Chapter 24 Anatomy of male and female reproduction

After reading this chapter, you will have:

The pelvis

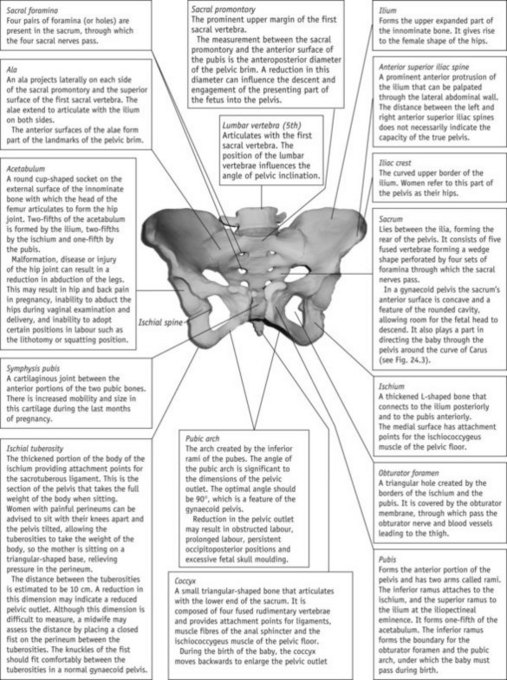

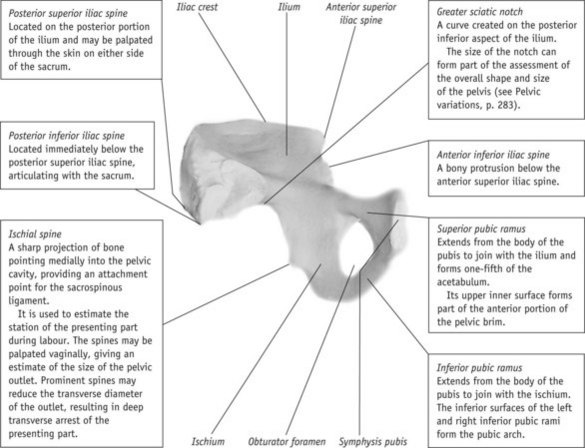

The pelvis consists of four pelvic bones (see Fig. 24.1):

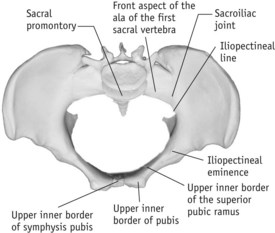

Figure 24.1 The female pelvis. A. Anterior view of pelvis. B. Inner surface of left innominate bone.

The innominate bones are each divided into three regions:

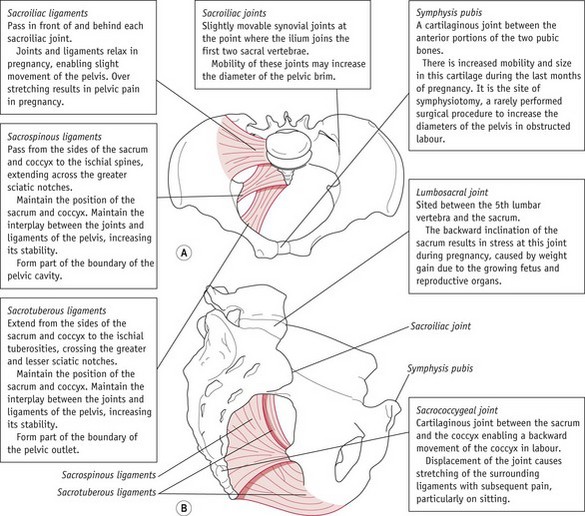

Joints and ligaments of the pelvis

The joints of the pelvis connect the innominate bones at the pubis anteriorly and to the sacrum posteriorly, and the sacrum to the coccyx (see Fig. 24.2). These joints are cartilaginous in type, consisting of plates of fibrocartilage. The pelvis also provides attachment points for ligaments, which are bands of tissue connecting two structures. In normal circumstances, ligaments do not possess the ability to stretch, and therefore prevent excessive movements within the joints, enhancing stability.

In pregnancy, the hormones relaxin, progesterone and oestrogen affect the joints and ligaments, enabling some movement of the joints to facilitate birth. Pelvic pain sometimes occurs during pregnancy, birth or post partum and is thought to be linked to overstretching of ligaments in the pelvis and lower spine (Rost et al 2004).

The true pelvis

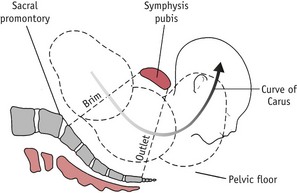

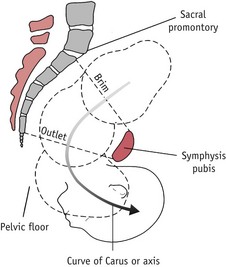

The true pelvis, through which a baby negotiates passage during labour and birth, is the most significant part of the pelvis. This is divided into three regions, known as the brim, cavity and outlet (see Fig. 24.3). As the presenting part descends into the pelvis, the baby negotiates each aspect of the true pelvis simultaneously. For example, in a cephalic presentation, as the baby’s head crowns, the presenting part negotiates the outlet, most of the baby’s head is in the cavity and the shoulders are at the brim.

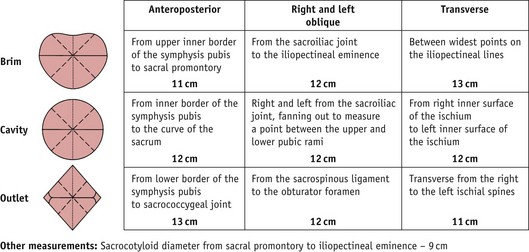

Pelvic measurements (Fig. 24.4)

The pelvic brim is the inlet to the true pelvis and is almost circular, except posteriorly, where the sacral promontory juts into the brim (see Fig. 24.5).

The landmarks of the pelvic brim describe the interplay between the fetus and the pelvis as the presenting part descends, and are a fundamental part of the assessment of descent and engagement of the presenting part. It is not the components of the brim that are important, it is the part that the brim plays as a whole in the assessment of progress during pregnancy and labour. This is the first test that the fetus has to pass as it descends through the pelvis. The midwife assesses engagement of the presenting part during abdominal and vaginal examinations (see Chs 35–37).

The pelvic outlet is diamond shaped and partly bound by ligaments. It can be described in two ways:

The anatomical boundaries for the outlet of the pelvis are:

The obstetric outlet is bounded by:

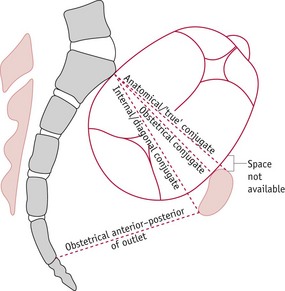

Pelvic conjugates

A conjugate is a measurement taken from one point in the pelvis to another. In midwifery there are the anatomical, obstetrical and internal (diagonal) conjugates (Fig. 24.6).

Internal or diagonal conjugate

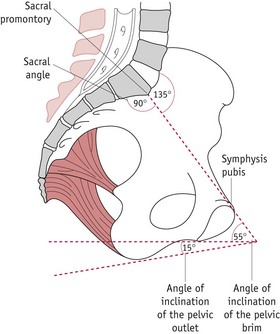

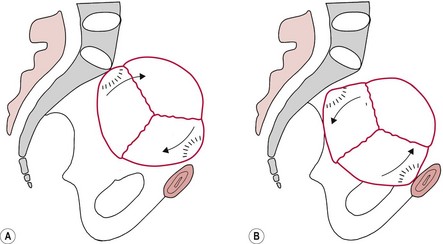

Angles and planes

The term plane describes the relationship between the pelvis and a flat surface, such as the floor, highlighting the tilt of the pelvis in a normal female skeleton. Hypothetical angles are then created in relation to the degree of tilt of a particular individual (see Figs 24.7 and 24.8), which provide a representation of the angles in relation to the planes of the pelvis. Figure 24.8 shows the axis (curve of Carus), an imaginary line through which a fetus rotates as it passes through the pelvis.

Reflective activity 24.2

Rotate Figure 24.2 to represent the woman in a variety of positions, i.e. standing, ‘all fours’ and squatting. Note the direction of the presenting part of the fetus during descent in all positions. What is the impact of these positions on labour?

The subpubic angle is between the two inferior pubic rami forming the pubic arch (Fig. 24.1). In a gynaecoid pelvis, this should be approximately 90°, enabling two finger widths to sit in the apex of the pubic arch during vaginal pelvic assessment.

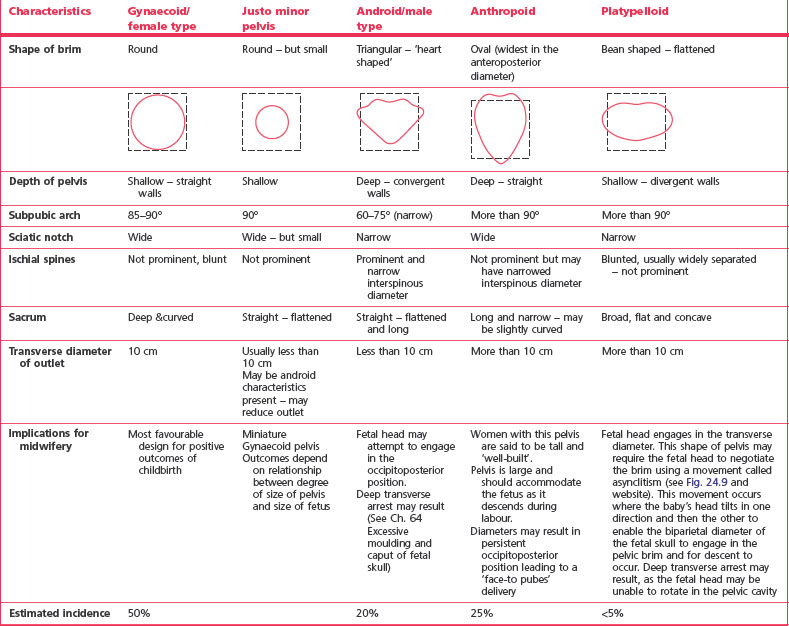

Pelvic variations

Although there are four recognized pelvic categories (Caldwell et al 1940) (Table 24.1), variations within these categories can occur. Some women may have mixed features, such as a gynaecoid posterior pelvis and android forepelvis. The most important factor is the true pelvic space available for the fetus to descend and emerge from the pelvis. The pelvic size and shape cannot be viewed in isolation from other factors, such as position and size of fetus and processes of labour.

Other factors that may influence the size and shape of the pelvis include:

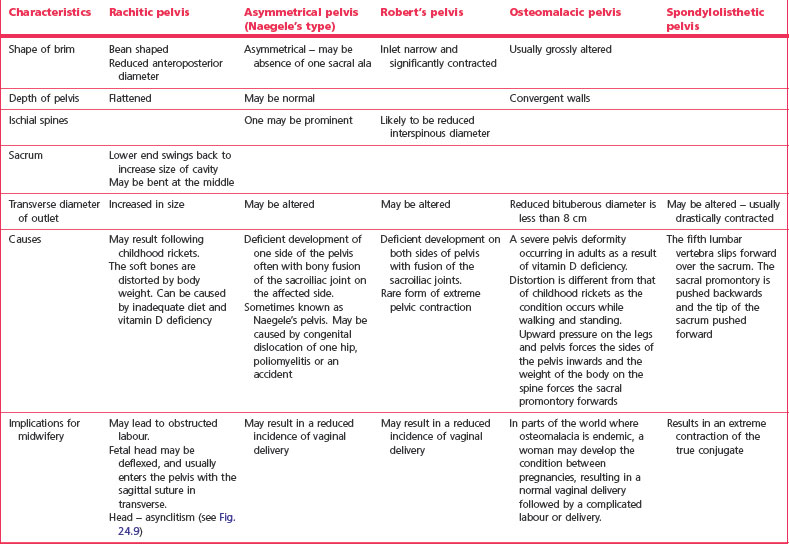

Other pelvic types identified

Any injury or disease of pelvic bones may significantly affect the dimensions of the pelvis, impacting on the outcome of labour and birth. Table 24.2 outlines the classification and characteristics of unusual pelves, each of which may have a mixture of characteristics, with the shape depending upon the degree and timing of damage. It is important that the midwife assesses women at risk of pelvic dysfunction as early as possible antenatally.