatomical site (e.g., fibula, kidney, nails)

3. Condition (e.g., infection, pregnancy, tetralogy of Fallot)

4. Synonyms, eponyms, and abbreviations (e.g., ECS, Pean operation, Clagett procedure)

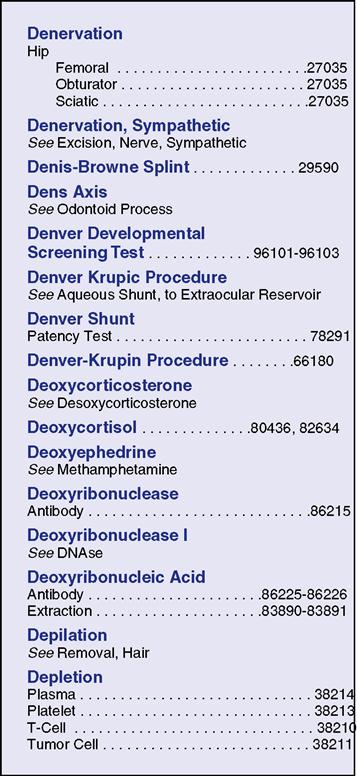

Modifying Terms

As mentioned previously, each main term can stand alone or be followed by up to three modifying terms (Fig. 13-4). Modifying terms are indented under the main term; in some cases, unindented anatomical sites are listed alphabetically first, and modifying terms are indented under them. For example, in Fig. 13-4, “Hip” is listed under the main term “Denervation” (in bold), after which three indented modifying terms are listed. All modifying terms should be examined closely, because these subterms often have an effect on the selection of the appropriate procedural code.

Code Layout

A CPT code can be displayed in one of the following three ways:

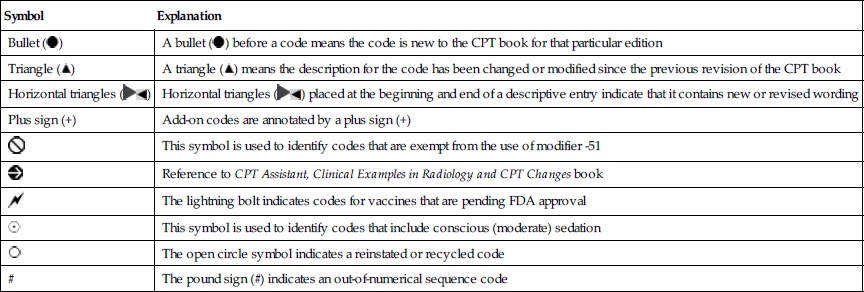

Symbols Used in CPT

The CPT manual uses several symbols that help guide the health insurance professional in locating the correct code. Accurate procedural coding cannot be accomplished without understanding the meaning of each of these symbols (Table 13-2). These symbols are listed on the inside front cover of the CPT manual.

Table 13-2

| Symbol | Explanation |

Bullet ( ) ) | A bullet ( ) before a code means the code is new to the CPT book for that particular edition ) before a code means the code is new to the CPT book for that particular edition |

Triangle ( ) ) | A triangle ( ) means the description for the code has been changed or modified since the previous revision of the CPT book ) means the description for the code has been changed or modified since the previous revision of the CPT book |

Horizontal triangles (  ) ) | Horizontal triangles (  ) placed at the beginning and end of a descriptive entry indicate that it contains new or revised wording ) placed at the beginning and end of a descriptive entry indicate that it contains new or revised wording |

| Plus sign (+) | Add-on codes are annotated by a plus sign (+) |

| This symbol is used to identify codes that are exempt from the use of modifier -51 | |

| Reference to CPT Assistant, Clinical Examples in Radiology and CPT Changes book | |

| The lightning bolt indicates codes for vaccines that are pending FDA approval | |

| This symbol is used to identify codes that include conscious (moderate) sedation |

| The open circle symbol indicates a reinstated or recycled code |

| # | The pound sign (#) indicates an out-of-numerical sequence code |

Modifiers

Modifiers are important to ensuring appropriate and timely payment. A health insurance professional who understands when and how to use modifiers reduces the problems caused by denials and expedites processing of claims.

A modifier provides the means by which the reporting healthcare provider can indicate that a service or procedure performed has been altered by some specific circumstance, but its definition or code has not been changed. The judicious application of modifiers tells the third-party payer that this case is unique. By using appropriate modifiers, the office may be paid for services that are ordinarily denied. In addition, modifiers can describe a situation that, without the modifier, could be considered inappropriate coding.

Modifiers are not universal; they cannot be used with all CPT codes. Some modifiers may be used only with E & M codes (e.g., modifier -24 or modifier -25), and others are used only with procedure codes (e.g., modifier -58 or modifier -79). Check the guidelines at the beginning of each section for a listing or description of the modifiers that may be used with the codes in that section. Appendix A of the CPT manual contains a list of modifiers and their use.

Unlisted Procedure or Service

Coders must understand the appropriate use of unlisted CPT codes. Unlisted codes are used for services that may be performed by physicians or other healthcare professionals that are not represented by a specific Category I (CPT) code. At the end of each subsection or subheading in question, a code is provided under the heading “other procedures,” which typically ends in “-99.” In the surgery section, note the “other procedures” code 39499 at the end of the “mediastinum” subsection. This code would be used for any unlisted procedures of the mediastinum.

Important note: Unlisted procedure codes should be assigned only if no other, more specific CPT code is available. If there is a Category III code that appropriately describes the procedure, it should be used instead of an unlisted code.

Special Reports

When a rarely used, unusual, variable, or new service or procedure is performed, many third-party payers require a special report to accompany the claim to help determine the appropriateness and medical necessity of the service or procedure. Items that should be addressed in the report, if applicable, include

• a definition or description of the service or procedure;

• the time, effort, and equipment needed;

• symptoms and final diagnosis;

• pertinent physical findings and size;

• diagnostic and therapeutic services;