Chapter 22 Physical preparation for childbirth and beyond, and the role of physiotherapy

After reading this chapter and practising the suggested activities, you will:

Exercise and sport during pregnancy

Pregnancy is a time when women are often receptive to health education messages. This can include the introduction of exercise as not just having short-term benefits during the pregnancy and childbirth period, but also holding long-term health gains. There is evidence that exercise during pregnancy can benefit both the woman and fetus (RCOG 2006a) and is harmful to neither, provided the pregnant woman is progressing normally and healthily (Artal et al 2003). Therefore it is suggested that women should be encouraged to start, or continue with, appropriate exercise to derive the associated health benefits (NICE 2008, NICE 2010, RCOG 2006a). These include a reduction in fatigue, varicosities and peripheral swelling; a lower incidence of insomnia, stress, anxiety and depression; and, possibly, weight-bearing exercise in pregnancy may result in a shorter labour and a decrease in delivery-related complications (RCOG 2006a). In addition, a randomized study of women with gestational diabetes (Bung et al 1991) found that more than three-quarters of those following an exercise programme demonstrated improved glucose tolerance, so exercise is recommended for this group (RCOG 2006b). There is no robust evidence that exercise will prevent the onset of gestational diabetes in women (Artal & Sherman 1999).

It has been suggested that babies born to exercising women may tolerate labour better and be less likely to demonstrate signs of stress, such as meconium (RCOG 2006a).

There appears to be some variation between what are considered absolute or relative contraindications to (aerobic) exercise in pregnancy (ACOG 2002) and conditions requiring medical supervision while undertaking exercise in pregnancy (RCOG 2006a). Guidance produced by physiotherapists (ACPWH 2004) suggests the contraindications and precautions indicated in Table 22.1.

Table 22.1 Absolute contraindications and precautions to exercise in pregnancy*

| Absolute contraindication | Precaution |

|---|---|

| Serious cardiovascular, respiratory, renal or thyroid disease | Asthma |

| Poorly controlled type 1 diabetes | Diabetes type 1 if insulin regimens are well controlled and exercise is moderate – discuss with diabetic consultant, nurse or GP |

| Risk of, or current, premature labour | History of miscarriage |

| Cervical incompetence | Vaginal bleeding |

| History or risk of intrauterine growth retardation and premature labour – reduce activity after 12 weeks | Reduced fetal movement |

| Hypertension – should be discussed with the woman’s doctor | Pre-pregnancy hypertension |

| Placenta praevia after 26 weeks’ gestation – should be discussed with the woman’s doctor | Placenta praevia |

| Vaginal bleeding | |

| Hypertension – should be discussed with the woman’s doctor | Pre-pregnancy hypertension |

| Severe rhesus isoimmunisation | |

| Sudden swelling of ankles, hands or face | Anaemia |

| Acute infectious disease | |

| Extreme obesity | |

| Breech presentation | |

| Extreme underweight (BMI <12) | |

| Heavy smoking | |

| Thyroid disease |

The aim of exercise during pregnancy should be to maintain or moderately improve fitness levels (ACPWH 2004) without trying to reach peak fitness or train for competition (RCOG 2006a). It is impossible to go into any detail of different regimens within the constraints of this chapter, but the needs of different women will vary, based on whether they were a complete non-exerciser, non-regular exerciser, regular exerciser or elite athlete before conception (ACPWH 2004). Women should be advised to monitor their level of effort during exercise, to ensure that they are not overexerting themselves, and if using a gym, should seek advice from professional staff.

Commonly described tools are the talk test, Borg’s scale of perceived exertion, and heart rate (RCOG 2006a):

Women should avoid overheating during exercise, as a maternal core temperature over 39.2°C might be teratogenic in the first trimester (RCOG 2006a). They can minimize this risk by drinking sufficient fluids during exercise, and avoiding exercise in very hot conditions. Women must also know when to stop exercising, and seek a medical opinion. This includes onset of symptoms such as dizziness, faintness or headache; shortness of breath before exertion or breathlessness during exercise; any pain, e.g. abdomen, pelvic girdle; painful uterine contractions; decreased fetal movements; vaginal loss, urinary incontinence, ruptured membranes; swollen leg(s); muscle weakness (RCOG 2006b).

Those unaccustomed to exercise should be advised to start with 15 minutes of continuous exercise three times a week, gradually increasing to 30-minute sessions four times a week or daily (RCOG 2006a). Exercise in water, often referred to as aquanatal exercise, may offer a feeling of weightlessness, and reduced jarring of the joints, possibly offering some relief from aches and pains, an increase in energy and better sleeping (Brook et al 2008).

Scuba diving is contraindicated during pregnancy as the fetus is not protected against decompression sickness and gas embolism, and women should be warned that contact sports and pursuits which might result in a fall, such as horse riding, could result in fetal trauma (ACPWH 2004, RCOG 2006a).

Readers are advised to access appropriate sources – for example, ACPWH 2004, RCOG 2006a and 2006b – for further and updated evidence-based information, before discussing recreational exercise with pregnant women in their care.

Muscle groups

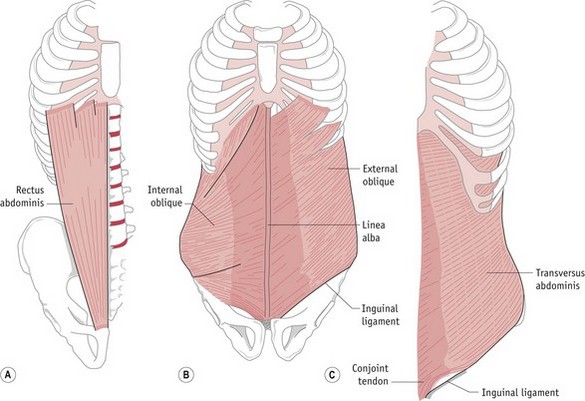

Two muscle groups that are affected more than others by pregnancy and childbirth because of their position, structure and function are those of the pelvic floor and abdominal wall. The pelvic floor is described and illustrated elsewhere within this book, but it is also useful to understand the structure and function of the abdominal muscles (Fig. 22.1).

The abdominal muscles have various roles, including protection and support for the abdominal contents. More specifically, their main functions are flexion of the lumbar spine (recti abdominis), side flexion and rotation of the spine (external and internal obliques) and postural support (transversus abdominis, working with the pelvic floor muscles) (Brook et al 2008). As pregnancy progresses, the abdominal muscles are stretched considerably by the gravid uterus, causing recti abdominis to become longer, wider and thinner (Y Coldron, unpublished PhD thesis, 2006). In addition, the linea alba (an area of connective tissue in the midline) may become wider and thinner (divarication) or even split (diastasis). Although there is little information on the effect of pregnancy on transversus abdominis (Brook et al 2008), its role along with the pelvic floor muscles – that is, support for the intra-abdominal organs, lower spine and pelvic girdle joints – is significant.

Pelvic floor muscle exercises

There is evidence that pelvic floor muscle exercises during pregnancy can prevent urinary incontinence (Mørkved et al 2003) and reduce the likelihood of prolonged second stage labour (Salvesen & Mørkved 2004). The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) has suggested that pelvic floor muscle training should be offered to women in their first pregnancy as a preventive strategy for urinary incontinence (NICE 2006a).

In non-pregnant women, research has suggested that a sizeable minority of women given verbal instructions on pelvic floor muscle exercises will not perform an optimum contraction (Bump et al 1991) and recent advice on the management of urinary incontinence suggests that a digital assessment of the muscles should be undertaken prior to commencing a course of exercises (NICE 2006a). Physiotherapists have been advised against such examination on pregnant women if there is a history of miscarriage or the woman has been advised to avoid sexual intercourse whilst pregnant (CSP 2003). Also, vaginal examination would not be practical in many situations when a pregnant woman is being advised on pelvic floor muscle exercises, e.g. parent education session, or exercise classes. Therefore, it is important that physiotherapists, midwives and any other health professionals teaching pelvic floor muscle exercises give clear instructions. There are many different ways to do this, including:

‘Imagine you are trying to stop yourself breaking wind, and at the same time trying to stop your flow of urine midstream’ (Brook et al 2008); the ‘lift’ analogy, i.e. closing the doors (a squeeze) and moving upstairs (a lift); the action of a vacuum cleaner (Bø & Mørkved 2007).

If women are not sure that they are contracting correctly, they could look at the perineum using a hand mirror, and see if the area lifts away from the mirror as they squeeze. Alternatively, they could try to stop the dribble at the end of voiding but should not stop midstream as this may disturb normal neurological activity (Bø & Mørkved 2007) and affect emptying.

Advice on how often to exercise and how many squeezes to undertake varies from author to author but a recent review of evidence suggests building up to 8–12 near-maximum contractions three times a day. In addition, any women experiencing stress or urge urinary incontinence should also squeeze before and during those activities which make them leak, e.g. cough, sneeze, on their way to the toilet (Bø 2007). A study of 23 pregnant women complaining of stress urinary incontinence (Miller et al 2008) showed they could reduce leakage by undertaking this anticipatory contraction, often referred to as ‘the Knack’.

Transversus abdominis exercises

‘Place your hand on the lower part of your tummy under your bump. Breathe in through your nose. As you breathe out, gently draw in your lower tummy away from your hand towards your back, then relax’ (ACPWH 2001).

As with pelvic floor muscle exercises, a review of the literature regarding exercise and pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain (Vleeming et al 2008

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree