On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Discuss touch and intimacy as integral components of sexuality. 2. Discuss the therapeutic benefits of touch for older people. 3. Discuss the physiological, social, and psychological factors that affect the older adult’s sexual function. 4. Describe the various approaches to sexuality assessment that may reduce nurse-client anxiety in discussing a sensitive area. 5. Identify the risks to sexual integrity. 6. Discuss interventions that foster sexual integrity. 7. Develop a plan of care for an elder to promote sexual health. Touch is the first of our senses to develop and provides us with our most fundamental means of contact with the external world (Gallace and Spence, 2010). It is the oldest, most important, and most neglected of our senses. Touch is 10 times stronger than verbal or emotional contact. All other senses have an organ on which to focus, but touch is everywhere. Touch is unique because it frequently combines with other senses. An individual can survive without one or more of the other senses, but no one can survive and live in any degree of comfort without touch. In the absence of touching or being touched, people of all ages can become sick and become touch starved. “Touch is experienced physically as a sensation as well as affectively as emotion and behavior. The interaction of touch affects the autonomic, reticular, and limbic systems, and thus profoundly affects the emotional drives” (Kim and Buschmann, 2004, p. 35). The Touch model proposed by Hollinger and Buschmann (1993) proposes that attitudes toward touch and acceptance of touch affect the behaviors of both caregivers and patients. Two types of touch occur during the nurse-patient relationship: procedural and non-procedural. Procedural touch (task-oriented or instrumental touch) is physical contact that occurs when a particular task is being performed. Non-procedural touch (expressive physical touch) does not require a task but is affective and supportive in nature, such as holding a patient’s hand. Nurses should recognize the influence of their own personality, cultural expectations, and early exposure to touching. Everyone has definite feelings and opinions about touch based on his or her own life experience. “Individuals learn the boundaries of tactual communication culturally” (Kim and Buschmann, 2004, p. 37). Touch only if it is comfortable, and do not assume that a person likes or wants to be touched (Rheaume and Mitty, 2008). Individuals quickly discern the discomfort of another if touch is not an integral part of behavior. It is important to remember that the comfort of touching depends on the location of touch, the situation, social status, culture, and age. Hall (1969) identifies different categories of touching—expanding or contracting zones around which every individual extends the sensory experience of touching, smelling, hearing, and seeing. The categories of touching include the intimate, vulnerable, consent, and social zone (Figure 21-1). Entering the zone of intimacy, which is identified as being in an area within an arm’s length of the individual’s body and is the space used for comforting, protecting, and lovemaking, is part of the nurse’s function. The vulnerable zone is highly sexually charged and will be protected. The most intimate area, the genitalia, is the most personally protected area of the body and causes the most stress and anxiety when approached, touched, or viewed by the caregiver. The consent zone requires the nurse to seek out or ask permission to touch or initiate procedures to these areas. The social zone includes the areas of the body that are the least sensitive or embarrassing to be touched and that do not necessarily require permission to be handled. Montagu (1986) noted that “tactile hunger” becomes more powerful in old age when other sensuous experiences are diminished and direct sexual expression is often no longer possible or available. Furthermore, Montagu believes the cause of illness may be greatly influenced by the quality of tactile support received. Do older people suffer touch deprivation? Many elders do if they are separated from caring others. Older men, in particular, may find it hard to reach out to others for comforting and caring touch. The previous lifestyles of these men often discouraged touch, except in the intimacy of sexual contact, which may no longer be available to them (Montagu, 1986). Older women are allowed considerably more freedom to touch, although they may lack the opportunity. Studies have shown that older women have reduced access to nonsexual intimacy, such as greeting someone with a hug or kiss or playing or cuddling with a grandchild (Waite et al., 2009). Since older women are more often widowed, reduced access to these other forms of nonsexual intimacy can further deprive them of warm and loving contact. In the cases of the isolated or institutionalized older person, higher death rates are more related to the quality of human relationships than they are to the degree of cleanliness, nutrition, and physical disabilities on which we focus. Sansone and Schmitt (2000) noted that older people in nursing homes experience touch every day as they are bathed, dressed, toileted, fed, and positioned. The type of touch they desire is not task-oriented touch but “gentle, patient, conscious touch of another person that says to them, ‘I’m here, I care, you are important to me.’ It’s the kind of touch that goes beyond routine and bonds one human being with another” (p. 304). People can survive extreme sensory deprivation as long as the sensory experiences of the skin are maintained. An outstanding feature of touch according to Ackerman (1995) is that it does not have to be performed by a person or other living thing. Some sustenance or peace for the old may be gained from the self-contained stimulation of a rocking chair or slowly stroking an animal’s fur or wearing something that provides sensory stimulation. Music, perceived through the skin as well as the ears, may be another source of touch stimulation that is self-induced. Skin touched by the vibrations of music is enveloped and caressed. Music and dancing seem to be two important mechanisms of enjoyment of older people (Chapter 24). In later years, older adults often return to dancing after decades of ignoring the pleasurable activity. Perhaps this desire is a response to the need for more touch. Kreiger’s experiments with therapeutic touch (1975) demonstrate physiological and psychological improvement in patients who are exposed to consistent “doses” of touch. “Hands-on healing and energy based interventions have been found in cultures throughout history, dating back at least 5000 years” (Wang and Hermann, 2006, p. 34). “Laying on of the hands” and the power of touch to heal had largely disappeared with the scientific revolution. The phenomenon has reemerged as healing touch and therapeutic touch movements. A growing body of research supports the healing power of touch, and Energy Field, Disturbed is an approved nursing diagnosis (Wang and Hermann, 2006, p. 34). Many nurses have learned how to perform therapeutic and healing touch and use these modalities in their practice with people of all ages. Positive outcomes of interventions utilizing touch in nursing homes, particularly with people with dementia and agitated behaviors, have been reported (Box 21-1). Further research on the use of touch with older people is needed. Touch is a powerful tool to promote comfort and well-being when working with elders. Although intimacy is often thought of in the context of sexual performance, it encompasses more than sexuality and includes five major relational components: commitment, affective intimacy, cognitive intimacy, physical intimacy, and interdependence (Youngkin, 2004). “Intimacy is from a Greek work meaning ‘closest to; inner lining of blood vessels’ ” (Steinke, 2005, p. 40). It is a warm, meaningful feeling of joy. Intimacy includes the need for close friendships; relationships with family, friends, and formal caregivers; spiritual connections; knowing that one matters in someone else’s life; and the ability to form satisfying social relationships with others (Steinke, 2005). Youngkin (2004) points out that older people may be concerned about changes in sexual intimacy but “social relationships with people important in their lives, the ability to interact intellectually with people who share similar interests, the supportive love that grows between human beings (whether romantic or platonic), and physical nonsexual intimacy are equally—and in many instances more—important than the physical intimacy of direct sexual relations. All of these facets of intimate life are integrally woven into the fabric of aging, along with other influences that can make life rewarding” (p. 46). Intimacy needs change over time, but the need for intimacy and satisfying social relationships remains an important component of healthy aging. Sexuality is defined as a central aspect of being human and encompasses sex, gender identities and roles, sexual orientation, eroticism, pleasure, intimacy, and reproduction (World Health Organization, 2004). As a major aspect of intimacy, sexuality includes the physical act of intercourse, as well as many other types of intimate activity. It includes components such as sexual desire, activity, attitudes, body image, and gender-role activity (Zeiss and Kasl-Godley, 2001). Sexuality provides the opportunity to express passion, affection, admiration, and loyalty. It can also enhance personal growth and communication. Sexuality also allows a general affirmation of life (especially joy) and a continuing opportunity to search for new growth and experience. Sexuality, similar to food and water, is a basic human need, yet it goes beyond the biological realm to include psychological, social, and moral dimensions (Waite et al., 2009) (Figure 21-2). The constant interaction among these spheres of sexuality work to produce harmony. The linkage of the four dimensions composes the holistic quality of an individual’s sexuality. The social sphere of sexuality is the sum of cultural factors that influence the individual’s thoughts and actions related to interpersonal relationships, as well as sexuality related to ideas and learned behavior. Television, radio, literature, and the more traditional sources of family, school, and religious teachings combine to influence social sexuality. The belief of that which constitutes masculine and feminine is deeply rooted in the individual’s exposure to cultural factors (Chapter 5). Sexuality validates the lifelong need to share intimacy and have that offering appreciated. Sexuality is love, warmth, sharing, and touching between people, not just the physical act of coitus. Margot Benary-Isbert, in her book The Vintage Years (1968), expresses the essence of sexuality most eloquently (p. 200): Man believed that repressing his feminine traits was virtuous; and woman, until recently, repressed her animus. Both men and women, however, are not consciously aware that they possess the opposite sexual identity. Goldblatt (1972) contends that neither gonads nor chromosomal sex is a determinant of sexual behavior. Money and Tucker (1975), in their work Sexual Signatures, believe that social stimulation provides gender identity and limits the individual’s concept of self. In essence, society expects men to be men and women to be women. In the latter part of life, self-knowledge deepens. People tend to discover traits in their nature that were previously suppressed or heretofore remained in the unconscious. At this time, the emergence of the anima (in men) and animus (in women) may be seen. Jung identified this experience as the expression of the psyche that in the first half of life was turned inward. In late life, directed outward, this expression becomes indicative of the capacity for fuller living. Men become more comfortable with tenderness, “more dependent on the marriage for their sense of well-being, and more willing to accommodate for the sake of preserving peace” (Huyck, 2001, p. 11). Women become more assertive and self-confident. The person’s ability to accord his or her other nature its due recognition will enhance sexuality. The World Health Organization defines sexual health as a state of physical, emotional, mental, and social well-being related to sexuality (2004). Sexual health is a realistic phenomenon that includes four components: personal and social behaviors in agreement with individual gender identity; comfort with a range of sexual role behaviors and engagement in effective interpersonal relations with both sexes in a loving relationship or long-term commitment; response to erotic stimulation that produces positive and pleasurable sexual activity; and the ability to make mature judgments about sexual behavior congruent with one’s beliefs and values. “Sexual health, as with physical health, is not simply the absence of sexual dysfunction or disease, but, rather a state of sexual well-being that includes a positive approach to a sexual relationship and anticipation of a pleasurable experience without fear, shame, or coercion” (Rheaume and Mitty, 2008, p. 342). A large number of cultural, biological, psychosocial, and environmental factors influence the sexual behavior of older adults. The older person may be confronted with barriers to the expression of his or her sexuality by reflected attitudes, health, culture, economics, opportunity, and historic trends. Factors affecting a person’s attitudes on intimacy and sexuality include family dynamics and upbringing and cultural and religious beliefs (Chapter 5). Older people often internalize the broad cultural proscriptions of sexual behavior in late life that hinder the continuance of sexual expression. Much sexual behavior stems from incorporating other people’s reactions. Older people do not feel old until they are faced with the fact that others around them consider them old. Similarly, older adults do not feel asexual until they are continually treated as such. American society continues to struggle with open acceptance of sexual expression for the young but continues to remain hostile to the attempts of older people to do the same. Sexual interest and activity in older adults are sometimes regarded as deviant behavior and described in such terms as “dirty old man,” “lecher,” and “old biddy.” The same activity attempted by a younger person would be viewed as appropriate. An often quoted statement by Alex Comfort (1974) sums it up nicely: “In our experiences, old folks stop having sex for the same reasons they stop riding a bicycle—general infirmity, thinking it looks ridiculous, no bicycle.” Box 21-2 presents some of the myths about sexuality in older people that may be held by older people themselves and by society in general. For both heterosexual and homosexual individuals, research supports that liberal and positive attitudes toward sexuality, greater sexual knowledge, satisfaction with a long-term relationship or a current intimate relationship, good social networks, psychological well-being, and a sense of self-worth are associated with greater sexual interest, activity, and satisfaction. Both early studies of sexual behavior in older adults, and more recent ones, indicate that men and women remain sexually active and find their sexual lives satisfying. Determinants of sexual activity and functioning include the interaction of each partner’s sexual capacity, motivation, conduct, and attitudes, as well as the quality of the dyadic relationship (Waite et al., 2009). Patterns of sexual activity in earlier years are the major predictor of sexual activity in later life, and individuals with higher levels of sexual activity in middle age show less decline with advanced age (Kennedy et al., 2010). The National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP) is a national probability survey of 3005 men and women between ages 57 and 85 that is focused on intimate social relationships, including marriage, social ties, and sexuality. The central hypothesis of the study is that individuals with high-quality intimate social and sexual relationships will age better in terms of health and well-being than those with poor-quality relationships or those who lack social relationships (Lindau et al., 2007; Lindau and Gavrilova, 2010; Suzman, 2009). Findings from this survey revealed that about three quarters of individuals ages 57 to 85 are married or living with a partner and three quarters of those are sexually active. The prevalence of sexual activity declined with age: 73% of people between ages 57 and 64 reported being sexually active; 53% of those between ages 65 and 74; and 26% of those between ages 75 and 85. Sexual activity was closely tied to overall health, and people whose health was rated as excellent or very good were nearly twice as likely to be sexually active as those who rated their health as poorer. The most common reason for sexual inactivity among those with a partner was the male partner’s health. Men are more sexually active than women, most likely because women live longer and may not have a partner. Women, especially those not in a relationship, were more likely than men to report lack of interest in sex (Lindau et al., 2007; Lindau and Gavrilova, 2010). The era in which a person was born influences attitudes about sexuality. Women in their 80s today may have been strongly influenced by the prudish, Victorian atmosphere of their youth and may have experienced difficult marital adjustments and serious sexual problems early in their marriages. Sexuality was not openly expressed or discussed, and this was a time when “pleasurable sex was for men only; women engaged in sexual activity to satisfy their husbands and to make babies” (Rheaume and Mitty, 2008, p. 344). These kinds of experiences shape beliefs and knowledge about sexual expression as well as comfort with sexuality, particularly for older women. It is important to come to know and understand the older person within his or her social and cultural background and not make judgments based on one’s own belief system. Most of what is known about sexuality in aging has been gained through research with well-educated, healthy, white older adults. Further research is needed among culturally, socially, and ethnically diverse older people; those with chronic illness; and gay, lesbian, and bisexual older people. Suzman (2009) suggests the importance of early life experiences in understanding aging and sexual patterns, an area missing when studies focus on experiences after age 65 only. Acknowledgement and understanding of the age changes that influence sexual physiology, anatomy, and the stages of sexual response may partially explain alteration in sexual behavior to accommodate these changes and facilitate continued pleasurable sex. Characteristic physiological changes during the sexual response cycle do occur with aging, but these vary from individual to individual depending on general health factors. The changes occur abruptly in women starting with menopause but more gradually in men, a phenomenon called andropause (Kennedy et al., 2010). The “use it or lose it” phenomenon also applies here: the more sexually active the person is, the fewer changes he or she is likely to experience in the pattern of sexual response. Changes in the appearance of the body (wrinkles, sagging skin) may also affect the older person’s security about his or her sexual attractiveness (Arena and Wallace, 2008). Table 21-1 summarizes physical changes in the sexual response cycle. TABLE 21-1 PHYSICAL CHANGES IN SEXUAL RESPONSES IN OLD AGE

Intimacy and Sexuality

Touch

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/TwdHlthAging

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/TwdHlthAging

Response to Touch

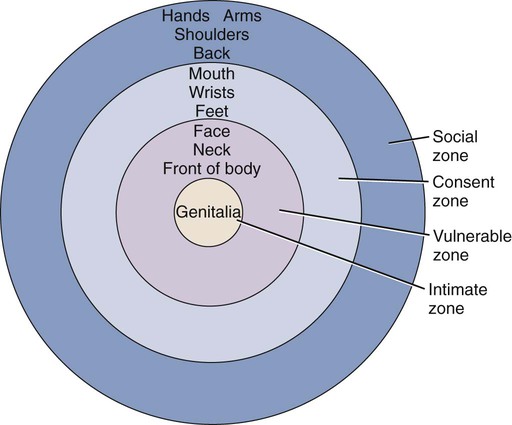

Touch Zones

Touch Deprivation

Adaptation to Touch Deprivation

Therapeutic Touch

Intimacy

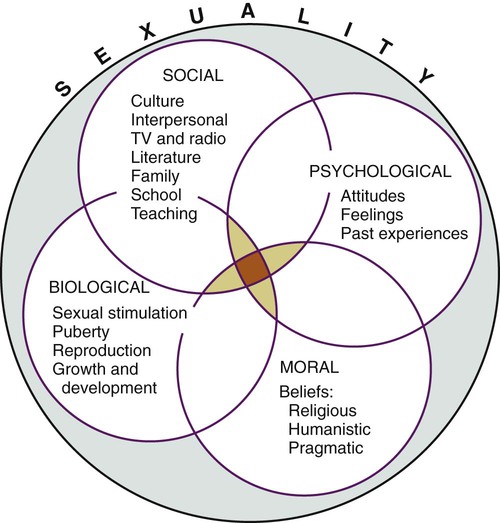

Sexuality

Acceptance and Companionship

Femininity and Masculinity

Sexual Health

Factors Influencing Sexual Health

Expectations

Activity Levels

Cohort and Cultural Influences

Biological Changes with Age

FEMALE

MALE

Excitation Phase

Diminished or delayed lubrication (one to three minutes may be required for adequate amounts to appear)

Less intense and slower erection (but can be maintained longer without ejaculation)

Diminished flattening and separation of labia majora

Increased difficulty regaining an erection if lost

Disappearance of elevation of labia majora

Less vasocongestion of scrotal sac

Decreased vasocongestion of labia minora

Less pronounced elevation and congestion of testicles

Decreased elastic expansion of vagina (depth and breadth)

Breasts not as engorged

Sex flush absent

Plateau Phase

Slower and less prominent uterine elevation or tenting

Decreased muscle tension

Nipple erection and sexual flush less often

No color change at coronal edge of penis

Decreased capacity for vasocongestion

Slower penile erection pattern

Decreased areolar engorgement

Delayed or diminished erectal and testicular elevation

Labial color change less evident

Less intense swelling or orgasmic platform

Less sexual flush

Decreased secretions of Bartholin glands

Orgasmic Phase

Fewer number and less intense orgasmic contractions

Decreased or absent secretory activity (lubrication) by Cowper gland before ejaculation

Rectal sphincter contraction with severe tension only

Fewer penile contractions

Fewer rectal sphincter contractions

Decreased force of ejaculation (approximately 50%) with decreased amount of semen (if ejaculation is long, seepage of semen occurs)

Resolution Phase

Observably slower loss of nipple erection

Vasocongestion of nipples and scrotum slowly subsides

Vasocongestion of clitoris and orgasmic platform

Very rapid loss of erection and descent of testicles shortly after ejaculation

Refractory time extended (time required before another erection ranges from several to 24 hours, occasionally longer) ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree