Population-Based Public Health Nursing Practice

The Intervention Wheel

Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to do the following:

1. Identify the components of the Intervention Wheel.

2. Describe the assumptions underlying the Intervention Wheel.

3. Define the wedges and interventions of the Intervention Wheel.

4. Differentiate among three levels of practice (community, systems, and individual/family).

Key Terms

advocacy, p. 205

case finding, p. 197

case management, p. 197

coalition building, p. 197

collaboration, p. 197

community, p. 190

community-level practice, p. 191

community organizing, p. 205

consultation, p. 197

counseling, p. 197

delegated functions, p. 197

determinants of health, p. 190

disease and other health event investigation, p. 197

health teaching, p. 197

individual-level practice, p. 191

intermediate goals, p. 210

interventions, p. 191

levels of practice, p. 188

outcome health status indicators, p. 210

outreach, p. 197

policy development, p. 205

policy enforcement, p. 205

population, p. 189

population of interest, p. 189

population at risk, p. 189

prevention, p. 190

primary prevention, p. 191

public health nursing, p. 188

referral and follow-up, p. 197

screening, p. 197

secondary prevention, p. 191

social marketing, p. 205

surveillance, p. 197

systems-level practice, p. 191

tertiary prevention, p. 190

wedges, p. 191

—See Glossary for definitions

Linda Olson Keller, DNP, CPH, APHN-BC, RN, FAAN

Linda Olson Keller, DNP, CPH, APHN-BC, RN, FAAN

Linda Olson Keller is a Clinical Associate Professor at the University of Minnesota School of Nursing. Her research focuses on evidence-based public health nursing practice and the infrastructure of the public health nursing workforce. She spent 20 years of her career in the Office of Public Health Practice at the Minnesota Department of Health. Dr. Olson Keller is certified in Public Health, board certified as an Advanced Public Health Nurse, and is a Fellow of the American Academy of Nursing. She is a frequent national speaker and consultant on public health leadership and practice.

Sue Strohschein, MS, RN/PHN, APRN, BC

Sue Strohschein, MS, RN/PHN, APRN, BC

Sue Strohschein’s public health nursing career spans more than 40 years and includes practice in both local and state health departments in Minnesota. She was a generalized public health nurse consultant for the Minnesota Department of Health for 25 years. Since 2008 she has been with the University of Minnesota School of Nursing as a senior research fellow.

In these times of change, the public health system is constantly challenged to keep focused on the health of populations. The Intervention Wheel is a conceptual framework that has proved to be a useful model in defining population-based practice and explaining how it contributes to improving population health.

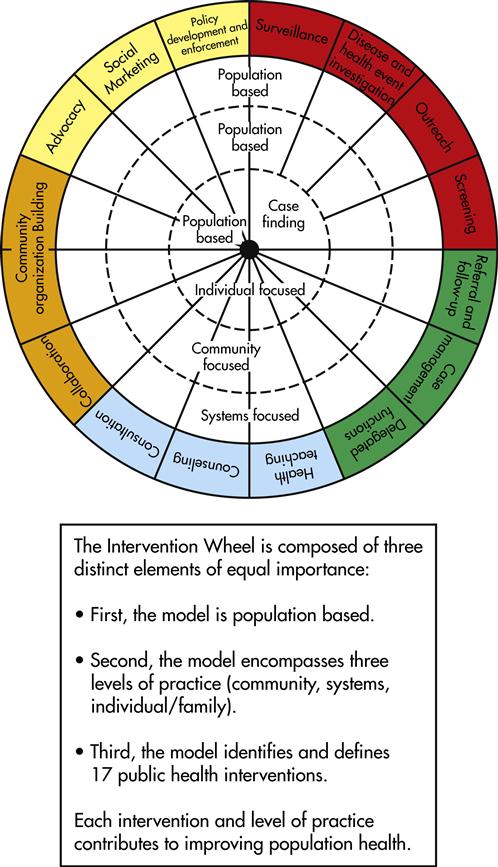

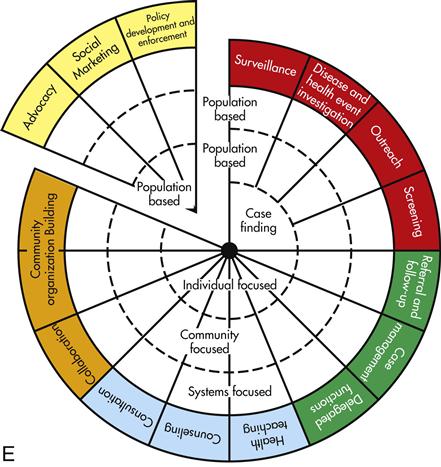

The Intervention Wheel provides a graphic illustration of population-based public health practice (Keller et al, 1998, 2004a,b). It was previously introduced as the Public Health Intervention Model and was known nationally as the “Minnesota Model”; it is now often simply referred to as the “Wheel.” The Wheel depicts how public health improves population health through interventions with communities, the individuals and families that comprise communities, and the systems that impact the health of communities (Figure 9-1). The Wheel was derived from the practice of public health nurses (PHNs) and intended to support their work. It gives PHNs a means to describe the full scope and breadth of their practice.

This chapter applies the Intervention Wheel framework to public health nursing practice. However, it is important to note that other public health members of the interprofessional team such as nutritionists, health educators, planners, physicians, and epidemiologists also use these interventions.

The Intervention Wheel Origins and Evolution

The original version of the Wheel resulted from a grounded theory process carried out by PHN consultants at the Minnesota Department of Health in the mid-1990s. This was a period of relentless change and considerable uncertainty for Minnesota’s public health nursing community. Debates about health care reform and its impact on the role of local public health departments created confusion about the contributions of public health nursing to population-level health improvement. In response to the uncertainty, the consultant group presented a series of workshops across the state highlighting the core functions of public health nursing practice (see Chapter 1 for a description of these core functions). A workshop activity required participants to describe the actions they undertook to carry out their work. The consultant group analyzed 200 practice scenarios developed at the workshops that ranged from home care and school health to home visiting and correctional health. In the final analysis, 17 actions common to the work of PHNs regardless of their practice setting were identified. The analysis also demonstrated that most of these interventions were implemented at three levels: (1) with individuals, either singly or in groups, and with families, (2) with communities as a whole, and (3) with systems that impact the health of communities. A wheel-shaped graphic was developed to illustrate the set of interventions and the levels of practice (see Figure 9-1).

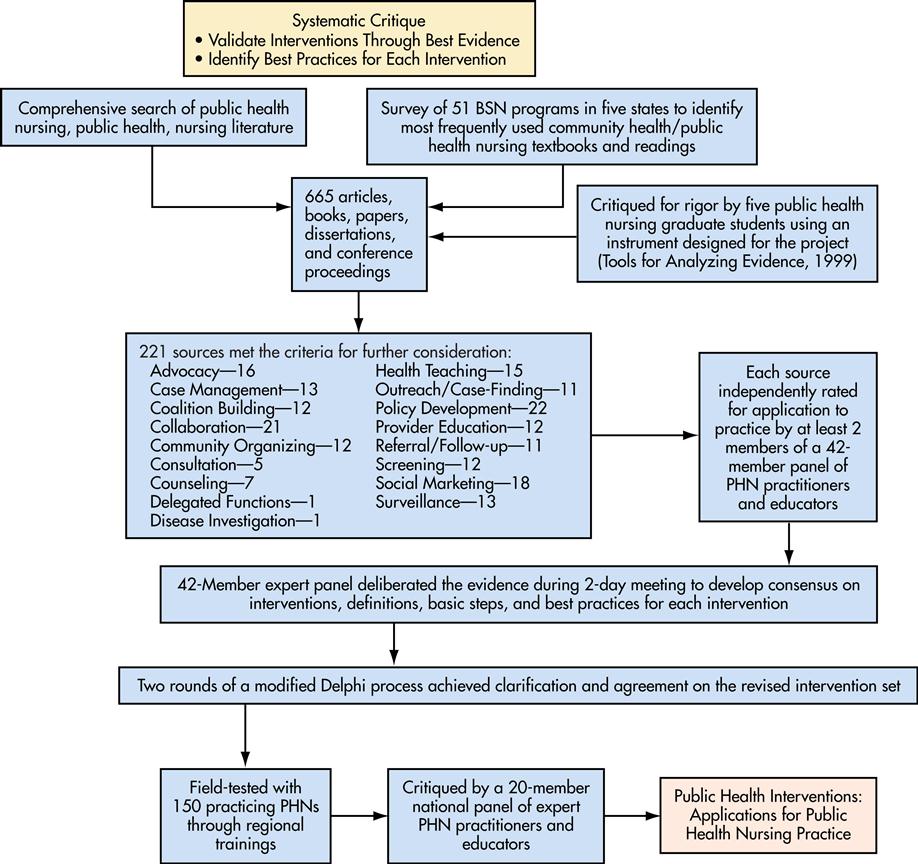

The interventions were subjected to an extensive review of supporting evidence in the literature through a grant from the federal Division of Nursing awarded to the Minnesota Department of Health in the 1990s. In 1999 the PHN consultant group at the Minnesota Department of Health designed and implemented a systematic process identifying more than 600 items from supporting evidence in the literature. These items were rated for their quality and relevancy by a group of graduate nursing students. The resulting subset of 221 items was further analyzed by two expert panels. One panel was composed of public health nursing educators and expert practitioners from five states (Iowa, Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wisconsin). The other panel was a similarly composed national panel. The result was a slightly modified set of 17 interventions. Figure 9-2 graphically illustrates the systematic critique. Each intervention was defined at multiple levels of practice; each was accompanied by a set of basic steps for applying the framework and recommendations for best practices.

Adoption of the model was rapid and worldwide. Since its first publication in 1998, the Intervention Wheel has been incorporated into the public/community health coursework of numerous undergraduate and graduate curricula. The Wheel serves as a model for practice in many state and local health departments and has been presented in Mexico, Norway, Poland, Hungary, Namibia, Kazakhstan, and Japan. It has served as an organizing framework for inquiry for topics ranging from doctoral dissertations (Sheridan, 2005) to the epidemiology of the lowly head louse (Monsen and Keller, 2002). The Wheel’s strength comes from the common language it affords PHNs to discuss their work (Keller et al, 1998).

Assumptions Underlying the Intervention Wheel

As with all conceptual frameworks and models, assumptions are made that help to explain the model or framework. The Intervention Wheel framework is based on 10 assumptions.

Assumption 1: Defining Public Health Nursing Practice

Public health nursing is defined as the practice of promoting and protecting the health of populations using knowledge from nursing, social, and public health sciences (APHA, 1996). The title “public health nurse” designates a registered nurse with educational preparation in both public health and nursing. The primary focus of public health nursing is to promote health and prevent disease for entire population groups. This is done by working with individuals, families, communities, and/or systems.

Assumption 2: Public Health Nursing Practice Focuses on Populations

The focus on populations as opposed to individuals is a key characteristic that differentiates public health nursing from other areas of nursing practice. A population is a collection of individuals who have one or more personal or environmental characteristics in common (Williams and Highriter, 1978). Populations may be understood as two categories. A population at risk is a population with a common identified risk factor or risk exposure that poses a threat to health. For example, all adults who are overweight and hypertensive constitute a population at risk for cardiovascular disease. All underimmunized or unimmunized children are a population at risk for contracting vaccine-preventable diseases. A population of interest is a population that is essentially healthy but that could improve factors that promote or protect health. For instance, healthy adolescents are a population of interest that could benefit from social competency training. All first-time parents of newborns are a population of interest that could benefit from a public health nursing home visit. Populations are not limited to only individuals who seek services or individuals who are poor or otherwise vulnerable.

Assumption 3: Public Health Nursing Practice Considers the Determinants of Health

Health inequities are defined as health status inequalities that society deems to be avoidable or unnecessary (Kawachi, Subramanian, and Alemeida-Filho, 2002). Significant health disparities related to race, gender, age, and socioeconomic status exist within the United States. The Health, United States, 2009 Chartbook (CDC, 2009) provides the following examples:

What are the factors driving these differences? Factors that influence health status across the life cycle are known as the determinants of health. They include: income, education, employment, social support, biology and genetics, physical environment, housing, transportation, and personal health practices.

Resolving health inequities and addressing the determinants of health are key distinguishing characteristics of public health nursing. In a recent interpretive qualitative study of PHNs’ practice in Nova Scotia, researchers found that PHNs routinely implemented “ecosocial surveillance functions” that focused on monitoring changes in social determinants of health. The researchers observed that PHNs “…monitored both bottom-up changes in individual, family, and community determinants of health, and top-down vertical changes or policy directives in the larger system” (Meagher-Stewart et al, 2009, p 557).

Assumption 4: Public Health Nursing Practice is Guided by Priorities Identified Through an Assessment of Community Health

In the context of the Intervention Wheel, a community is defined as “a social network of interacting individuals, usually concentrated in a defined territory” (Johnston et al, 2000).

Assessing the health status of the populations that comprise the community requires ongoing collection and analysis of relevant quantitative and qualitative data. Community assessment includes a comprehensive assessment of the determinants of health. Data analysis identifies deviations from expected or acceptable rates of disease, injury, death, or disability as well as risk and protective factors. Community assessment generally results in a lengthy list of community problems and issues. However, communities rarely possess sufficient resources to address the entire list. This gap between needs and resources necessitates a systematic priority-setting process. Although data analysis provides direction for priority setting, the community’s beliefs, attitudes, and opinions as well as the community’s readiness for change must be assessed (Keller et al, 2002). PHNs, with their extensive knowledge about the communities in which they work, provide important information and insights during the priority-setting process.

Assumption 5: Public Health Nursing Practice Emphasizes Prevention

Prevention is “anticipatory action taken to prevent the occurrence of an event or to minimize its effect after it has occurred” (Turnock, 2009, p 516). Prevention is customarily described as a continuum moving from primary to tertiary prevention (Leavell and Clark, 1965; Novick and Mays, 2001; Turnock, 2009). The Levels of Prevention box provides definitions and examples of the levels of prevention.

A hallmark of public health nursing practice is a focus on health promotion and disease prevention, emphasizing primary prevention whenever possible. Although not every event is preventable, every event has a preventable component.

Assumption 6: Public Health Nurses Intervene at All Levels of Practice

To improve population health, the work of PHNs is often carried out sequentially and/or simultaneously at three levels of prevention (see Figure 9-2).

Community-level practice changes community norms, community attitudes, community awareness, community practices, and community behaviors. It is directed toward entire populations within the community or occasionally toward populations at risk or populations of interest. An example of community-level practice is a social marketing campaign to promote a community norm that serving alcohol to under-aged youth at high school graduation parties is unacceptable. This is a community-level primary prevention strategy.

Systems-level practice changes organizations, policies, laws, and power structures within communities. The focus is on the systems that impact health, not directly on individuals and communities. Conducting compliance checks to ensure that bars and liquor stores do not serve minors or sell to individuals who supply alcohol to minors is an example of a systems-level secondary prevention strategy practice.

Individual-level practice changes knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, practices, and behaviors of individuals. This practice level is directed at individuals, alone or as part of a family, class, or group. Even though families, classes, and groups are comprised of more than one individual, the focus is still on individual change. Teaching effective refusal skills to groups of adolescents is an example of individual secondary prevention strategy level of practice.

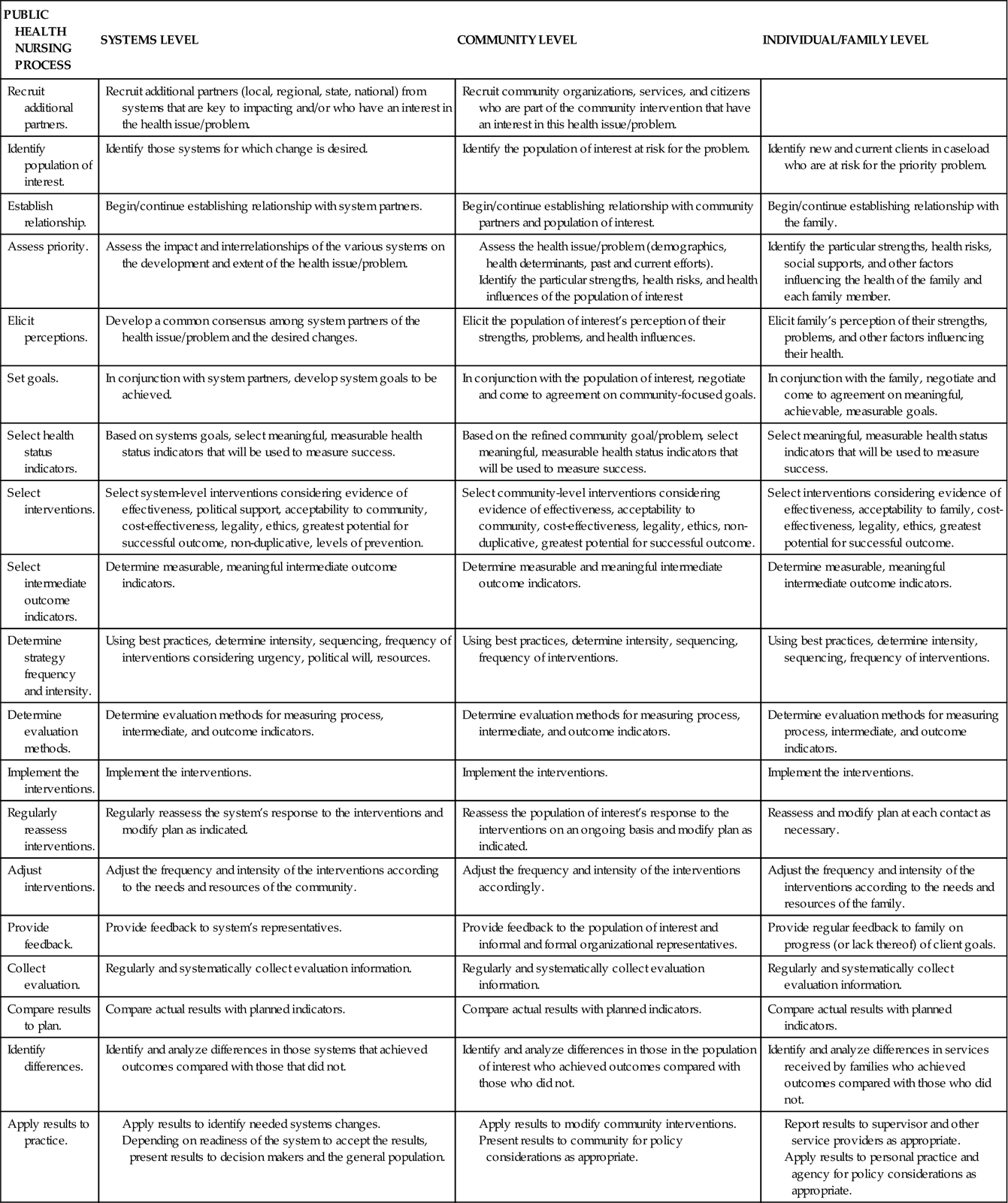

Assumption 7: Public Health Nursing Practice Uses the Nursing Process at All Levels of Practice

Although the components of the nursing process (assessment, diagnosis, planning, implementation, and evaluation) are integral to all nursing practice, PHNs must customize the process to the three levels of practice. Table 9-1 outlines the nursing process at the community, systems, and individual/family levels of practice.

TABLE 9-1

Assumption 8: Public Health Nursing Practice Uses a Common Set of Interventions Regardless of Practice Setting

Interventions are “actions taken on behalf of communities, systems, individuals, and families to improve or protect health status” (ANA, 2010). The Intervention Wheel encompasses 17 interventions: surveillance, disease and other health investigation, outreach, screening, case finding, referral and follow-up, case management, delegated functions, health teaching, consultation, counseling, collaboration, coalition building, community organizing, advocacy, social marketing, and policy development and enforcement.

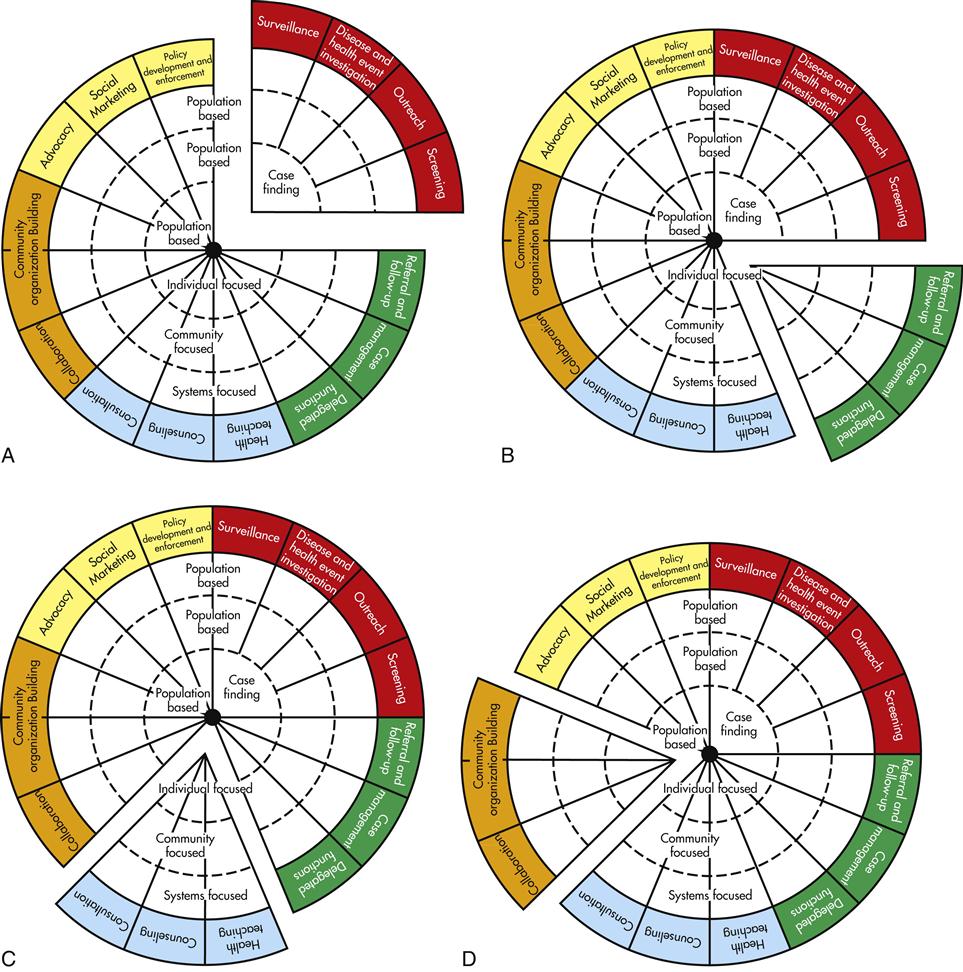

The interventions are grouped with related interventions; these wedges are color coordinated to make them more recognizable (Figure 9-3, A). For instance, the five interventions in the red wedge are frequently implemented in conjunction with one another. Surveillance is often paired with disease and health event investigation, even though either can be implemented independently. Screening frequently follows either surveillance or disease and health event investigation and is often preceded by outreach activities in order to maximize the number of those at risk who actually get screened. Most often, screening leads to case finding, but this intervention can also be carried out independently. The green wedge consists of referral and follow-up, case management, and delegated functions—three interventions that, in practice, are often implemented together (Figure 9-3, B). Similarly, health teaching, counseling, and consultation—the blue wedge—are more similar than they are different; health teaching and counseling are especially often paired (Figure 9-3, C). The interventions in the orange wedge—collaboration, coalition building, and community organizing—although distinct, are grouped together because they are all types of collective action and are most often carried out at systems or community levels of practice (Figure 9-3, D). Similarly, advocacy, social marketing, and policy development and enforcement—the yellow wedge—are often interrelated when implemented (Figure 9-3, E). In fact, advocacy is often viewed as a precursor to policy development; social marketing is seen by some as a method of carrying out advocacy.

The interventions on the right side of the Wheel (i.e., the red, green, and blue wedges) are most commonly used by PHNs who focus their work more on individuals, families, classes, and groups and to a lesser extent on work with systems and communities. The orange and yellow wedges, on the other hand, are more commonly used by PHNs who focus their work on effecting systems and communities. However, a PHN may use any or all of the interventions.

Assumption 9: Public Health Nursing Practice Contributes to the Achievement of the 10 Essential Services

Implementing the interventions ultimately contributes to the achievement of the 10 essential public health services (see Chapter 1). The 10 essential public health services describe what the public health system does to protect and promote the health of the public. Interventions are the means through which public health practitioners implement the 10 essential services. Interventions are the how of public health practice (Public Health Functions Steering Committee, 1995).

Assumption 10: Public Health Nursing Practice is Grounded in a Set of Values and Beliefs

The Cornerstones of Public Health Nursing (Box 9-1) were developed as a companion document to the Intervention Wheel. The Wheel defines the “what and how” of public health nursing practice; the Cornerstones define the “why.” The Cornerstones synthesize foundational values and beliefs from both public health and nursing. They inspire, guide, direct, and challenge public health nursing practice (Keller, Strohschein, and Schaffer, 2010).

Using the Intervention Wheel in Public Health Nursing Practice

The Wheel is a conceptual model. It was conceived as a common language or catalog of general actions used by PHNs across all practice settings. When those actions are placed within the context of a set of associated assumptions or relations among concepts, the Intervention Wheel serves as a conceptual model for public health nursing practice (Fawcett, 2005). It creates a structure for identifying and documenting interventions performed by PHNs and captures the nature of their work. The Intervention Wheel provides a framework, a way of thinking about public health nursing practice. The Public Health Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice includes the Intervention Wheel as one of several public health nursing frameworks used in practice today (ANA, 2007).

Components of the Model

As depicted in Figure 9-1, the model has three components: a population basis, three levels of practice, and 17 interventions.

Component 1: The Model Is Population Based

The upper portion of the Intervention Wheel clearly illustrates that all levels of practice (community, systems, and individual/family) are population based. Public health nursing practice is population focused. It identifies populations of interest or populations at risk through an assessment of community health status and an assignment of priorities.

The population of Sherburne County (Minnesota) increased almost 175% in 25 years (Minnesota Departments of Education, Health, Human Services, and Public Safety, 2007). The numerous new housing developments characterized urban sprawl, which has been implicated in the current obesity epidemic in both children and adults (Dunton et al, 2009; Renalds, Smith, and Hale, 2010). The local health department staff was concerned about the prevalence of obesity in its population. Data from the Community Health Status Indicators’ website showed that 24.1% of the population’s adults were considered obese (USDHHS, 2010). A 2007 state student health survey documented that 25% of ninth-grade girls and 20% of ninth-grade boys in the county were overweight or obese. In this same age group, 76% of girls and 80% of boys reported they were active less than 30 minutes daily. It was clear that Sherburne County had an obesity problem (Minnesota Departments of Education, Health, Human Services, and Public Safety, 2007).

Reversing this trend required reducing barriers to exercise. Health department staff recognized the impact of urban sprawl on their built environment (Renalds, Smith, and Hale, 2010), or the “human-made space in which people live, work and recreate on a day-to-day basis” (Roof and Oleru, 2008). One of the first factors they considered was the walkability of their communities, or extent to which planned transportation networks and public spaces accommodate walking and other forms of physical exercise. Walkability includes: (1) continuous and well-maintained sidewalks, (2) easy access, path directness, and street network connectivity, (3) crossing safety, (4) absence of heavy and high-speed traffic, (5) pedestrian buffering from traffic, (6) land-use density and diversity, (7) street trees and landscaping, (8) visual interest and sense of place, and (9) security (Lo, 2009).

With these data, the public health staff engaged community members to determine the next steps to improve their community walkability. The department asked undergraduate nursing students who were in their public health nursing clinical program to design, implement, and evaluate a walkability project. The students walked over 100 miles and rated the walkability of three different Sherburne County communities. The students analyzed the results and presented recommendations for improvements to the city councils of the three communities. The findings were used by two of the three communities to secure funding for improvements to their community’s walkability (Zoller, 2010).

Component 2: The Model Encompasses Three Levels of Practice

Public health nursing practice intervenes with communities, the individuals and families that comprise communities, and the systems that impact the health of communities. Interventions at each level of practice contribute to the overall goal of improving population health. The work of PHNs is accomplished at all levels. No one level of practice is more important than another; in fact, many public health priorities are addressed simultaneously at all three levels.

One public health priority that almost every PHN will encounter is the potential for the occurrence of vaccine-preventable disease because of delayed or missing immunizations. A recent task analysis of 60 PHNs from 29 states revealed that 93% of all PHNs participated in immunization activities (Keller, 2008). This held true regardless of the PHN’s work setting (e.g., home, clinic, school, correctional facility, childcare center) or the population focus (e.g., maternal-child health, elderly chronic disease management, refugee health, disease prevention and control). Vaccine-preventable diseases, or diseases that may be prevented through recommended immunizations, include diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, polio, mumps, measles, rubella, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, varicella, meningitis, Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib), pneumococcal pneumonia, rotavirus, human papillomavirus (HPV), herpes zoster, and seasonal influenza (CDC, 2010b).

This section illustrates strategies for reducing the occurrence of vaccine-preventable diseases at all three levels of practice. These are only selected examples of strategies to improve immunization rates; it is not an inclusive list.

Community Level of Practice

The goal of community-level practice is to increase the knowledge and attitude of the entire community about the importance of immunization and the consequences of not being immunized. These strategies will lead to an increase in the percentage of people who obtain recommended immunizations for themselves and their children.

At the community level, PHNs work with health educators on public awareness campaigns. They perform outreach at schools, senior centers, county fairs, community festivals, and neighborhood laundromats.

PHNs conduct or coordinate audits of immunization records of all children in schools and childcare centers to identify children who are under-immunized. The PHNs refer them to their medical providers or administer the immunizations through health department clinics.

When a confirmed case of a vaccine-preventable disease occurs, PHNs work with epidemiologists to identify and locate everyone exposed to the index case. PHNs assess the immunization status of people who were exposed and ensure appropriate treatment.

In the event of an outbreak in the community, all PHNs have a role and ethical responsibility to take part in mass dispensing clinics. Mass dispensing clinics disperse immunizations or medications to specific populations at risk. For example, clinics may be held in response to an epidemic of mumps, a case of hepatitis A attributable to a foodborne exposure in a restaurant, or an influenza pandemic in the general population.

Systems Level of Practice

The goal of systems-level practice is to change the laws, policies, and practices that influence immunization rates, such as promoting population-based immunization registries and improving clinic and provider practices.

PHNs work with schools, clinics, health plans, and parents to develop population-based immunization registries. Registries, known officially by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as “Immunization Information Systems,” combine immunization information from different sources into a single electronic record. A registry provides official immunization records for schools, day-care centers, health departments, and clinics. Registries track immunizations and remind families when an immunization is due or has been missed.

PHNs conduct audits of records in clinics that participate in the federal vaccine program. PHNs ascertain if a clinic is following recommended immunization standards for vaccine handling and storage, documentation, and adherence to best practices. PHNs also provide feedback and guidance to clinicians and office staff for quality improvement.

PHNs also work with health care providers in the community to ensure that providers accurately report vaccine-preventable diseases as legally required by state statute.

Individual/Family Level of Practice

The goal of individual/family-level strategies is to identify individuals who are not appropriately immunized, identify the barriers to immunization, and ensure that the individual’s immunizations are brought up to date.

At the individual level of practice, PHNs conduct health department immunization clinics. Unlike mass dispensing clinics, immunization clinics are generally available to anyone who needs an immunization and do not target a specific population. These clinics often provide an important service to individuals without access to affordable health care.

PHNs use the registry to identify children with delayed or missing immunizations. They contact families by phone or through a home visit. The PHNs assess for barriers and consult with the family to develop a plan to obtain immunizations either through a medical clinic or from a health department clinic. The PHN follows up at a later date to ensure that the child was actually immunized.

PHNs routinely assess the immunization status for clients in all public health programs, such as well-child clinics, family planning clinics, maternal-child health home visits, or case management of elderly and disabled populations, and they ensure that immunizations are up to date.

Component 3: The Model Identifies and Defines 17 Public Health Interventions

The Intervention Wheel encompasses 17 interventions: surveillance, disease and other health investigation, outreach, screening, case finding, referral and follow-up, case management, delegated functions, health teaching, consultation, counseling, collaboration, coalition building, community organizing, advocacy, social marketing, and policy development and enforcement.

All interventions, except case finding, coalition building, and community organizing, are applicable at all three levels of practice. Community organizing and coalition building cannot occur at the individual level. Case finding is the individual level of surveillance, disease and other health event investigation, outreach, and screening. Altogether, a PHN selects from among 43 different intervention-level actions.

Table 9-2 provides examples of the intervention at the three levels of practice for each of the 17 interventions.