anticonvulsants, and chemotherapeutic agents can diminish or completely abolish the caloric response.5, 8 Loss of brainstem function also results in loss of breathing and vasomotor control, which results in apnea and hypotension to loss of blood pressure.

Preoxygenate with 100% FiO2 for 30 minutes.

Disconnect the patient from the ventilator (a PCO2 rise of 3 to 6 mm Hg/min is estimated in the apneic patient).

Immediately upon disconnection, place an oxygen cannula at the level of the carina and administer 100% oxygen at 9 to 12 L/min by tracheal cannula. Observe for respiratory movement of the chest/abdomen for 8 minutes (a respiration is defined as abdominal or chest movement that produces adequate tidal volume).

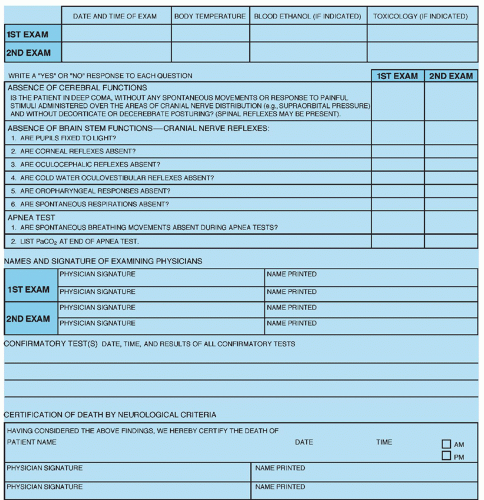

After 10 minutes, draw arterial blood gases. If there is no respiratory movement and the PCO2 is 60 mm Hg or higher, the clinical diagnosis of brain death is made. If the PCO2 has not met the target level of 60 mm Hg or higher, apnea testing is repeated after a period of time and confirmatory testing may also be ordered. Note that the target PCO2 may be higher in patients with chronic hypercapnia (e.g., severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, bronchiectasis, sleep apnea, morbid obesity) because the patient’s PCO2 baseline is higher. If chronic hypercapnia is suspected, additional noninvasive confirmatory tests are strongly recommended.5, 8

the patient. The nurse is often central in communications with the interdisciplinary practice team and interface with the family. Referrals may need to be made to the ethics committee, social worker, case manager, and others which include sharing of critical information. The interface with the family requires interpretation, clarification, and reinforcement of information throughout the process. It includes arranging for visitation and helping family in saying “good-bye” to the patient.

designed to support the nurse with necessary clear information to provide efficient and effective care for the patient and family.

TABLE 4-1 FIVE QUESTIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ADDRESSED IN 2010 UPDATE RELATED TO BRAIN DEATH | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree