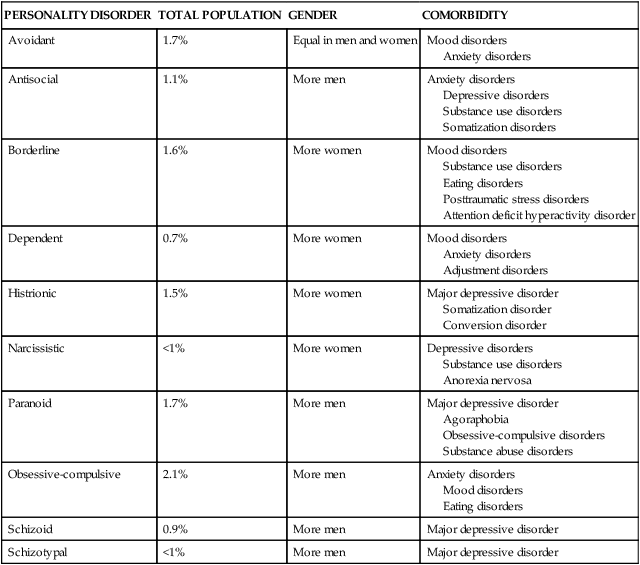

CHAPTER 24 1. Identify characteristics of each of the 10 personality disorders. 2. Analyze the interaction of biological determinants and psychosocial stress factors in the etiology of personality disorders. 3. Describe the emotional and clinical needs of nurses and other staff when working with patients who meet criteria for personality disorders. 4. Formulate a nursing diagnosis for each of the personality disorders. 5. Discuss two nursing outcomes for patients with antisocial and borderline personality disorder. 6. Plan basic interventions for a patient with impulsive, aggressive, or manipulative behaviors. 7. Identify the role of the advanced practice nurse when working with patients with personality disorders. Visit the Evolve website for a pretest on the content in this chapter: http://evolve.elsevier.com/Varcarolis Western scholars such as Hippocrates suggested that personality and general health problems were the results of an imbalance of essential bodily fluids. These fluids, or “humors,” were phlegm (mucous), blood, and bile. The scientist Galen proposed that these humors produced personality profiles of phlegmatic (calm and unemotional), sanguine (lighthearted and unemotional), melancholic (creative and depressive), and choleric (energetic and passionate) (Kagan, 2005). Personality can be described operationally in terms of functioning. We know that personality can be protective for a person in times of difficulty but may also be a liability if one’s personality results in ongoing relationship problems or leads to emotional distress on a regular basis (Clarkin & Huprich, 2011). Personality determines the quality of experiences among people and serves as a guide for one-to-one interaction and in social groups. Based on this description, we can tell when a personality is unhealthy, that is, “when it interferes with, or complicates, social and interpersonal function” (Blais et al., 2008, p. 527). In contemporary society there is a consensus that personality disorders exist on a continuum of severity and likely represent more extreme variations in normal personality development. People with these disorders have difficulty recognizing or owning that their difficulties are problems of their personality. They may truly believe the problems originate outside of themselves. Still others may be unaware that their behavior is unusual, and they may not experience any distress (Skodol & Gunderson, 2008). According to the American Psychiatric Association (2013), there are 10 personality disorders (Box 24-1; also see Table 24-1). Eight of these disorders will be described in terms of prevalence, characteristic pathological responses, and etiology. A vignette is also provided to illustrate each of these disorders. Afterwards, two common and challenging personality disorders, antisocial and borderline, will be described in more depth along with an application of the nursing process. TABLE 24-1 PREVALENCE OF PERSONALITY DISORDERS BY TOTAL POPULATION, GENDER, AND COMMON COMORBIDITIES Data from Torgersen, S. (2009). Prevalence, sociodemographics, and functional impairment. In J. M. Oldham, A. E. Skodol, & D. S. Bender (Eds.), Essentials of personality disorders (pp. 83–102). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing. Paranoid personality disorder occurs at a prevalence rate of about 1.7% in community samples (Torgersen, 2009). This disorder is characterized by a longstanding distrust and suspiciousness of others based on the belief (unsupported by evidence) that others want to exploit, harm, or deceive the person. These individuals are hypervigilant, anticipate hostility, and may provoke hostile responses by initiating a “counterattack.” They demonstrate jealousy, controlling behaviors, and unwillingness to forgive. Paranoid persons are difficult to interview because they are reluctant to share information about themselves. Underneath the guarded surface, they are actually quite anxious about being harmed. Paranoid personality disorder may be found in people who grew up in households where they were the objects of excessive rage and humiliation, which resulted in feelings of inadequacy (Skodol & Gunderson, 2008). Projection is the dominant defense mechanism; they blame others for their shortcomings. Schizoid personality disorder is fairly uncommon and is estimated to occur in around 0.9% of the population (Torgersen, 2009). People with schizoid personality disorder exhibit a poor ability to function in their lives. Relationships are particularly affected due to the prominent feature of emotional detachment. People with this disorder do not seek out or enjoy close relationships and are viewed as loners. Neither approval nor rejection from others seems to have much effect. Friendships, dating, and sexual experiences are rare. Employment may be jeopardized if interpersonal interaction is necessary; individuals with this disorder may be able to function well in a solitary occupation such as a security guard on the night shift. Feelings of being an observer rather than a participant in life are common. Depersonalization, or feelings of detachment from oneself and the world, may be present. Schizotypal personality disorder is more common in men than women and occurs at a rate of less than 1% in the general population (Torgersen, 2009). Despite its low prevalence, schizotypal personality disorder is so unusual and debilitating that it is one of the most studied personality disorders (Hummelen et al., 2011). In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Illness, 5th edition (DSM-5) (APA, 2013), it is identified as a both a personality disorder and the first of the schizophrenia spectrum disorders, which are, in general, listed from least to most severe. Chapter 12 discusses the schizophrenia spectrum disorders in greater detail. Psychotic symptoms seen in persons with schizophrenia, such as hallucinations and delusions, might also exist with schizotypal personality disorder, but to a lesser degree and only briefly (Skodol et al., 2011). A major difference between this disorder and schizophrenia is that people with schizotypal personality disorder can be made aware of their misinterpretations of reality. Schizophrenia results in a far stronger grip on delusions. As a schizophrenia spectrum disorder, schizotypal personality disorder is genetically linked. There is a higher incidence of schizophrenia-related disorders in family members of people with schizotypal personality disorder. There is growing evidence to support that persons with schizotypal personality disorder have structural abnormalities of the brain such as ventricular enlargement, reductions in the volume of their striatal structures, and altered dopamine transmission mechanisms (Skodol et al., 2011). While there is no specific medication for schizotypal personality disorder, associated conditions may be treated. Persons with schizotypal personality disorders seem to benefit from low-dose antipsychotic agents for psychotic-like symptoms and day-to-day functioning (Ripoll et al., 2011). Depression and anxiety may be treated with antidepressants and antianxiety agents. Histrionic personality disorder is thought to occur at a rate of about 1.5 % in community samples (Torgersen, 2009). Persons with histrionic traits do not generally experience a reduction in quality of life. Studies focusing on heritability traits suggest there may be common risk factors for impulsivity, reduced levels of agreeableness and introversion (Skodol et al., 2001). This disorder is characterized by emotional attention-seeking behaviors, including self-centeredness, low frustration tolerance, and excessive emotionality. The person with histrionic personality disorder is often impulsive and melodramatic and may act flirtatiously or provocatively. Relationships do not last, because the partner often feels smothered or reacts to the insensitivity of the histrionic person. The individual with histrionic personality disorder does not have insight into his or her role in breaking up relationships and may seek treatment for depression or another comorbid condition. In the treatment setting, the person demands “the best of everything” and can be very critical. Narcissistic personality disorder is thought to be one of the least frequently occurring personality disorders. In the community it exists at less than 1%, but it is seen in clinical populations more frequently (Torgersen, 2009). Narcissistic personality disorder is also associated less than other personality disorders with impairment in individual functioning and the quality of one’s life. Avoidant personality disorder is fairly common and is believed to occur in about 1.7% of the U.S. population (Torgersen, 2009). The main pathological personality traits are low self-esteem that is associated with functioning in social situations, feelings of inferiority compared to peers, and a reluctance to engage in unfamiliar activities involving new people. Avoidant personality disorder has been linked with parental and peer rejection and criticism. A biological predisposition to anxiety and physiological arousal in social situations has also been suggested. Genetically, this disorder may be part of a continuum of disorders related to social anxiety disorder; studies have found a shared association between persons who have avoidant personality disorder and persons with social anxiety disorder (Skodol et al., 2011). A timid temperament in infancy and childhood may also be associated with this disorder. Persons with avoidant personality disorders seem to respond positively to antidepressant medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors like citalopram and selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors such as venlafaxine (Ripoll et al., 2011). Individual and group therapy is useful in processing anxiety-provoking symptoms and in planning methods to approach and handle anxiety-provoking situations. The prevalence rate of dependent personality disorder is about 0.7 % in community samples and has been found to be associated with moderate to low problems in functioning (Skodol et al., 2011). However, there are discrepant studies that suggest this disorder may be more common. Persons with dependent personality disorder are thought to have early and profound learning experiences during childhood in which disordered attachment and dependency on the caretaker develop. Dependent personality disorder may be the result of chronic physical illness or punishment of independent behavior in childhood. Childhood trauma has been suggested as a stress factor associated with the development of personality disorders in general and, as such, has also been found to be linked to neuroendocrine changes, both cortisol and adrenocorticotropin-releasing hormone (Birgenheir & Pepper, 2011). The inherited trait of submissiveness may also be a factor, which has been found to be 45% heritable. Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder is the most prevalent personality disorder in the general community and in clinical populations; its prevalence rate is estimated at 2.1% (Torgersen, 2009). Along with borderline personality disorder, this disorder is associated with the highest burden of medical costs, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder affects workplace productivity losses (Skodol et al., 2011). While studies vary in their estimates of prevalence depending upon methodologies, personality disorders affect about 6% of the global population (Huang et al., 2009). In the U.S. population the overall prevalence rate of personality disorders among community samples is higher—around 10% (Sansone & Sansone, 2011). Culture has a definite influence on the rate of diagnosing personality disorders. For example, Australian and North American studies reflect higher prevalence rates (Samuels, 2011). Differences may reflect personality and behavior as being viewed as deviant rather than normative in a particular culture and study methods. It is generally agreed that there are insufficient studies to address the role that ethnicity and race have on the prevalence of personality disorders (McGilloway et al., 2010). Other studies confirm that personality disorders are more common among persons who are homeless or incarcerated. Recent studies have also suggested that personality disorders affecting older adults are more common than originally thought and frequently become evident when accompanied by major depression or anxiety (Magoteaux & Bonnivier, 2009). Genetics are thought to influence the development of personality disorders (Skodol & Gunderson, 2008). Recently, studies have led to a consensus that personality disorders represent extreme variations of normal personality traits in four areas: anxious-dependency traits, psychopathy-antisocial, social withdrawal, and compulsivity (Svrakic et al., 2008). These findings support a genetic or inherited trait transmission in families. The chemical neurotransmitter theory proposes that certain neurotransmitters, including neurohormones, may regulate and influence temperament. Research in brain imaging has also revealed some differences in the size and function of specific structures of the brain in persons with some personality disorders (Coccaro & Siever, 2005). Psychoanalytic theory focuses on the use of primitive defense mechanisms by individuals with personality disorders. Defense mechanisms such as repression, suppression, regression, undoing, and splitting have been identified as dominant (Kernberg, 1985). The role of psychoanalytic theory, while historically relevant and interesting, is not confirmable through evidence-based research methods. Behavioral genetics research has shown that about half of the variance accounting for personality traits emerges from the environment (Paris, 2005). These findings suggest that while the family environment is influential on development, there are other environmental factors besides family upbringing that shape an individual’s personality. One need only think about the individual differences among siblings raised together to illustrate this point. Childhood neglect or trauma has been established as a risk factor for personality disorders (Samuels, 2011). This association has been linked to possible biological mechanisms involving corticotropin-releasing hormone in response to early life stress and emotional reactivity (Lee et al., 2011). The diathesis-stress model is a general theory that explains psychopathology using a systems approach. This theory helps us understand how personality disorders emerge from the multifaceted factors of biology and environment (Paris, 2005). Diathesis refers to genetic and biological vulnerabilities and includes personality traits and temperament. Temperament is our tendency to respond to challenges in predictable ways. Descriptors of temperament may be “laid back,” referring to a calm temperament, or “uptight,” as an example of an anxious temperament. These characteristics remain stable throughout a person’s life. In this model, stress refers to immediate influences on personality, such as the physical, social, psychological, and emotional environment. Stress also includes what happened in the past, such as growing up in one’s family with exposure to unique experiences and patterns of interaction. Under conditions of stress, the diathesis-stress model proposes that personality development becomes maladaptive for some people, resulting in the emergence of a personality disorder (Paris, 2005). Table 24-2 provides an overview of nursing and other therapies for the treatment of all the personality disorders discussed above. Two additional personality disorders, antisocial and borderline, are included in this table for a quick reference, and they are also addressed in more depth in the remainder of the chapter. TABLE 24-2 NURSING AND THERAPY GUIDELINES FOR PERSONALITY DISORDERS

Personality disorders

Clinical picture

PERSONALITY DISORDER

TOTAL POPULATION

GENDER

COMORBIDITY

Avoidant

1.7%

Equal in men and women

Mood disorders

Anxiety disorders

Antisocial

1.1%

More men

Anxiety disorders

Depressive disorders

Substance use disorders

Somatization disorders

Borderline

1.6%

More women

Mood disorders

Substance use disorders

Eating disorders

Posttraumatic stress disorders

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Dependent

0.7%

More women

Mood disorders

Anxiety disorders

Adjustment disorders

Histrionic

1.5%

More women

Major depressive disorder

Somatization disorder

Conversion disorder

Narcissistic

<1%

More women

Depressive disorders

Substance use disorders

Anorexia nervosa

Paranoid

1.7%

More men

Major depressive disorder

Agoraphobia

Obsessive-compulsive disorders

Substance abuse disorders

Obsessive-compulsive

2.1%

More men

Anxiety disorders

Mood disorders

Eating disorders

Schizoid

0.9%

More men

Major depressive disorder

Schizotypal

<1%

More men

Major depressive disorder

Paranoid personality disorder

Schizoid personality disorder

Schizotypal personality disorder

Histrionic personality disorder

Narcissistic personality disorder

Avoidant personality disorder

Dependent personality disorder

Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder

Epidemiology and comorbidity

Etiology

Biological factors

Genetic

Neurobiological

Psychological factors

Environmental factors

Diathesis-stress model