Chapter 5 Evidence-based practice and research for practice

After reading this chapter and using the website, you will be:

Introduction

An essential skill for all professionals is using evidence in practice. Being able to determine the quality of research or information upon which evidence is based is a necessary skill for all midwives. Evidence-based healthcare should be the foundation for all policy decisions made within the health service and by midwives (DH 1997, 1999; 2008). Having the appropriate knowledge to evaluate research and evidence to assist in decision-making with women and families, appropriate to their individual needs, requires development of knowledge and skills with understanding of information, resources and women’s views.

What is evidence?

Evidence is a familiar concept within a legal context, where it has been defined as information which may be presented to a court of law, in order for a decision to be made about the probability that a claim is true. In other words, it is the information on the basis of which facts are proved or disproved (Keane 2008), where evidence is sought for the basis of clinical decision-making.

Research

All rigorous research is designed to produce evidence which gains strength because built into the research process are mechanisms that act as internal challenges to address some of the shortcomings identified above. This is true of both quantitative and qualitative research approaches, although they vary in the challenges they pose (Bryman 1992). The research process is systematic and logical with strategies to:

In designing and reporting research, it is essential to be clear in:

Quantitative studies will effectively:

Qualitative research must fulfil similar criteria, although the terminology used differs, arising from different assumptions about the nature of investigation that may arise from a problem or a research question (Denzin & Lincoln 2005). Researchers in this field will present support for:

The decisions at each stage of the research process are generated within, and selected by, individuals whose worldview and values have been shaped within a particular social and professional context. Thus, knowledge is shaped by its social context (Davis-Floyd & Sargent 1997, Downe & McCourt 2008, Jordan 1993). In this sense, there can be no ‘absolute truth’. An awareness of this can be a fruitful basis for generating new questions which reflect and incorporate wider perspectives than just those of the medical or other professions.

However, even in its own terms, research cannot offer finality or certainty in its investigation of the world (Downe & McCourt 2008). Research studies can only present a partial perspective on the questions investigated:

Even when these factors have been well considered and addressed within the research design and interpretation of findings, the applicability of results to wider spheres may be affected by small sample size, contextual factors or the acceptance of the study findings (see Downe & McCourt 2008) – for example, the series of studies carried out to investigate active management of the third stage of labour, in which selection of subjects, preparation of midwives and interpretation of data have all given rise to questions affecting the translation of research findings into practice.

Limitations can be addressed in a number of ways. For a single research report, applying a strategy for rigorous critical appraisal (CASP 2010, Greenhalgh 2006) can enable the practitioner to distinguish between findings that are sound and those that are not.

Systematic review:

Techniques such as systematic review attempt to address the limitations of single studies and the ambiguity of study findings. This strategy involves systematically searching for a comprehensive sample of studies on a particular issue, including a wide range of publications and the so-called ‘grey literature’ of unpublished studies. It is an analytical tool to synthesize information (Brownson et al 2003).

A systematic review is a rigorous way of examining the methodology and findings of individual studies in order to overcome the limitations discussed above – for example, the problems of generalizing from small local samples or evaluating conflicting results. By validating study methodology and findings, the systematic review identifies those that can be confidently applied in guiding practice (Mulrow 1994).

Meta-analysis:

This further development of systematic review involves grouping similar studies and systematically applying particular research questions, as identified by a systematic review, and subjecting those data to further statistical analysis (see Enkin et al 2005, Olsen 1997, Olsen & Jewell 1998).

Whilst these strategies for comprehensive analysis can offer guidance for evidence, they are not without limitations (see Trinder & Reynolds 2000). It may be difficult to source the full range of information about a particular topic for study – for example, obtaining all sources, as a result of language differences, variations in the forms of study, or dissimilar inclusion and/or exclusion criteria. Furthermore, applying generalizable conclusions to a whole population may be neither individualized nor culturally or socially appropriate. However, the experience of dexamethasone demonstrates another obstacle to an evidence-based approach: ‘Despite repeated randomised trials in 1987 providing incontrovertible evidence in favour of antenatal corticosteroid therapy, obstetricians all over the world have been slow to adopt this treatment. The cause of this reluctance is unclear …’ (Crowley 2001) (see website for further debate).

Evidence derived from current literature, primary research studies, systematic reviews and meta-analyses or in-depth literature reviews (Gray 2001, Hart 1998) are not the only form available to practitioners. Practice guidelines, issued by local NHS standard-setting committees, by the Royal Colleges with joint statements on best practice, government recommendations or WHO initiatives, when they are based on critically appraised evidence and referenced as such, present evidence in a form which is easily accessible and applicable to practitioners (see website for sources).

Hierarchy of evidence

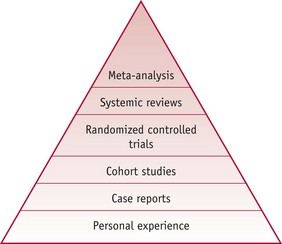

The literature promoting an evidence-based approach to healthcare (see Gray 2001, Greenhalgh 2006, Sackett et al 2000, amongst others) suggests a hierarchical order of value for different sources of evidence. This places a hierarchy in order of:

Methods at the ‘top end’ of the above hierarchy are valued more highly because they have mechanisms built into them which are intended to counter bias (Fig. 5.1).

However, it needs to be remembered that no one method is free from bias and therefore all evidence must be examined in a critical way before it can be used. Whilst personal experiences and knowledge are additional sources of evidence which should inform practice and research at every level, all evidence needs to be judicious in its use for each woman and baby and their individual context (Sackett et al 2000). Many issues requiring clinical decisions have not yet been studied in a systematic way and therefore personal experience and case reports remain important and essential in clinical decision-making (Walsh 2008).

What stimulates the search for evidence to use in practice?

The search for evidence may be generated when practitioners or service users try to challenge the perpetuation of traditional practices. Early research pioneers in midwifery used their findings to change practice and challenge traditions (Romney 1980, Romney & Gordon 1981, Sleep et al 1984). This may stem from the desire to confirm and disseminate personal approaches to clinical care (McCandlish et al 1998). Whilst it may arise from an interest in investigating the nature of midwifery practice, it may also be stimulated by the numerous debates that surround the provision of maternity care – such as antenatal care (Sikorski et al 1996), place of birth (Olsen 1997), nutrition in labour (Scrutton et al 1999), or midwifery-led care (Hatem et al 2008).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree