Introduction

This chapter introduces you to the philosophical assumptions, or set of beliefs, that underlie the research process.

To continue, it is important for us to understand these philosophies, or beliefs, when discussing research because they guide and influence researchers on how to conduct research according to the type of research they are undertaking. Although this chapter introduces you to the idea that there are different types of research that the researcher can use, the types of research themselves are explored more fully in chapter 5 as well as in the web program.

To simplify things here, this chapter focuses on the two main types of research that are in frequent use, namely:

- qualitative research; and

- quantitative research.

In this chapter we explore the philosophical assumptions underlying each type and some of their characteristics. By understanding these different perspectives, you will gain a grounding in the issues addressed in the different types of research. To help you understand the assumptions that underlie research, we begin by looking at qualitative research.

Philosophical assumptions of qualitative research

Creswell (1998: 15) defines qualitative research as:

‘an inquiry process of understanding based on distinct methodological traditions of inquiry that explain a social or human problem. The researcher builds a complex, holistic picture, analyses words, reports detailed views of informants, and conducts the study in a natural setting.’

When you read this definition, you may immediately come to the conclusion that anything to do with research is quite complicated. But as you work through this and subsequent chapters, as well is through the web program, it will all become clear. You do, however, need to read a definition like the one above and at first try to grasp the substance of what is written rather than worrying about individual words.

We can help you to make sense of what Creswell is saying by giving an example of what this means in a healthcare context.

A researcher undertakes a study to examine the experiences of patients who, in the last 12 months, have used respite facilities (facilities that can be used by chronic and/or seriously ill patients for short-term stays in order to give their carers a break, or respite – e.g. a hospice) provided by their local NHS provider. The researcher may choose to interview the patients in order to ask them about their views on the service. The interviews may take place in the patient’s home or at the respite facility. The perspectives provided by the patients are later analysed and a report is produced which gives a picture of the views of the patients who have used the service. So, you can see that qualitative research aims to explore and understand individuals’ beliefs, experiences, behaviour and attitudes. It is therefore not a unitary (single) approach to research, but embraces a number of approaches which have their roots in interpretative methodologies (these occur in research studies in which the data are interpreted in order to give meaning to them and hence to the participants’ lives). Such methodologies seek to explain and critique an understanding of the socially constructed nature of ‘facts’ through which individuals or groups make sense of their everyday lives and interactions (Parahoo 2006). In other words, what occurs in people’s lives are usually situated within their, and possibly others’, families/local/national/international societies, whichever or whatever that might be. There is a social element to everything we do and experience, and this is reflected in our attitudes to, experiences of, confrontations with and perceptions of society and our place in it.

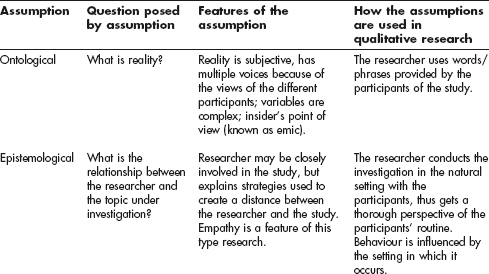

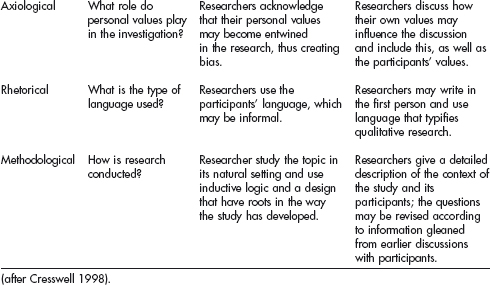

There are five main philosophical assumptions (Guba&Lincoln 1988, Cresswell, 1998) about research, and the explanation of these assumptions has different interpretations in qualitative and quantitative research. Table 2.1 sets out the different philosophical assumptions and how they can be used in qualitative research (after Cresswell 1998). These philosophical assumptions are characteristic of all qualitative inquiries.

Table 2.1 Philosophical assumptions of qualitative research and examples of its use in practice.

Some major characteristics of qualitative research

This is a brief introduction to this type of research study and, as has been stated above, the characteristics of qualitative research are discussed more fully in chapter 5. Patton (2002) succinctly identifies the major characteristics of qualitative research under three strategies:

- design;

- data collection;

- analysis strategies.

These headings are used below to explain the characteristics of qualitative research, and now are briefly discussed.

Design strategies

In qualitative research, ideally:

- Studies are conducted in a natural setting, the purpose being to gain insight and improve our understanding of the topic under discussion by exploring its depth, richness and complexity.

- The design of the study is flexible in order to encapsulate (or include) changes in situations which may develop as the research takes place. For example, research questions may need to be substantially modified whilst the study is under way. Also, the sample of interviewees may need to be modified. In other words, the research is discovery-oriented – it develops as new data are discovered. This design is also described as emergent and open-ended because there are no closed questions or answers – the development of the design is fluid and dynamic, and theory and understanding of the phenomena emerge as the study progresses.

- The participants have specific knowledge concerning the phenomenon (often because they are the ones living with/experiencing it) and thus they are recruited in order to provide an understanding of the issue within a particular context.

Data collection strategies

We can now return to data collection strategies in qualitative research:

- Frequently used data collection methods include observation, interviewing, documents, photographs, videotapes and field notes. These methods allow ‘thick description’ (Patton 2002) and ‘rich information’ (Polit&Beck 2004) to be gathered about individuals’ experiences and viewpoints (see chapter 5 and the web program). In other words, the topic is examined in depth and so the findings are narrow and deep, as opposed to shallow and wide as is often the case with quantitative research (see chapter 5).

- The emphasis is on the researcher-as-instrument (i.e. just as in quantitative research the instrument for the collection of data might be an experiment, or an actual measuring instrument, so in qualitative research it is the researcher who is the instrument for the data collection). The researcher is able to get to know the participants, sometimes over a long period of time, and so the researcher’s views are also important to understanding the situation being explored, as well as to the views of the participants (see chapter 8 and the web program).

- The reality of the process is fluid, dynamic, situational, context-specific and personal; it is therefore socially constructed (i.e. developed within social boundaries, no matter how narrow or broad these might be).

- The data include words, images and categories, rather than just numerical data. In qualitative research, the data can be collected as words, pictures, physical appearance, gestures or music. Indeed, the whole gamut of human experiences and achievements can elicit data in many forms, including numerical (see chapter 8 and the web program).

- The focus is exploratory and descriptive – it describes and explains a phenomenon/situation how will stop.

Analysis strategies

Once we have obtained our data, we need to do something with them – we have to analyse them so that we can start to make sense of them, and give meaning to our findings and to the phenomenon that we are investigating.

Consequently, with regard to the analysis of data, in qualitative research:

- The researcher searches the data for patterns and themes at an early stage, and uses these to explore the data further within the research study.

- This process is one of ongoing inductive analysis. Inductive analysis is analysis which takes us ‘beyond the confines of our current evidence or knowledge to conclusions about the unknown’ (Sloman&Lagnado 2005: 95). We use inductive analysis in order to ascribe properties or relations to one or more things/people based on a number of observations or experiences. From this we can formulate theories based on recurring patterns of phenomena. This procedure/analysis is a common process in qualitative research because it allows the observer/researcher to become immersed in a group. The researcher obtains initial answers from the participants, and from these formulates further questions throughout research study. These theories can continue to change depending on what the observer finds out from the participants or wants to explore.

- Qualitative researchers are interested in making sense of the data – they are interested in the ways in which people try to make sense of their personal worlds and in the societies that they find themselves in, whether that be their family, work, healthcare setting, hobby or sport.

- Understandings and generalisations are primarily grounded (based) in the data that are collected and analysed. It may then be necessary to organise further studies, or access further studies by other researchers, in order to verify what has been theorised from your initial study.

- To help with the verification of the analysis and theories generated from a piece of qualitative research, some researchers send transcripts of the interviews and focus group discussions to the participants and invite their comments on their analysis of the data in order to seek their opinions of the analysis and interpretations.

- Some researchers distinguish their own ‘voices’ from those of the participants and some inform readers of their position or status within the research. For example, they may be in a managerial position and are researching the staff they employ. This relationship should be highlighted in the research and how they have overcome the potential conflict explained to the reader.

- The aim of data analysis is to focus on the relationships of the phenomenon under investigation in order that meaningful insights are provided.

- In reporting their findings, researchers present the diverse voices of the interviewees through stories, narratives and quotations.

In summary, we can see that qualitative researchers are:

- Interested in the process of the phenomena. ‘Phenomena’ is the plural of ‘phenomenon’, and means ‘happenings’, events, occurrences. They may be physical, social, psychological or even metaphysical – but let us not worry about that at this stage.

- Interested in the meanings that people give to their world.

- The primary instrument for data collection and analysis.

- Able to produce a descriptive picture of events in the participants’ own language/pictures.

- Able to build concepts and develop theories using an inductive process (see the second bullet point above for an explanation of induction in research).

Philosophical assumptions of quantitative research

Having briefly explored qualitative research, we can now turn our attention to the second major research paradigm – quantitative research. You will quickly learn that quantitative research is very different from qualitative research in many ways, although their basic aim is the same – to uncover the truth that underlies a phenomenon.