Pain Management

Objectives

• Discuss common misconceptions about pain.

• Describe the physiology of pain.

• Identify components of the pain experience.

• Explain how the physiology of pain relates to selecting interventions for pain relief.

• Describe the components of pain assessment.

• Be able to perform an assessment of a patient experiencing pain.

• Explain how cultural factors influence the pain experience.

• Describe guidelines for selecting and individualizing pain interventions.

• Explain various pharmacological approaches to treating pain.

• Describe applications for use of nonpharmacological pain interventions.

• Discuss nursing implications for administering analgesics.

• Identify barriers to effective pain management.

Key Terms

Acupressure, p. 980

Acute pain, p. 965

Addiction, p. 988

Adjuvants, p. 981

Analgesics, p. 981

Biofeedback, p. 978

Breakthrough pain, p. 986

Chronic pain, p. 965

Cutaneous stimulation, p. 978

Drug tolerance, p. 988

Epidural analgesia, p. 985

Guided imagery, p. 978

Idiopathic pain, p. 966

Local anesthesia, p. 985

Modulation, p. 964

Neurotransmitters, p. 963

Nociceptor, p. 963

Opioids, p. 981

Pain threshold, p. 964

Pain tolerance, p. 964

Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA), p. 983

Perception, p. 963

Perineural infusion, p. 984

Physical dependence, p. 988

Placebos, p. 989

Prostaglandins, p. 963

Pseudoaddiction, p. 965

Regional anesthesia, p. 985

Relaxation, p. 978

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), p. 981

Transduction, p. 963

Transmission, p. 963

![]()

Everyone eventually experiences some type or degree of pain. Although it is the most common reason that people seek health care, pain is not well understood. A person in pain feels distress or suffering and seeks relief. As the nurse you cannot see or feel the patient’s pain. It is purely subjective. No two people experience pain in the same way, and no two painful events create identical responses or feelings in a person. The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defines pain as “an unpleasant, subjective sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage” (IASP, 2010).

Congress declared 2000 to 2010 the Decade of Pain Control and Research, yet pain continues to be a leading public health problem in the United States. Providing pain relief is a basic human right and is in the Pain Care Bill of Rights (APF, 2007). According to the American Bar Association (2009), pain management is a basic right of people who are seriously ill. Nurses are legally and ethically responsible for managing pain and relieving suffering.

When caring for patients in pain, consider the nurse-patient relationship, patient advocacy, patient empowerment, compassion, and respect (Vaartio et al., 2009). Caring for patients in pain requires recognition that pain can and should be relieved. Effective communication among the patient, family, and professional caregivers is essential to achieve adequate pain management. You show respect for a patient in pain when you accept McCaffery’s classic definition: “Pain is whatever the experiencing person says it is, existing whenever he says it does” (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011). Effective pain management improves quality of life; reduces physical discomfort; promotes earlier mobilization and return to previous activity levels; results in fewer hospital and clinic visits; and decreases hospital lengths of stay, resulting in lower health care costs.

Scientific Knowledge Base

Nature of Pain

The pain experience is complex, involving physical, emotional, and cognitive components. Pain is subjective and highly individualized. Its stimulus is physical and/or mental in nature. Pain uses a person’s energy. It interferes with personal relationships and influences the meaning of life. You cannot measure it objectively. Only the patient knows whether pain is present and how the experience feels. It is not the responsibility of patients to prove that they are in pain; it is a nurse’s responsibility to accept their report (APS, 2003).

Physiology of Pain

There are four physiological processes of nociceptive (normal) pain: transduction, transmission, perception, and modulation (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011). A patient in pain cannot discriminate among the processes. Understanding each process helps you recognize factors that cause pain, symptoms that accompany it, and the rationale for selected therapies.

Thermal, chemical, or mechanical stimuli usually cause pain. Transduction converts energy produced by these stimuli into electrical energy Transduction begins in the periphery when a pain-producing stimulus sends an impulse across a sensory peripheral pain nerve fiber (nociceptor), initiating an action potential. Once transduction is complete, transmission of the pain impulse begins.

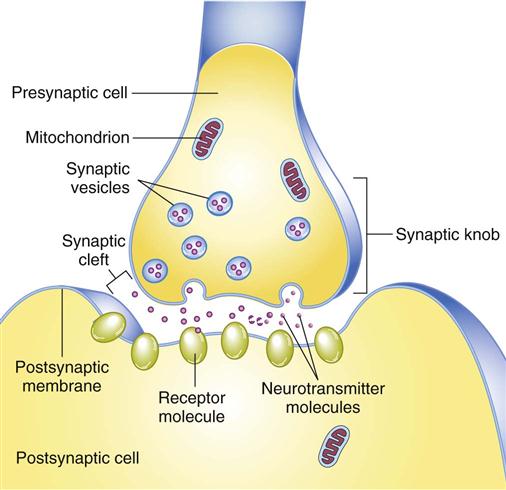

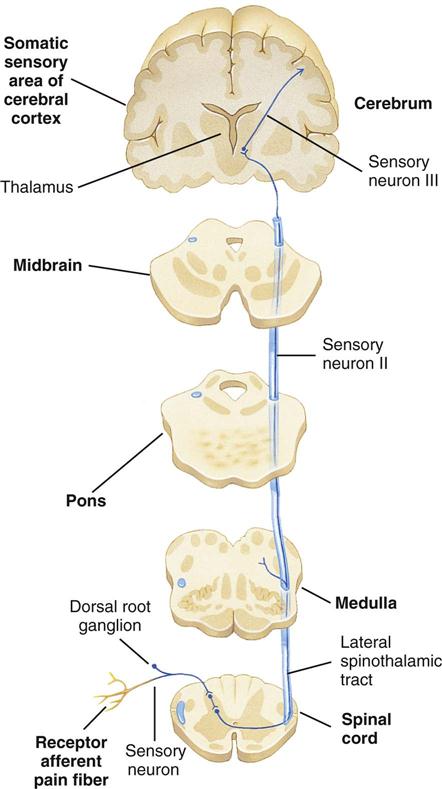

Cellular damage caused by thermal, mechanical, or chemical stimuli results in the release of excitatory neurotransmitters such as prostaglandins, bradykinin, substance P, and histamine (Box 43-1). These pain-sensitizing substances surround the pain fibers in the extracellular fluid, creating an “inflammatory soup,” spreading the pain message and causing an inflammatory response (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011). The pain stimulus enters the spinal cord via the dorsal horn and travels one of several routes until ending within the gray matter of the spinal cord. At the dorsal horn substance P is released, causing a synaptic transmission from the afferent (sensory) peripheral nerve to spinothalamic tract nerves, which cross to the opposite side (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011) (Fig. 43-1).

Nerve impulses resulting from the painful stimulus travel along afferent (sensory) peripheral nerve fibers. Two types of peripheral nerve fibers conduct painful stimuli: the fast, myelinated A-delta fibers and the very small, slow, unmyelinated C fibers. The A fibers send sharp, localized, and distinct sensations that specify the source of the pain and detect its intensity. The C fibers relay impulses that are poorly localized, burning, and persistent. For example, after stepping on a nail, a person initially feels a sharp, localized pain, which is a result of A-fiber transmission. Within a few seconds the pain becomes more diffuse and widespread, until the whole foot hurts because of C-fiber innervations (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011).

Along the spinothalamic tract, pain impulses travel up the spinal cord (Fig. 43-2). After the pain impulse ascends the spinal cord, the thalamus transmits information to higher centers in the brain, including the reticular formation, limbic system, somatosensory cortex, and association cortex. Once a pain stimulus reaches the cerebral cortex, the brain interprets the quality of the pain and processes information from past experience, knowledge, and cultural associations in the perception of the pain (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011). Perception is the point at which a person is aware of pain. The somatosensory cortex identifies the location and intensity of pain, whereas the association cortex, primarily the limbic system, determines how a person feels about it. There is no single pain center.

As a person becomes aware of pain, a complex reaction occurs. Psychological and cognitive factors interact with neurophysiological ones in the perception of pain. Perception gives awareness and meaning to pain, resulting in a reaction. The reaction to pain includes the physiological and behavioral responses that occur after an individual perceives pain (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011).

Once the brain perceives pain, there is a release of inhibitory neurotransmitters (see Box 43-1) such as endogenous opioids, serotonin, norepinephrine, and gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA), which work to hinder the transmission of pain and help produce an analgesic effect (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011). This inhibition of the pain impulse is the fourth and last phase of the nociceptive process known as modulation (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011).

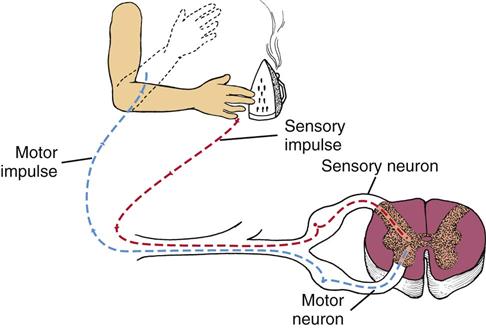

A protective reflex response also occurs with pain reception (Fig. 43-3). A-delta fibers send sensory impulses to the spinal cord, where they synapse with spinal motor neurons. The motor impulses travel via a reflex arc along efferent (motor) nerve fibers back to a peripheral muscle near the site of stimulation, thus bypassing the brain. Contraction of the muscle leads to a protective withdrawal from the source of pain. For example, when you accidentally touch a hot iron, you feel a burning sensation, but your hand also reflexively withdraws from the surface of the iron.

Gate-Control Theory of Pain

Melzack and Wall’s gate-control theory (1965) first suggested that pain has emotional and cognitive components in addition to a physical sensation. According to this theory, gating mechanisms located along the central nervous system regulate or even block pain impulses. Pain impulses pass through when a gate is open and are blocked when a gate is closed. Closing the gate is the basis for nonpharmacological pain-relief interventions. You gain a useful conceptual framework for pain management by understanding the physiological, emotional, and cognitive influences on the gates. For example, factors such as stress and exercise increase the release of endorphins, often raising an individual’s pain threshold (the point at which a person feels pain). Because the amount of circulating substances varies with every individual, the response to pain varies.

Physiological Responses

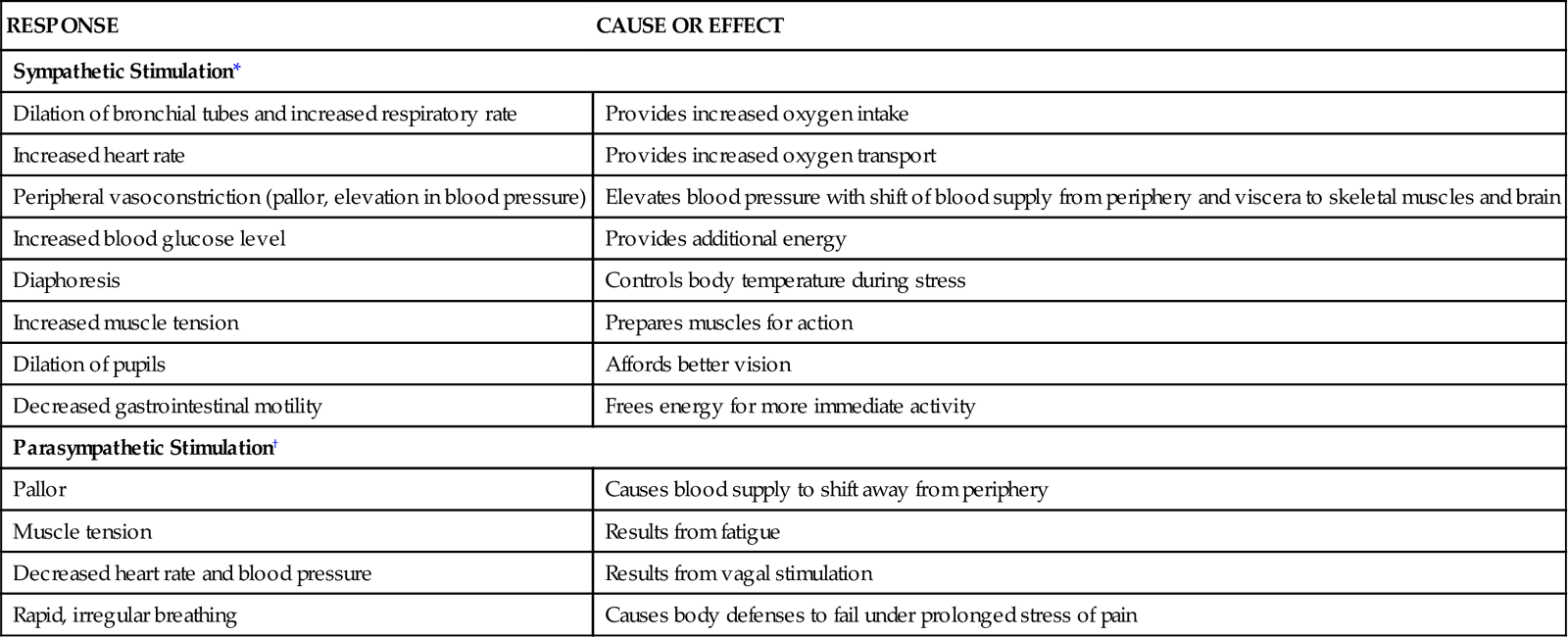

As pain impulses ascend the spinal cord toward the brainstem and thalamus, the stress response stimulates the autonomic nervous system. Pain of low to moderate intensity and superficial pain elicit the fight-or-flight reaction of the general adaptation syndrome (see Chapter 37). Stimulation of the sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system results in physiological responses (Table 43-1). Continuous, severe, or deep pain typically involving the visceral organs (e.g., with a myocardial infarction or colic from gallbladder or renal stones) activates the parasympathetic nervous system. Sustained physiological responses to pain sometimes seriously harm individuals. Except in cases of severe traumatic pain, which causes a person to go into shock, most people adapt to their pain, and their physical signs return to normal. Thus patients in pain do not always have changes in their vital signs. Changes in vital signs more often indicate problems other than pain.

TABLE 43-1

Physiological Reactions to Pain

| RESPONSE | CAUSE OR EFFECT |

| Sympathetic Stimulation* | |

| Dilation of bronchial tubes and increased respiratory rate | Provides increased oxygen intake |

| Increased heart rate | Provides increased oxygen transport |

| Peripheral vasoconstriction (pallor, elevation in blood pressure) | Elevates blood pressure with shift of blood supply from periphery and viscera to skeletal muscles and brain |

| Increased blood glucose level | Provides additional energy |

| Diaphoresis | Controls body temperature during stress |

| Increased muscle tension | Prepares muscles for action |

| Dilation of pupils | Affords better vision |

| Decreased gastrointestinal motility | Frees energy for more immediate activity |

| Parasympathetic Stimulation† | |

| Pallor | Causes blood supply to shift away from periphery |

| Muscle tension | Results from fatigue |

| Decreased heart rate and blood pressure | Results from vagal stimulation |

| Rapid, irregular breathing | Causes body defenses to fail under prolonged stress of pain |

*Pain of low-to-moderate intensity and superficial pain.

Behavioral Responses

If left untreated or unrelieved, pain significantly alters quality of life. It usually interferes with every aspect of a person’s life, which supports why effective pain management is essential. It threatens physical and psychological well-being. Some patients choose not to report pain if they believe that it inconveniences others or if it signals loss of self-control, and some endure severe pain without assistance. Encourage your patients to accept pain-relieving measures so they remain active and continue to maintain daily activities. In contrast, other patients seek relief before pain occurs, having learned that prevention is easier than treatment. A patient’s ability to tolerate pain significantly influences your perceptions of the degree of the patient’s discomfort. Patients who have a low pain tolerance (level of pain a person is willing to accept) are sometimes inaccurately perceived as complainers. Teach patients the importance of reporting their pain sooner rather than later.

Body movements and facial expressions indicating pain include clenched teeth, holding the painful area, bent posture, and grimacing. Some patients cry or moan, are restless, or make frequent requests of a nurse. You soon learn to recognize patterns of behavior that reflect pain. This becomes especially important in patients who are unable to report their pain such as the cognitively impaired. However, lack of pain expression does not indicate that the patient is not experiencing pain (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011).

Types of Pain

Pain is categorized by duration (acute or chronic) or pathological condition (e.g., cancer or neuropathic).

Acute/Transient Pain

Acute pain is protective, has an identifiable cause, is of short duration, and has limited tissue damage and emotional response. It eventually resolves, with or without treatment, after an injured area heals. Because acute pain has a predictable ending (healing) and an identifiable cause, health team members are usually willing to treat it aggressively. Unrelieved acute pain can progress to chronic pain (Kehlet et al., 2006).

Acute pain seriously threatens a patient’s recovery by resulting in prolonged hospitalization, increased risks of complications from immobility (see Chapter 47), and delayed rehabilitation. Physical and psychological progress is delayed as long as acute pain persists because a patient focuses all energy on pain relief. Efforts aimed at teaching and motivating the patient toward self-care are often hampered until the pain is successfully managed. Complete pain relief is not always achievable, but reducing pain to a tolerable level is realistic. Thus a primary nursing goal is to provide pain relief that allows patients to participate in their recovery.

Chronic/Persistent Noncancer Pain

Unlike acute pain, chronic pain is not protective and thus serves no purpose. Chronic pain lasts longer than 6 months and is constant or recurring with a mild-to-severe intensity (Ackley and Ladwig, 2011). It does not always have an identifiable cause and leads to great personal suffering. Examples of chronic noncancer pain include arthritis, low back pain, myofascial pain, headache, and peripheral neuropathy. Chronic pain is usually non–life threatening. Sometimes an injured area healed long ago, yet the pain is ongoing and does not respond to treatment.

The possible unknown cause of chronic pain, combined with the unrelenting nature and uncertainty of its duration, frustrates a patient, frequently leading to psychological depression and even suicide. Chronic pain is a major cause of psychological and physical disability, leading to problems such as job loss, inability to perform simple daily activities, sexual dysfunction, and social isolation.

The person with chronic noncancer pain often does not show obvious symptoms and does not adapt to the pain. Rather, he or she seems to suffer more with time because of physical and mental exhaustion. Associated symptoms of chronic pain include fatigue, insomnia, anorexia, weight loss, apathy, hopelessness, and anger. Chronic pain creates the uncertainty of how one will feel from day to day. If there is no objective evidence to confirm the existence of pain, the “burden of proof” lies with the patient (Shaw, 2006). Health care workers are usually less willing to treat chronic noncancer pain with opioids, although a policy statement supports the use of opioids for it (Chou et al., 2009). In addition, the American Society of Anesthesiologists (2010) developed “Practice Guidelines for Chronic Pain Management,” which includes the use of opioids. Often a person with chronic pain who consults with numerous health care providers is labeled a drug seeker, when he or she is actually seeking adequate pain relief. This situation is called pseudoaddiction. Nurses need to discourage patients from having multiple health care providers for treating pain and refer them to pain specialists. Pain centers offer a holistic approach to chronic pain using both nonpharmacological and pharmacological strategies for pain management (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011).

Chronic Episodic Pain

Pain that occurs sporadically over an extended period of time is episodic pain. Pain episodes last for hours, days, or weeks. Examples are migraine headaches and pain related to sickle cell disease (Gruener and Lande, 2006).

Cancer Pain

Not all patients with cancer experience pain. For those who do, as many as 90% are able to have their pain managed with relatively simple means (Lehne, 2010). Some patients with cancer experience acute and/or chronic pain. The pain is nociceptive and/or neuropathic. Cancer pain is usually caused by tumor progression and related pathological processes, invasive procedures, toxicities of treatment, infection, and physical limitations. A patient senses pain at the actual site of the tumor or distant to the site, called referred pain. Assess reports of new pain by a patient with existing pain. Although the treatment of cancer pain has improved, undertreatment of cancer pain continues. Approximately 70% to 90% of patients with advanced cancer experience pain. Sixty percent of them report moderate-to-severe pain (Maxwell et al., 2005).

Pain by Inferred Pathological Process

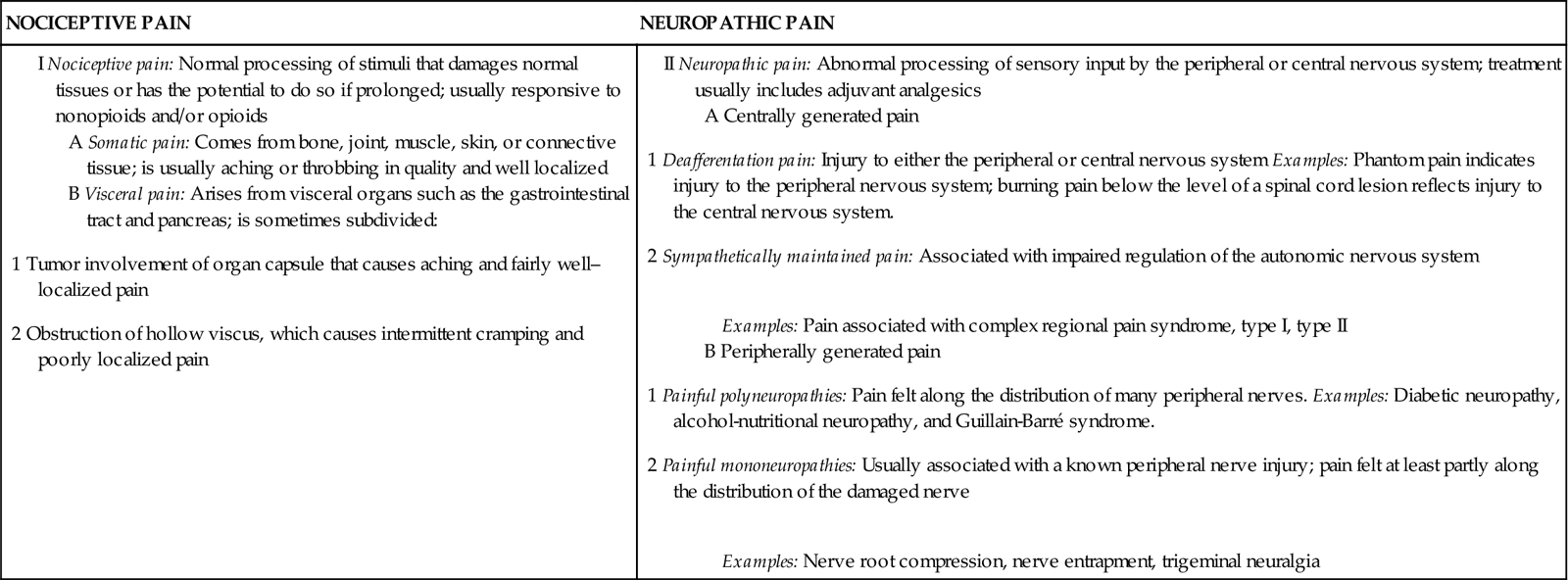

Identifying the cause of pain is the first step in successful treatment. Nociceptive pain includes somatic (musculoskeletal) and visceral (internal organ) pain. Neuropathic pain arises from abnormal or damaged pain nerves (Table 43-2). Each of these pathological processes has distinct pain characteristics. The pain assessment section discusses these further.

TABLE 43-2

Classification of Pain by Inferred Pathology

From Pasero C, McCaffery M: Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, St Louis, 2011, Mosby.

Idiopathic Pain

Idiopathic pain is chronic pain in the absence of an identifiable physical or psychological cause or pain perceived as excessive for the extent of an organic pathological condition. An example of idiopathic pain is complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS). Research is needed to better identify the causes of idiopathic pain, thus leading to a more effective treatment (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011).

Nursing Knowledge Base

Nursing knowledge of pain mechanisms and interventions continues to grow through nursing research. This section explores factors that influence the pain experience.

Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs

Attitudes of nurses and other health care providers affect pain management. The traditional medical model of illness generates attitudes about pain. This model suggests that physical problems result from physical causes. Thus pain is a physical response to organic dysfunction. When there is no obvious source of pain (e.g., the patient with chronic low back pain or neuropathies), health care providers sometimes stereotype pain sufferers as malingerers, complainers, or difficult patients.

Studies of nurses’ attitudes regarding pain management show that a nurse’s personal opinion about a patient’s report of pain affects pain assessment and titration of opioid doses. The amount of analgesia administered varies based on whether a patient is grimacing or smiling during the nurse’s assessment (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011). Nurses with more than 6 years of work experience, higher job motivation, and perceived higher levels of pain-care skills in themselves often use more patient advocacy skills in providing pain management for patients (Vaartio et al., 2009).

Nurses’ assumptions about patients in pain seriously limit their ability to offer pain relief. Biases based on culture, education, and experience influence everyone. Too often nurses allow misconceptions about pain (Box 43-2) to affect their willingness to intervene. Some nurses avoid acknowledging a patient’s pain because of their own fear and denial. They do not believe a patient’s report of pain if he or she does not look in pain. You are entitled to your personal beliefs; however, you must accept a patient’s report of pain and act according to professional guidelines, standards, position statements, policies and procedures, and evidence-based research findings (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011).