Chapter 44 The preterm baby and the small baby

At the end of this chapter, you will have:

Introduction

Gestation

Low gestational age at birth is a principal factor associated with perinatal mortality. Babies born very preterm are at particular risk of sensory, cognitive and motor dysfunction (Cooke 2005, Marlowe et al 2005). Data are now available to monitor trends, and inform care for preterm births. In 2006 in England and Wales, 7.6% of live births were preterm, 88% were born at term, and 4% were born post term, with corresponding infant mortality rates of 41.0, 1.9, and 1.5 deaths per 1000 live births (ONS 2009). Almost two-thirds of all infant deaths occurred to babies born preterm. Infant mortality was highest at the very low gestational ages.

Antenatally, gestation is estimated from the date of the last menstrual period and the woman’s normal cycle, clinical examination and early ultrasound scan measurements and uterine growth (see Chs 32 and 33).

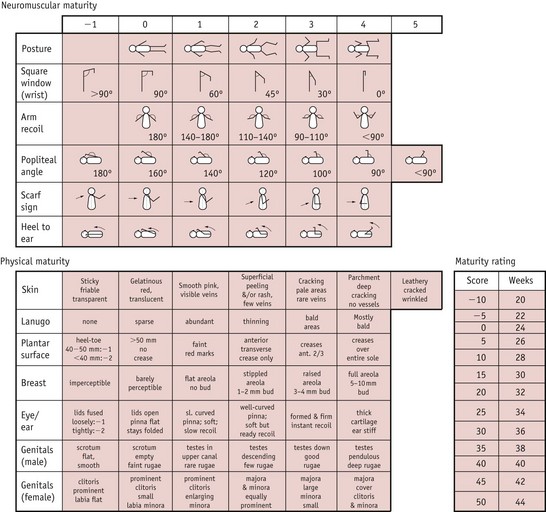

Scoring systems estimate the neonatal gestation following delivery and neonatal units will use one, or an adaptation of one or two of the common ones. Improved accuracy of antenatal ultrasound scans has led to less reliance on these scales. The Dubowitz scale (Dubowitz et al 1970) (see Fig. 44.1) is the most widely used in the UK, and providing the baby is well and examined within a few hours of delivery, is accurate to within 2 weeks. It involves scoring the baby on neurological states as well as external criteria but may be inappropriate for use with sick or ventilated neonates.

Figure 44.1 The Dubowitz score: graph for reading gestational age from total score.

(From Dubowitz et al 1970 with permission.)

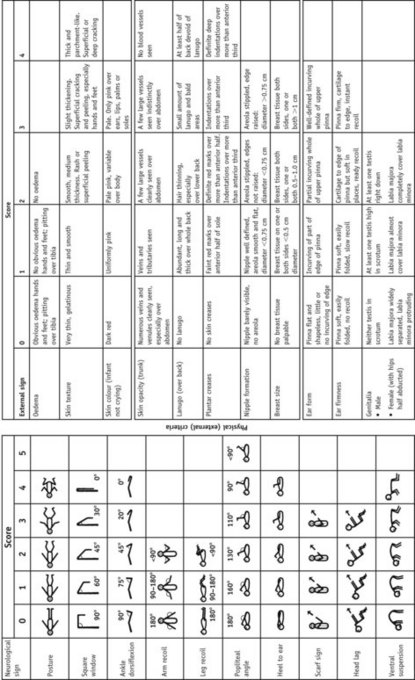

The Ballard score (an adaptation of the Dubowitz score) is a newer system (Fig. 44.2).

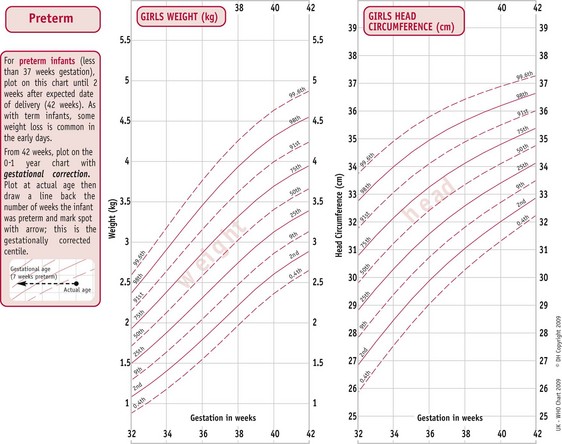

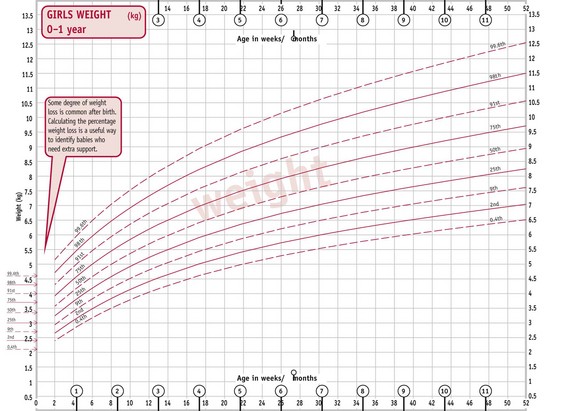

Centiles

Using an appropriate centile chart, the weight, head circumference and length of the baby is plotted against gestation and an assessment made of the growth. The centile chart forms an important part in providing a dynamic growth record and a link to the neonatal management (see Ch. 41).

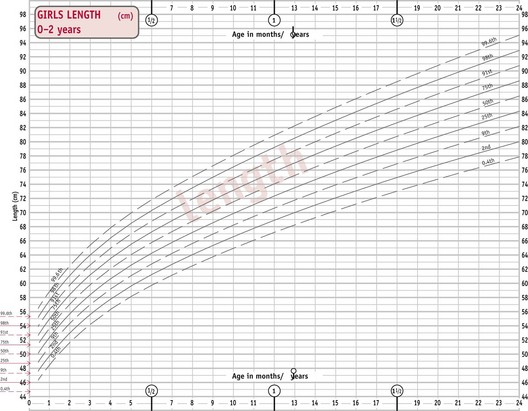

The UK World Health Organization (WHO) growth charts (2009) are based on measurements collected by the WHO in six different countries (Fig. 44.3) (see website). These describe optimal rather than average growth and set breastfeeding as the norm, illustrating how all healthy children are expected to grow.

(By kind permission of RCPCH/WHO/Department of Health 2009.)

C. Girls’ weight 0–1 year. D. Girls’ length 0–2 years.

(From http://www.rcpch.ac.uk/Research/UK-WHO-Growth-Charts, accessed 8/6/2010. Reproduced with permission.)

These classifications rely on accurate assessment of gestational age at delivery.

Birthweight

Babies may be grouped according to their birthweight – especially useful when the gestation is unknown. Many studies relate to birthweight rather than gestation as it is a better predictor of outcome. The WHO definition of low birthweight (WHO 1977) is internationally adopted, with further subdivisions as shown below:

Rapid recent developments in neonatology have resulted in the survival of LBW infants above 1500 g becoming commonplace.The distribution of births by gestational age varies considerably by birthweight. This has a signifiant effect on mortality and morbidity (ONS 2009) (see website).

The preterm baby

Causes

Infants born prematurely are at high risk of complications in the neonatal period and for later neurodevelopmental problems (Blackburn 2007). The causes of, and effective intervention strategies to prevent, preterm onset of labour have been researched. Specific events leading to onset of preterm labour and delivery are still uncertain and are likely to be a series or combination of maternal and fetal factors, or unexplained, rather than a single event, and include:

Characteristics (Fig. 44.4)

Labour and delivery

All resuscitation equipment must be checked and fully functional prior to the birth. An experienced paediatrician and midwife or neonatal nurse must be present at delivery to ensure immediate and expert resuscitation. Thermal care is vital at this point, as cold stress can increase mortality and morbidity in preterm infants (see Ch. 42). The radiant heater should be turned on prior to delivery. The room temperature should be increased to 26°C.

Infants over 30 weeks’ gestation should be dried thoroughly and wrapped in a warm towel, and a hat applied. Infants under 30 weeks’ gestation should not be dried but should have their bodies placed immediately in a plastic occlusive wrap. This should not be covered with a towel as the radiant heater needs to be directly above the baby (UK Resuscitation Council 2008). This allows visualization of the chest and ease of access whilst preventing evaporative heat loss and skin damage.

Common problems

Respiratory

The most common problems for preterm babies are respiratory disorders (discussed more fully in Chapter 45). The more preterm the baby, the more structurally and physiologically immature the respiratory system.

Apnoeas

Many preterm babies have apnoeas associated with their prematurity and require constant monitoring (Finer et al 2006). Parents need to understand the reasons for this, appreciating they resolve with maturity. Airway position is essential when nursing preterm infants, to reduce the potential for apnoeas caused by mechanical obstruction of the airway. Apnoea monitors should be removed several days prior to discharge so that parents gain confidence and do not become reliant on them. Caffeine is given as a stimulant until these apnoeas of prematurity resolve (Darnell et al 2006).

Oxygen therapy

Oxygen has been used more than any other drug in the treatment of preterm infants in the past 60 years. Oxygen therapy should provide adequate tissue oxygenation without creating oxygen toxicity. Excessive and fluctuating quantities is one factor in the aetiology of retinopathy of prematurity (Campbell 1951, Tin & Gupta 2007), though clinicians are still unsure how much oxygen these babies actually need, or how much is safe to give. Further major, multi-sited research is underway in Canada (see website).

Temperature control

At home, following an emergency or unexpected preterm birth, if no resuscitation is required, the midwife can place the baby on the mother’s abdomen or chest for skin-to-skin contact, once dried. The baby’s head should be covered with the mother and baby well wrapped in dry blankets. The aim is to maintain body temperature in the thermoneutral range, at which energy requirements are reduced to a minimum and oxygen consumption is less (see Ch. 42).

Hypoglycaemia

This is a common problem for preterm babies in the first 48–72 hours. Stores of brown fat, white fat and glycogen are too small to maintain blood sugar level when energy requirements are particularly high. Because of the heat loss from their large surface area, increased effort of breathing that accompanies respiratory difficulties, and greater rate of growth, more energy is expended for their weight than in their term counterparts. Asphyxia, sepsis, ischaemia and hypothermia all aggravate this. Preterm infants have immature liver function, with reduced availability of liver enzymes responsible for gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis, and are less able to produce alternative substrates, such as ketone bodies (Hume et al 2005).

Blood sugar levels should be checked every 4–6 hours during the first 48–72 hours after birth using a glucometer. Controversy still surrounds the clinical definition and significance of hypoglycaemia, but it is generally accepted that the neonatal brain can be damaged by hypoglycaemia, whether symptomatic or not (Schwarz et al 2003). Current recommendations are to maintain serum blood glucose levels above 2.6 mmol/L (Cornblath et al 2000).

Jaundice

Physiological jaundice is exacerbated in preterm babies as the liver is immature and therefore conjugation of bilirubin is further delayed (see Ch. 46).

Red blood cell lifespan is related to gestational age and may be only 35–50 days in the ELBW infant who may have ongoing low-grade haemolysis. Another contributing factor is the low levels of serum albumin in ELBW infants, which may limit extracellular binding and transport of bilirubin when concentrations are high (Cashore 2000).

Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA)

The ductus arteriosus fails to close in some very preterm and low-birthweight babies, partly because of immaturity and partly because the chemical conditions are not suitable in babies who are hypoxic and acidotic. Generally, in healthy preterm infants above 30 weeks’ gestation, the ductus arteriosus has closed functionally by 4 days. Only 11% of these infants have a PDA, compared to 65% of infants less than 30 weeks’ gestation with severe respiratory distress (Clyman 2004).

There are generally three physiological characteristics of a PDA in a preterm infant: