On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Identify interactions of intrapersonal, interpersonal, geographical, economic, and health factors that influence environmental safety and security for older adults. 2. Discuss the effects of declining health, reduced mobility, isolation, and unpredictable life situations on the older adult’s perception of security. 3. Explain the underlying vulnerability of older adults to effects of extreme temperatures, and identify actions to prevent and treat hypothermia and hyperthermia. 4. Define strategies and programs designed to prevent, detect, or alleviate crimes against older adults. 5. Consider the impact of available transportation and driving in relation to independence. 6. Discuss the use of assistive technologies to promote self-care, safety, and independence. Home safety assessments must be multifaceted and individualized to the areas of identified risks. They are particularly important for the older adult with fall risk and are recommended in evidence-based protocols for fall-risk reduction. An evidence-based home safety assessment tool, developed by Tanner (2003), includes fall and injury risk, as well as fire and crime risk assessment (Table 13-1). Home safety assessments targeted at fall-risk reduction are available from www.cdc.gov.injury in formats easy for older adults to access and use. Hurley and colleagues (2004) describe a home safety injury model for persons with Alzheimer’s disease and their caregivers that addresses the physical environment and caregiver competence. Special home modifications for persons with Alzheimer’s disease have also been described (Warner, 2000). Chapter 19 discusses safety and dementia as well. TABLE 13-1 ASSESSMENT AND INTERVENTIONS OF THE HOME ENVIRONMENT FOR OLDER PERSONS Modified from Rehabilitation Engineering Research Center on Aging (RERC-Aging), Center for Assistive Technology, University at Buffalo. To be vigilant or aware of older adults at risk, it is important to understand the basis of thermal vulnerability. Neurosensory changes in thermoregulation delay or diminish the older person’s awareness of temperature changes and may impair behavioral and thermoregulatory response to dangerously high or low environmental temperatures (Chapter 4). Decline in thermoregulatory responsiveness to temperature extremes as one ages is well documented, yet these changes vary widely among individuals and are related more to general health than to age. The delicate equilibrium required to maintain thermal balance at any age involves the generation or replacement of body heat at about the same rate as heat is lost to the environment. Diminished thermoregulatory responses and abnormalities in both the production and response to endogenous pyrogens may contribute to differences in fever responses between older and younger patients in response to an infection. Up to one-third of older people with acute infections may present without a robust febrile response, leading to delays in diagnosis and appropriate treatment, as well as increased morbidity and mortality (Outzen, 2009). Careful attention to temperature monitoring in older adults is very important, and often this technical task is not given adequate attention by professional nurses. Frail older adults have lower baseline temperatures than healthy younger persons. In one study, the mean oral baseline temperature of randomly selected nursing home residents was 36.3° C (97.34° F). Therefore, a temperature of 98.34° F can represent one degree of elevation and may be significant in indicating infection. It is important to remember that acute infection in older adults frequently presents with a change in functional status, regardless of whether or not there is a temperature elevation. Fever in older adults can be defined as a persistent oral or TM temperature ≥37.2° C (98.96° F) or a persistent rectal temperature ≥37.5° C (99.5° F). Temperatures reaching or exceeding 38.3° C (100.94° F) are very serious in older people and are more likely to be associated with serious bacterial or viral infections (Norman, 2000). More older people die from excessive heat than from hurricanes, lightening, tornadoes, floods, and earthquakes combined (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006). When body temperature increases above normal ranges because of environmental or metabolic heat loads, a clinical condition called heat illness, or hyperthermia, develops. Heat illnesses tend to follow a continuum (Table 13-2), beginning with mild heat fatigue and ending with the potentially fatal heat stroke, so it is imperative to assess hyperthermia quickly and appropriately. Heat fatigue is usually caused by exposure to high outside temperatures or overexertion in a hot environment. It is characterized by pale or sweaty skin that is still moist and cool to touch, elevated heart rate, and feelings of exhaustion and weakness. Core body temperature remains normal (Ham et al., 2007). Diuretics and low intake of fluids exacerbate fluid loss and can precipitate the onset of hyperthermia in hot weather. TABLE 13-2 Modified from: Ham R, et al: Primary care geriatrics: A case-based approach, ed 5, St. Louis, 2007, Mosby; Ebersole P, et al: Toward Healthy Aging: Human needs and nursing response, ed 7, St. Louis, 2008, Mosby. Box 13-1 presents interventions to prevent hyperthermia when the ambient temperature exceeds 90° F (32.2° C). Local governments and communities must coordinate response strategies to protect the older person when environmental temperatures rise. Strategies may include providing fans, opportunities to spend part of the day in air-conditioned buildings, and identification of high-risk older people. Nearly 50% of all deaths from hypothermia occur in older adults (Ham et al., 2007). Hypothermia is produced by exposure to cold environmental temperatures and is defined as a core temperature of less than 35° C (95° F). Hypothermia is categorized into mild, moderate, and severe, depending on the core temperature taken with a rectal probe thermometer. Hypothermia is a medical emergency requiring comprehensive assessment of neurological activity, oxygenation, renal function, and fluid and electrolyte balance. Unfortunately, a dulling of awareness accompanies hypothermia, and persons experiencing the condition rarely recognize the problem or seek assistance. For the very old and frail, environmental temperatures below 65° F (18° C) may cause a serious drop in core body temperature to 95° F (35° C). Factors that increase the risk of hypothermia are numerous, as shown in Box 13-2. Under normal temperature conditions, heat is produced in sufficient quantities by cellular metabolism of food, friction produced by contracting muscles, and the flow of blood. Paralyzed or immobile persons lack the ability to generate significant heat by muscle activity and become cold even in normal room temperatures. Persons who are emaciated and have poor nutrition lack insulation, as well as fuel for metabolic heat-generating processes, so they may be chronically mildly hypothermic. Box 13-3 lists factors that may induce low basal body temperatures in elders. All body systems are affected by hypothermia, although the most deadly consequences involve cardiac arrhythmias and suppression of respiratory function. Correctly conducted rewarming is the key to good management, and the guiding principle is to warm the core before the periphery and raise the core temperature 0.5° C to 2° C per hour. Heating blankets and specially designed heating vests are used in addition to warm humidified air by mask, warm IV boluses, and other measures depending on the severity of the hypothermia (Ham et al., 2007). Detecting hypothermia among community-dwelling older adults is sometimes difficult, because unlike in the clinical setting, no one is measuring body temperature. For persons exposed to low temperatures in the home or the environment, confusion and disorientation may be the first overt signs. As judgment becomes clouded, a person may remove clothing or fail to seek shelter, and hypothermia can progress to profound levels. For this reason, regular contact with home-dwelling elders during cold weather is crucial. For those with preexisting alterations in thermoregulatory ability, this surveillance should include even mildly cool weather. Because heating costs are high in the United States, the Department of Health and Human Services provides funds to help low-income families pay their heating bills. Specific interventions to prevent hypothermia are shown in Box 13-4. Additional resources can be found on the Evolve website.

Environmental Safety and Security

Influences of Changing Health and Disability on Safety and Security

Physical Vulnerability

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/TwdHlthAging

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/TwdHlthAging

Home Safety

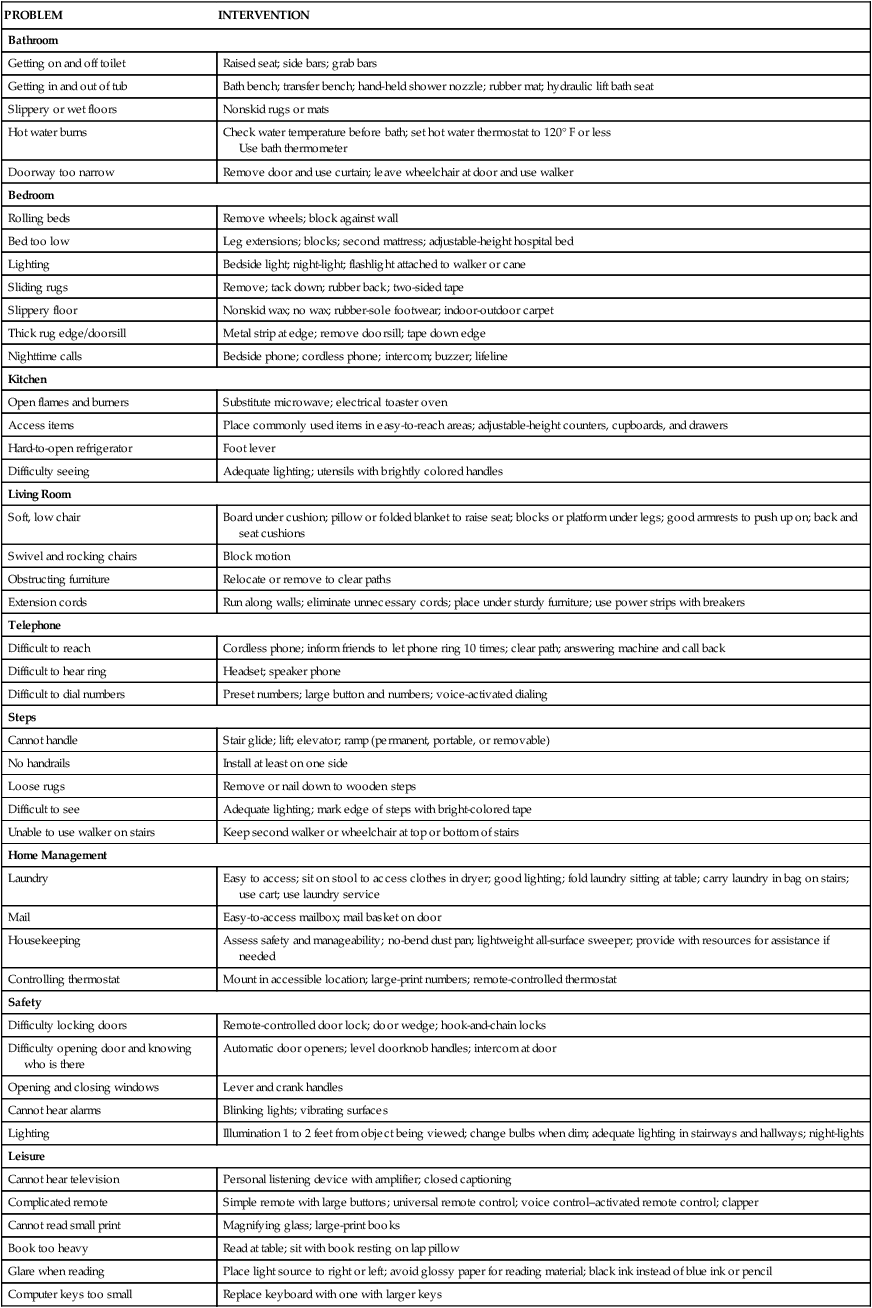

PROBLEM

INTERVENTION

Bathroom

Getting on and off toilet

Raised seat; side bars; grab bars

Getting in and out of tub

Bath bench; transfer bench; hand-held shower nozzle; rubber mat; hydraulic lift bath seat

Slippery or wet floors

Nonskid rugs or mats

Hot water burns

Check water temperature before bath; set hot water thermostat to 120° F or less

Use bath thermometer

Doorway too narrow

Remove door and use curtain; leave wheelchair at door and use walker

Bedroom

Rolling beds

Remove wheels; block against wall

Bed too low

Leg extensions; blocks; second mattress; adjustable-height hospital bed

Lighting

Bedside light; night-light; flashlight attached to walker or cane

Sliding rugs

Remove; tack down; rubber back; two-sided tape

Slippery floor

Nonskid wax; no wax; rubber-sole footwear; indoor-outdoor carpet

Thick rug edge/doorsill

Metal strip at edge; remove doorsill; tape down edge

Nighttime calls

Bedside phone; cordless phone; intercom; buzzer; lifeline

Kitchen

Open flames and burners

Substitute microwave; electrical toaster oven

Access items

Place commonly used items in easy-to-reach areas; adjustable-height counters, cupboards, and drawers

Hard-to-open refrigerator

Foot lever

Difficulty seeing

Adequate lighting; utensils with brightly colored handles

Living Room

Soft, low chair

Board under cushion; pillow or folded blanket to raise seat; blocks or platform under legs; good armrests to push up on; back and seat cushions

Swivel and rocking chairs

Block motion

Obstructing furniture

Relocate or remove to clear paths

Extension cords

Run along walls; eliminate unnecessary cords; place under sturdy furniture; use power strips with breakers

Telephone

Difficult to reach

Cordless phone; inform friends to let phone ring 10 times; clear path; answering machine and call back

Difficult to hear ring

Headset; speaker phone

Difficult to dial numbers

Preset numbers; large button and numbers; voice-activated dialing

Steps

Cannot handle

Stair glide; lift; elevator; ramp (permanent, portable, or removable)

No handrails

Install at least on one side

Loose rugs

Remove or nail down to wooden steps

Difficult to see

Adequate lighting; mark edge of steps with bright-colored tape

Unable to use walker on stairs

Keep second walker or wheelchair at top or bottom of stairs

Home Management

Laundry

Easy to access; sit on stool to access clothes in dryer; good lighting; fold laundry sitting at table; carry laundry in bag on stairs; use cart; use laundry service

Mail

Easy-to-access mailbox; mail basket on door

Housekeeping

Assess safety and manageability; no-bend dust pan; lightweight all-surface sweeper; provide with resources for assistance if needed

Controlling thermostat

Mount in accessible location; large-print numbers; remote-controlled thermostat

Safety

Difficulty locking doors

Remote-controlled door lock; door wedge; hook-and-chain locks

Difficulty opening door and knowing who is there

Automatic door openers; level doorknob handles; intercom at door

Opening and closing windows

Lever and crank handles

Cannot hear alarms

Blinking lights; vibrating surfaces

Lighting

Illumination 1 to 2 feet from object being viewed; change bulbs when dim; adequate lighting in stairways and hallways; night-lights

Leisure

Cannot hear television

Personal listening device with amplifier; closed captioning

Complicated remote

Simple remote with large buttons; universal remote control; voice control–activated remote control; clapper

Cannot read small print

Magnifying glass; large-print books

Book too heavy

Read at table; sit with book resting on lap pillow

Glare when reading

Place light source to right or left; avoid glossy paper for reading material; black ink instead of blue ink or pencil

Computer keys too small

Replace keyboard with one with larger keys

Vulnerability to Environmental Temperatures

Thermoregulation

Temperature Monitoring in Older Adults

Hyperthermia

ILLNESS

SYMPTOMS

TREATMENT

Heat fatigue/heat syncope

Pale, sweaty skin that is still cool and moist to the touch

Elevated heart rate and patient feels exhausted and weak

Body temperature remains normal

Some loss of vascular volume and electrolytes from sweating

Sudden syncopal spell or dizziness after exercising in the heat

Oral hydration with electrolyte replacement

Cooler, less humid environment

Rest

Heat cramps and heat exhaustion

Muscle cramping of legs, arms, or abdominal wall. Skin remains moist or cool and clammy, tachycardia, decreased pulse pressure, and thirst usually present. Altered mental status (giddy, confused, weak), nausea. Core temperature normal or mildly elevated.

Cool environment, hydration, IV normal saline, rest

Heat stroke

Mechanisms to control heat are lost, core temperature rises quickly (>104° F) and causes cellular and end organ damage, skin flushed and hot and dry. Mental status changes, tachycardia, hypotension, hyperventilation.

Complex medical emergency; if untreated will cause death. Cool person as rapidly as possible, IV infusions. Complications during treatment include hypoglycemia, shivering, seizures, renal failure, and hypotension.

Hypothermia

Environmental Safety and Security

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access