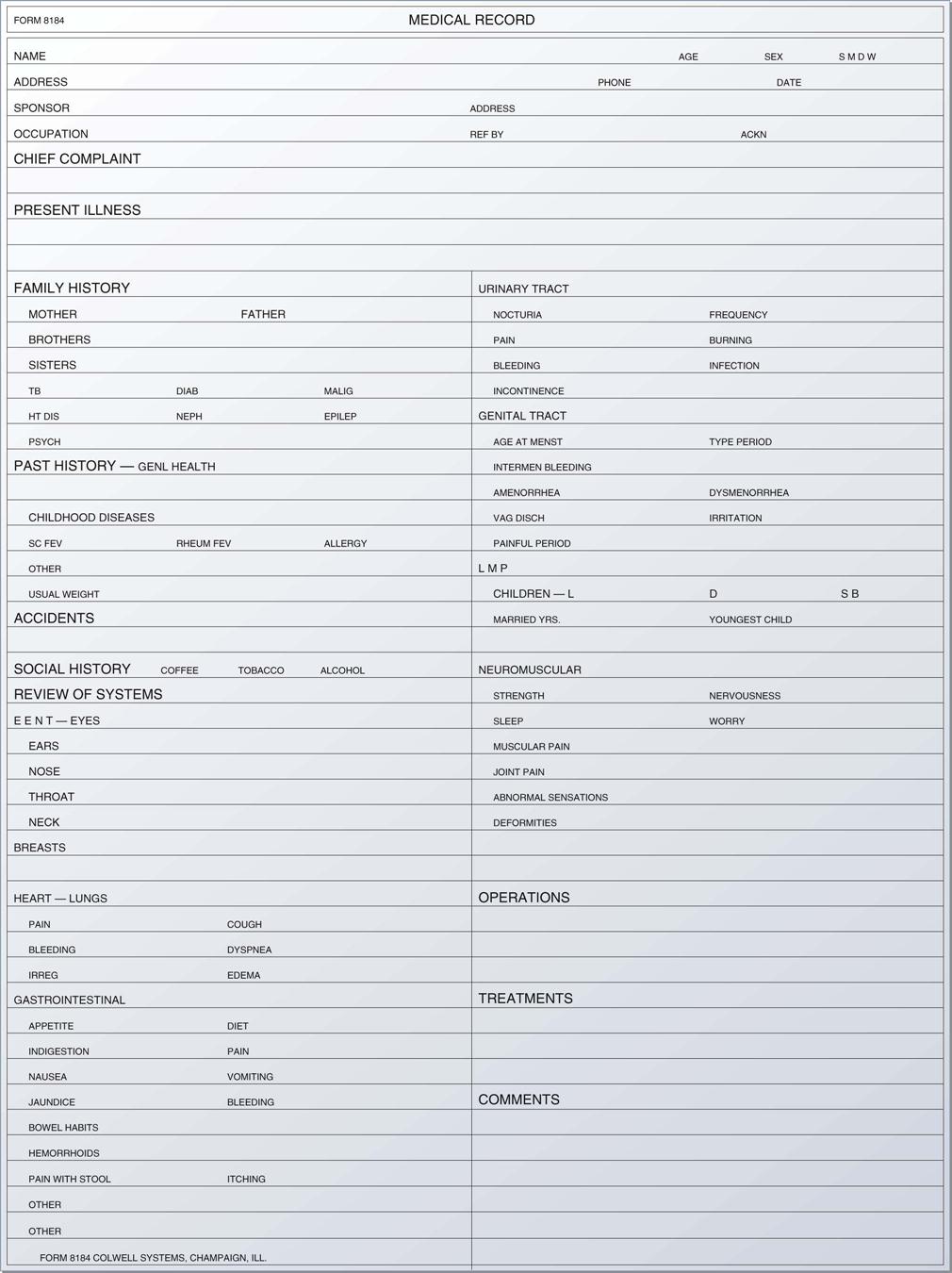

1. Define, spell, and pronounce the terms listed in the vocabulary. 2. Apply critical thinking skills in performing patient assessment and care. 3. Employ the concept of holistic care in the patient assessment process. 4. Describe the components of the patient’s medical history. 5. Define and apply the qualities of a helping relationship. 6. Display sensitivity to diverse patient populations. 8. Recognize the importance of nonverbal communication when interacting with patients. 9. Identify barriers to communication and their impact on patient assessment. 11. Use therapeutic communication techniques with patients across the lifespan. 12. Demonstrate professional patient interviewing techniques. 14. Differentiate among various medical records systems employed in the physician’s office. 16. Determine risk management strategies for the ambulatory care setting. 17. Use reflection, restatement, and clarification techniques to obtain a patient history. biophysical (bi-o-fi′-zi-kuhl) The science of applying physical laws and theories to biologic problems. cognitive (kog′-nuh-tiv) Pertaining to the operation of the mind; referring to the process by which we become aware of perceiving, thinking, and remembering. congruence (kon-groo′-ents) Agreement; the state that occurs when the verbal expression of the message matches the sender’s nonverbal body language. familial Occurring in or affecting members of a family more than would be expected by chance. present illness The chief complaint, written in chronologic sequence, with dates of onset. psychosocial Pertaining to a combination of psychological and social factors. rapport (ra-por′) A relationship of harmony and accord between the patient and the healthcare professional. signs Objective findings determined by a clinician, such as a fever, hypertension, or rash. symptoms Subjective complaints reported by the patient, such as pain or visual disturbances. Chris Isaccson, CMA (AAMA), works in an ambulatory care setting at the community hospital. He is responsible for initial patient interviews, taking medical histories, and documentation. Chris is having difficulty gathering the information needed from some of the patients. They do not always respond openly and honestly to him, and the attending physician is not satisfied with his work. His supervisor is responsible for helping him improve his interviewing skills. While studying this chapter, think about the following questions: As medical professionals directly involved in gathering information from patients about their health status, medical assistants must remember that a healthy state is more than the absence of disease. The assessment process should be a reflection of the entire patient, not just a report about signs and symptoms. Individual lifestyles and environmental factors can create disease and therefore should be considered when we gather information about the patient’s chief complaint. For example, if a patient smokes or works in a stressful occupation, he or she may be more prone to hypertension. As health professionals, we should consider all patient factors, including cognitive, psychosocial, and behavioral data, when gathering information about the patient’s health status. Consider this: do you think a patient who does not have health insurance to help pay for medication can afford prescribed drugs? This method of analyzing the development of disease is based on a holistic perspective. Holistic patient care recognizes that illness is the result of many factors, not just physical ones. Assessment factors are a list of biophysical signs and symptoms. As the first step in treating a disease process, the physician must determine the patient’s medical diagnosis. The identification of disease begins with the physician’s working diagnosis, which he or she has determined through the patient’s history, the report of the chief complaint, and the physical examination. Next, the physician orders laboratory tests, diagnostic examinations, and/or a referral visit to another physician to substantiate or refute the working diagnosis. Once the test results have been received, the clinical diagnosis is established. The patient then is treated, and after a period of time is re-evaluated to see whether the clinical diagnosis has changed. If it has, the new diagnosis is called the differentiated diagnosis. The physician continues to evaluate the patient’s progress, ordering tests and/or altering treatment as needed. However, patient care does not start with the physical examination; it begins when the patient first makes contact with the office. Even before the examination, the medical assistant has the opportunity to interact with the patient to ensure that he or she feels comfortable during the process and that all the necessary information is obtained. Interviewing patients, assisting with examinations, and documentation are important responsibilities for a medical assistant. You must know the components of a medical history and the techniques for securing, because these will help the physician diagnose and treat the patient. The more complete the medical history, the more efficient the physician’s care and treatment will be. When a new patient calls or comes in for an appointment, the person is asked to complete a health history form. Besides being useful for diagnosing and treating the patient, the self-history allows the patient more participation in the process. The form may be mailed to the patient’s home before the appointment or may be completed in the office during the first visit. If you are responsible for taking a portion of the medical history, conduct the interview in a private area free of outside interference and beyond the hearing range of other patients. Patients will not talk freely where they may be overheard or interrupted. Legally and ethically, the patient has the right to privacy, and access to the patient’s medical record is permitted only to healthcare workers directly involved in the patient’s care or to individuals the patient has specified on his or her Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) release form. Listen to the patient. Do not express surprise or displeasure at any of the patient’s statements. Remember, you are there not to pass judgment but to gather medical data. Documentation of information gathered while taking the medical history is included in the progress notes section of the medical chart. The medical assistant records the information in an organized manner, exactly as given by the patient, without opinion or interpretation. The progress notes should include the purpose of the patient’s visit, written as the chief complaint (CC), and the patient’s vital signs (VS), including height and weight, if preferred by the physician; in addition, if the patient reports pain, it should be documented using a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 being the least amount of pain and 10 being the greatest amount. In some facilities, the physician takes the medical history during the patient’s initial visit. The physician correlates the physical findings in the examination with the information in the history. The complete medical history and the physical examination are the starting point and foundation of all patient-physician contacts. Medical history forms vary, depending on the physician’s preference and the practice specialty (Figure 28-1). The most commonly used medical history forms include these components: To provide high-quality patient care, we must communicate effectively with the patient and provide a warm, caring environment. Positive reactions and interactions with the patient are vital. Because medical care by nature is extremely personal, a medical assistant must always remember that each patient is an individual with certain anxieties. These anxieties often cause people to act and react in different ways; therefore, effective verbal and nonverbal communication with each patient is absolutely essential. Healthcare professionals accept the responsibility of developing helping relationships with their patients. The interpersonal nature of the patient–medical assistant relationship carries with it a certain amount of responsibility to forget one’s self-interest and focus on the patient’s needs. A medical assistant can elicit either a positive or a negative response to patient care simply by the way he or she treats and interacts with patients. You usually are the first person with whom the patient communicates; therefore, you play a vital role in initiating therapeutic patient interactions (Procedure 28-1). Practicing respectful patient care is extremely important when working with a diverse patient population. Empathy is the key to creating a caring, therapeutic environment. Empathy goes beyond sympathy. A medical assistant who is empathetic respects the individuality of the patient and attempts to see the person’s health problem through his or her eyes, recognizing the effect of all holistic factors on the patient’s well-being. Empathetic sensitivity to diversity first requires those interested in healthcare to examine their own values, beliefs, and actions; you cannot treat all patients with care and respect until you first recognize and evaluate personal biases. We think and act a certain way for many reasons. The first step in understanding the process is to evaluate your individual value system. Why do you have certain attitudes or beliefs about the worth of individuals or things? Many different factors influence the development of a value system. Value systems begin as learned beliefs and behaviors. Families and cultural influences shape the way we respond to a diverse society. Other factors that influence reactions include socioeconomic and educational backgrounds. To develop therapeutic relationships, you must recognize your own value system to determine whether it could affect your method of interaction. Preconceived ideas about people because of their race, religion, income level, ethnic origin, sexual orientation, or gender can act as barriers to the development of a therapeutic relationship. You will be unable to treat your patients empathetically unless you can connect with them in some way. Personal biases or prejudices are monumental barriers to the development of therapeutic relationships (Figure 28-2). The linear communication model describes communication as an interactive process involving the sender of the message, the receiver, and the crucial component of feedback to confirm reception of the message. The message can be sent by a number of different methods, such as face-to-face communication, telephone, e-mail, and letter; however, there is no way to confirm that the message was actually received unless the patient provides feedback about what he or she interpreted from the message. Feedback completes the communication cycle by providing a means for us to know exactly what message the patient received and therefore whether it requires clarification. For example, as a medical assistant, one of your responsibilities will be to provide patient education on how to prepare for diagnostic studies. Let’s say you have to explain to an elderly patient how to prepare for a colonoscopy. Even though you provide a detailed explanation of the preparation procedure, in addition to a handout explaining the step-by-step process, how do you really know whether the patient understands? You ask the patient to provide feedback by explaining the process back to you. As a member of the healthcare team, you must become an effective communicator. You will play a vital role in collecting and documenting patient information. If your methods of collection or recording are faulty, the quality of patient care may be seriously impaired. Active listeners go beyond hearing the patient’s message to concentrating, understanding, and listening to the main points in the discussion. Active listening techniques encourage patients to expand on and clarify the content and meaning of their messages. They are very useful communication tools to implement when a patient is agitated or upset, because these methods help the medical assistant clarify the important details of the patient’s chief complaint. Three processes are involved in active listening: restatement, reflection, and clarification. Restatement is simply paraphrasing or repeating the patient’s statements with phrases such as, “You are saying …” or “You are telling me the problem is …” Reflection involves repeating the main idea of the conversation while also identifying the sender’s feelings. For example, if the mother of a young patient is expressing frustration about her child’s behavior, a reflective statement identifies that feeling with the response, “You sound frustrated about …” Or, if a patient who has been newly diagnosed with insulin-dependent diabetes shows anxiety about administering injections, an appropriate reflective statement recognizes the patient’s feelings: “You appear anxious about …” Reflective statements clearly demonstrate to patients that you are not only listening to their words; you also are concerned and are attending to their feelings. Clarification seeks to summarize or simplify the sender’s thoughts and feelings and to resolve any confusion in the message. Questions or statements that begin with “Give me an example of …” or “Explain to me about …” or “So what you’re saying is …” help patients focus on the chief complaint and give you the opportunity to clear up any misconceptions before documenting patient information. Listening is not a passive role in the communication process; it is active and demanding. You cannot be preoccupied with your own needs, or you will miss something important. For the duration of the patient interview, no one is more important than this particular patient. Listen to the way things are said, the tone of the patient’s voice, and even to what the patient may not be saying out loud but is saying very clearly with body language. Much of what we communicate to our patients is conveyed through the use of conscious or unconscious body language. Our nonverbal actions, such as gestures, facial expressions, and mannerisms, are learned behaviors that are greatly influenced by our family and cultural backgrounds. The body naturally expresses our true feelings; in fact, experts say that more than 90% of communication is nonverbal. Most of the negative messages communicated through body language are unintentional; therefore, it is important to remember while conducting patient interviews that nonverbal communication can seriously affect the therapeutic process. The verbal messages you send are only part of the communication process. You have a specific context in mind when you send your words, but the receiver puts his or her own interpretations on them. The receiver attaches meaning determined by his or her past experiences, culture, self-concept, and current physical and emotional states. Sometimes these messages and interpretations do not coincide. Feedback from the patient is crucial in determining whether the patient understood the message. Successful communication requires mutual understanding by both the interviewer and the person being interviewed. Observing your patient during the interview fosters mutual understanding. The purpose of observing nonverbal communication is to become sensitive to or aware of the feelings of others as conveyed by small bits of behavior rather than words. This sensitivity enables you to adapt your behavior to these feelings; to deliberately select your response, either verbal or nonverbal; and thereby to have a favorable effect on others. The favorable effect may consist of providing emotional support, conveying that you care, defusing the patient’s fear or anger, or providing an invitation to release pent-up feelings by talking about the situation that aroused the feelings. Table 28-1 lists some nonverbal behaviors by patients that may indicate anxiety, frustration, or fear. TABLE 28-1 Observation of Nonverbal Communication in Patients You can do much to put a patient at ease by the tone of your voice. Your facial expression and the ease and confidence of your movements demonstrate a sincere interest to the patient. Therapeutic use of space and touch also are important ways of sending nonverbal messages to your patients. You should establish eye contact, sit in a relaxed but attentive position, and avoid using furniture as a barrier between you and the patient. Give the patient your undivided attention and let your body language inform each patient that you are interested in his or her medical problems (Figure 28-3). The key to successful patient interaction is congruence between verbal and nonverbal messages. Although choosing the correct words is very important, only 7% of the message received is verbal; therefore, to be seen as honest and sensitive to the needs of your patients, you must be aware of your nonverbal behavior patterns. The nonverbal message the patient receives from the medical assistant’s listening behavior should be, “You are a person of worth, and I am interested in you as a unique individual.” Before you meet with the patient, prepare the physical setting, which may be an examination room or an office. In any location, optimum conditions are important to achieving a smooth, productive interview. An open-ended question or statement asks for general information or states the topic to be discussed but only in general terms. Use this communication tool to begin the interview, to introduce a new section of questions, or whenever the person introduces a new topic. It is a very effective method of gathering more details from the patient about the chief complaint or health history. Examples include: “What brings you to the doctor?” “How have you been getting along?” “You mentioned having dizzy spells. Tell me more about that.” This type of question or statement encourages patients to respond in a manner they find comfortable. It allows patients to express themselves fully and provide comprehensive information about their chief complaint. Direct, or closed, questions ask for specific information. This form of questioning limits the answer to one or two words, a “yes” or “no” in many cases. Use this form of question when you need confirmation of specific facts, such as when asking about past health problems. For example: The interview, or gathering the patient’s medical history, is the first and most important part of data collection. The medical history identifies the patient’s health strengths and problems and is a bridge to the next step in data collection, the physical examination performed by the physician. At this point, the patient knows everything about his or her own health status and you know nothing. Your skill in interviewing helps glean the necessary information and builds rapport for a successful working relationship. Consider the interview as a form of contract between you and your patient. The contract consists of spoken and unspoken language and addresses what the patient needs and expects from the healthcare visit. The patient interview consists of three stages: the initiation or introduction, the body, and the closing. The initiation of the interview is the time to introduce yourself, to identify the patient, and to determine the purpose of the interview (Figure 28-4). If you are nervous about how to begin, remember to keep it short. The patient probably is nervous, too, and is anxious to get started. Address the patient by his or her last name and give the reason for the interview. For example: “Mr. Coleman, my name is Stacey, and I am a certified medical assistant who works with Dr. Yang. I have some questions to ask you about your health history. Would you mind sharing this information with me?”

Patient Assessment

Learning Objectives

Vocabulary

Scenario

Medical History

Collecting the History Information

Components of the Medical History

Understanding and Communicating with Patients

Sensitivity to Diversity

Therapeutic Techniques

Active Listening Techniques

Nonverbal Communication

AREA OBSERVED

OBSERVATION

INDICATION

Breathing patterns

Rapid respirations, sighing, shallow thoracic breathing

Anxiety, boredom, pain

Eye patterns

No eye contact, side-to-side movement, looking down at the hands

Anxiety, distrust, embarrassment

Hands

Tapping fingers, cracking knuckles, continuous movement, sweaty palms

Anxiety, worry, fear

Arm placement

Folded across chest, wrapped around abdomen

Anxiety, worry, fear, pain

Leg placement

Tension, crossed and/or tucked under, tapping foot, continuous movement

Frustration, anger

Environmental Factors

Open-Ended Questions or Statements

Closed Questions

Interviewing the Patient

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Patient Assessment

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access