Common procedures

Adult CPR

♦ Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is used to restore and maintain the patient’s respiration and circulation after the heartbeat and breathing have stopped.

♦ CPR is a basic life support (BLS) procedure performed on patients in cardiac arrest.

♦ Most adults in sudden cardiac arrest develop ventricular fibrillation and require defibrillation.

♦ CPR alone doesn’t improve the chances of survival in adults requiring defibrillation.

♦ Assess the patient, then contact emergency medical services (EMS) or call a code before starting CPR.

♦ It’s generally performed to keep the patient alive until advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) can begin.

♦ Basic CPR procedure consists of assessing the patient, calling for help, and then following the ABC protocol: opening the airway, restoring breathing, and restoring circulation.

♦ Timing is critical; early access to EMS, early CPR, and early defibrillation greatly improve survival chances.

♦ After the airway has been opened and breathing and circulation are restored, drug therapy, diagnosis by electrocardiogram, or defibrillation may follow.

♦ If possible, find out if the patient has a Do Not Resuscitate order before beginning CPR.

Equipment

A hard surface on which to place the patient ♦ protective equipment, such as a disposable airway device (optional)

Implementation

♦ These instructions provide a step-by-step guide for CPR as currently recommended by the American Heart Association (AHA).

One-person rescue

♦ If you’re the sole rescuer, determine unresponsiveness, call for help, open the patient’s airway, check for breathing, give rescue breaths, assess for circulation, and begin compressions.

♦ Assess the patient to determine if he’s unconscious.

♦ To ensure you don’t start CPR on a person who’s conscious, shake his shoulders and shout, “Are you okay?”

♦ If there’s no response, check whether the patient has an injury, particularly to the head or neck.

If you suspect a head or neck injury, move the patient as little as possible to reduce risk of paralysis.

If you suspect a head or neck injury, move the patient as little as possible to reduce risk of paralysis.♦ Call out for help, send someone to contact EMS or call a code, as appropriate.

♦ Put the patient in the supine position on a hard, flat surface.

♦ When moving the patient, roll his head and torso as a unit. Avoid twisting or pulling his neck, shoulders, or hips.

♦ Kneel near the patient’s shoulders to gain easy access to his head and chest.

♦ Usually, the muscles controlling the patient’s tongue will be relaxed, causing the tongue to obstruct the airway.

Open the airway: head-tilt, chin-lift maneuver

♦ If the patient doesn’t appear to have a neck injury, use the head-tilt, chinlift maneuver to open his airway.

♦ To open the patient’s airway, place one hand on his forehead and apply pressure to tilt his head back.

♦ Place the fingertips of your other hand under the bony part of his lower jaw near his chin.

♦ Lift his chin while keeping his mouth partially open.

♦ Avoid placing your fingertips on the soft tissue under his chin because this maneuver may obstruct the airway.

Open the airway: jaw-thrust maneuver

♦ If you suspect a neck injury, use the jaw-thrust maneuver instead of the head-tilt, chin-lift maneuver.

♦ Kneel at the patient’s head with your elbows on the ground.

♦ Rest your thumbs on the patient’s lower jaw near the corners of the mouth, pointing your thumbs toward his feet.

♦ Place your fingertips around the lower jaw.

♦ To open the airway, lift the lower jaw with your fingertips.

Check for breathing

♦ While maintaining the open airway, place your ear over his mouth and nose.

♦ Listen for air moving and note whether his chest rises and falls.

♦ You may also feel for airflow on your cheek.

♦ If he starts to breathe, keep the airway open and continue checking breathing until help arrives.

♦ If he doesn’t start breathing after you open his airway, begin rescue breathing.

♦ Pinch his nostrils shut using the hand you had on his forehead.

♦ Take a regular (not deep) breath and place your mouth over his, creating a tight seal.

♦ Give two full breaths that make his chest rise (each ventilation should last over 1 second).

♦ If ventilation isn’t successful, reposition his head and try again.

♦ If you aren’t successful, check for dentures or another foreign-body airway obstruction and follow the procedure for clearing obstruction.

Assess circulation

♦ Keep your hand on his forehead so the airway remains open.

♦ Palpate the carotid artery closer to you with your other hand.

♦ Place your index and middle fingers in the groove between the trachea and the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

♦ Palpate for 10 seconds and observe for signs of circulation (skin color and warmth).

If you detect a pulse, don’t start chest compressions. Instead, do rescue breathing, giving 10 to 12 breaths (one every 5 to 6 seconds). After 2 minutes, recheck the pulse. Each breath should be given over 1 second and cause a visible chest rise. After 2 minutes, recheck the pulse but spend only 10 seconds doing so.

If you detect a pulse, don’t start chest compressions. Instead, do rescue breathing, giving 10 to 12 breaths (one every 5 to 6 seconds). After 2 minutes, recheck the pulse. Each breath should be given over 1 second and cause a visible chest rise. After 2 minutes, recheck the pulse but spend only 10 seconds doing so.♦ If there’s no pulse, start giving chest compressions.

♦ Make sure the patient is lying on a hard surface.

♦ Make sure your knees are apart for a wide base of support.

♦ Put the heel of your other hand on the center of his chest at the nipple line.

♦ Place the other hand directly on top of the first hand, making sure your fingers aren’t on his chest. This position will keep the compression force on the sternum and reduce the risk of rib fracture, lung puncture, or liver laceration.

♦ With elbows locked, arms straight, and shoulders directly over your hands, you’re ready to give chest compressions.

♦ Compress the patient’s sternum 1½″ to 2″ (4 to 5 cm) using your

upper body weight; deliver pressure through the heels of your hands.

upper body weight; deliver pressure through the heels of your hands.

♦ After each compression, release pressure completely and allow the chest to return to a normal position so the heart can fill with blood.

♦ Give 30 chest compressions at a rate of about 100 per minute. Push hard and fast.

♦ Open the airway and give two ventilations. Find the proper hand position again and give 30 more compressions.

♦ Continue chest compressions until EMS arrives or another rescuer arrives with the automated external defibrillator (AED).

♦ Health care professionals should interrupt chest compressions as infrequently as possible. Interruptions should last no longer than 10 seconds except for special interventions, such as use of an AED or insertion of an airway.

Two-person rescue

♦ If another rescuer arrives, and the EMS team hasn’t arrived, tell the second rescuer to repeat the call for help.

♦ If the second rescuer isn’t a health care professional, ask him to stand by. Then, after about 2 minutes or five cycles of compressions and ventilations, you could switch. The switch should occur within 5 seconds.

♦ If the rescuer is another health care professional, you can perform twoperson CPR. He should start assisting after you’ve finished five cycles of 30 compressions, two ventilations, and a pulse check.

♦ The second rescuer should be opposite you.

♦ While you’re checking for a pulse, he should find the proper hand placement for delivering chest compressions.

♦ If you don’t detect a pulse, say, “No pulse, continue CPR.”

♦ The second rescuer should begin giving compressions at a rate of 100 per minute.

♦ Compressions and ventilations should be given at a ratio of 30 to 2.

♦ The “compressor” should count out loud so that the “ventilator” can anticipate when to ventilate.

♦ To ensure ventilations are effective, they should cause a visible chest rise.

♦ As the “ventilator,” you must check for breathing and a pulse.

♦ The compressor role should switch after five cycles of compressions and ventilations. The switch should take no more than 5 seconds.

♦ Both rescuers should continue giving CPR until an AED or defibrillator arrives, the ACLS providers take over, or the victim starts to move.

Special considerations

♦ Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) isn’t known to be transmitted in saliva, but some health care professionals may hesitate to give rescue breaths if the patient has AIDS. AHA recommends health care professionals learn how to use disposable airway equipment.

Documentation

♦ Note why you initiated CPR; report whether the patient suffered cardiac or respiratory arrest.

♦ Record when you found the patient and started CPR and how long the patient received CPR.

♦ Note the patient’s response and complications.

♦ Document if the patient was moved to the intensive care area.

♦ Document health care personnel participating in the resuscitation.

Adult obstructed airway

♦ Obstructed airway can occur when a foreign body lodges in the throat or bronchus; when the patient aspirates blood, mucus, or vomitus; when the tongue blocks the pharynx; or when the patient experiences traumatic injury, bronchoconstriction, or bronchospasm.

♦ The patient will display such symptoms as grabbing his throat with his hand, inability to speak, weak and ineffective coughing, or high-pitched sounds while inhaling.

♦ Airway obstruction causes anoxia, which leads to brain damage and death in 4 to 6 minutes.

♦ If the patient is unconscious, an abdominal thrust should be used.

♦ For pregnant patients, markedly obese patients, and patients who have recently undergone abdominal surgery, a chest thrust should be used.

Equipment

No specific equipment needed

Implementation

♦ Determine the patient’s level of consciousness by shouting, “Are you choking? Can you speak?”

♦ Assess for airway obstruction.

♦ Don’t intervene if the person is coughing forcefully and able to speak; a strong cough can dislodge the object.

♦ Give each individual thrust with the intent of relieving the obstructing object. It may be necessary to repeat thrusts to dislodge the obstruction and clear the airway.

Conscious adult

♦ Tell the patient that you’ll try to dislodge the foreign body.

♦ Stand behind him, and wrap your arms around his waist.

♦ Make a fist with one hand, and place the thumb side of your fist against his abdomen, in the midline, slightly above the umbilicus and well below the xiphoid process.

♦ Grasp your fist with the other hand.

♦ Press your fist into the victim’s abdomen with quick inward and upward thrusts.

♦ Each thrust should be a separate and distinct movement; each should be forceful enough to create an artificial cough that will dislodge the object.

♦ Repeat thrusts until the object is expelled from the airway or the victim becomes unresponsive.

♦ Make sure you have a firm grasp on the patient because he may lose consciousness and need to be lowered to the floor.

♦ If the patient loses consciousness, lower him to the floor, support his head and neck to prevent injury, and place him supine.

♦ Call for help, activate the emergency response system, and begin cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

♦ Open the airway with the tonguejaw lift, perform a finger-sweep only if you can see the object, and attempt to ventilate.

♦ If the chest doesn’t rise, reposition the airway and attempt to ventilate again.

♦ If ventilation is unsuccessful, begin CPR.

Unconscious adult

♦ Establish unresponsiveness. Call for help, and activate the emergency response system.

♦ Open the airway (head tilt-chin lift or jaw-thrust) and check for breathing; if not breathing, attempt to ventilate.

Each time you open the airway to give breaths, open the victim’s mouth wide and look for the object. If you see the object, remove it with your fingers. If you do not see the object, continue CPR.

Each time you open the airway to give breaths, open the victim’s mouth wide and look for the object. If you see the object, remove it with your fingers. If you do not see the object, continue CPR.♦ If you’re unable to ventilate him, reposition his head and try again.

♦ Lift the jaw to draw the tongue away from the back of the throat and away from any foreign body.

♦ If you can see the object, remove it by inserting your index finger and perform a sweeping motion to remove the obstruction.

♦ You can assess if you have successfully removed the object in the unresponsive victim if you feel air movement and see the chest rise when you give breaths or if you see and remove the foreign body from the victim’s pharynx.

♦ After the object is removed, try to ventilate the patient.

♦ Assess for spontaneous respirations, and check for a pulse.

♦ Proceed with CPR if necessary.

Conscious obese or pregnant adult

♦ Stand behind the patient, and place your arms under the armpits and around the chest.

♦ Place the thumb side of your clenched fist against the middle of the sternum, avoiding the margins of the ribs and the xiphoid process.

♦ Grasp your fist with your other hand, and perform a chest thrust with enough force to expel the foreign body.

♦ Continue until the patient expels the obstruction or loses consciousness.

♦ If the patient loses consciousness, lower him to the floor, support his head and neck to prevent injury, and place him supine.

♦ Call for help, activate the emergency response system, and begin CPR.

♦ Open the airway with the tonguejaw lift, perform a finger-sweep only if you can see the object, and attempt to ventilate.

♦ If the chest doesn’t rise, reposition the airway and attempt to ventilate again.

♦ If ventilation is unsuccessful, begin CPR.

Unconscious obese or pregnant adult

♦ Establish unresponsiveness.

♦ Call for help and activate the emergency response system.

♦ Open the airway with the tonguejaw lift, perform a finger-sweep, and attempt to ventilate.

♦ If the chest doesn’t rise, reposition the airway and attempt to ventilate again.

♦ If ventilation is unsuccessful, begin CPR.

Special considerations

♦ If the patient vomits, wipe out his mouth to prevent additional obstruction.

♦ Even if efforts to clear the airway don’t seem to be effective, keep trying.

♦ Explain what you’re doing to gain the patient’s cooperation, as needed.

Documentation

♦ Record the date and time of the event.

♦ Note the patient’s actions before the obstruction.

♦ Document the approximate length of time it took to clear the airway.

♦ Record the type and size of object removed.

♦ Note vital signs after the event.

♦ Document complications and nursing actions taken.

Bladder irrigation, continuous

♦ Continuous bladder irrigation is used to flush small blood clots that form after prostate or bladder surgery, and it may be used to dissolve certain bladder calculi or treat an irritated, inflamed, or infected bladder lining.

♦ The continuous flow of irrigating solution through the bladder also creates a mild tamponade that may help prevent venous hemorrhage.

♦ The catheter may be inserted in the operating room after surgery, or it may be inserted at the bedside in nonsurgical patients.

♦ The procedure requires placement of a triple-lumen catheter.

♦ One lumen controls balloon inflation, one allows irrigant inflow, and one allows irrigant outflow.

Equipment

One 4,000-ml container or two 2,000-ml containers of irrigating solution (usually normal saline solution) or the prescribed amount of medicated solution ♦ Y-type tubing made specifically for bladder irrigation ♦ alcohol ♦ I.V. pole or bedside pole attachment ♦ drainage bag and tubing

Implementation

♦ Double-check the irrigating solution against the physician’s order. Usually, normal saline solution is prescribed for bladder irrigation after prostate or bladder surgery. The patient will need large volumes of solution for the first 24 to 48 hours after surgery. Make sure the solution is at room temperature or slightly warmed for patient comfort.

♦ If the solution contains an antibiotic, check the patient’s chart to make sure he isn’t allergic to the drug.

♦ Wash your hands. Assemble all equipment at the patient’s bedside. Explain the procedure and provide privacy.

♦ Hang the irrigating solution on the I.V. pole.

♦ Insert one spike of the Y-type tubing into each container of irrigating solution.

♦ Unclamp the tubing clamp on one container of irrigation solution. Squeeze the drip chamber on the tubing.

♦ Open the flow clamp and flush the tubing to remove air, which could cause bladder distention. Then close the clamp.

♦ Clean the opening to the inflow lumen (third port) of the catheter with alcohol.

♦ Insert the distal end of the Y-type tubing securely into the inflow lumen of the catheter.

♦ Make sure that the outflow lumen is securely attached to the tubing of the drainage bag.

♦ Open the flow clamp and set the drip rate as ordered.

♦ To prevent air from entering the system, replace the primary container before it empties completely.

♦ If you have a two-container system, simultaneously close the clamp under the nearly empty container and open the clamp under the reserve container. This prevents reflux of irrigating solution from the reserve container into the nearly empty one. Hang a new reserve container on the I.V. pole and insert the tubing, maintaining asepsis.

♦ Empty the drainage bag about every 4 hours or as often as needed. Use sterile technique to avoid the risk of contamination.

♦ Monitor the patient’s vital signs at least every 4 hours during irrigation. Increase the frequency of monitoring if the patient’s condition becomes unstable.

Special considerations

♦ Unless specified otherwise, the patient should remain on bed rest while receiving continuous bladder irrigation.

♦ Check the inflow and outflow lines periodically for kinks to make sure the solution is running freely. If the solution flows rapidly, check the lines often.

♦ Measure the outflow volume accurately. It should, allowing for urine production, exceed inflow volume.

If the inflow volume exceeds the outflow volume postoperatively, suspect bladder rupture at the suture lines or renal damage, and notify the physician immediately.

If the inflow volume exceeds the outflow volume postoperatively, suspect bladder rupture at the suture lines or renal damage, and notify the physician immediately.♦ Check outflow for changes in appearance and for blood clots, especially if irrigation is ordered postoperatively to control bleeding.

– If the drainage is bright red, irrigating solution is usually infused rapidly, with the clamp wide open, until the drainage clears. Notify the physician at once if you suspect hemorrhage.

– If the drainage is clear, the solution is usually given at a rate of 40 to 60 gtt/minute. The physician typically specifies the rate for antibiotic solutions.

♦ Encourage oral fluid intake of 2 to 3 qt/day (2 to 3 L/day), unless contraindicated by another medical condition.

♦ Watch for interruptions in the continuous irrigation system; these can predispose the patient to infection.

♦ Check often for obstruction in the outflow lumen of the catheter. Obstruction can lead to bladder distention and rupture.

Documentation

♦ Record the date, time, and amount of fluid given (on the intake and output record) each time you finish a container of solution.

♦ Record the time and amount of fluid each time you empty the drainage bag.

♦ Note the appearance of drainage.

♦ Note any patient complaints.

Blood glucose monitoring

♦ Two major processes permit nonlaboratory measurement of blood glucose.

– In color reflectance photometry, a reagent patch on the tip of a handheld plastic strip changes color in response to the amount of glucose in the blood sample. Comparing the color change with a standardized color chart provides a semiquantitative measurement of blood glucose levels. The strip may also be inserted in a portable blood glucose meter to provide quantitative measurements that compare in accuracy with laboratory tests.

– In biosensor or electrochemical testing, an electrical charge that is proportional to the blood glucose content is created. A plastic strip containing a small blood sample on a marked membrane is inserted into the meter and read in 5 to 45 seconds.

♦ Both metering systems provide accurate results when used as directed. Capillary blood samples can be obtained from a fingerstick, heelstick or earlobe, and some newer models also accept samples from the palm, forearm, or thigh.

♦ These tests can monitor abnormal blood glucose levels in patients with diabetes, screen for diabetes mellitus and neonatal hypoglycemia, and help distinguish diabetic coma from nondiabetic coma.

♦ The tests can be performed anywhere.

♦ Specialized machines have been designed for low vision users, users with poor manual dexterity, and users who wish to record and store large amounts of related information, such as diet, for later retrieval.

Equipment

Reagent strips ♦ gloves ♦ portable blood glucose meter ♦ alcohol pads ♦ gauze pads ♦ disposable lancets or mechanical blood-letting device ♦ small adhesive bandage ♦ watch or clock with a second hand, if meter is unavailable

Implementation

♦ Verify the patient’s identity using two patient identifiers. Explain the procedure to the patient. If the patient is a child, explain the procedure to the parents and child. Provide privacy.

♦ Select the puncture site; this is usually the lateral side of a fingertip but may also be the arm or leg, depending on the machine used.

Select the heel or great toe for an infant.

♦ Wash your hands and put on gloves.

♦ If needed, dilate the capillaries by applying warm, moist compresses to the area for about 10 minutes or place the limb in a dependent position below the heart.

♦ Wipe the puncture site with an alcohol pad, and dry it thoroughly with a gauze pad.

♦ To collect a sample from the fingertip with a disposable lancet (smaller than 2 mm) or an Autolet (which uses a spring-loaded lancet), position the lancet on the side of the patient’s fingertip, perpendicular to the fingerprint lines. Pierce the skin sharply and quickly to minimize the patient’s pain and anxiety and to increase blood flow.

♦ After puncturing the fingertip, don’t squeeze the puncture site to avoid diluting the sample with tissue fluid.

♦ Touch a drop of blood to the reagent patch or membrane on the strip; make sure you cover the entire area.

♦ After collecting the blood sample, briefly apply pressure to the puncture site to prevent painful extravasation of blood into subcutaneous tissues. Ask an adult patient to hold a gauze pad firmly over the puncture site until bleeding stops.

♦ If reading the test without a meter, leave the blood on the reagent strip for exactly 60 seconds. Compare the color change on the strip with the standardized color chart on the product container.

♦ If you’re using a blood glucose meter, follow the manufacturer’s instructions and read the result on the digital display.

♦ After bleeding has stopped, you may apply a small adhesive bandage to the puncture site, if needed.

Special considerations

♦ Before using reagent strips, check the expiration date on the package, and replace outdated strips. Check for special instructions related to the specific reagent. The reagent area of a fresh strip should match the color of the “0” block on the color chart. Protect the strips from light, heat, and moisture.

♦ Before using a blood glucose meter, calibrate it and run it with a control sample to ensure accurate test results. Follow the manufacturer’s instructions for calibration.

♦ Avoid selecting cold, cyanotic, or swollen puncture sites to ensure an adequate blood sample. If you can’t obtain a capillary sample, perform venipuncture and place a large drop of venous blood on the reagent strip. If you

want to test blood from a refrigerated sample, allow the blood to return to room temperature before testing it.

want to test blood from a refrigerated sample, allow the blood to return to room temperature before testing it.

♦ To help detect abnormal glucose metabolism and diagnose diabetes mellitus, the physician may order other blood glucose tests.

Documentation

♦ Record the reading from the reagent strip or blood glucose meter (in your notes or on a special flowchart, if available).

♦ Document the time and date of the test.

♦ Record how the patient tolerated the procedure and any teaching done.

Chest physiotherapy

♦ Chest physiotherapy (PT) includes postural drainage, coughing and deepbreathing exercises, and chest percussion and vibration.

♦ Together, these techniques mobilize and eliminate secretions, reexpand lung tissue, and promote efficient use of the respiratory muscles.

♦ Chest PT is critically important for bedridden patients by helping to prevent or treat atelectasis and pneumonia, two potentially serious respiratory complications.

♦ Postural drainage performed with percussion and vibration encourages peripheral pulmonary secretions to empty by gravity into the major bronchi or trachea and is accomplished by sequential repositioning of the patient.

– Usually, secretions drain best with the patient positioned with the bronchi perpendicular to the floor.

– Lower- and middle-lobe bronchi usually empty best with the patient in the head-down position; upper-lobe bronchi, in the head-up position.

♦ Percussing the chest with cupped hands mechanically dislodges thick, tenacious secretions from the bronchial walls.

♦ Vibration can be used with or instead of percussion in a patient who’s frail, in pain, or recovering from thoracic surgery or trauma.

♦ Candidates for chest PT include patients who expectorate large amounts of sputum, such as those with bronchiectasis or cystic fibrosis.

♦ The procedure hasn’t proved effective in treating patients with status asthmaticus, lobar pneumonia, or acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis when the patient has scant secretions and is being mechanically ventilated. It also has little value for patients with stable, chronic bronchitis.

♦ Contraindications include active pulmonary bleeding with hemoptysis, the immediate posthemorrhage stage, fractured ribs, an unstable chest wall, lung contusions, pulmonary tuberculosis, untreated pneumothorax, acute asthma or bronchospasm, lung abscess or tumor, bony metastasis, head or neck injury, and recent myocardial infarction.

Equipment

Stethoscope ♦ emesis basin ♦ facial tissues ♦ suction equipment as needed ♦ equipment for oral care ♦ trash bag

Implementation

♦ Gather the equipment at the bedside. Set up suction equipment, if needed, and test its function.

♦ Explain the procedure to the patient, provide privacy, and wash your hands.

♦ Auscultate the patient’s lungs with a stethoscope to evaluate the patient’s baseline respiratory status.

Performing percussion and vibration

To perform percussion, instruct the patient to breathe slowly and deeply, using the diaphragm, to promote relaxation. Hold your hands in a cupped shape, with your fingers flexed and your thumbs pressed tightly against your index fingers. Percuss each segment for 1 to 2 minutes by alternating your hands against the patient in a rhythmic manner. Listen for a hollow sound on percussion to verify that you’re performing the technique correctly.

|

To perform vibration, ask the patient to inhale deeply and then to exhale slowly through pursed lips. While the patient exhales, firmly press your fingers and the palms of your hands against the chest wall. Tense the muscles of your arms and shoulders in an isometric contraction to send fine vibrations through the chest wall. Vibrate during five exhalations over each chest segment.

|

♦ Position the patient as needed using pillows.

– For patients with generalized disease, drainage usually starts with the lower lobes, continues with the middle lobes, and ends with the upper lobes.

– For patients with localized disease, drainage starts with the affected lobes and proceeds to the other lobes to avoid spreading the disease to uninvolved areas.

♦ Instruct the patient to remain in each position for 10 to 15 minutes. During this time, perform percussion and vibration as ordered. (See Performing percussion and vibration.)

♦ After you perform postural drainage, percussion, or vibration, instruct the patient to cough to remove loosened secretions.

– Tell him to inhale deeply through his nose and then to exhale in three short huffs.

– Instruct him to inhale deeply again and then to cough through a slightly open mouth.

– Three consecutive coughs are highly effective.

– An effective cough sounds deep, low, and hollow; an ineffective one, high-pitched.

♦ Have the patient exercise for about 1 minute, then have him rest for 2 minutes. Gradually progress to 10-minute exercise periods done four times daily.

♦ Provide oral hygiene because secretions may have a foul taste or a stale odor.

♦ Dispose of secretions with suction equipment or tissues and a trash bag.

♦ Provide an emesis basin if needed.

♦ Auscultate the patient’s lungs to evaluate the effectiveness of therapy.

Special considerations

♦ For optimal effectiveness and safety, modify chest PT according to the patient’s condition.

– For example, start or increase the flow of supplemental oxygen, if indicated.

– Also, suction a patient who has an ineffective cough reflex.

– If the patient tires quickly during therapy, shorten the sessions. Fatigue leads to shallow respirations and increased hypoxia.

♦ Chest PT should be limited to 30 minutes or less, as tolerated. Drainage of different lobes may need to be done during separate PT sessions.

♦ If the patient is receiving chest PT to prevent dehydration of mucus and promote easier mobilization, make sure he takes in plenty of fluids.

♦ Avoid performing postural drainage immediately before or within 1½ hours after meals to avoid nausea and aspiration of food or vomitus.

♦ Because chest percussion can induce bronchospasm, adjunct treatment (for example, intermittent positivepressure breathing, aerosol, or nebulizer therapy) should precede chest PT.

♦ To avoid injuring the spine or internal organs, don’t percuss over the spine, liver, kidneys, or spleen. Also, don’t percuss over bare skin or a woman’s breasts. Percuss over soft clothing (but not over buttons, snaps, or zippers), or place a thin towel over the chest wall. Remove jewelry that might scratch or bruise the patient.

♦ Observe the patient for complications.

– During postural drainage in headdown positions, pressure on the diaphragm by abdominal contents can impair respiratory excursion and lead to hypoxia or orthostatic hypotension.

– The head-down position may also lead to increased intracranial pressure, which precludes the use of chest PT in a patient with acute neurologic impairment.

– Vigorous percussion or vibration can cause rib fracture, especially if the patient has osteoporosis.

– In a patient with emphysema and blebs, coughing can lead to pneumothorax.

Documentation

♦ Record the date and time of chest PT.

♦ Note positions used to drain secretions.

♦ Record the length of time each position maintained.

♦ Note the chest segments percussed or vibrated.

♦ Record color, amount, odor, and viscosity of secretions produced.

♦ Note any presence of blood.

♦ Note complications and nursing actions taken.

♦ Note patient’s tolerance of treatment.

Colostomy and ileostomy care

♦ A patient with an ascending or transverse colostomy or an ileostomy must wear an external pouch to collect

emerging fecal matter, which is typically watery or pasty.

emerging fecal matter, which is typically watery or pasty.

♦ Besides collecting waste matter, the pouch helps to control odor and protect the stoma and peristomal skin.

♦ All pouching systems must be changed immediately if a leak develops, and every pouch must be emptied when it’s one-third to one-half full. The patient with an ileostomy may need to empty his pouch four or five times daily.

♦ The best time to change the pouching system is when the bowel is least active, usually 2 to 4 hours after meals.

♦ After a few months, most patients can predict their best changing time.

♦ Most disposable pouching systems can be used for 2 to 7 days; some models last even longer.

♦ The selection of a pouching system should take into consideration which system provides the best adhesive seal and skin protection for the individual patient.

♦ The type of pouch selected also depends on the location and structure of the stoma, the availability of supplies, the wear time, the consistency of effluent, personal preference, and cost.

♦ Pouching systems may be drainable or closed-bottomed, disposable or reusable, adhesive-backed, and one- or two-piece. (See Comparing ostomy pouching systems.)

Equipment

Pouching system ♦ stoma measuring guide ♦ stoma paste (if drainage is watery to pasty or stoma secretes excess mucus) ♦ scissors ♦ water ♦ closure clamp ♦ toilet or bedpan ♦ gloves ♦ facial tissue ♦ prepared skin barrier ♦ gauze pad ♦ optional: ostomy belt, paper tape, mild nonmoisturizing soap, skin shaving equipment

Implementation

♦ Explain the procedure to the patient.

♦ Provide privacy and emotional support.

♦ Gather the equipment and take it to the patient’s bedside.

Fitting the pouch and skin barrier

♦ For a pouch with an attached skin barrier, measure the stoma with the stoma-measuring guide. Select the opening size that matches the stoma.

♦ For an adhesive-backed pouch with a separate skin barrier, measure the stoma with the measuring guide and select the opening that matches the stoma.

– Trace the selected size opening onto the paper back of the skin barrier.

– Cut out the opening.

– If the pouch has precut openings, which can be handy for a round stoma, select an opening that’s 1/8 ″ (3 mm) larger than the stoma. If the pouch comes without an opening, cut the hole 1/8 ″ wider than the measured tracing.

– The cut-to-fit system works best for an irregularly shaped stoma.

♦ For a two-piece pouching system with flanges, follow the instructions shown in Applying a skin barrier and pouch, page 252.

♦ Avoid fitting the pouch too tightly because the stoma has no pain receptors. A constrictive opening could injure the stoma or the skin without the patient feeling discomfort.

♦ Avoid cutting the opening too big because a large opening may expose the skin to fecal matter and moisture.

♦ A patient with a descending or sigmoid colostomy who has formed stools and whose ostomy doesn’t secrete much mucus may choose to wear only a pouch. In this case, make sure that

the pouch opening closely matches the stoma size.

the pouch opening closely matches the stoma size.

Comparing ostomy pouching systems

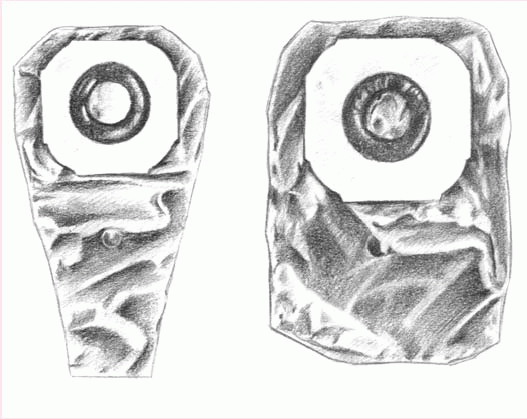

Manufactured in many shapes and sizes, ostomy pouches are fashioned for comfort, safety, and easy application. For example, a disposable, closed-end pouch may meet the needs of a patient who irrigates, who wants added security, or who wants to discard the pouch after each bowel movement. Another patient may prefer a reusable, drainable pouch. Some commonly available pouches are described here.

Disposable pouches

The patient who must empty his pouch often (because of diarrhea or a new colostomy or ileostomy) may prefer a one-piece, drainable, disposable pouch with a closure clamp attached to a skin barrier (below left).

These transparent or opaque, odorproof, plastic pouches come with attached adhesive or karaya seals. Some pouches have microporous adhesive or belt tabs. The bottom opening allows for easy draining. This pouch may be used permanently or temporarily, until the stoma size stabilizes.

Also disposable and made of transparent or opaque, odor-proof plastic, a onepiece, disposable, closed-end pouch (below right) may come in a kit with an adhesive seal, belt tabs, a skin barrier, or a carbon filter for gas release. A patient with a regular bowel elimination pattern may choose this style for added security and confidence.

|

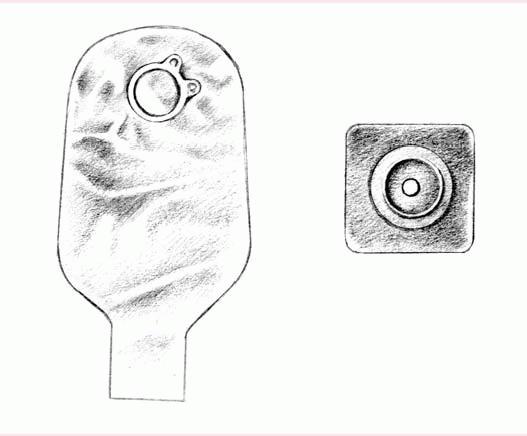

A two-piece, disposable, drainable pouch with a separate skin barrier (shown below) permits frequent changes and minimizes skin breakdown. Also made of transparent or opaque, odorproof plastic, this style comes with belt tabs and usually snaps to the skin barrier with a flange mechanism.

|

Reusable pouches

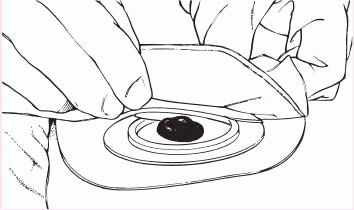

Typically manufactured from sturdy, opaque, hypoallergenic plastic, the reusable pouch comes with a separate, custom-made faceplate and O-ring (as shown below). Some pouches have a pressure valve for releasing gas. The device has a 1- to 2-month life span, depending on how frequently the patient empties the pouch.

Reusable equipment may benefit a patient who needs a firm faceplate or who wishes to minimize cost. However, many reusable ostomy pouches aren’t odorproof.

|

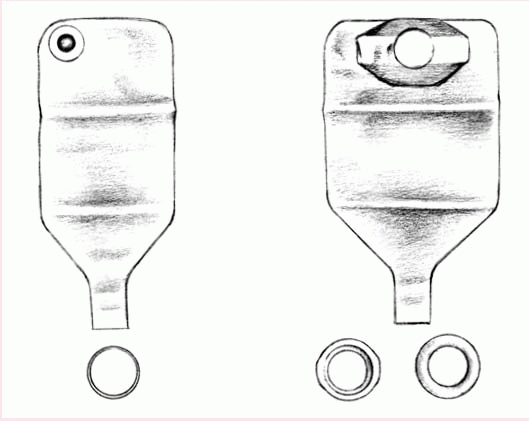

Applying a skin barrier and pouch

Fitting a skin barrier and an ostomy pouch properly can be done in a few steps. The commonly used, two-piece pouching system with flanges is shown here.

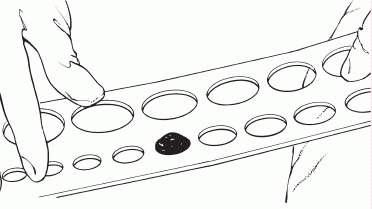

1. Measure the stoma using a measuring guide.

|

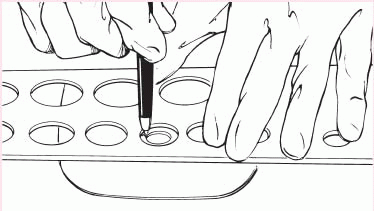

2. Trace the appropriate circle carefully on the back of the skin barrier.

|

3. Cut the circular opening in the skin barrier. Bevel the edges to prevent them from irritating the patient.

|

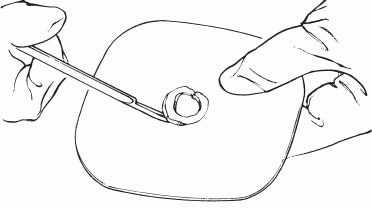

4. Remove the backing from the skin barrier and moisten it or apply barrier paste as needed along the edge of the circular opening.

|

5. Center the skin barrier over the stoma, with the adhesive side down, and gently press it to the skin.

|

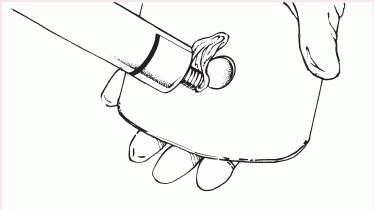

6. Gently press the pouch opening onto the ring until it snaps into place.

|

♦ Between 6 weeks and 1 year after surgery, the stoma will shrink to its permanent size, then pattern-making preparations won’t be needed unless the patient gains weight, has additional surgery, or injures the stoma.

Applying or changing the pouch

♦ Collect all equipment. Wash your hands and provide privacy. Explain the procedure to the patient.

♦ Put on gloves.

♦ As you perform each step, explain what you’re doing and why because the patient will eventually perform the procedure himself.

♦ Remove and discard the old pouch.

♦ Wipe the stoma and the peristomal skin gently with a facial tissue.

♦ Carefully wash the stoma with mild nonmoisturizing soap and water, and dry the peristomal skin by patting it gently. Let the skin dry thoroughly.

♦ Inspect the peristomal skin and stoma.

♦ If needed, shave the surrounding hair (in a direction away from the stoma) to promote a better seal and avoid skin irritation from hair pulling against the adhesive.

♦ If you’re applying a separate skin barrier, peel off the paper backing of the prepared skin barrier, center the barrier over the stoma, and press gently to ensure adhesion.

♦ You may want to outline the stoma on the back of the skin barrier (depending on the product) with a thin ring of stoma paste to provide extra skin protection. Skip this step if the patient has a sigmoid or descending colostomy, formed stools, and little mucus.

♦ Remove the paper backing from the adhesive side of the pouching system, and center the pouch opening over the stoma. Press gently to secure.

♦ For a pouching system with flanges, align the lip of the pouch flange with the bottom edge of the skin barrier flange. Gently press around the circumference of the pouch flange, beginning at the bottom, until the pouch adheres securely to the barrier flange. (The pouch will click into its secured position.) Hold the barrier against the skin, and gently pull on the pouch to confirm the seal between flanges.

♦ Encourage the patient to stay quietly in position for about 5 minutes to improve adherence. The patient’s body warmth also helps to improve adherence and to soften a rigid skin barrier.

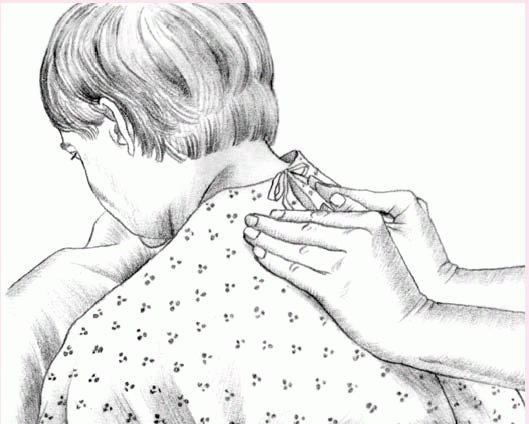

♦ Attach an ostomy belt to secure the pouch further, if desired. (Some pouches have belt loops, and others have plastic adapters for belts.)

♦ Leave a small amount of air in the pouch to allow drainage to fall to the bottom.

♦ Apply the closure clamp, if needed.

♦ If desired, apply paper tape in a picture-frame fashion to the pouch edges for additional security.

Emptying the pouch

♦ Explain the procedure to the patient and provide privacy. Wash your hands.

♦ Gather the equipment at bedside or help the patient get to the bathroom.

♦ Put on gloves.

♦ Tilt the bottom of the pouch upward, and remove the closure clamp.

♦ Turn up a cuff on the lower end of the pouch, and allow the pouch to drain into the toilet or bedpan.

♦ Wipe the bottom of the pouch with a gauze pad, and reapply the closure clamp.

♦ The bottom portion of the pouch can be rinsed with cool tap water. Don’t aim water up near the top of the

pouch because the water may loosen the seal on the skin.

pouch because the water may loosen the seal on the skin.

♦ A two-piece flanged system can also be emptied by unsnapping the pouch. Let the drainage flow into the toilet.

♦ Release flatus through the gas release valve, if the pouch has one. Otherwise, release flatus by tilting the bottom of the pouch upward, releasing the clamp, and expelling the flatus. To release flatus from a flanged system, loosen the seal between the flanges.

♦ Never make a pinhole in a pouch to release gas. The hole destroys the odor-proof seal.

Special considerations

♦ After you perform the procedure and explain it to the patient, encourage the patient’s increasing involvement in self-care.

♦ Use adhesive solvents and removers only after patch testing the patient’s skin. Some products may irritate skin or produce hypersensitivity reactions.

♦ Consider using a liquid skin sealant to give the skin added protection from drainage and adhesive irritants.

♦ Remove the pouching system if the patient reports burning or itching beneath it or purulent drainage around the stoma.

♦ Notify the physician or therapist of skin irritation, breakdown, rash, or unusual appearance of the stoma or peristomal area.

♦ Use commercial pouch deodorants, if desired. However, most pouches are odor-free, and odor should be evident only when you empty the pouch or if it leaks.

♦ Before the patient is discharged, suggest that he avoid odor-causing foods, such as fish, eggs, onions, and garlic.

♦ If the patient wears a reusable pouching system, suggest that he obtain two or more systems so that he can wear one while the other dries after it’s cleaned with soap and water or a commercially prepared cleaning solution.

♦ Failure to fit the pouch properly over the stoma or improper use of a belt can injure the stoma.

♦ Be alert for a possible allergic reaction to adhesives or other ostomy products.

Documentation

♦ Record date and time of the pouching system change. Note how the patient tolerated the procedure.

♦ Note character of drainage, including color, amount, type, and consistency.

♦ Note the appearance of the stoma and the peristomal skin.

♦ Document patient teaching content.

♦ Record patient’s response to selfcare instruction.

♦ Record your evaluation of the patient’s learning progress.

Colostomy irrigation

♦ Irrigation of a colostomy serves two purposes:

– It lets a patient with a descending or sigmoid colostomy regulate bowel function.

– It cleans the large bowel before and after tests, surgery, or other procedures.

♦ Colostomy irrigation may begin as soon as bowel function resumes after surgery. However, most clinicians suggest waiting until the patient’s bowel movements are more predictable.

♦ Initially, the nurse or the patient irrigates the colostomy at the same time

every day, recording the amount of output and any spillage that occurs between irrigations.

every day, recording the amount of output and any spillage that occurs between irrigations.

♦ About 4 to 6 weeks may pass before colostomy irrigation establishes a predictable pattern of elimination.

Equipment

Colostomy irrigation set (contains an irrigation drain or sleeve, an ostomy belt [if needed] to secure the drain or sleeve, water-soluble lubricant, drainage pouch clamp, and irrigation bag with clamp, tubing, and cone tip) ♦ 1 L of tap water irrigant warmed to about 100° F (37.8° C) ♦ warmed normal saline solution (for cleansing enemas) ♦ I.V. pole or wall hook ♦ washcloth and towel ♦ water ♦ ostomy pouching system ♦ linen-saver pad ♦ gloves ♦ optional: bedpan or chair, mild nonmoisturizing soap, rubber band or clip, and small dressing, bandage, or commercial stoma cap

Implementation

♦ Gather equipment at the bedside or help the patient get to the bathroom. Provide privacy. Wash your hands and put on gloves.

♦ Explain each step of the procedure to the patient because he’ll probably be irrigating the colostomy himself.

♦ Depending on the patient’s condition, colostomy irrigation may be performed in bed using a bedpan or in the bathroom using the toilet or a chair.

– For irrigation with the patient in bed, place the bedpan beside the bed and elevate the head of the bed to between 45 and 90 degrees, if allowed.

– For irrigation in the bathroom, have the patient sit on the toilet or on a chair facing the toilet, whichever he finds more comfortable.

♦ Set up the irrigation bag with tubing and a cone tip.

♦ Fill the irrigation bag with warmed tap water (or normal saline solution, if the irrigation is to clean the bowel).

♦ Hang the bag on the I.V. pole or a wall hook. The bottom of the bag should be at the patient’s shoulder level to prevent fluid from entering the bowel too quickly. Most irrigation sets also have a clamp that regulates the flow rate.

♦ Prime the tubing with irrigant to prevent air from entering the colon and possibly causing cramps and gas pains.

♦ If the patient is in bed, place a linen-saver pad under him to protect the sheets from getting soiled.

♦ If the patient uses an ostomy pouch, remove it.

♦ Place the irrigation sleeve over the stoma. If the sleeve doesn’t have an adhesive backing, secure the sleeve with an ostomy belt. If the patient has a two-piece pouching system with flanges, snap off the pouch and save it. Snap on the irrigation sleeve.

♦ Place the open-ended bottom of the irrigation sleeve in the bedpan or toilet to promote drainage by gravity. If needed, cut the sleeve so that it meets the water level inside the bedpan or toilet. Effluent may splash from a short sleeve or may not drain from a long one.

♦ Lubricate your gloved small finger with water-soluble lubricant, and insert the gloved finger into the stoma. If you’re teaching the patient, have him do this to determine the bowel angle at which to insert the cone safely. Expect the stoma to tighten when the finger enters the bowel and then to relax in a few seconds.

♦ Lubricate the cone with watersoluble lubricant to prevent it from irritating the mucosa.

♦ Angle the cone to match the bowel angle, and insert it into the top opening of the irrigation sleeve and then

into the stoma. Insert the cone gently but snugly; never force it into place.

into the stoma. Insert the cone gently but snugly; never force it into place.

♦ Unclamp the irrigation tubing, and let the water flow slowly.

– If you don’t have a clamp to control the flow rate of the irrigant, pinch the tubing to control the flow.

– The water should enter the colon over a period of 10 to 15 minutes.

– If the patient reports cramping, slow or stop the flow, keep the cone in place, and have the patient take a few deep breaths until the cramping stops.

– Cramping during irrigation may result from a bowel that’s ready to empty, water that’s too cold, a rapid flow rate, or air in the tubing.

♦ Have the patient remain stationary for 15 to 20 minutes to let the initial effluent drain.

♦ If the patient is ambulatory, he can stay in the bathroom until all effluent empties, or he can clamp the bottom of the drainage sleeve with a rubber band or clip and return to bed. Explain that ambulation and activity stimulate elimination.

♦ Suggest that a nonambulatory patient lean forward or massage his abdomen to stimulate elimination.

♦ Wait about 45 minutes for the bowel to finish eliminating the irrigant and effluent. Then remove the irrigation sleeve.

♦ If the irrigation was intended to clean the bowel, repeat the procedure with warmed normal saline solution until the return solution appears clear.

♦ Using a washcloth, mild nonmoisturizing soap, and water, clean the area around the stoma. Rinse and dry the area thoroughly with a clean towel.

♦ Inspect the skin and stoma for changes in appearance.

– Although it’s usually dark pink to red, the color of the stoma may change with the patient’s status.

– Notify the physician of marked changes in stoma color.

– A pale hue may result from anemia.

– Substantial darkening suggests a change in blood flow to the stoma.

♦ Apply a clean pouch. If the patient has a regular pattern of bowel elimination, he may prefer a small dressing, bandage, or commercial stoma cap.

♦ If the irrigation sleeve is disposable, discard it. If it’s reusable, rinse it and hang it to dry along with the irrigation bag, tubing, and cone.

Special considerations

♦ Irrigating a colostomy to establish a regular bowel elimination pattern isn’t successful in all patients.

– Keep a record of results.

– If the bowel continues to move between irrigations, try decreasing the volume of irrigant.

– Increasing the volume of irrigant won’t help, because it only stimulates peristalsis.

– Also consider irrigating every other day.

♦ Irrigation may help regulate bowel function in patients with a descending or sigmoid colostomy because this is the bowel’s stool storage area. However, a patient with an ascending or transverse colostomy won’t benefit from irrigation. A patient with a descending or sigmoid colostomy who’s missing part of the ascending or transverse colon may not be able to irrigate successfully, because his ostomy may function as an ascending or transverse colostomy.

♦ If diarrhea develops, stop irrigations until stools form again.

♦ Irrigation alone won’t achieve regularity for the patient. He must also observe a complementary diet and exercise regimen.

♦ If the patient has a strictured stoma that prohibits cone insertion, remove the cone from the irrigation tubing and replace it with a soft silicone catheter.

– Angle the catheter gently 2″ to 4″ (5 to 10 cm) into the bowel to instill the irrigant.

– Don’t force the catheter into the stoma, and don’t insert it farther than the recommended length because you may perforate the bowel.

♦ Observe the patient for complications.

– Bowel perforation may occur if a catheter is incorrectly inserted into the stoma.

– Fluid and electrolyte imbalances may result from using too much irrigant.

Documentation

♦ Record the date and time of irrigation. Note the patient’s tolerance of the procedure.

♦ Note type and amount of irrigant used.

♦ Note the color of the stoma.

♦ Note the character of drainage, including color, consistency, and amount.

♦ Record patient teaching content.

♦ Note patient’s response to self-care instruction.

♦ Record your evaluation of the patient’s learning progress.

Defibrillation, automated external

♦ Automated external defibrillators (AEDs) are commonly used to meet the need for early defibrillation, which is considered the most effective treatment for ventricular fibrillation.

♦ Some facilities require an AED in every noncritical care unit. Their use is also becoming common in such public places as shopping malls, sports stadiums, and airplanes.

♦ Instruction in using an AED is required as part of basic life support (BLS) and advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) training.

♦ AEDs are used increasingly to provide early defibrillation, even when no health care provider is present. The device interprets the victim’s cardiac rhythm and gives the operator step-bystep directions on how to proceed if the person needs defibrillation. Some AEDs have a “quick look” feature that allows you to see the rhythm with the paddles before the electrodes are connected.

♦ The AED is equipped with a microcomputer that senses and analyzes a patient’s heart rhythm at the push of a button. Then it audibly or visually prompts you to deliver a shock.

♦ All models have the same basic function, but they operate differently. For example, all AEDs communicate directions through messages shown on a display screen, by voice commands, or both. Some AEDs display a patient’s heart rhythm simultaneously.

♦ All devices record your interactions with the patient during defibrillation, either on a cassette tape or in a solidstate memory module.

♦ Some AEDs have an integral printer that allows immediate documentation of the event.

♦ Facility policy determines who’s responsible for reviewing all AED interactions; the patient’s physician always has that option.

♦ Local and state regulations govern who’s responsible for collecting AED case data for reporting purposes.

Equipment

AED ♦ two prepackaged electrodes ♦ electrode connector cables

Implementation

♦ After you discover that your patient is unresponsive to your questions,

pulseless, and apneic, follow BLS and ACLS protocols.

pulseless, and apneic, follow BLS and ACLS protocols.

♦ Ask a colleague to bring the AED into the patient’s room and set it up before the code team arrives.

♦ Open the foil packets that contain the two electrode pads.

♦ Attach the white electrode cable connector to one pad and the red electrode cable connector to the other. The electrode pads aren’t site-specific.

♦ Expose the patient’s chest.

♦ Remove the plastic backing film from the electrode pads, and place the electrode pad that’s attached to the white cable connector on the right upper portion of the patient’s chest, just beneath his clavicle.

♦ Place the pad that’s attached to the red cable connector to the left of the apex of the heart. To remember where to place the pads, think “white—right, red—ribs.” (Placement for the electrode pads is the same for both manual defibrillation and cardioversion.)

♦ Firmly press the ON button, and wait while the machine performs a brief self-test. Most AEDs indicate their readiness by sounding a computerized voice that says “Stand clear” or by emitting a series of loud beeps.

♦ If the AED isn’t functioning properly, it conveys the message “Don’t use the AED. Remove and continue cardiopulmonary resuscitation [CPR].”

♦ Remember to report any AED malfunctions according to facility procedure.

♦ Now the machine is ready to analyze the patient’s heart rhythm. Ask everyone to stand clear, and press the ANALYZE button when you are prompted by the machine.

– Be careful not to touch or move the patient while the AED is in analysis mode.

– If you get the message “Check electrodes,” make sure that the electrodes are correctly placed and that the patient cable is securely attached; then press the ANALYZE button again.

– In 15 to 30 seconds, the AED will analyze the patient’s rhythm.

♦ If a shock isn’t needed, the AED displays a “No shock indicated” message and prompts you to “Check patient.”

♦ If the patient needs a shock, the AED will display a “Stand clear” message and emit a beep that changes into a steady tone as it’s charging.

♦ When an AED is fully charged and ready to deliver a shock, it prompts you to press the SHOCK button. (Some fully automatic AED models automatically deliver a shock within 15 seconds after analyzing the patient’s rhythm.)

♦ Make sure that no one is touching the patient or his bed, and call out “Stand clear.” Then press the SHOCK button on the AED. Most AEDs are ready to deliver a shock within 15 seconds.

♦ After the first shock, the AED automatically reanalyzes the patient’s heart rhythm. If no additional shock is needed, the machine prompts you to check the patient. However, if he’s still in ventricular fibrillation, perform CPR for 2 minutes and then press the analyze button on the AED to identify the heart rhythm.

♦ If the patient is still in ventricular fibrillation, the AED will prompt you to press the shock button. A second shock at 360 joules will be delivered.

♦ If the patient is still in ventricular fibrillation, continue the algorithm sequence until the code team leader arrives.

♦ After the code, remove and transcribe the computer memory module or tape, or prompt the AED to print a rhythm strip with the code data. Follow facility policy for analyzing and storing the code data.

Special considerations

♦ AEDs vary from one manufacturer to another, so familiarize yourself with the equipment at your facility.

♦ The operation of the AED should be checked every shift and after each use.

♦ Because defibrillation can accidentally shock those providing care, emergency responders should be alerted when a shock is being discharged.

Documentation

♦ Record all information required by the appropriate code form.

♦ Record the patient’s name, age, medical history, and chief complaint, if available.

♦ Note the time you found the patient in arrest.

♦ Note the time CPR began.

♦ Note the time when the AED was applied.

♦ Record the number of shocks the patient received.

♦ Note the time that the patient’s pulse was regained.

♦ Record all postarrest care given.

♦ Note findings of physical examination.

Doppler use

♦ The Doppler ultrasound blood flow detector is more sensitive than palpation for determining a patient’s pulse rate; it’s especially useful for a pulse that’s faint or weak on palpation.

♦ Unlike palpation, which detects expansion and retraction of the arterial walls, this instrument detects the motion of red blood cells (RBCs).

Equipment

Doppler ultrasound blood flow detector ♦ coupling or transmission gel ♦ soft cloth ♦ antiseptic solution or soapy water

Implementation

♦ Apply a small amount of coupling or transmission gel (not water-soluble lubricant) to the ultrasound probe.

♦ Position the probe on the skin directly over the selected artery.

♦ If the device you’re using has a speaker, turn the instrument on. Moving counterclockwise, set the volume control to the lowest setting.

♦ If your model doesn’t have a speaker, plug in the earphones and slowly raise the volume. This device is basically a stethoscope fitted with an audio unit, a volume control, and a transducer, which amplifies the movement of RBCs.

♦ To obtain the best signals with either device, tilt the probe 45 degrees from the artery and apply gel between the skin and the probe. Slowly move the probe in a circular motion to locate the center of the artery and the Doppler signal—a hissing noise at the heartbeat. If needed for future use, mark the location with a permanent marker.

♦ Avoid moving the probe rapidly because it distorts the signal.

♦ Count the signals for 60 seconds to determine the pulse rate.

♦ After you’ve measured the pulse rate, clean the probe with an antiseptic solution.

♦ Don’t immerse the probe in water or bump it against a hard surface.

Documentation

♦ Note the location and quality of the pulse.

♦ Record the patient’s pulse rate.

♦ Note the time of measurement.

Electrocardiography

♦ One of the most valuable and frequently used diagnostic tools, electrocardiography measures the heart’s electrical activity as waveforms.

♦ Impulses moving through the heart’s conduction system create electric currents that can be monitored on the body’s surface. Electrodes attached to the skin detect these electric currents and transmit them to an electrocardiogram (ECG) machine, which records cardiac activity.

♦ An ECG can be used to identify myocardial ischemia and infarction, rhythm and conduction disturbances, chamber enlargement, electrolyte imbalances, and drug toxicity.

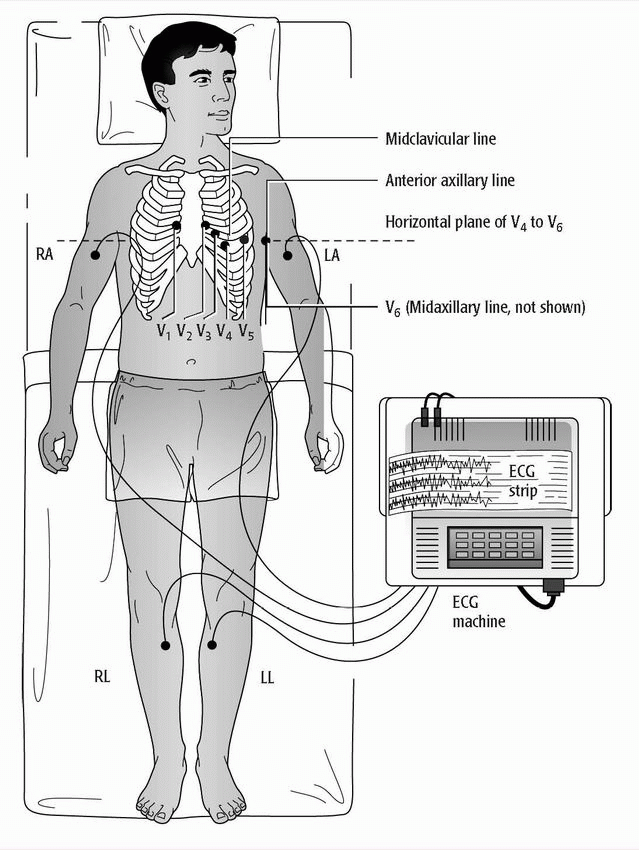

♦ The standard 12-lead ECG uses a series of electrodes placed on the limbs and the chest wall to assess the heart from 12 different views (leads). (See 12-lead electrocardiogram electrode placement.)

– The 12 leads consist of three standard bipolar limb leads (designated I, II, III), three unipolar augmented leads (aVR, aVL, aVF), and six unipolar precordial leads (V1 to V6).

– The limb leads and augmented leads show the heart from the frontal plane.

– The precordial leads show the heart from the horizontal plane.

♦ The ECG device measures and averages the differences between the electrical potential of the electrode sites for each lead and graphs them over time. This creates the standard ECG complex, called PQRST.

– The P wave represents atrial depolarization.

– The QRS complex represents ventricular depolarization.

– The T wave represents ventricular repolarization.

♦ Variations of standard ECG include exercise ECG (stress ECG) and ambulatory ECG (Holter monitoring).

– Exercise ECG monitors heart rate, blood pressure, and ECG waveforms as the patient walks on a treadmill, pedals a stationary bicycle, or pedals an arm exercise machine.

– Patients unable to exercise may be given adenosine (Adenocard) or dipyridamole (Persantine) to mimic the effects of exercise on the heart.

– For thallium or myoview exercise ECGs, radionucleotide drugs are given to enable heart scans to be done in addition to the ECG.

– For ambulatory ECG, the patient wears a portable Holter monitor to record heart activity continually over 24 hours.

♦ Today, ECG is typically accomplished using a multichannel method. All ten electrodes are attached to the patient at once, and the machine prints a simultaneous view of all leads.

Equipment

ECG machine ♦ recording paper ♦ disposable pregelled electrodes ♦ 4″ × 4″ gauze pads ♦ optional: clippers, marking pen

Implementation

♦ Verify the patient’s identity using two patient identifiers.

♦ Place the ECG machine close to the patient’s bed, and plug the power cord into the wall outlet.

♦ Keep the patient away from objects that might cause electrical interference, such as equipment, fixtures, and power cords.

♦ As you set up the machine to record a 12-lead ECG, explain the procedure to the patient and provide privacy.

– Tell him that the test records the heart’s electrical activity and it may be repeated at certain intervals.

– Emphasize that no electrical current will enter his body and that the test is painless.

– Also, tell him that the test typically takes about 5 minutes.

♦ Wash your hands.

♦ Have the patient lie in a supine position in the center of the bed with his arms at his sides. You may raise the head of the bed to promote his comfort.

♦ Expose his arms and legs, and drape him appropriately.

– His arms and legs should be relaxed to minimize muscle trembling, which can cause electrical interference.

– If the bed is too narrow, place the patient’s hands under his buttocks to prevent muscle tension.

– Also use this technique if the patient is shivering or trembling.

– Make sure his feet aren’t touching the bed board.

♦ Select flat, fleshy areas to place the electrodes. Avoid muscular and bony areas. If the patient has an amputated limb, choose a site on the residual limb.

♦ Clean excess oil or other substances from the skin to enhance electrode contact.

♦ Apply the disposable electrodes. Peel off the contact paper and apply them directly to the prepared site, as recommended by the manufacturer’s instructions.

♦ To guarantee the best connection to the leadwire, position disposable electrodes on the legs with the lead connection pointing superiorly.

♦ Connect the limb leadwires to the electrodes.

♦ You’ll see that the tip of each leadwire is lettered and color-coded for easy identification.

– The white or RA leadwire goes to the right arm.

– The green or RL leadwire goes to the right leg.

– The red or LL leadwire goes to the left leg.

– The black or LA leadwire goes to the left arm.

– The V1 to V6 leadwires go to the chest.

♦ Expose the patient’s chest. Apply a disposable electrode at each electrode position.

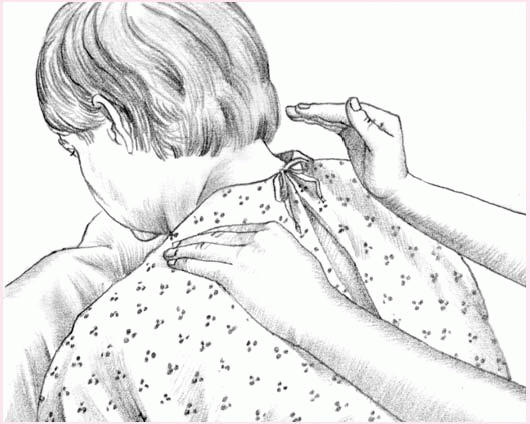

♦ If your patient is female, place the chest electrodes below the breast tissue. In a large-breasted woman, you may need to displace the breast tissue laterally.

♦ Check to see that the paper speed selector is set to the standard 25 mm/second and that the machine is set to full voltage. The machine will record a normal standardization mark—a square that’s the height of two large squares or 10 small squares on the recording paper.

♦ If needed, enter the appropriate patient identification data.

♦ If any part of the waveform extends beyond the paper when you record the ECG, adjust the normal standardization to half-standardization. Note this adjustment on the ECG strip because this will need to be considered in interpreting the results.

♦ Now you’re ready to start recording.

– Ask the patient to relax and breathe normally.

– Tell him to lie still and not to talk when you record his ECG.

♦ Then press the AUTO button.

– Observe the tracing quality.

– The machine will record all 12 leads automatically, recording three consecutive leads simultaneously.

– Some machines have a display screen so you can preview waveforms before the machine records them on paper.

♦ When the machine finishes recording the 12-lead ECG, remove the electrodes and clean the patient’s skin.

Special considerations

♦ Small areas of hair on the patient’s chest or extremities may be clipped, but this usually isn’t needed.

♦ If the patient’s skin is exceptionally oily, scaly, or diaphoretic, rub the electrode site with a dry 4″ × 4″ gauze or alcohol pad before applying the electrode to help reduce interference in the tracing.

♦ If the patient’s respirations distort the recording, ask him to hold his breath briefly to reduce baseline wander in the tracing.

♦ If the patient has a pacemaker, you can perform an ECG with or without a magnet, according to the physician’s orders. Be sure to note the presence of a pacemaker and the use of the magnet on the ECG printout.

Documentation

♦ Record the patient’s name, identification number, facility name, date, and time on the ECG recording.

♦ Note any appropriate clinical information on the ECG.

♦ Record the date and time of test in your notes.

♦ Note significant responses by the patient in your notes.

Feeding tube maintenance and removal

♦ Inserting a feeding tube nasally or orally into the stomach or duodenum provides nourishment to a patient who can’t or won’t eat.

♦ The tube also allows supplemental feedings for a patient with very high nutritional requirements, such as an unconscious patient or one with extensive burns.

♦ The preferred route is nasal, but the oral route may be used for patients with such conditions as a deviated septum or an injury of the head or nose.

♦ The physician may order duodenal feeding if the patient can’t tolerate gastric feeding or if gastric feeding may cause aspiration.

♦ The absence of bowel sounds or possible intestinal obstruction contraindicates the use of a feeding tube.

♦ Feeding tubes differ somewhat from standard nasogastric tubes.

– Made of silicone, rubber, or polyurethane, feeding tubes have small diameters and great flexibility.

– These qualities reduce oropharyngeal irritation, necrosis resulting from pressure on the tracheoesophageal wall, irritation of the distal esophagus, and discomfort from swallowing.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree