Postoperative Assessment

Anatomic Location and Function

Postoperative Assessment

Following the surgical procedure to create an intestinal stoma, a thorough patient assessment and understanding of the surgical procedure must be completed in order to plan care. The surgical report should be read to determine the type of surgical procedure performed as well as any intraoperative findings such as the type of stoma created, presence of advanced disease, existence of adhesions, and/or unusual findings not anticipated before the surgical event (Sonia, 2013). This information will be necessary to support the patient after surgery. The immediate postoperative notes should be read to understand the patient’s first 24 hours after surgery, noting pain management and participation in ambulation, coughing, and deep breathing. Self-care ostomy management will need to be started as soon as the patient can concentrate on the acquisition of new skills; understanding his or her response to pain management as well as his or her ability to participate in routine postoperative activities may help in knowing when teaching can begin. It is more than likely that the first postoperative teaching session will start within 24 hours after surgery.

Postoperative patient assessment includes the following:

- Incisional integrity noting the type of closure (primary, left open to heal by secondary intention, staples, stitches, liquid bonding agent). If the wound has been approximated and closed, examine the incision and if present the dressing for drainage. Wearing gloves, gently palpate either side of the incision noting the firmness or lack of firmness of the tissue, the temperature of the skin as well as any oozing that might be present while examining the area. Note the color of the skin at the incision and compare to the area outside of the surgical area. If the wound is healing by secondary intention, note the approximate size of the wound, the depth, the quality of the tissue as well as the type of dressing, and the presence of wound drainage (color, amount, presence of odor).

- Presence of abdominal drains noting the insertion site for drainage at the skin/drain interface, the amount of drainage (number of gauze pads used and how often changed), and quality of drainage. Assess how the drain is secured (with or without sutures). Assure that the drainage tube has the suction source intact and that the container is emptied when at least three fourths full and that the amount emptied is captured in the intake and output record.

- Note the amount and frequency of pain medication and the patient’s response to pain medications.

- Assessment of the presence or absence of bowel sounds. Using a stethoscope, listen in the four abdominal quadrants for the presence of bowel activity. Examine the ostomy pouch for the presence of gas; trapped air in the pouch is one sign that bowel activity has returned.

- Gently palpate the abdomen noting firmness and excessive tenderness as indicated by the patient’s response.

- Assess the respiratory status by listening to breath sounds and encourage the use of the incentive spirometer, deep breathing, and coughing.

- Patient’s overall response to the surgery and recovery. It is important to determine the patient’s understanding of his/her role in the postoperative recovery and to educate the patient on meeting goals to help move toward recovery. The patient should be ambulating several times in 24 hours and spending time out of bed to decrease the incidence of postoperative complications and increase strength and endurance. Remind the patient that he or she will need to learn how to empty his or her pouch prior to discharge as well as have a good understanding of how the pouching system will be changed.

- Review of the daily intake (IV fluids and when started oral intake) and output (urinary, stool and, if present, drainage collected in drainage collectors).

CLINICAL PEARL

Examine the periwound skin and determine the amount of space between the wound and the outer footprint of the ostomy pouching system. This information will help in determining the appropriate pouching system to avoid injury to the new surgical wound/incision.

Diet: Once bowel activity has returned, the diet is resumed. For most patients, a clear liquid diet is ordered and the patient instructed to sip a small amount of fluid to determine if he or she can tolerate fluid. Since gas is an issue after abdominal surgery, avoiding a straw is suggested as well as encouraging ambulation to help peristalsis. Once a liquid diet is tolerated, a low-residue diet is ordered; suggest to the patient to eat small frequent meals and to chew all foods well. A fecal stoma will be edematous after surgery, and a low-residue diet will allow the stool to pass through the stoma. The patient with a colon or ileal conduit has a bowel anastomosis (where the conduit was excised) and because of potential edema at the anastomosis, a low-residue diet is preferred.

CLINICAL PEARL

As the patient resumes oral intake, discourage the use of a straw as using a straw can increase the intake of air causing blotting and excessive gas.

Stoma Assessment

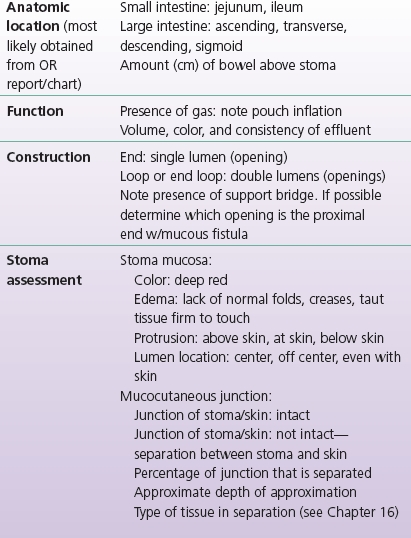

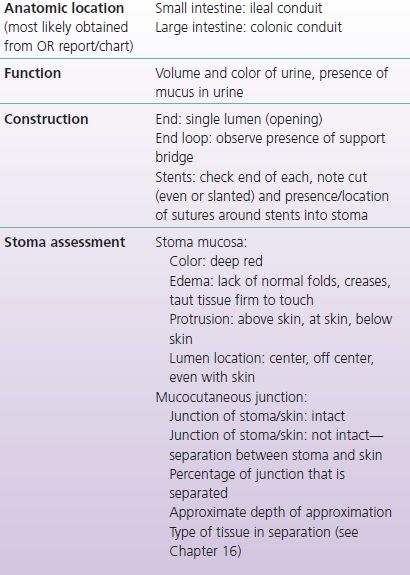

Although the surgical report should describe the type of stoma constructed, a thorough assessment of the stoma should be performed. Assessments will include the anatomic location of the stoma (where in the GI or urinary system), the function of the stoma (volume and consistency), and the type of stoma (the configuration-end, loop or end loop) (Tables 9-1 and 9-2).

TABLE 9-1 Patient with a New Fecal Stoma: Assessment Parameters

TABLE 9-2 Patient with a New Urinary Stoma: Assessment Parameters

Anatomic Location and Function

Review the operative report, the history and physical, and other pertinent notes to understand from what section of the intestine the stoma was created. The function of the fecal stoma will depend upon the location in the GI tract; closer to the end of the colon the output will be less in volume and thicker in consistency. A fecal stoma will generally start to function 1 to 3 days after surgery, commonly earlier when the patient undergoes a laparoscopic surgical procedure. Gas followed by liquid is the initial output of both a small and large bowel fecal stoma. A urostomy will begin to function immediately with the presence of mucus and blood-tinged urine.

A jejunostomy, an opening into the jejunum, will have liquid stoma output, and the volume can be as high as 2,400 mL in 24 hours. An ileostomy is an opening into the last portion of the small intestine, the ileum. The output will vary but is generally about 1,200 mL in 24 hours (Orkin & Cataldo, 2007), and while dietary choices can influence the output, it should vary between a thick liquid to a semi-pasty consistency (like oatmeal). A colostomy is an opening into any section of the colon, and the activity of the colostomy will depend upon the location of the stoma in the colon; closer to the rectum, the output will be pasty to almost formed because the stool has had time to sit in the colon, more fluid is absorbed, and the stool is more formed. Thus, a right-sided colostomy (ascending) will have stoma output similar to that of an ileostomy, a transverse colostomy will have pasty to semisolid stool, and a left-sided colostomy (descending and sigmoid) will have a semisolid to formed stool depending on how close the stoma is to the end of the colon. Colostomy volume will vary from 600 to 1,000 mL in 24 hours depending on the anatomic location. However, after surgery each of the above-noted stomas will have variable function, starting liquid and moving toward “normal” depending on oral intake, medications, and past medical/surgical history. A person who has lost some of the small bowel from other surgeries will have an alteration in the type and volume of stoma output. Examples of diagnoses that can alter stoma function can include Crohn’s disease, previous radiation to the abdomen, ischemic disease, medications, and concurrent treatment such as chemotherapy.

A high-output fecal stoma, usually a jejunostomy or ileostomy, can cause dehydration, slow the rehabilitative process, and in severe cases cause metabolic issues. It is important that ostomy output be carefully measured during the postoperative period, and if the volume of output exceeds what is considered to be the normal amount, a plan of care will need to be worked out that will include ruling out a partial or intermittent bowel obstruction, abdominal sepsis, enteritis (such as Clostridium difficile), or sudden drug withdrawal (opiates or corticosteroids). The plan of care may include the following: the use of isotonic fluids, restriction of hypo- and hypertonic fluids, dietary restrictions of high-sugar foods and fluids, dietary inclusions of starch-based foods, and/or the use of antidiarrheal medications (Baker et al., 2011).

A urostomy can be created from a segment of the colon or ileum. The most common approach is to use the terminal ileum (ileal conduit), but in some cases, the colon is used (colon conduit). The function of a urostomy depends upon kidney function and hydration, but minimal output should be 800 mL/24 hours. It is important to remember that since the intestine is used to make a conduit, there will be at least initially a large amount of mucus expelled from the stoma. The intestinal mucosa secretes mucus to lubricate the intestinal contents and continues to secrete mucus when diverted. For most people with a urostomy, the volume of mucus is high for the first few months and is reported to decrease over time.

An ileal or colon conduit will have stents that are placed at the time of the ureter/conduit anastomosis, the purpose of which is to protect the anastomosis (Fig. 9-1). The length of time that the stents remain in place will depend upon the integrity of the anastomosis, the patient’s ability to heal, and the surgeon’s preference. Note the number of stents (one for each ureter) and the securement device (sutures from the stents to the stoma). Should a stent push out of the stoma before the planned removal, notify the urology team.

FIGURE 9-1. Urostomy with stents.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Stoma Assessment

Stoma Assessment Postoperative Planning

Postoperative Planning Conclusions

Conclusions