Chapter 5 Pain

The Fifth Vital Sign

Safe and Effective Care Environment

1. Identify the role of the nurse as an advocate for patients in acute pain and chronic pain.

2. Explain the importance of collaborating with the health care team in developing the pain management plan of care.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

3. Develop a teaching plan for patients to include complementary and alternative therapies for pain management.

4. Incorporate special considerations for older adults related to pain assessment and management.

5. Describe how to provide patient-centered care by respecting patients’ preferences, values, and beliefs regarding pain and its management.

6. Discuss the attitudes and knowledge of patients and their families regarding pain assessment and management.

7. Perform a complete pain assessment, and document per agency policy.

8. Differentiate between addiction, pseudoaddiction, tolerance, and physical dependence.

9. Compare and contrast the characteristics of the major types of pain and examples of each.

10. Explain the role of non-opioid analgesics in pain management.

11. Develop a plan of care to prevent common side effects of opioid analgesics.

12. Compare the advantages and disadvantages of drug administration routes.

13. Determine the patient’s need for pain medication, including PRN and adjuvant therapy.

14. Prioritize care for the patient receiving patient-controlled analgesia.

15. Outline care for a patient receiving epidural analgesia.

16. Identify the importance of incorporating nonpharmacologic interventions into the patient’s plan of care as needed to control pain.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision\xE2\x80’Making Challenges

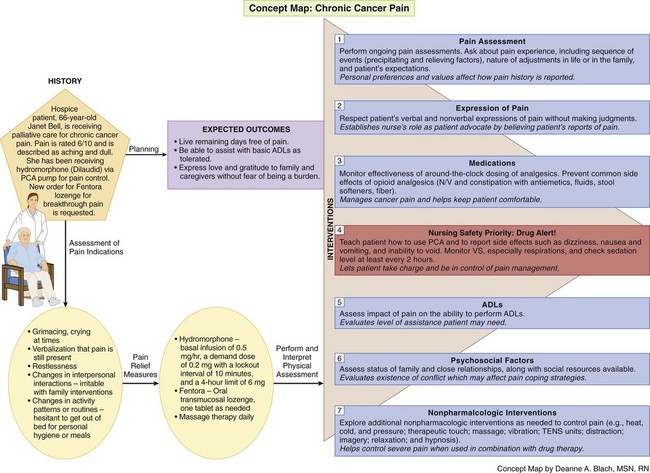

Concept Map: Chronic Cancer Pain

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Overview

Definitions of Pain

Pain is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage. In their classic work, McCaffery and Pasero (1999) offered a more personal explanation of pain when they stated that pain is whatever the experiencing person says it is and exists whenever he or she says it does. This understanding of pain requires that the patient be seen as the authority on the pain and as the only one who can define the experience. In other words, self-report is always the most reliable indication of pain. Nurses who approach pain from this perspective can help the patient achieve effective pain management by advocating for proper control. Of course, if the patient cannot communicate, self-report is not possible. In this case, a variety of methods and observation of nonverbal indicators are used to assess the pain, as described later in this chapter.

Scope of the Problem

Inadequate pain management can lead to many consequences affecting the patient and family members. These consequences often affect the patient’s and family’s quality of life (Table 5-1). Therefore, as a nurse, you have a legal and ethical responsibility to ensure that patients receive adequate pain control. In 2000, The Joint Commission (TJC) published pain standards approved by the American Pain Society. TJC states that patients in all health care settings, including home care, have a right to effective pain management.

TABLE 5-1 IMPACT OF UNRELIEVED PAIN

| Physiologic Impact |

| Quality-of-Life Impact |

| Financial Impact |

Categorizing Pain

Pain can be categorized in two ways: by type related to the characteristics of the pain (Table 5-2) or by the physiologic source of the pain. The two major types of pain are acute and chronic. Acute pain often results from sudden, accidental trauma (e.g., fractures, burns, lacerations) or from surgery, ischemia, or acute inflammation. Chronic pain or persistent pain is further divided into two subtypes. Chronic cancer pain is pain associated with cancer or another progressive disease such as acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). The cause of pain is usually life threatening. Chronic non-cancer pain is associated with tissue injury that has healed or is not associated with cancer, such as arthritis or chronic back pain. This type of pain is the most common.

TABLE 5-2 CHARACTERISTICS OF ACUTE PAIN AND CHRONIC PAIN

| ACUTE | CHRONIC* (OR PERSISTENT) |

|---|---|

* Includes chronic cancer pain and chronic non-cancer pain.

Chronic Pain

Chronic Non-Cancer Pain

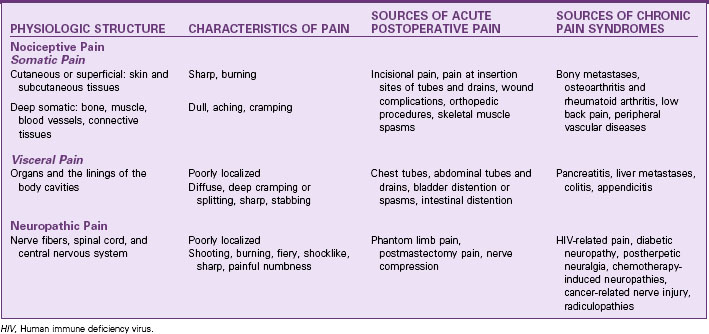

Pain is also categorized as either nociceptive (normal processing of pain) or neuropathic (abnormal pain processing). Nociceptive pain is either visceral or somatic (Table 5-3). Somatic pain arises from the skin and musculoskeletal structures, and visceral pain arises from organs. Neuropathic pain is one of the most challenging types of chronic non-cancer pains; it results from some type of nerve injury. Neuropathic pain is still not completely understood. It is divided into centrally or peripherally generated pain. Regardless of the cause, neuropathic pain is described as burning (most common), shooting, stabbing, and feeling “pins and needles.”

Theoretical Bases for Pain

Pain Transmission

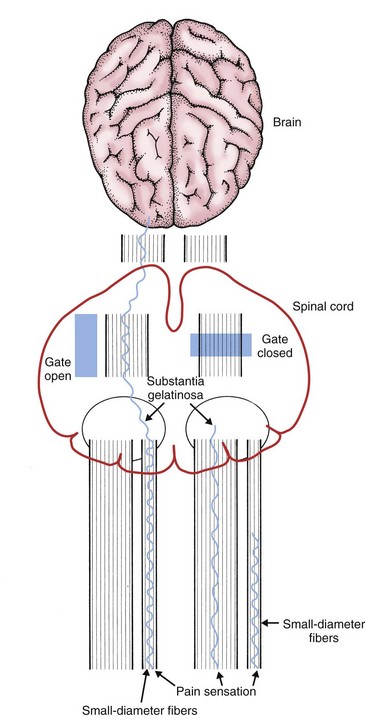

Although many theories of pain have been discussed, the classic gate control theory by Melzack and Wall (1982) still forms the basis of what is believed by most pain researchers today. According to this theory, a gating mechanism occurs in the spinal cord. Nerve fibers (A delta and C fibers) transmit pain impulses from the periphery of the body. These impulses travel to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, specifically to the substantia gelatinosa, where the gating mechanism occurs. When the gate is opened, pain impulses ascend to the brain; when the gate is closed, the impulses do not get through and pain is not perceived (Fig. 5-1).

Pain Perception

Considerations for Older Adults

Age can influence how pain is perceived, assessed, and treated. It has been well documented that the incidence of pain in older adults is high, as is risk for undertreatment. Chart 5-1 addresses special considerations for assessing and managing pain in older adults.

Chart 5-1 Nursing Focus on the Older Adult

Pain

Beliefs About Pain

• In addition to receiving less analgesia, older adults tend to report pain less often than do younger adults. These findings may be related to beliefs and concerns about pain and the reporting of pain. Many older people hold these beliefs and concerns about pain:

• Nurses should be aware of the beliefs of older patients regarding pain management. Nurses and other caregivers often undermedicate these patients and are sometimes reluctant to administer the prescribed analgesics.

Assessment

• Ask about present pain only; ask the patient to assess his or her pain whenever possible.

• Ask the patient’s family or other caregiver whenever the patient cannot respond appropriately.

• Document using a standard behavioral pain assessment scale.

• Explain the scale each time it is used.

• Use verbal descriptions such as “ache,” “sore,” and “hurt,” rather than the word “pain.”

• Use visual representations of pain measures rather than mental images of pain rating scales. Be sure that the patient is wearing glasses and hearing aids if needed and available.

• Alter a written pain scale to include large lettering, adequate space between lines, non-glossy paper, and color for increased visualization.

• Provide adequate lighting and privacy to avoid distracting background noise.

Management of Pain

• Use around-the-clock dosing of analgesics.

• Consider an analgesic trial in a cognitively impaired patient.

• Beware of adverse effects of acetaminophen (hepatotoxicity, nephrotoxicity) and NSAIDs (GI bleeding, nephrotoxicity).

• Start low and go slow with drug dosing, especially opioids.

• Avoid the use of meperidine, codeine, and propoxyphene (available in combination with acetaminophen, as Darvocet).

• Do not give meperidine to older adults and those with renal disease because of the prolonged half-life of its drug metabolite normeperidine.

• Use non-drug pain relief measures or adjuvant drugs as appropriate.

• To promote drug adherence, suggest using a pillbox to organize each day’s medications.

• Teach the patient and family or other caregiver about the drug regimen and when to notify the primary care provider if adverse drug effects occur.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

History

• Pain experience, including the sequence of events (precipitating and relieving factors)

• Nature of adjustments, if any, in life or in the family

• Beliefs about the cause of the pain and what should be done about it (patient’s expectations)

• Precipitating factors. Does the person associate any activities, food, or other environmental factors with the onset of pain? What does the patient think causes the present pain? Was the onset of pain sudden or slow? Has the patient done anything or taken anything to relieve the pain? What were the results of the intervention?

• Aggravating factors. What factors make the pain worse? What influence has this pain had on the patient’s activity? What lifestyle changes have been affected (e.g., diet, job, sleep)?

• Localization of pain. Can the person localize the pain or describe where it travels or radiates?

• Character and quality of pain. What words does the patient use to describe the pain and its character, quality, or intensity?

• Duration of pain. How long has the patient experienced this pain?

Physical Assessment/Clinical Manifestations

The mnemonic PQRST may be helpful in organizing the pain assessment (Jarvis, 2012):

P: Precipitating or palliative. What brings it on? What makes it better? Worse? When did you first notice it?

Q: Quality or quantity. How does it look, feel, or sound? How intense/severe is it?

R: Region or radiation. Where is it? Does it spread anywhere?

S: Severity scale. How bad is it (on a scale of 1 to 10)? Is it getting better, worse, or staying the same?

T: Timing. Onset—Exactly when did it first occur? Duration—How long did it last? Frequency—How often does it occur?

Location of Pain

Pain may be described as belonging to one of four categories related to its location:

• Localized pain is pain confined to the site of origin.

• Projected pain is pain along a specific nerve or nerves.

• Radiating pain is diffuse pain around the site of origin that is not well localized.

• Referred pain is pain perceived in an area distant from the site of painful stimuli.

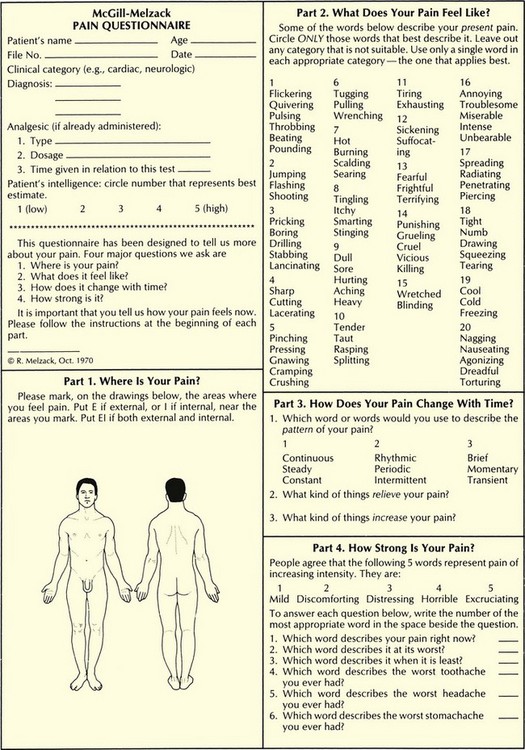

Ask the patient who has difficulty specifying the exact location of pain to point to the painful areas on his or her own body or on another person. If the patient is able to communicate, have him or her point to or shade in the painful areas on a diagram of the front and back of the human body (Fig. 5-2). Encourage those who cannot identify the painful areas and state that they just “hurt all over” to focus on parts of the body that are not painful. Ask the patient to concentrate on different body parts, beginning with the hand and fingers of one extremity, and identify the presence or absence of pain. By focusing attention on selected areas of the body, the patient is assisted in localizing painful areas. People who state that they hurt everywhere often begin to realize that some parts of the body are not painful.

Intensity and Quality of Pain

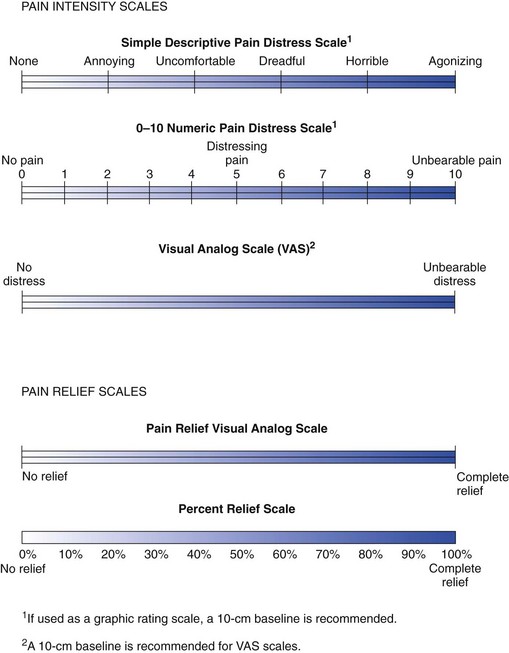

Subjective measurements of pain intensity are more reliable and accurate than observable qualities of pain. Only the patient can determine the amount or severity of pain being experienced. Various visual analog scales (VASs), number rating scales (NRSs), descriptive word scales, and other measures have been designed to help patients communicate the magnitude or severity of pain and to help nurses quantify the pain (Fig. 5-3).

Verbal descriptive scales typically group words such as “none,” “moderate,” or “severe” and permit an intensity rating of pain. However, the 0-to-10 or 1-to-10 NRS is used most commonly in clinical practice for adult patients who can communicate in English (see Fig. 5-3). For culturally diverse patients with language barriers, the Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale (pain rating scale of smile to frown) may be helpful. This scale is also used for children, older adults, and developmentally disabled populations (Flaherty, 2008).

Assessing Pain in Cognitively Impaired or Critically Ill Nonverbal Patients

In 2006, the American Society for Pain Management Nursing published its classic position statement on evidence-based recommendations when performing pain assessments for nonverbal patients (Herr et al., 2006). Five general recommendations for pain assessment were presented:

• Use self-report (when possible).

• Search for potential causes of pain.

• Recognize the value of surrogate reporting (e.g., family member or life partner).

Nurses and other clinicians have recently been researching assessment tools to measure observable nonverbal behaviors that indicate the patient is in pain. A variety of valid and reliable tools are published in the literature (Federico, 2009). Most of them are designed to be used for patients with severe dementia. Examples of commonly used assessment tools that can be used for patients with acute confusion or dementia include:

• Pain Assessment Tool for Confused Older Adults (used for hospitalized patients)

• Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia Scale (PAINAD)

• Discomfort in Dementia of the Alzheimer’s Type Scale

• Faces, Legs, Activity, Crying and Consolability Tool

• Non-Communicative Patient’s Pain Assessment Instrument (NOPPAIN)

The Checklist of Nonverbal Pain Indicators is based on the work of The American Geriatrics Society (AGS) Panel on Persistent Pain in Older Persons. The panel found six common pain indicators that you can observe and document to indicate pain (AGS, 2002):

• Facial expression (e.g., grimacing, crying)

• Verbalizations or vocalizations (e.g., screaming)

• Body movements (e.g., restlessness)

• Changes in interpersonal interactions

• Changes in activity patterns or routines

• Mental status changes (e.g., confusion, increased confusion)

Health Promotion and Maintenance

A. Ask her family or caregiver what they think her pain level is.

B. Ask the client what her pain level is.

C. Observe her body movements and facial expression.

D. Assume she has pain and give her a bolus of PCA morphine.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree