Margaret B. Harrison

- Implementation of evidence-based practice is typically complex, time consuming, and resource intensive and the importance of measuring outcomes is twofold: to evaluate the effectiveness of the change in practice and plan for its sustainability.

- Outcome concepts can usually be measured in various ways—the choice is a balance between scientific rigor and feasibility.

- Implementation teams need to take into account multiple perspectives with outcome selection considering individual/family, provider, and system-level measures.

Introduction

Implementation of evidence-based practice (EBP) is often complex, time consuming, and resource intensive. The importance of measuring outcomes is vital not only to evaluate the effectiveness of the change in practice, but also to invest in its sustainability. To accomplish this, implementation teams should consider evaluation and outcome selection from multiple perspectives. This chapter describes the types of outcome measures that can be used to evaluate implementation of EBP. Approaches to measurement, key outcome concepts, and selection of measurement methods will be presented, as well as the strengths and limitations of different approaches. The chapter describes a program of research focused on evidence-based implementation with chronic wound practices (pressure ulcers and leg ulcers) to illustrate the different purposes of these outcome measures, their effects on knowledge use by providers, and the impact on patients, providers, and the health system.

Background

During the mid-1990s the availability of quality practice guidelines provided a crucial impetus for the “best practice” movement. Settings and providers now had access to evidence in a useable form that could potentially be integrated into practice-based decision making to improve outcomes. The long-held notion of “that’s the way it has always been done” could and would be challenged. However, the reality of basing practice on best available evidence was far more difficult than any of us imagined.

Many nursing settings first actively experienced implementation of EBP to improve both the prevention and management of pressure ulcers. Pressure ulcers present a ubiquitous problem that cross sectors of care and patient populations and are, for the most part, deemed a nursing concern. Chronic leg ulcers provided another opportunity for implementation. Again, nurses deliver the majority of leg ulcer care to a population largely based in the community. With more than a dozen years beyond these early implementation initiatives in nursing, it has become increasingly clear how vital the evaluation, meticulous tailoring, and selection of outcomes in implementing EBP is to the whole process. The instrumental role that outcome measures can play will be illustrated using chronic wound cases as exemplars.

Members of our research team spanned a large Ontario health region in central Canada. The team first came together in the mid-1990s to implement practice guidelines for pressure ulcer prevention and management. Originally the effort was concentrated in acute care in one large teaching hospital but soon led to a diverse regional collaboration in different settings across the continuum of care. Around the same time, we undertook a second major initiative related to best practice with community-based leg ulcer care. With both examples a substantive research and quality component accompanied the guideline implementations. Much was learned about translating knowledge to practice, exposing the gap between having quality guidelines and actual implementation and the challenges with outcome measurement. Using these chronic wound cases I will highlight what worked in our efforts and what did not, and postulate the reasons why. The journey was rarely straightforward.

Building the case for change for EBP

Prevalence/incidence rates as outcome, the process as a monitoring mechanism

In both examples of pressure and leg ulcer EBP implementation, work began by determining the extent of the problem. The key questions facing us were, “How widespread were the problems/issues, and what were the profiles of the at-risk population”? Multiple sectors in our Eastern Ontario health-care region (population ~1 million) were engaged in a concerted effort to address issues related to pressure ulcer occurrence. Initial research to assess the extent of the problem and evaluate a risk assessment tool in a hospital setting provided the methodological foundation and practical tools to collect prevalence estimates (Fisher et al. 1996; Harrison et al. 1996). Because little occurrence information was available in administrative databases to understand the extent and severity of the problem, our group decided its first step must be the collection of primary data over time. This long-range study was, in turn, the basis of ongoing monitoring activity and the ongoing surveillance that resulted in yearly prevalence studies across the institution. “Prevalence” included a full head-to-toe skin assessment and risk profile using a recommended risk tool. The monitoring activity diffused into other settings and over time, and became a reliable, valid, and clinically feasible monitoring process. To participate in the prevalence data collection, surveyors were trained in comprehensive skin assessment and use of the risk tool. The education workshop included both theoretical and practical “hands-on” components in staging pressure ulcers. And, to evaluate our ability to collect this data, a validation team of two experienced surveyors reassessed a 10% reference sample of the prevalence population. The evaluation showed a strong relationship between the initial and reference sample assessments (Harrison et al. 1996).

The prevalence data collection provided the structure for a comprehensive local dataset from which to derive benchmarks and continue evaluating changes to care. For instance, the prevalence and incidence hospital data were analyzed and reported across the health-care setting, at the levels of hospital, program, and unit. Specific units with high chronic wound occurrences conducted more in-depth studies of their own patients and contextual factors with assistance from the nursing quality portfolio (Mackey et al. 2005). Over time the portfolio was used in different ways to drive the quality and continuing effort with EBP (Harrison 2008; Harrison et al. 1998). Quality monitoring processes emerged from the prevalence and incidence methodologies, providing the foundation from which care changes for improved pressure ulcer outcomes could be advocated. Incremental improvement could be tracked by specific ulcer stage indicating that although the overall prevalence may not have decreased, the severity of the problem had improved at a population level.

Like pressure ulcers, leg ulcers fall primarily under nursing purview. Again, little data was available from agency administrative databases. To gain an accurate picture of precisely how many individuals in the catchment area suffered from leg ulcers, and how many were potentially coming into care, it was again necessary to conduct prevalence, incidence, and profiling studies before implementation of recommendations from international guidelines could begin. Information was lacking about their numbers or their circumstances (age, mobility, progress of care). Because we were unable to find any Canadian epidemiology studies of this condition, we conducted a substantive review of international studies that documented rates and methodologies used to measure the problem (Graham et al. 2003a). To create a benchmark and produce this data for local decision makers and planners, we undertook a 1-month prospective study that included a full clinical assessment comprising an ankle-brachial pressure index, clinical history, socio-demographic and circumstance-of-living information. The attending nurse collected the information on a planned visit. This provided a composite of data of baseline statistics and benchmarks from which to assess future care and community management of this population (Graham et al. 2003a,b).

Understanding the environment and current care

Context and process of care, setting up process outcomes

Once the intended population to receive the evidence-informed care and services has been identified, the next task is typically to understand the context and provider practices. Environmental scans, provider knowledge, attitudes, practice (KAP) surveys, and process audits can all be useful approaches. Outcomes from these approaches include: the readiness of the environment and providers to implement changes, and the gap between current practice and best practice that must be addressed. In the case of pressure ulcers, an internal quality audit of patient charts revealed no consistent or standardized risk assessment for pressure ulcer risk. If a pressure ulcer was diagnosed, it was largely managed following a referral to the hospital-wide consultant, an enterostomal therapist. Yet the guidelines we followed at that time, the Agency of Health Care Policy and Research (1992) guideline recommendations, clearly advocated for identification of people at risk. To accomplish this, ongoing regular assessments must be conducted by regular, ongoing caregivers, that is, by bedside staff rather than consultants, to determine risk (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, AHCPR, 1992).

To assist us in meeting the many challenges raised by this implementation, we were guided by a research use framework to improve our ability to overcome barriers and make fruitful use of facilitating factors (Logan et al. 1999). The framework, the Ottawa Model of Research Use, helps us focus on important provider, environment, and guideline factors. For example, one barrier that became evident was nurses’ lack of knowledge and skill in using risk assessment tools. A training program was developed to assist nurses in the use of risk scales recommended in the guideline (AHCPR 1992). Guidelines provide a roadmap only. How the recommendations are enacted in a particular setting requires attention to the environmental details and articulation within a care protocol. When our audits indicated the need for a more visible outcome, a skin care task force was formed to review documentation and develop a mechanism to record assessment on the daily vital signs flow sheet within patients’ charts. This had the effect of improving documentation allowing for quality audits to track the number and timing of risk assessments, the proportion of patients “at risk,” how severe the risk was, and provided the potential to link this information to preventative interventions. Quality process outcomes (instrumental knowledge use or indicators) are important to providing a barometer of how well guideline recommendations are being adhered to in a setting.

In the case of community leg ulcer care, authority and decisionmaking capacity is held at both the individual provider and regional levels. A KAP survey of nurses and family physicians (Graham et al. 2001, 2003b) supplied a crucial impetus for the home-care authority to appreciate the willingness of providers to adhere to a regionally driven protocol. Once a referral was received for home-care services, a locally adapted evidence protocol outlined the plan of care (Graham et al. 2000); exceptions were made only by physician order. The KAP survey also brought to light existing gaps in provider skills and knowledge. Knowledge outcomes (conceptual knowledge use) for instance directed to the areas of evidence where physicians and nurses required more support. For example, additional effort was required to improve providers’ evidence-informed assessment capability. Nurses required training and equipment to carry this out. A key aspect of conducting a comprehensive clinical evaluation included performing an ankle-brachial pressure measurement index (ABPI) using handheld Dopplers. This was not standard equipment at the time for home-nursing agencies. Later these aspects (the availability of equipment, training incorporated in new staff nurse orientations) would be tracked as a process outcome in adhering to the guideline recommendations.

Another important outcome to come to light in the early stages of the leg ulcer best practice implementation project was system outcome such as resource use (Friedberg et al. 2002). This included administratively important outcomes such as nursing time, the number of visits, types and costs of supplies and equipment. In later evaluation efforts, these outcomes were influential for decision makers to make judgments about continuing with the newly organized service.

Measuring the impact of EBP/care

Evaluations and selecting practice and health services outcomes

Evaluations of implementation projects are an artful dance between rigor, timeliness, and feasibility. Planners and decision makers typically have a short window of opportunity to inform decisions, and evaluative data must be responsive to this reality. Often there is no time to wait for the perfect evaluation study. In the chronic wound examples presented in this chapter, implementations were evaluated from an integrated researcher, practitioner, and decision-maker perspective. For instance, the providers were largely interested in improving the wound to a point where day-to-day function was near normal. Decision makers were interested in reasonable periods of time on service and when improvement and coming off-service were feasible. From a research perspective, time-to-healing is considered a sensitive wound outcome. Thus given the chronic nature of leg ulcers, a 3-month healing rate was a reasonable compromise. Outcomes selection also needed to include system-level indicators of less interest to frontline providers. For instance, in both wound cases healing was an important clinical outcome, yet efficiencies and use of scarce resources (e.g., nursing time) were key for decision makers choosing between priorities. Needless to say, many challenges are faced at this stage of implementation both methodologically and practically.

Pressure ulcer outcomes were selected/derived from the original monitoring process using prevalence and incidence methodologies. Outcomes used in the hospital included: prevalence estimates, types and severity of risk based on 6 risk subscales (Bergstrom et al. 1987; Braden 1987) stages of ulcer from less to most severe. Prevalence estimates became a hospital-wide quality indicator. Risk profiles are used at unit level to plan intervention strategies (e.g., for moisture or mobility deficits). Outcomes indicating improvement rather than healing are also used (e.g., fewer of the severe ulcers using the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (1989) staging classification). One additional measure that has been added is the assessment of patient-reported pain with pressure ulcers (Girouard et al. 2008).

Work has continued to evaluate trends over time using the adverse event of pressure ulcer occurrence (Vandenkerkhof et al. 2005). Although helpful as a setting-wide indicator, prevalence estimates are limited in their usefulness to actual decision making in practice. Prevalence information does not shed light on when pressure ulcers are likely to occur, or the factors that contribute to their occurrence, deterioration, or improvement. To gain insight in these areas, ongoing, real-time, incidence data collection, rather than prevalence estimates, is required. Unlike prevalence performed as a one-shot cross-sectional effort, incidence data requires regular day-to-day tracking with established periodic analyses (weekly, monthly, and/or quarterly). This is particularly important for units with higher pressure ulcer occurrence. Although incidence rates have been periodically undertaken in our setting (Graham et al. 2004; Mackey et al. 2005), time and resource constraints continue to make this a challenge.

In the community leg ulcer example, outcomes were based on a combination of clinical and system-level concepts. In a 1-year prepost study (Harrison et al. 2005), the primary healing outcome, a 3-month healing rate, was selected for comparative and feasibility reasons. The 3-month rate for leg ulcer studies was used predominantly in the international literature. Importantly it was a practical outcome for the service team to collect and use with this slow healing wound. After implementation of the evidence-based protocol, healing more than doubled going from 23% to 56% (p = < 0.001) (Harrison et al. 2005). System outcomes, including the number of nursing visits per case, declined from a median of 37 to 25 (p = 0.041). The median supply cost per case was reduced from $1,923 to $406 Canadian (p = 0.005).

In a further study, undertaken by the same team, a randomized control trial compared and evaluated clinical and cost-effectiveness of home-versus-nurse clinic delivery of evidence-based care leg ulcer care using a health systems perspective (Harrison et al. 2008). In an era of economic constraints, this was a pressing issue for regional health-care authorities and home-nursing agencies in decisions about instituting nurse-led clinics for some client groups. In this trial we found no differences in the healing outcomes at 3 months (clinic 58.3%; home 56.7%) nor with any of the secondary outcomes which included durability of healing (time before next ulcer episode), recurrence within 1 year, health-related quality of life, patient satisfaction with care (short survey), and resource use (number of visits, supply expenditures). The study revealed that organizing care to deliver evidence-based care was key to achieving positive health and system outcomes not the location or setting of care (home versus clinic). Thus, regional community care authorities can use either home or clinic care to provide leg ulcer services and expect similar results. The modality of delivery is a decision on what may be appropriate for their community and resource availability.

Self-reported outcomes among individuals who are the recipients of care have become more important in leg ulcer implementation studies. Quality of life, satisfaction with care, and pain with this condition have been explored from a research perspective and integrated as part of the quality processes. The tools used to measure these outcomes are described in detail elsewhere but suffice to say they were selected for their clinical sensibility and feasibility. Health-related quality of life and pain are both measured with short form tools. For example, Nemeth and colleagues (2003a) adapted a rigorous process for assessing pain in this community population using a two-step method, followed by studies to examining impact of this symptom in order to improve nursing management (Nemeth et al. 2003b). The pain assessment method was embedded in the documentation so that it could be quality audited and nurse adherence to evidence recommendations followed as a natural course during the plan of care.

Our most recent trial related to the evidence-based leg ulcer program of research is focused on two high-compression technologies to establish which is superior (effective and efficient) in the community setting (Harrison et al. 2003). In this trial, a health services outcome was selected as most appropriate. This trial evaluated differences in healing with use of two common compression bandaging systems where the primary outcome was a 5-week or greater difference in healing. Clinically, time-to-healing is the outcome of choice and the 5-week difference serves as a health services outcome identified as relevant by service providers. The 5-week outcome was arrived at through consultation with home-care and nursing agency authorities and based on supply expenditures and nursing time involved in delivering each of these technologies. The 5-week difference in healing rates was deemed the tipping point to influence any decision to switch from one bandaging technology to the other. Otherwise, both would be considered effective and efficient and remain available on the supply inventories.

Limitations of different approaches

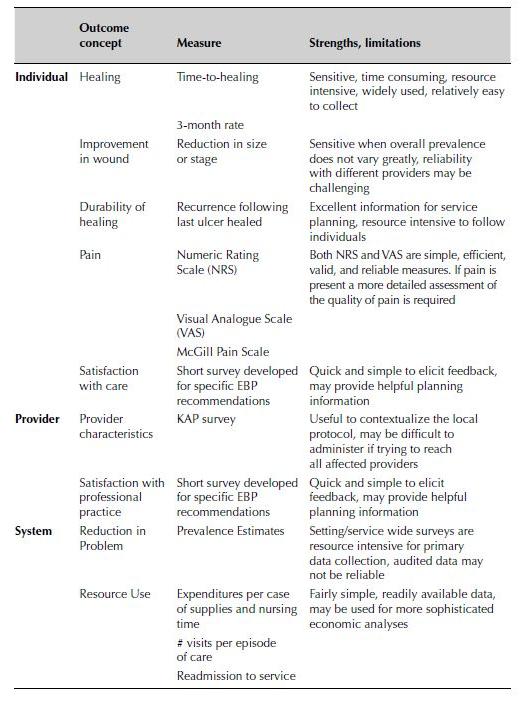

There are “pluses” and “minuses” of the various approaches to outcome assessment with an EBP implementation. One is typically trading off rigor with clinical sensibility and feasibility. One may want to conduct a full-scale resource use study but the practicality is that you have a limited amount of expenditure data in administrative databases that will be easy to capture and lend itself to modeling to impute full costs. In Table 5.1, a summary of the major outcomes used in the chronic wound implementations is provided with the strengths and limitations of the outcomes. It is important to remember that for any one outcome concept there are usually several means to capture the information. The best measure may carry too high a burden of administration presenting the risk of incomplete data for decision makers. The researcher, clinician, and decision-maker and service user perspectives should all be taken into account in selection of how to measure an outcome concept.

Table 5.1 Outcomes used with evidence-based practice implementation for two chronic wound populations (pressure ulcers and leg ulcers)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree