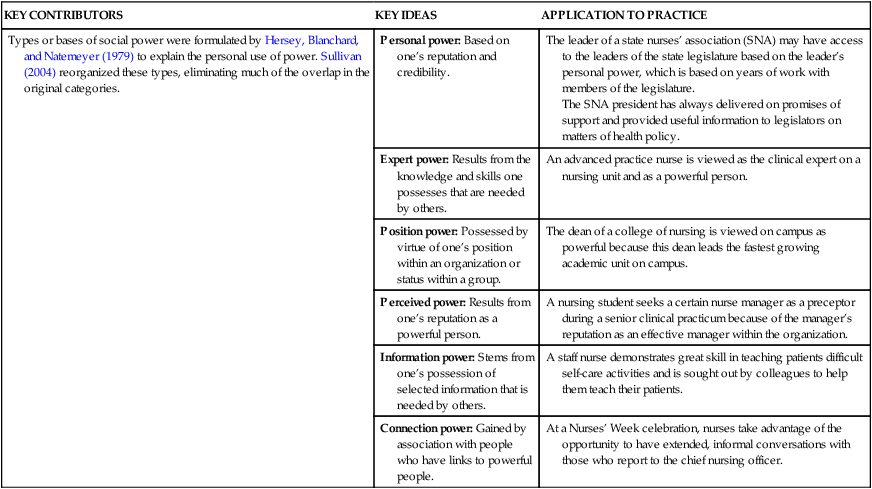

• Explore the concepts of professional and legislative politics related to nursing. • Value the concept of power as it relates to leadership and management in nursing. • Use different types of power in the exercise of nursing leadership. • Develop a power image for effective nursing leadership. • Choose appropriate strategies for exercising power to influence the politics of the work setting, professional organizations, legislators, and the development of health policy. The word power comes from the Latin word potere, meaning “to be able.” Simply defined, power is the ability to influence others in an effort to achieve goals. Power was once considered almost a taboo in nursing. In nursing’s formative years, the exercise of power was considered inappropriate, unladylike, and unprofessional. During nursing’s earliest decades in America, many decisions about nursing education and practice were made by persons outside of nursing (Ashley, 1976). Nurses began to exercise their collective power with the rise of early nursing leaders such as Lillian Wald, Isabel Stewart, Annie Goodrich, Lavinia Dock, M. Adelaide Nutting, Mary Eliza Mahoney, and Isabel Hampton Robb and the development of organizations that evolved into the American Nurses Association (ANA) and the National League for Nursing (NLN). As we experience a new and different era of nursing shortage, there are still some nurses who see themselves as powerless and oppressed, demonstrating aspects of oppressed group behavior. Roberts (1983) addressed the historical evidence of oppressed group behavior among nurses, based on models developed from the study of politically and economically oppressed populations. Oppressed group behavior is apparent when a population is dominated by another group. This subordinate or oppressed group begins to take on the characteristics of the dominant group and reject the characteristics of their own group, although this behavior fails to create a balance of power with the dominant group (Roberts 1983). Matheson and Bobay (2007) conducted a review of the literature to validate oppressed group behavior in nursing. They noted that nurses continue to demonstrate some of the behaviors characteristic of oppressed groups, but they could not validate that these behaviors occur directly as a result of oppression by outside groups. Among nurses, oppressed group behavior is manifested in low self-esteem (e.g., “I’m just a nurse”), passive aggressiveness (e.g., nurse-on-nurse bullying), distancing oneself from other nurses (e.g., the failure of nurses to join professional organizations), and engaging in intragroup conflicts (e.g., “infighting” or horizontal violence) (Matheson & Bobay, 2007; Roberts, 1983). Politics can be defined in many ways. One simple definition of politics that this author uses when teaching health policy and politics in nursing is “a process of human interaction within organizations.” Politics permeates all organizations, including workplaces, legislatures, professions, and even families. Young children often learn that one parent is more likely to readily give permission for special activities or more likely to buy toys and other desired items. They quickly learn to ask permission or ask for a desired item from that parent before asking the other. This is an unwritten political rule in many families. Political activism should be an unwritten rule in nursing (see the Literature Perspective at right). The model of political activism, noted below, is based on elements from models of political activism (Leavitt, Chaffee, & Vance, 2007). This model can be applied to the political development and activism of individual nurses related to both professional and legislative political arenas (Kelly, 2007): 1. Apathy: no membership in professional organizations; little or no interest in legislative politics as they relate to nursing and health care 2. Buy-in: recognition of the importance of activism within professional organizations (without active participation) and legislative politics related to critical nursing issues 3. Self-interest: involvement in professional organizations to further one’s own career; the development and use of political expertise to further the profession’s self-interests 4. Political sophistication: high level of professional organization activism (e.g., holding office at the local and state level) moving beyond self-interests; recognition of the need for activism on behalf of the public and the profession 5. Leading the way: serving in elected or appointed positions in professional organizations at the state and national levels; providing true leadership on broad healthcare interests within legislative politics, including seeking appointment to policy-making bodies and election to political positions Some nurses, including both new graduates and seasoned veterans, have too often viewed power as if it were something immoral, corrupting, and totally contradictory to the caring nature of nursing. However, the definition on p. 176 (the ability to influence others in an effort to achieve goals) demonstrates the essential nature of power to nursing. Nurses routinely influence patients to improve their health status, an essential element of nursing practice. When nurses provide health teaching to patients and their families, the goal is to change patient/family behavior to promote optimal health. That is an exercise of power in nursing practice. Changing the behavior of one’s colleagues by instructing them about a new policy being implemented on the nursing unit is another example of how nurses exercise power. Coaching nurses to improve their performances is an exercise of power. Serving as the chief nursing officer of a hospital, managing a multimillion-dollar budget, demonstrates another exercise of power. Social scientists have studied the use and abuse of power in human organizations. They have analyzed and categorized the sources and applications of power in human experience. Hersey, Blanchard, and Natemeyer (1979) offer a classic formulation on the basis of social power. Sullivan (2004, p. 33) offers a revised view of types of power that readily apply to the efforts of nurses in the workplace, in professional organizations, and in politics (see the Theory Box on p. 180). These types of power are not mutually exclusive. They are often used in concert to exert influence on individuals or groups. Nursing’s early history in the United States was marked by powerlessness (Ashley, 1976). Nurses were absent from the decision-making processes about their education, practice, and employment. As the social, political, and economic status of women and nurses changed, so did the exercise of power by nursing as a profession and nurses as individuals. Powerlessness, a behavior still exhibited by some nurses, results in negative emotions such as apathy and anger. This can result in a workplace culture that is marked by conflict, anger, and other dysfunctional behaviors. Sharing power and facilitating the empowerment of colleagues so that they exercise their power are strong forces in creating vibrant workplace cultures. Empowerment is a term that has come into common usage in nursing in recent years. It has been used extensively in the nursing literature related to administration and management; it is also highly relevant to the domain of clinical practice. Empowerment is the process of exercising one’s own power. It is also the process by which we facilitate the participation of others in decision making and taking action so they are free to exercise power (Ozimek, 2007). Empowerment is consistent with the contemporary view of leadership, a paradigm that is exemplified by behaviors characteristic of all nurse leaders: facilitator, coach, teacher, and collaborator. Nursing leaders, whether in their employment settings or in professional organizations, exercise power in making professional judgments in their daily work. Empowerment is the process by which power is shared with colleagues and patients as part of the nurse’s exercise of power. This is in sharp contrast to traditional conceptualizations of power, a patriarchal model of power that relies on coercion, hierarchy, authority, control, and force. Viewed with a feminist perspective, empowerment is supported through collaboration, not competition and power plays (Sullivan, 2004). • Nurses who view power as finite will avoid cooperation with their colleagues and refuse to share their expertise. • Nurses who view power as infinite are strong collaborators who gain satisfaction by helping their colleagues expand their expertise and their power base. • Self-image: thinking of oneself as powerful and effective • Grooming and dress: ensuring that clothing, hair, and general appearance are neat, clean, and appropriate to the situation • Good manners: treating people with courtesy and respect • Body language: maintaining good posture, using gestures that avoid too much drama, maintaining good eye contact, and being confident in movement • Speech: using a firm, confident voice; good grammar and diction; an appropriate vocabulary; and strong communication skills.

Power, Politics, and Influence

History

Focus on Power

Empowerment

Strategies for Developing a Powerful Image

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Power, Politics, and Influence

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access