inflammation, or recent trauma with possible hidden fractures or internal injuries.

Before attempting a transfer, review the principles of body mechanics. Consider using additional staff when transferring heavier patients.

Before attempting a transfer, review the principles of body mechanics. Consider using additional staff when transferring heavier patients.wheels are also locked and that the bed is in its lowest position.

and bear as much weight as possible on the unaffected side. Support the affected side because the patient will tend to lean to this side. To prevent slumping in the wheelchair, use pillows to support a hemiplegic patient’s affected side.

than making one step long and slow and the other short and quick.

POSITION | INDICATIONS | IMPLEMENTATION | RATIONALE |

Dorsal recumbent (supine) | ♦ Spinal cord injury ♦ Urinary catheter insertion ♦ Vaginal examination | ♦ Place the patient on his back with the knees slightly flexed. ♦ Place a pillow beneath his head for comfort. | ♦ Immobilizes the spine |

Trendelenburg’s | ♦ Cystic fibrosis | ♦ Position the patient in a supine position with his feet elevated 30 to 40 degrees higher than his head. | ♦ Promotes postural drainage and venous return |

Reverse Trendelenburg’s | ♦ Cervical traction ♦ Post lower extremity-vessel surgery | ♦ Elevate the head of the bed and lower the feet. | ♦ Provides counterbalance for traction ♦ Promotes blood flow to the lower extremities |

Prone | ♦ Immobilization ♦ Acute respiratory distress syndrome ♦ Post lumbar puncture or myelogram | ♦ Place the patient on his stomach with the head turned to one side. ♦ Position the arms at the side or above the head. ♦ Make sure that the legs are extended. | ♦ Enables examination of the back and spine ♦ Promotes gas exchange |

Lateral (side-lying) | ♦ Post abdominal surgery ♦ Coma ♦ Pressure ulcer ♦ Enema or rectal irrigation | ♦ Place the patient on his side, with his weight being mostly supported by the lateral aspect of the lower scapula and the lower ileum. ♦ Support with pillows. ♦ Promotes safety ♦ Prevents atelectasis, pressure ulcers, and aspiration of food and secretions | |

Sims’ | ♦ Coma ♦ Rectal injuries | ♦ Position the patient on his side with a small pillow beneath his head. ♦ Flex one knee toward the abdomen, with the other knee only slightly flexed. ♦ Place one arm behind the body and the other in a comfortable position. Support with pillows. | ♦ Enables examination of the back and rectum ♦ Prevents pressure ulcers and atelectasis |

Elevation of extremity | ♦ Thrombophlebitis ♦ Post cast application ♦ Edema ♦ Post surgery on limb | ♦ Use the bed controls to elevate the legs, or use pillows to elevate the arms and legs. | ♦ Promotes circulation and comfort ♦ Enables examinations and procedures |

Fowler’s | ♦ Head injury, cranial surgery, increased intracranial pressure (ICP) ♦ Post abdominal surgery ♦ Dyspnea ♦ Vomiting ♦ Post thyroidectomy ♦ Post eye surgery | ♦ Elevate the head of the bed to 45 degrees and raise the bed section under the patient’s knees, flexing the knees slightly. | ♦ Enables examination ♦ Immobilizes the spine ♦ Promotes drainage, cardiac output, and ventilation ♦ Prevents aspiration of food and secretions |

Semi-Fowler’s | ♦ Head injury, cranial surgery, increased ICP ♦ Post abdominal surgery ♦ Dyspnea ♦ Vomiting ♦ Post thyroidectomy ♦ Post eye surgery ♦ Ventilated patients | ♦ Elevate the head of the bed to 30 degrees and raise the bed section under the patient’s knees, flexing the knee slightly. | ♦ Promotes drainage, cardiac output, and ventilation ♦ Prevents aspiration of food and secretions ♦ Helps prevent ventilation-associated pneumonia |

High Fowler’s | ♦ Head injury, cranial surgery ♦ Dyspnea, respiratory distress ♦ Feeding (during and after meals) ♦ Hiatal hernia | ♦ Elevate the head of the bed to 90 degrees and raise the bed section under the patient’s knees, flexing the knees slightly. | ♦ Promotes drainage, cardiac output, and ventilation ♦ Prevents aspiration of food and secretions |

Lithotomy | ♦ Perineal or rectal procedure | ♦ Place the patient on his back (either flat or with the head slightly elevated). ♦ Knees should be flexed at right angles and feet placed in stirrups. | ♦ Enables examination of the pelvis |

|

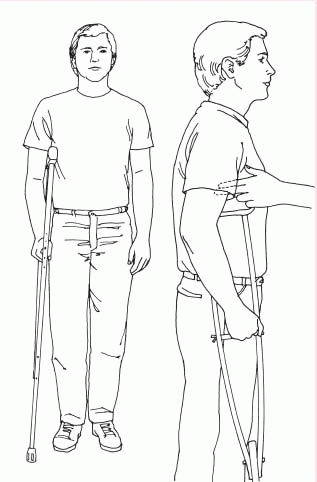

step up with the strong leg while supporting his weight with both crutches and the weak leg on the lower step. Then he can move the crutches and weak leg up.