Patient Assessment

Planned Procedure, Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Treatment Plan

Major Concerns of Patient and Family/Significant Others

Guidelines for Preoperative Education

Guidelines for Preoperative Education

Explanation of Planned Procedure

Importance of Peristomal Skin Management

Obtaining and Paying for Supplies

Attention to Sexual Concerns/Explanation of Potential Sexual Dysfunction

Basic Explanations Regarding Lifestyle Issues

Acknowledgment of Normal Stages of Adjustment

Determination of Need for Referrals

Considerations in Stoma Site Marking

Unique Stoma Marking Considerations

Evidence indicates that patients who receive preoperative ostomy education experience better recovery, possibly a shorter hospital stay, and fewer postoperative complications (Goldberg et al., 2010). Preoperative education can assist in alleviating the patients’ fears and anxieties associated with surgery and help them understand the adjustments that they will need to make for living with a stoma. The United Ostomy Associations of America’s (UOAA) Bill of Rights adopted in 1977 outlines 11 elements of care that should be the expectation of the person undergoing ostomy surgery (see Box 8-1). The elements include the right to have a preoperative counseling session, to receive emotional support, and to have an appropriately positioned stoma site. This chapter covers the development of a plan of care for preoperative education for the person anticipating ostomy surgery and the principles of stoma site marking.

CLINICAL PEARL

Support and education in the preoperative is effective in improving recovery after ostomy surgery.

BOX 8-1 Ostomate Bill of Rights

The ostomate shall:

1. Be given pre-op counseling

2. Have an appropriately positioned stoma site

3. Have a well-constructed stoma

4. Have skilled postoperative nursing care

5. Have emotional support

6. Have individual instruction

7. Be informed on the availability of supplies

8. Be provided with information on community resources

9. Have posthospital follow-up and lifelong supervision

10. Benefit from team efforts of health care professionals

11. Be provided with information and counsel from the ostomy association and its members

Patient Assessment

The development of a plan of care for the preoperative education of the patient undergoing ostomy surgery will include the diagnosis that necessitated the surgical procedure, the type and date of surgical procedure, the patient’s understanding of the upcoming procedure, any limitations to learning such as inability to read, physical limitations, and the presence or absence of a support system. Other important assessments include religious affiliation, culture, family, employment status, and medical/surgical history.

Planned Procedure, Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Treatment Plan

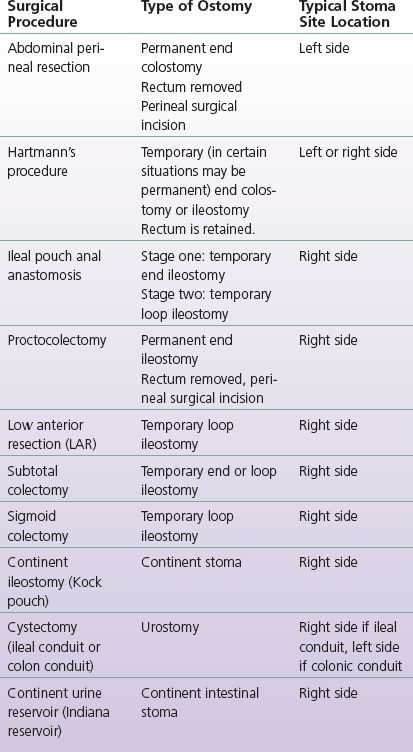

Prior to the preoperative educational session, the wound ostomy continence (WOC) nurse should determine the reason for the surgical procedure and the type of surgical procedure that will be performed (Table 8-1). Reinforce with the surgeon that the stoma construction should protrude 2 to 3 cm above the abdominal plane to direct the effluent into the pouch and promote a good seal of the ostomy appliance system (Cottam et al., 2007). A panel of experts agreed that the ideal stoma should protrude approximately 2.5 cm to prevent peristomal skin irritation (Gray et al., 2013).

TABLE 8-1 Surgical Procedure, Type of Ostomy, Typical Location

Review general postoperative care with the patient and include the probable location of the incision or incisions and the type of tubes they may have such as IVs, abdominal drains, and a urinary catheter. Describe how pain will be managed and the importance of early ambulation. Be sure that the patient understands that he or she will be NPO until bowel function has returned as indicated by the presence of gas in the pouch.

Use the teach-back method to evaluate the patient’s understanding. Suggested examples to ask the patient are as follows: “I want to be sure that I explained your ostomy surgery correctly. Can you tell me what your stoma will look like and how it will function?” or “We covered a lot of information about ostomy surgery today. Can you tell me three things that you learned about your ostomy surgery?”

Many manufacturers of ostomy equipment provide kits for ostomy education to WOC nurses, or are available online. See Appendix C resources for a list of manufacturers.

CLINICAL PEARL

Patients who feel well prepared for ostomy surgery experience better post-operative adjustment to ostomy.

Major Concerns of Patient and Family/Significant Others

Ask the patient and support person to describe their understanding of the surgical procedure, since Weiss (2003) has demonstrated that 40% to 80% of the medical information patients receive is forgotten immediately and nearly half of the information retained is incorrect. Establishing what information the patient knows helps to gain an understanding of his or her grasp of the upcoming procedure and identifies the educational gaps to be addressed during the preoperative session.

The patient and family should be asked what, if anything, they know about ostomy surgery. Encourage them to share concerns they have regarding the upcoming surgery and describe anyone they may have known with an ostomy. This question facilitates the conversation regarding the patient’s worries and possible misconceptions of ostomy care. The patient may have a relative or friend who had a bad experience with an ostomy, and this is a good time to allay any unnecessary fears.

For example, it is not uncommon that an elderly grandparent may have had an ostomy and the pouching system was not effective, causing odor or leakage. This can provide the nurse with the opportunity to explain that the ostomy equipment available today is much improved from the past. Describe that the patient may have been unknowingly in the presence of someone with an ostomy, but since there are no visible signs (odor, bulging under the clothes), the ostomy is not apparent. Many times, people will discover a friend or acquaintance who has an ostomy that they didn’t discuss. Patients who are anxious about a certain aspect of the ostomy will have difficulty learning at the preoperative session. In addition to facing ostomy surgery, many patients are simultaneously faced with a potentially terminal diagnosis or life-changing disease. Patients facing emergency surgery are often in pain, and there may be limited time for the WOC nurse to provide preoperative education.

Barriers to Self-Care

Psychological

There is a good deal of psychological stress when a patient has been diagnosed and told about the need for surgery. Patients should be encouraged to express fears, concerns, worries, disgust, and potential embarrassment regarding the upcoming surgery that will result in the creation of an ostomy (Dorman, 2009). Patients’ fears can be unfounded and may be easily dealt with calmly. For instance, some patients think their diets will change greatly in the presence of an ostomy, and this is not necessarily true. Other people think their clothing must be loose to accommodate the pouching system and that everyone will know they have an ostomy. Alleviating these fears can help the patients cope with all of the changes they will be facing. A visit from a person with an ostomy might be beneficial and an option to talk with a trained ostomy visitor can be obtained by contacting the UOAA.

Physical

Evaluate the patient’s physical abilities. Note if the patient has physical conditions such as arthritis or stroke that could affect his or her ability for self-care. Does the patient have visual limitations that will need to be considered when teaching the patient how to manage his or her stoma? Inadequate coordination and function as seen in Parkinson disease and poststroke weakness are also barriers to self-care (Dorman, 2009). Reinforce to the patient that self-care can be awkward and frustrating in the beginning, but confidence is gained with experience as patients develop new skills to perform the task of emptying and changing the pouching system.

Dorman (2009) indicates that the physical and emotional disabilities of the surgery may have an impact on the ability to perform ostomy care. If there are disabilities that render self-care difficult or impossible, a caregiver must be identified and included in the pre- and postoperative teaching sessions.

Cognitive

Many people have difficulty reading and understanding medical information. Reinforce that the patient and family can call the ostomy nurse with questions after surgery and discharge. Suggest that the patient start a notebook to write down questions in order to remember to ask the nurse or the doctor. The patient can keep all notes regarding the surgery, phone numbers, Web sites, and other information gathered in this special notebook. For the person who may have problems grasping all of the preoperative information, the family member or support person should be included. People with low literacy skills tend to use family or friends to assist the interpretation of the medical information shared (Weiss, 2003).

Understanding Fears

According to the UOAA, odor control and leakage are two major concerns of the ostomy patients, and these need to be addressed during the preoperative education. An explanation of how odor is managed should be provided in a manner that the patient’s fears are alleviated. Describe to the patient how his or her fear of leakage will be addressed, by instructing the patient in how a pouch seal is maintained. Dietary, clothing, and sexual issues can all be discussed and the patient helped to understand that these challenges are normal and fairly easily managed.

Adopted by the United Ostomy Association House of Delegates at the UOA Annual Conference 1977.

Learning Style/Learning Level

Patients should be asked if they are comfortable with learning by reading or if they prefer another way of learning such as photos, video, or audio instruction. Asking in a shame-free manner will more likely elicit an honest response (Weiss, 2003). If reading is not their preferred manner of learning, offer other methods, for example, watching a demonstration video, practicing on a model, or working with the nurse on changing their pouch as many times as possible. See Box 8-2 for teaching methods.

BOX 8-2 Teaching Strategies and Methods

Verbal instruction

Printed instructional sheets or booklets (many ostomy manufacturers provide comprehensive instruction booklets, the United Ostomy Associations of the America [UOAA] has printed information, or the place of nurse’s employment may provide instruction sheets)

Photos

Illustrations or diagrams

Plain paper with pen to draw diagrams

Models made by the nurse or manufactured models such as VATA anatomical healthcare models (http://www.vatainc.com) or The Anatomical Apron by Joy (http://www.apronsbyjoy.com)

Actual pouch system demonstrations

Videos of people changing the ostomy pouch or sharing testimonials

Valid Web sites (such as manufacturer or UOAA Web sites)

Patient’s Support System

The WOC nurse should determine the patient’s emotional support system. This would be a person who can be available during the preoperative visit and at several postoperative sessions as well as follow-ups and someone the person can call when he or she needs to talk. It is important to include the patient’s support system in the preoperative as well as the postoperative education sessions. When patients are in crisis, specifically facing ostomy surgery, absence of social support may result in poor coping and adapting behaviors (Nichols, 2011).

While it is ideal to meet with the patient several weeks prior to surgery, time may be limited and the appointment may be the same day as the surgery. Factor this timing into the amount of education shared with the patient as you might need to limit the provision of information to addressing the patient’s greatest fears and providing basic information on the skills the patient will need to acquire after surgery. Educational materials regarding the specific type of ostomy planned should be provided. This may include printed instructional sheets or booklets, photos, illustrations, models, pouches, and/or videos (see Chapter 11 for patient education resources).

Guidelines for Preoperative Education

CLINICAL PEARL

Preoperative education should include (1) Brief discussion of anatomy and physiology of affected area, (2) Procedure, (3) Briefly describe lifestyle adjustment, (4) Focus on psychological preparation, (5) Introduction to ostomy equipment (WOCN 2010).

Explanation of Planned Procedure

Anatomy and Physiology

Begin with a simple review of the anatomy and bodily functions. Take time for this review because patients often do not have a clear understanding of how their bodies work or how organs are positioned in the abdomen. Explain the physiology of the abdominal organs, particularly the roles of the gastrointestinal and genitourinary systems. Use a diagram or a model to illustrate the changes associated with the planned surgery. A 3D model helps to reinforce the concepts of the anatomy inside the abdomen. Explain that the actual stoma does not come off or have the ability to move around like the model.

The effect of the surgery on other organs inside the abdomen needs to be explained; many individuals need to be assured that the body can continue to function despite the loss of a portion of the intestinal tract or the bladder. For example, the nurse must be very clear that the patient undergoing urostomy surgery will have a section of the intestine used for urine drainage, but the intestine will be reconnected to function as the normal passageway for stool.

The WOC nurse should identify any other education the patient will need. For example, the patient undergoing a temporary ileostomy for ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA) may be ready to have information regarding diet, sphincter exercises, and skin care.

Bowel Prep

Review the bowel preparation prior to surgery. Be sure to check with the surgeon regarding the current methods to prepare for surgery. Some surgeons require mechanical bowel preparation (MBP); however, according to a Cochrane Review done by Guenaga et al. (2011), the need for MBP prior to elective colorectal surgery is optional. The review did state that colon cleansing preparation is necessary for patients with small tumors or the need to determine the precise location of a lesion. Some surgeons consider MBP potentially harmful (Yang et al., 2013). The solutions do not clean out the colon completely, and leave a watery residue. Studies have indicated that infection rate for operations without MBP is equal to or in some cases less than operations done with the bowel preparation (Ellis, 2010). The authors and researchers unanimously agreed that the use of prophylactic antibiotics is universally accepted as one of the most important steps to prevent infections and complications in colorectal surgery (Guenaga et al., 2011).

Since the type of bowel preps used will depend upon the surgical team, it is important to determine their preferred type of prep. There are many different types of MBP, and some are used alone and some used in combination.

The bowel preparation involves dietary restriction and mechanical cleansing of the gastrointestinal tract with the use of a bowel preparation. Typically, the patient is on clear liquids for one to two days before surgery and begins the mechanical bowel prep the day before surgery. Examples of MBPs are as follows: polyethylene glycol (PEG) electrolyte solution; laxatives (mineral oil, agar, and phenolphthalein); mannitol; glycerin enemas (900-mL water containing 100-mL glycerin); sodium phosphate (NaP) solution; bisacodyl (10 mg) and enemas; diets, low residue, nonresidue, and with clear liquids; and saline enema per rectum (Guenaga et al., 2011).

The most common solutions used prior to colorectal surgery are the PEG solution and the NaP solution. The PEG solution is an osmotic laxative. The large-volume solution causes watery diarrhea to cleanse the stool out of the colon. The PEG laxative solution also contains electrolytes to prevent dehydration and other serious side effects that may be caused by fluid loss as the colon is emptied. Patients complain of the salty taste, nausea, abdominal fullness, discomfort, and vomiting that may be associated with this preparation. The NaP solution is a low-volume, hyperosmotic liquid. The effectiveness of oral NaP solution is generally similar to or significantly better than PEG solution in patients preparing for colorectal surgery. Typically, oral NaP solution is significantly more acceptable to patients than is the PEG solution due to the low volume, but may cause electrolyte imbalances and dehydration (Ellis, 2010; WOCN Bowel Prep for Patients with a Colostomy, 2008).

Stoma Appearance and Function

The WOC nurse should describe how the stoma is created, the appearance of the stoma, and expectations of the stoma output. It is important that the patient understand that the stoma will be red and moist and will have no sensation. Many patients express that since the stoma is red, they associated red with pain or infection. Diagrams or models help to demonstrate the surgical creation of the stoma. An easily accessible method to describe the maturation of a stoma is to suggest that the stoma is matured much like a turtleneck that is everted. Explain the lining of the mouth is much like the appearance of the stoma: red, moist, and soft. The use of analogies is helpful to describe the expected output from the stoma (e.g., ileostomy output is similar to pudding consistency).

CLINICAL PEARL

Technical difficulties of managing the ostomy is negatively correlated with psychosocial adjustment.

Overview of Management

Pouching System Management

Demonstrate the type of pouching system that will be used following surgery. While indicating the features of the pouching system, be sure not to overload the patient with unnecessary information. It is best to only demonstrate one pouch system. Explain that the WOC nurse will help direct the patient to the most appropriate pouching system after surgery.

Emptying

Instruct the patient that the first skill the patient or a caregiver will need to acquire before discharge is to learn how to empty the pouch. Let the patient know approximately how many times in 24 hours he or she will need to check the pouch to see if it needs to be emptied. Describe that most people sit on the toilet and direct the pouch contents into the toilet. If the patient has a urostomy, the pouch may be connected to large capacity drainage system at night. If this is a fecal stoma, the patient may wipe the inside of the pouch tail spout with toilet tissue, apply deodorant (if used), and reseal or clamp pouch closed. Help the patient to visualize how to accommodate for these changes in the home setting.

Changing

Provide the patient with an overview on changing the pouching system (Box 8-3). Patients should understand that they will plan a pouching system change on a routine scheduled basis. They will practice changing the pouch while in the hospital but may not acquire the skills prior to discharge and in most cases will have home care nursing to continue to work toward independence in stoma care. Be sure the patients understand that they will go home with ostomy supplies and written instructions to use as they work toward acquiring the necessary skills.

BOX 8-3 Pouching Overview

Pouches are available in different sizes, shapes, and materials.

Features include one- and two-piece systems.

Pouching systems are odor proof.

Usual wear time is four days (Richbourg et al., 2007).

Follow-up with the ostomy nurse should be done on a routine visit and as needed.

Importance of Peristomal Skin Management

Be sure the patient understands that the skin around the stoma should not be reddened or sore and must be maintained intact to avoid problems with the pouch seal. Patients need to understand the principles of ostomy care to prevent skin irritation or redness and to apply a pouch system securely. The skin around the stoma should be healthy, and the appliance should not leak between planned changes. Several studies have shown that some patients do not seek assistance for signs of peristomal skin breakdown. Erwin-Toth et al. (2012) revealed that 61% of participants had signs of peristomal skin disorder upon inspection by the WOC nurse. Reinforce the availability of the WOC nurse for follow-up care; one method is to provide a discharge packet with a follow-up appointment after discharge with the ostomy outpatient clinic.

Obtaining and Paying for Supplies

Instruct the patient that most insurances cover the majority of the cost of ostomy supplies. Since insurance coverage varies, the patient should check with the insurance provider to verify coverage of the ostomy supplies and to determine if there is a preferred vendor. The patient also needs to know that he or she may need a prescription to obtain ostomy supplies.

CLINICAL PEARL

Important considerations in pouching system selection include stoma type and location, abdominal contours, lifestyle, personal preference, visual acuity and manual dexterity.

Attention to Sexual Concerns/Explanation of Potential Sexual Dysfunction

Chapter 13 describes the potential impact of an ostomy on body image and sexual function. The topic of sexuality may be difficult for the patient to broach but is usually a concern, and it is important that the nurse assess the patient’s need to learn about sexuality with an ostomy and to help identify the need for further counseling. The PLISSIT counseling model (described in Chapter 13) highlights the four levels of sexual counseling, Permission, Understanding-Limited Information, Specific Suggestions, and Intensive Therapy (Anon, 1987), and the WOC nurse is encouraged to intervene at the permission and limited information level. This is where the patient is given permission to acknowledge the need for the discussion, and in the simple explanation phase, some simple suggestions for initial sexual encounters after surgery such as emptying the pouch and checking the seal, clothing options, for example, and the patient should be encouraged to ask specific questions.

Patients and their significant others need reassurance that sexual enjoyment can still be a part of their lives, despite the alteration in physical changes (Junkin & Beitz, 2005). The stoma itself should not be used for sexual intimacy, as it is easily damaged and is not an erogenous area.

Basic Explanations Regarding Lifestyle Issues

Diet

Many patients assume that they will need to alter their diet following ostomy surgery. Let the patient know that he or she may have a restricted diet after surgery up to approximately 6 weeks. Most people with ostomies will not have to follow a diet once surgical healing has taken place.

Activity

Determine whether the patient is concerned about resuming normal activity after surgery. Explain that the pouch system should not interfere with activity, and give specific examples of how the patient can integrate the ostomy into his or her lifestyle. Patients often wonder if the pouch can get wet. Assure the patient that typically a daily shower is acceptable, and in some cases, submersion under water for a length of time such as swimming or hot tub may require extra waterproof tape, applied around the barrier edges. Prior to bathing, the seal should be checked, and many people use tape to “picture frame” the four edges of pouch adhesive to further protect from leakage; tape may be paper or waterproof.

Clothing

Discuss the patient’s current clothing and determine if there are any challenges the patient will encounter. Most people are able to return to their former clothing styles after surgery.

Medications

Some medications or nutritional supplements may change the color, odor, or consistency of the stool or urine. Certain medications may not be completely absorbed (see Chapter 12 for more information). For example, in a patient with an ileostomy, time release capsules are not recommended as they may pass through the stoma without breaking down. Medications may need to be converted to liquid form to get the full benefit of the medicine.

Travel

Be sure the patient knows that there are no limitations to travel with the ostomy. Patients should carry ample amount of supplies with them when they travel and to be aware that certain screening processes, when flying, may note the presence of a pouch. Some airport screening systems will detect the presence of a pouching system and require a personal screening. These screenings are usually very professional, in private with two of the same sex officers, and the TSA staff will be discreet to limit embarrassment. This is done for everyone’s safety and is conducted as efficiently and quickly as possible. The UOAA has a travel card that can be carried while traveling that explains some of the conditions associated with an ostomy; copies can be obtained from http://www.ostomy.org/uploaded/files/travel_card/Travel_Card_2011b.pdf.

Acknowledgment of Normal Stages of Adjustment

Adjustment to a new stoma requires a period of time to incorporate the stoma into the patients’ life and to acquire the necessary skills to manage the stoma. Chapter 13 describes the stages of adjustment. Patients should understand that adjustment to an altered body image and function takes time and energy. They should also be aware that the WOC nurse will be available for consultation after discharge for any challenges that arise.

Determination of Need for Referrals

Ostomy Visitor

Patients facing ostomy surgery are at all levels of acceptance. Patients may be ready to accept the upcoming changes, but most patients need further assistance. One suggestion is to refer the patient to a trained visitor who has an ostomy or to refer the patient to an ostomy support before the ostomy surgery. There are local and national ostomy support groups affiliated with the UOAA. The people in these groups have experienced the physical and emotional stressors associated with disease, surgery, body image changes, and lifestyle changes associated with an ostomy. Some local chapters or groups offer Ostomy Education Days to provide all patients with ostomies the opportunity to learn more about having an ostomy, receive encouragement, and see new supplies at a vendor fair. Despite advances in ostomy system technology, many patients still experience problems with psychosocial adjustment.

CLINICAL PEARL

Many patients relate that the personal turning point in learning to accept the ostomy was the moment he or she met another person with a similar ostomy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Stoma Siting

Stoma Siting Documentation

Documentation Conclusions

Conclusions