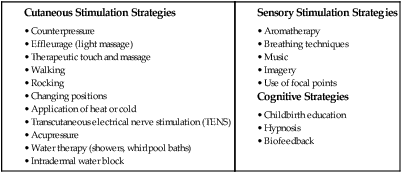

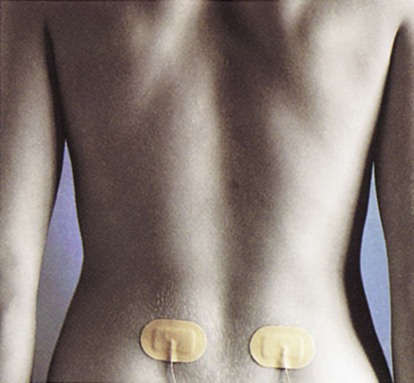

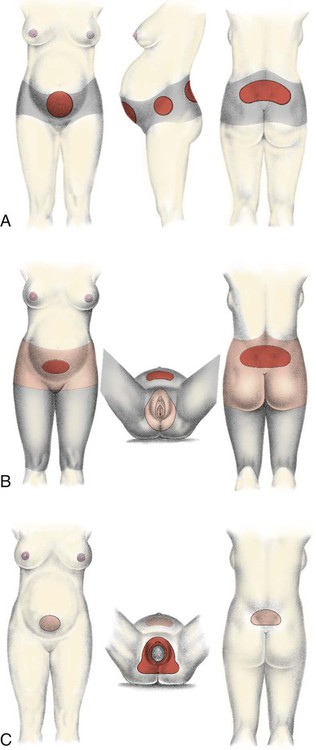

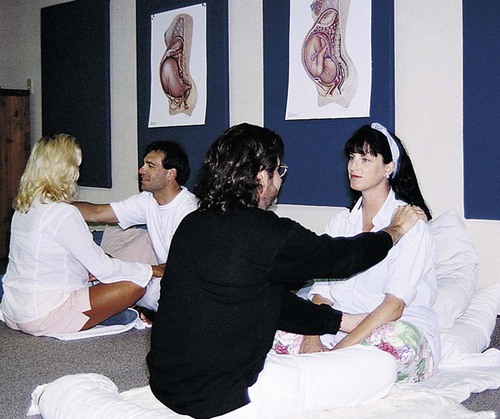

On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Describe breathing and relaxation techniques used for each stage of labor. • Identify nonpharmacologic strategies to enhance relaxation and decrease pain during labor. • Compare pharmacologic methods used to relieve pain in different stages of labor and for vaginal or cesarean birth. • Describe nursing responsibilities appropriate in providing care for a woman receiving analgesia and anesthesia during labor. The pain and discomfort of labor have two origins—visceral and somatic. During the first stage of labor, uterine contractions cause cervical dilation and effacement. Uterine ischemia (decreased blood flow and therefore local oxygen deficit) results from compression of the arteries supplying the myometrium during uterine contractions. Pain impulses during the first stage of labor are transmitted via the T10 to T12 and L1 spinal nerve segments and accessory lower thoracic and upper lumbar sympathetic nerves. These nerves originate in the uterine body and cervix (Blackburn, 2013). The pain from distention of the lower uterine segment, stretching of cervical tissue as it effaces and dilates, pressure and traction on adjacent structures (e.g., uterine tubes, ovaries, ligaments) and nerves, and uterine ischemia during the first stage of labor is visceral pain. It is located over the lower portion of the abdomen. Referred pain occurs when pain that originates in the uterus radiates to the abdominal wall, lumbosacral area of the back, iliac crests, gluteal area, thighs, and lower back (Blackburn, 2013; Zwelling, Johnson, and Allen, 2006). During most of the first stage of labor, the woman usually has discomfort only during contractions and is free of pain between contractions. Some women, especially those whose fetus is in a posterior position, experience continuous contraction-related low back pain, even in the interval between contractions. As labor progresses and pain becomes more intense and persistent, women become fatigued and discouraged, often experiencing difficulty coping with contractions (Creehan, 2008; Zwelling, Johnson, and Allen, 2006). • Distention and traction on the peritoneum and uterocervical supports during contractions • Pressure against the bladder and rectum • Stretching and distention of perineal tissues and the pelvic floor to allow passage of the fetus • Lacerations of soft tissue (e.g., cervix, vagina, and perineum) As women concentrate on the work of bearing down to give birth to their baby, they may report a decrease in pain intensity (Blackburn, 2013; Creehan, 2008). Pain impulses during the second stage of labor are transmitted via the pudendal nerve through S2 to S4 spinal nerve segments and the parasympathetic system (Blackburn, 2013). Pain experienced during the third stage of labor and the afterpains of the early postpartum period are uterine, similar to the pain experienced early in the first stage of labor. Areas of pain during labor are shown in Fig. 14-1. Pain tolerance refers to the level of pain a laboring woman is willing to endure. When this level is exceeded, she will seek measures to relieve the pain. Factors that influence a woman’s pain tolerance level and her request for pharmacologic pain relief measures include her desire for a natural, vaginal birth; her preparation for childbirth; the nature of her support during labor; and her willingness and ability to participate in nonpharmacologic measures for comfort (Creehan, 2008). Pain during childbirth is unique to each woman. How she perceives or interprets that pain is influenced by a variety of physiologic, psychologic, emotional, social, cultural, and environmental factors (Zwelling, Johnson, and Allen, 2006). A variety of physiologic factors can affect the intensity of childbirth pain. Women with a history of dysmenorrhea may experience increased pain during childbirth as a result of higher prostaglandin levels. Back pain associated with menstruation also may increase the likelihood of contraction-related low back pain. Other physical factors that affect pain intensity include fatigue, the interval and duration of contractions, fetal size and position, rapidity of fetal descent, and maternal position (Zwelling, Johnson, and Allen, 2006). Beta (β) endorphins are endogenous opioids secreted by the pituitary gland that act on the central and peripheral nervous systems to reduce pain. The level of β endorphins increases during pregnancy and birth in humans. β endorphins are associated with feelings of euphoria and analgesia. The pain threshold may rise as β endorphin levels increase, enabling women in labor to tolerate acute pain (Blackburn, 2013). The population of pregnant women reflects the increasingly multicultural nature of society in the United States. As nurses care for women and families from a variety of cultural backgrounds, they must have knowledge and understanding of how culture mediates pain. Although all women expect to experience at least some pain and discomfort during childbirth, it is their culture and religious belief system that determines how they will perceive, interpret, and respond to and manage the pain. For example, women with strong religious beliefs often accept pain as a necessary and inevitable part of bringing a new life into the world (Callister, Khalaf, Semenic, et al., 2003). An understanding of the beliefs, values, expectations, and practices of various cultures will narrow the cultural gap and help the nurse assess the laboring woman’s pain experience more accurately. The nurse can then provide appropriate, culturally sensitive care by using pain relief measures that preserve the woman’s sense of control and self-confidence (see Cultural Competence box). Recognize that although a woman’s behavior in response to pain may vary according to her cultural background, it may not accurately reflect the intensity of the pain she is experiencing. Assess the woman for the physiologic effects of pain, and listen to the words she uses to describe the sensory and affective qualities of her pain (see Community Focus box). Anxiety is commonly associated with increased pain during labor. Mild anxiety is considered normal for a woman during labor and birth. However, excessive anxiety and fear cause more catecholamine secretion, which increases the stimuli to the brain from the pelvis because of decreased blood flow and increased muscle tension. This action, in turn, magnifies pain perception. Thus as anxiety and fear heighten, muscle tension increases, the effectiveness of uterine contractions decreases, the experience of discomfort increases, and a cycle of increased fear and anxiety begins (Blackburn, 2013). Ultimately this cycle will slow the progress of labor. The woman’s confidence in her ability to cope with pain will be diminished, potentially resulting in reduced effectiveness of the pain relief measures being used. Sensory pain for nulliparous women is often greater than that for multiparous women during early labor (dilation less than 5 cm) because their reproductive tract structures are less supple. During the transition phase of the first stage of labor and during the second stage of labor, multiparous women may experience greater sensory pain than nulliparous women because their more supple tissue increases the speed of fetal descent and thereby intensifies pain. The firmer tissue of nulliparous women results in a slower, more gradual descent. Affective pain is usually greater for nulliparous women throughout the first stage of labor but decreases for both nulliparous and multiparous women during the second stage of labor (Lowe, 2002). Parity may also influence the perception of labor pain because nulliparous women often have longer labors and therefore greater fatigue. Fatigue and sleep deprivation magnify pain. Most women have a decrease in quality of sleep over the last few days of pregnancy, and the spontaneous onset of labor occurs most often during the night (Beebe and Lee, 2007). Thus many women have an increased perception of the intensity of pain during labor. Current evidence indicates that a woman’s satisfaction with her labor and birth experience is determined by how well her personal expectations of childbirth were met and the quality of support and interaction she received from her caregivers (Box 14-1). In addition, satisfaction is influenced by the degree to which she was able to stay in control of her labor and to participate in decision making regarding her labor, including the pain relief measures to be used (Albers, 2007; Zwelling, Johnson, and Allen, 2006). The value of the continuous supportive presence of a person (e.g., doula, childbirth educator, family member, friend, nurse, or partner) during labor who provides physical comforting, facilitates communication, and offers information and guidance to the woman in labor has long been known. Emotional support is demonstrated by giving praise and reassurance and conveying a positive, calm, and confident demeanor when caring for the woman in labor (Creehan, 2008). It is interesting to note that research findings have concluded that a more positive effect is achieved when the continuous support is provided by people who are not hospital staff members (Hodnett, Gates, Hofmeyr, et al., 2011). The quality of the environment can influence pain perception and the laboring woman’s ability to cope with her pain. Environment includes the individuals present (e.g., how they communicate, their philosophy of care including a belief in the value of nonpharmacologic pain relief measures, practice policies, and quality of support) and the physical space in which the labor occurs (Creehan, 2008; Zwelling, Johnson, and Allen, 2006). Women usually prefer to be cared for by familiar caregivers in a comfortable, homelike setting. The environment should be safe and private, allowing a woman to feel free to be herself as she tries out different comfort measures. Stimuli such as light, noise, and temperature should be adjusted according to her preferences. The environment should have space for movement and equipment such as birth balls. Comfortable chairs, tubs, and showers should be readily available to facilitate participation in a variety of nonpharmacologic pain relief measures. The familiarity of the environment can be enhanced by bringing items from home such as pillows, objects for a focal point, music, and DVDs. With the increasing use of epidural analgesia, nurses may be less likely to encourage women to use nonpharmacologic measures, in part because these methods may be viewed as more complex and time consuming than monitoring a woman receiving an epidural. In addition, new nurses may not have had the opportunity to develop skill in the implementation of these methods. It is imperative that perinatal nurses develop a commitment to and expertise in using a variety of nonpharmacologic pain relief strategies in order for women in labor to be comfortable using them. Although research data to support the effectiveness of many of these nonpharmacologic measures are limited, there are sufficient reports of their benefits from women and health care providers to recommend that nurses encourage their use (Creehan, 2008). The analgesic effect of many nonpharmacologic measures is comparable to or even superior to opioids that are administered parenterally (Box 14-2). Relaxation or reduction of body tension is a technique suggested by virtually all childbirth education organizations. Learning relaxation in childbirth education classes can help couples with the stresses of pregnancy, childbirth, and adjustment to parenting and can be a form of stress management throughout life (Fig. 14-2). Evidence suggests that relaxation may improve the management of labor pain (Jones, Othman, Dowswell, et al., 2012). Relaxation is ideally combined with activity such as walking, slow dancing, rocking, and position changes that help the baby rotate through the pelvis. Rhythmic motion stimulates mechanoreceptors in the brain, which decreases pain perception. The nurse can assist the woman by providing a quiet and relaxed environment, offering cues as needed, and recognizing signs of tension (e.g., frowning, change in tone of voice, clenching of fists). A relaxed environment for labor is created by controlling sensory stimuli (e.g., light, noise, temperature) and reducing interruptions. Nurses should remain calm and unhurried in their approach and sit rather than stand at the bedside whenever possible (Creehan, 2008). Different approaches to childbirth preparation stress varying breathing techniques to provide distraction, thereby reducing the perception of pain and helping the woman maintain control throughout contractions. In the first stage of labor, such breathing techniques can promote relaxation of the abdominal muscles and thereby increase the size of the abdominal cavity. This lessens discomfort generated by friction between the uterus and abdominal wall during contractions. Because the muscles of the genital area also become more relaxed, they do not interfere with fetal descent. In the second stage, breathing is used to increase abdominal pressure and thereby assist in expelling the fetus. Breathing also can be used to relax the pudendal muscles to prevent precipitate expulsion of the fetal head (Fig. 14-3). For couples who have prepared for labor by practicing relaxing and breathing techniques, a simple review with occasional reminders may be all that is necessary to help them along. For those who have had no preparation, instruction and practice in simple breathing and relaxation techniques can be given early in labor and often is surprisingly successful. Nurses can also model breathing techniques and breathe in synchrony with the woman and her partner. Motivation is high and readiness to learn is enhanced by the reality of labor (see Critical Thinking Case Study). Various breathing techniques can be used for controlling pain during contractions (Box 14-3). The nurse needs to determine what, if any, techniques the laboring couple know before giving them instruction. Simple patterns are more easily learned. Paced breathing is most associated with prepared childbirth and includes slow-paced, modified-paced, and patterned-paced breathing (pant-blow) techniques. Each labor is different, and nursing support includes assisting couples to adapt breathing techniques to their individual labor experience. All patterns begin with a deep, relaxing, cleansing breath to “greet the contraction” and end with another deep breath exhaled to “gently blow the contraction away.” These deep breaths ensure adequate oxygen for mother and baby and signal that a contraction is beginning or has ended. As the breath is exhaled, respiratory and voluntary muscles relax (Creehan, 2008). In general, slow-paced breathing is performed at approximately half the woman’s normal breathing rate and is initiated when she can no longer walk or talk through contractions. The woman should take no fewer than three or four breaths per minute. Slow-paced breathing aids in relaxation and provides optimum oxygenation. The woman should continue to use this technique for as long as it is effective in reducing the perception of pain and maintaining control. As contractions increase in frequency and intensity, the woman often needs to change to a more complex breathing technique, which is shallower and faster than her normal rate of breathing but should not exceed twice her resting respiratory rate. This modified-paced breathing pattern requires that she remain alert and concentrate more fully on breathing, thus blocking more painful stimuli than the simpler slow-paced breathing pattern (Perinatal Education Associates, 2008 [www.birthsource.com]). The most difficult time to maintain control during contractions comes during the transition phase of the first stage of labor, when the cervix dilates from 8 cm to 10 cm. Even for the woman who has prepared for labor, concentration on breathing techniques is difficult to maintain. Patterned-paced (pant-blow) breathing is suggested during this phase. It is performed at the same rate as modified-paced breathing and consists of panting breaths combined with soft blowing breaths at regular intervals. The patterns may vary (i.e., pant, pant, pant, pant, blow [4 : 1 pattern] or pant, pant, pant, blow [3 : 1 pattern]) (Perinatal Education Associates, 2008). An undesirable reaction to this type of breathing is hyperventilation. The woman and her support person must be aware of and watch for symptoms of the resultant respiratory alkalosis: lightheadedness, dizziness, tingling of the fingers, or circumoral numbness. Respiratory alkalosis may be eliminated by having the woman breathe into a paper bag held tightly around her mouth and nose. This enables her to rebreathe carbon dioxide and replace the bicarbonate ions. The woman also can breathe into her cupped hands if no bag is available. Maintaining a breathing rate that is no more than twice the normal rate will lessen chances of hyperventilation. The partner can help the woman maintain her breathing rate with visual, tactile, or auditory cues. As the fetal head reaches the pelvic floor, the woman may feel the urge to push and may automatically begin to exert downward pressure by contracting her abdominal muscles. During second-stage pushing, the woman should find a breathing pattern that is relaxing and feels good to her and is safe for her baby. Any regular or rhythmic breathing that avoids prolonged breath holding during pushing should maintain a good oxygen flow to the fetus (Perinatal Education Associates, 2008). Counterpressure is steady pressure applied by a support person to the sacral area with a firm object (e.g., tennis ball) or the fist or heel of the hand. Pressure can also be applied to both hips (double hip squeeze) or to the knees (Creehan, 2008). Application of counterpressure helps the woman cope with the sensations of internal pressure and pain in the lower back. It is especially helpful when back pain is caused by pressure of the occiput against spinal nerves when the fetal head is in a posterior position. Counterpressure lifts the occiput off these nerves, thereby providing pain relief. The support person will need to be relieved occasionally because application of counterpressure is hard work. Touch and massage have been an integral part of the traditional care process for women in labor. A variety of massage techniques have been shown to be safe and effective during labor (Gilbert, 2011; Zwelling, Johnson, and Allen, 2006). Therapeutic touch (TT) uses the concept of energy fields within the body called prana. Prana are thought to be deficient in some people who are in pain. TT uses laying-on of hands by a specially trained person to redirect energy fields associated with pain. Research has demonstrated the effectiveness of TT to enhance relaxation, reduce anxiety, and relieve pain (Aghabati, Mohammadi, and Pour Esmaiel, 2010); however, little is known about the use or effectiveness of TT for relieving labor pain. Head, hand, back, and foot massage may be very effective in reducing tension and enhancing comfort. Some evidence suggests that massage may improve management of labor pain (Jones, Othman, Dowswell, et al., 2012). Hand and foot massage may be especially relaxing in advanced labor when hyperesthesia limits a woman’s tolerance for touch on other parts of her body. The woman and her partner should be encouraged to experiment with different types of massage during pregnancy to determine what might feel best and be most relaxing during labor. Cold application such as cold cloths, frozen gel packs, or ice packs applied to the back, the chest, and/or the face during labor may be effective in increasing comfort when the woman feels warm. They also may be applied to areas of musculoskeletal pain. Cooling relieves pain by reducing the muscle temperature and relieving muscle spasms (Creehan, 2008). However, a woman’s culture may make the use of cold during labor unacceptable. Heat and cold may be used alternately for a greater effect. Neither heat nor cold should be applied over ischemic or anesthetized areas because tissues can be damaged. One or two layers of cloth should be placed between the skin and a hot or cold pack to prevent damage to the underlying integument (see Critical Thinking Case Study). Acupressure and acupuncture can be used in pregnancy, in labor, and postpartum to relieve pain and other discomforts. Pressure, heat, or cold is applied to acupuncture points called tsubos. These points have an increased density of neuroreceptors and increased electrical conductivity. Acupressure is said to promote circulation of blood, the harmony of yin and yang, and the secretion of neurotransmitters, thus maintaining normal body functions and enhancing well-being (Tournaire and Theau-Yonneau, 2007). Acupressure is best applied over the skin without using lubricants. Pressure is usually applied with the heel of the hand, fist, or pads of the thumbs and fingers (Fig. 14-4). Tennis balls or other devices also may be used. Pressure is applied with contractions initially and then continuously as labor progresses to the transition phase at the end of the first stage of labor (Tournaire and Theau-Yonneau, 2007). Synchronized breathing by the caregiver and the woman is suggested for greater effectiveness. Acupressure points are found on the neck, the shoulders, the wrists, the lower back including sacral points, the hips, the area below the kneecaps, the ankles, the nails on the small toes, and the soles of the feet. Evidence is insufficient to support the effectiveness of acupressure as a method of pain relief during labor (Smith, Collins, Cyna, et al., 2006). Acupuncture is the insertion of fine needles into specific areas of the body to restore the flow of qi (energy) and to decrease pain, which is thought to be obstructing the flow of energy. Effectiveness may be attributed to the alteration of chemical neurotransmitter levels in the body or to the release of endorphins as a result of hypothalamic activation. Acupuncture should be done by a trained certified therapist, and arranging to have a qualified and credentialed acupuncture provider available during labor and birth may be challenging (Hawkins and Bucklin, 2012). Current evidence indicates that acupuncture may be beneficial for relief of labor pain; however, further study is indicated (Hawkins and Bucklin, 2012; Jones, Othman, Dowswell, et al., 2012). Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) involves the placing of two pairs of flat electrodes on either side of the woman’s thoracic and sacral spine (Fig. 14-5). These electrodes provide continuous low-intensity electrical impulses or stimuli from a battery-operated device. During a contraction, the woman increases the stimulation from low to high intensity by turning control knobs on the device. High intensity should be maintained for at least 1 minute to facilitate release of endorphins. Women describe the resulting sensation as a tingling or buzzing. TENS is most useful for lower back pain during the early first stage of labor. Women tend to rate the device as helpful although its use does not decrease pain. It appears that the electrical impulses or stimuli somehow make the pain less disturbing. No serious safety concerns are associated with the use of TENS (Hawkins and Bucklin, 2012). Bathing, showering, and jet hydrotherapy (whirlpool baths) with warm water (e.g., at or below body temperature) are nonpharmacologic measures that can promote comfort and relaxation during labor (Fig. 14-6). The warm water stimulates the release of endorphins, relaxes fibers to close the gate on pain, promotes better circulation and oxygenation, and helps soften the perineal tissues. Most women find immersion in water to be soothing, relaxing, and comforting. While immersed, they may find it easier to let go and allow labor to take its course (Gilbert, 2011). Some evidence suggests that immersion in water may improve management of labor pain (Jones, Othman, Dowswell, et al., 2012). Before initiating hydrotherapy measures, agency policy should be consulted to determine if the approval of the laboring woman’s primary health care provider is required and if criteria need to be met in terms of the status of the maternal and fetal unit (e.g., stable vital signs and fetal heart rate [FHR] and pattern, and stage of labor). To reduce the risk of a prolonged labor, hydrotherapy is usually initiated when the woman is in active labor, at approximately 5 cm. It is at this time that she may be getting discouraged and will welcome the change that hydrotherapy offers. Remember to preserve her modesty because she may be shy about the exposure of her body when getting into a tub or shower (Creehan, 2008). In addition to pain relief and relaxation, hydrotherapy offers other benefits. If a woman is having “back labor” as the result of an occiput posterior or transverse position, assuming a hands-and-knees or a side-lying position in the tub enhances spontaneous fetal rotation to the occiput anterior position as a result of increased buoyancy. Because less effort is needed to change positions while in the water, women are encouraged to assume upright positions and to alter positions more frequently, facilitating the progress of their labors and helping them cope with labor-associated stressors (Stark, Rudell, and Haus, 2008). When hydrotherapy is in use, FHR monitoring is done by Doppler, fetoscope, or wireless external monitor (see Fig. 14-6, C). Placement of internal electrodes is contraindicated for jet hydrotherapy. There is no limit to the time women can stay in the bath, and often they are encouraged to stay in it as long as desired. However, most women use jet hydrotherapy for 30 to 60 minutes at a time. During the bath, if the woman’s temperature and the FHR increase, if the labor process becomes less effective (e.g., slows or becomes too intense), or if relief of pain is reduced, the woman can come out of the bath and return at a later time. Repeated baths with occasional breaks may be more effective in relieving pain in long labors than extended amounts of time in the water. The temperature of the water should be maintained at 36° to 37° C (96.8° to 98.6° F) with the water covering the woman’s abdomen to gain maximum effect from the hydrostatic pressure and buoyancy of the water. Her shoulders should remain out of the water to facilitate the dissipation of heat (Creehan, 2008). The American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and Newborn has expressed concerns about actual birthing in water because of the lack of research demonstrating its safety. There are rare but reported instances of asphyxia or infection that have occurred during or as a result of underwater birth. This group believes that underwater birth should be considered an experimental procedure, performed only after informed parental consent has been obtained (Hawkins and Bucklin, 2012). Using a shower provides comfort through the application of heat as the handheld shower head is directed to areas of discomfort (see Fig. 14-6, A and B). The coach or partner can participate in this comfort measure by holding and directing the shower head. An intradermal water block involves the injection of small amounts of sterile water (e.g., 0.05 to 0.1 mL) by using a fine-gauge needle (e.g., 25 gauge) into four locations on the lower back to relieve low back pain (Fig. 14-7). It is a simple procedure to perform, and there is evidence that it is effective, perhaps because of the gate-control mechanism (Hawkins and Bucklin, 2012). Other possible explanations for the effectiveness of the intradermal water block are the mechanism of counterirritation (i.e., reducing localized pain in one area by irritating the skin in an area nearby) or an increase in the level of endogenous opioids (endorphins) produced by the injections. Intense stinging will occur for about 20 to 30 seconds after injection, but relief of back pain for up to 2 hours has been reported. The procedure can be repeated although the woman may find that the stinging that occurs with administration creates too much discomfort (Creehan, 2008). Aromatherapy uses oils distilled from plants, flowers, herbs, and trees to promote health and to treat and balance the mind, body, and spirit. These essential oils are highly concentrated, complex essences and are mixed with lotions or creams before they are applied to the skin (e.g., for a back massage). Certain essential oils can tone the uterus, encourage contractions, reduce pain, relieve tension, diminish fear and anxiety, and enhance the feeling of well-being. Lavender, rose, and jasmine oils can promote relaxation and reduce pain. Rose oil also acts as an antidepressant and uterine tonic, whereas jasmine oil strengthens contractions and decreases feelings of panic in addition to reducing pain. Essential oils of bergamot or rosemary can be diffused or used in a massage oil to relieve exhaustion (Gilbert, 2011; Tournaire and Theau-Yonneau, 2007; Walls, 2009). Oils may also be used by adding a few drops to a warm bath, to warm water used for soaking compresses that can be applied to the body, or to an aromatherapy lamp to vaporize a room. Drops of essential oils can be put on a pillow or on a woman’s brow or palms or used as an ingredient in creating massage oil (Simkin and Bolding, 2004; Walls, 2009; Zwelling, Johnson, and Allen, 2006). Certain odors or scents can evoke pleasant memories and feelings of love and security. As a result, it would be helpful for a woman to choose the scents that she will use (Trout, 2004). There is insufficient evidence to support the effectiveness of aromatherapy for pain relief in labor although its use has elicited promising results (Jones, Othman, Dowswell, et al., 2012; Smith, Collins, Cyna, et al., 2006; Zwelling, Johnson, and Allen, 2006). Music, recorded or live, can provide a distraction, enhance relaxation, and lift spirits during labor, thereby reducing the woman’s level of stress, anxiety, and perception of pain. It can be used to promote relaxation in early labor and to stimulate movement as labor progresses. Music can help create a more relaxed atmosphere in the birth room, leading to a more relaxed approach by health care providers (Creehan, 2008; Zwelling, Johnson, and Allen, 2006). Women should be encouraged to prepare their musical preferences in advance and to bring a CD player or MP3 player (e.g., iPod) to the hospital or birthing center. They should choose familiar music that is associated with pleasant memories, which can also facilitate the process of guided imagery. Use of a headset or earphones may increase the effectiveness of the music because other sounds will be shut out. Live music provided at the bedside by a support person may be very helpful in transmitting energy that decreases tension and elevates mood. Changing the tempo of the music to coincide with the rate and rhythm of each breathing technique may facilitate proper pacing. Evidence is insufficient to support the effectiveness of music as a method of pain relief during labor. Further research is recommended (Smith, Collins, Cyna, et al., 2006).

Pain Management

Pain During Labor and Birth

Neurologic Origins

Perception of Pain

Factors Influencing Pain Response

Physiologic Factors

Culture

Anxiety

Previous Experience

Comfort

Support

Environment

Nonpharmacologic Pain Management

Relaxation and Breathing Techniques

Relaxation

Breathing Techniques

Effleurage and Counterpressure

Touch and Massage

Application of Heat and Cold

Acupressure and Acupuncture

Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation

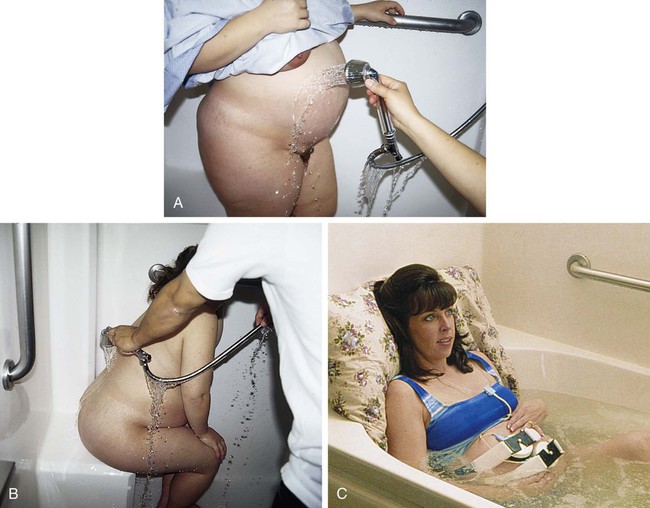

Water Therapy (Hydrotherapy)

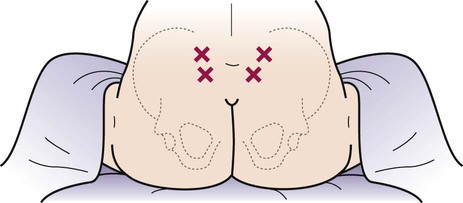

Intradermal Water Block

Aromatherapy

Music

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access