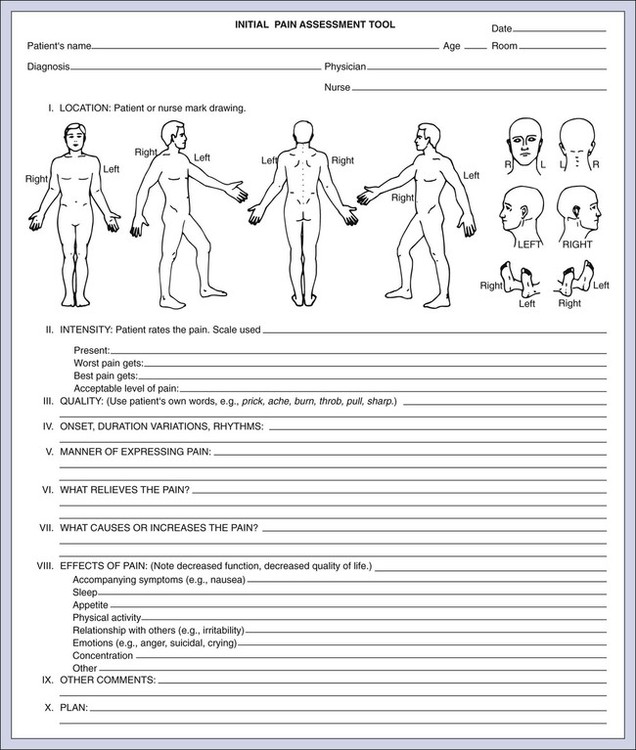

On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Define the concept of pain. 2. Identify factors that affect the elder’s pain experience. 3. Identify barriers that interfere with pain assessment and treatment. 4. Describe data to include in a pain assessment. 5. Discuss pharmacological and non-pharmacological pain management therapies. The International Association for the Study of Pain defines pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage . . . always subjective . . . a sensation . . . always unpleasant” (International Association for the Study of Pain, 2010). Physical pain can be a fleeting discomfort or something so pervasive that it wears heavily on one’s spirit. In young adulthood, pain is frequently the result of an acute event. The cause is clear (e.g., a fracture or infection), and treatment is based on intensity of the pain, which resolves when the underlying cause is treated. While those at midlife and beyond continue to experience acute events, the pain experience itself becomes more complex; acute pain occurs in the presence of co-morbidities including chronic, that is, persistent pain. The pain is more likely to be multidimensional with sensory, physical, psychosocial, emotional, and spiritual components. How we respond to pain is a part of who we are—part of our personalities (Box 17-1). Even the words used to describe it are many, an ache, a burn, a pester—with the language and the willingness to express it a manifestation of the person’s culture and relationship with whom he or she is speaking to (Campbell, Andrews, Scipio et al., 2009). In 2001, The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, made pain management a patient right, referring to it as the fifth vital sign (Joint Commission, 2009; Schofield, 2010). It became the expectation that health care professionals recognize and treat pain effectively and efficiently and, in doing so, provide comfort and caring. Additionally, in the nursing home setting, pain is one of the quality indicators, and the nurse is required to determine the presence or absence of pain when completing the Minimum Data Set (MDS 3.0) assessment. Knowing skills were needed to meet this basic standard of human caring, the American Nurses Association, in collaboration with the American Society of Pain Management Nursing, developed Pain Management Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice, and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC) offers a certification examination on pain management for nurses at the generalist level. Yet research continues to tell us that pain in the older adult is undertreated, especially those with cognitive impairments and most especially elders of color (Arnstein, 2010; Herr, 2010; Papaleontiou et al., 2010). Pain is usually first classified as cancer or non-cancer related. It is either acute or persistent, and, finally, it is nociceptive, neuropathic, or idiopathic (Box 17-2). Acute pain is temporary and usually controllable with adequate dosages of analgesia. For example, the acute pain of a myocardial infarction is relieved temporarily with morphine and permanently when oxygen is restored to the myocardium. Everyone experiences acute physical pain at some point in their lives. The most common type of pain in late life is chronic (i.e., persistent), and while the intensity may vary from day to day or hour to hour it is present most of the time (if not always) in the older adult. It is most likely felt in more than one location at a time, such as in both knees or both hands. Persistent pain is multifactorial in nature and can manifest as depression, eating and sleeping disturbances, impaired function, and confusion (Jansen, 2008). If left untreated, the effects are broad ranging, regardless of the cognitive capacity of the person in pain (Box 17-3). Research has found that pain in late life tends to be persistent, moderate to severe, and present in about 50% of those over 65 living in the community in the United States (Schofield, 2010). For those living in long-term care settings, the number of persons with pain, largely untreated, is thought to be much higher (Robinson, 2010). The barriers to adequate pain management in older adults are many (Boxes 17-4 and 17-5). The most common causes of non-cancer pain in late life are musculoskeletal in nature, especially from arthritis and degenerative spinal conditions, with neuralgias common as well (American Geriatrics Society [AGS], 2009). Neuralgias occur frequently as a result of long-standing diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, herpes zoster, and other syndromes (Box 17-6). In later life, acute pain may be superimposed on persistent pain and in an effort to treat either, we add an iatrogenic source for new pain. An example follows: Persons with cognitive impairment are consistently untreated or undertreated for pain. Studies have shown that older adults who are cognitively impaired receive less pain medication, even though they experience the same painful conditions as elders who are cognitively intact (Herr and Decker, 2004; Herr et al., 2006a,b; Kovach et al., 2006a,b; Ware et al., 2006). Many caregivers believe that people who are cognitively impaired do not experience pain as severely as those who are cognitively intact. However, according to Herr and Decker (2004, pp. 47-48): As a result, responses to painful experiences may be different from the “typical” response of a person who is cognitively intact. It is best to practice under the “assumption that any condition that is painful to a cognitively intact person would also be painful to those with advanced dementia who cannot express themselves” (Herr et al., 2010). Research has suggested that older people with mild to moderate cognitive impairment can provide valid reports of pain using self-report scales, but people with more severe impairment and loss of language skills may be unable to communicate the presence of pain in a manner that is easily understood but should be treated nonetheless (Herr & Decker, 2004; Herr et al., 2006a; Kovach et al., 2006a; Ware et al., 2006). For those with dementia who are no longer able to express themselves verbally, communication of pain usually occurs through changes in behavior, such as agitation, aggression, increased confusion, or passivity. Caregivers should be educated to be particularly alert for passive behaviors because they are less disruptive and may not be recognized as changes that may signal pain. Providing comfort to those who cannot express themselves requires careful observation of behavior and attention to caregiver reports, knowing when subtle changes have occurred, and a willingness to help (Box 17-7). In nursing homes, the certified nursing assistants play an important role in pain assessment. Regular assessment, use of standardized tools with consistent documentation, and communication are the most important components of pain assessment (Figure 17-1). This leads to the ability to adjust the plan of care promptly, consistently, and expertly in the promotion of comfort. Considering pain as the fifth vital sign is not a consideration of simply the presence or absence of pain, but the self-rating of intensity. Assessment always begins with a patient’s self-report of pain and usually includes uses a Likert-type rating or Visual analog of some type . A comprehensive pain assessment includes the identification of the factors influencing the pain experience and the opportunity for comfort (Box 17-8). This is the subjective and the objective whole of what it means to have pain, be a person in pain and one who finds relief. It includes what has hurt in the past and what has helped and how the pain affects function and role (Box 17-9). Awareness of the individual’s health wellness paradigm is especially important in a pain assessment (see Chapter 5). What does the pain mean? Is the pain believed to be the result of imbalance, a form of punishment, or an infection? A good pain assessment includes a determination of the cause for this pain if possible, and what has been done and can be done to treat the cause if possible. Detailed assessment pain protocols and videos are available through the Hartford Geriatric Nursing Institute at http://consultgerirn.org/topics/pain/want_to_know_more. The pain assessment takes on more meaning if it is conducted during activity, such as during physical therapy or in day-to-day nursing activities. Travis and colleagues (2003) use the term iatrogenic disturbance pain (IDP) to describe a type of pain that can be caused by the care provider. The authors suggest that, in some circumstances, tasks such as application of a blood pressure cuff, transfers out of bed, bathing, and moving and repositioning patients in the bed may cause an unacceptable level of discomfort. Patients with severe physical limitations (e.g., contractures) and significant cognitive impairment and persons at the end of life may be particularly likely to experience IDP. Travis and colleagues (2003) suggest the use of a 5-day IDP tracking sheet for assessment and monitoring of IDP. Other suggestions provided include gentle handling, adequate staffing, appropriate lifting devices and techniques, analgesic administration before care or treatments that may cause discomfort, education of staff on proper lifting and moving techniques, and assessment of discomfort during care provision.

Pain and Comfort

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/TwdHlthAging

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/TwdHlthAging

Pain In The Older Adult

Pain in Elders with Cognitive Impairments

Non-Verbal Expressions of Pain

Promoting Healthy Aging: Implications for Gerontological Nursing

Assessment

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Pain and Comfort

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access