Chapter 68 Complications of the third stage of labour

Postpartum haemorrhage

Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) is a significant cause of maternal mortality and morbidity (Knight et al 2008, Lewis 2007). It may happen without warning after any delivery. The only professional in attendance for the majority of births is the midwife, whose prompt action may spare the mother dangerous blood loss and save her life. It is essential that midwives have a thorough understanding of this subject. Maternity services must have a policy for management of PPH so that all members of the multidisciplinary team work together and attend regular ‘fire drills’ to ensure quick and appropriate responses (Lewis 2007).

Definition

Primary PPH is often defined by the estimated blood loss. Traditionally, a loss of 500 mL or more has been regarded as a PPH (WHO 1990), yet this may be considered as a normal physiological blood loss if a woman is not anaemic (Rogers & Chang 2008).

Estimating blood loss after birth is notoriously difficult. Bleeding may be hidden; and if visible, it is likely to be underestimated (Prasertcharoensuk et al 2000, Toledo et al 2007). However, regular clinical simulations may improve blood loss estimation (Bose et al 2006).

When estimating blood loss to define PPH, Coker & Oliver (2006) propose that if blood loss is estimated as 500 to 1000 mL and there are no clinical signs of maternal compromise, staff should be alerted to monitor the woman and be ready for possible action. Should the estimated blood loss be above 1000 mL or the mother shows any sign of compromise, then prompt action must be taken to resuscitate and arrest bleeding. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (2009) have used these principles to define minor and major PPH. The guidelines suggest that with a minor PPH (a blood loss of 500 to 1000 mL, with no maternal compromise) basic measures need to be undertaken, and when a major PPH is diagnosed (a blood loss of over 1000 mL or clinical shock present) a full obstetric protocol must be followed (see website).

PPH from uterine atony

The immediate cause of primary placental site PPH is failure of the uterus to contract and retract adequately. As there is a placental circulation of approximately 600 mL/min at term (Blackburn 2007), if the uterine arteries are not ligated by the muscle fibres surrounding them, blood loss can be rapid and dangerous. This may occur because the myometrium is atonic, or because retained placental tissue prevents effective uterine contraction.

Prediction and risk factors

It is not possible to predict a PPH accurately, but the risk is increased in certain circumstances:

Prophylaxis

Labour

During labour, careful management will reduce the likelihood of PPH. For women at risk:

The midwife will monitor the progress of labour and avoid dehydration and exhaustion. An obstetrician should be called for signs of prolonged labour (Ch. 63). An oxytocin infusion may be required which should be maintained for at least 1 hour after the end of the third stage. The bladder should be kept empty, as a full bladder may impede efficient uterine action.

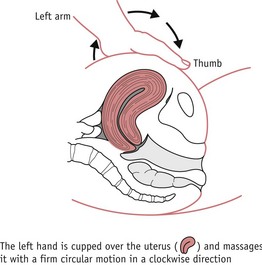

Correct management of the third stage of labour is crucial. The midwife should discuss the management of the third stage with the woman, preferably before labour commences. Active management of the third stage is associated with reduction in PPH (Prendiville et al 2000). The use of fundal massage following the delivery of the placenta is recommended to reduce the risk of PPH (Hofmeyr et al 2008). Breastfeeding or nipple stimulation will also help the uterus to contract, though it is not an effective treatment for PPH. Ergometrine maleate 500 mcg should be available. Accurate estimation of blood loss and timely observation of vital signs will enable early detection and prompt treatment.

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) (2005) guidelines suggest that women at risk of haemorrhage during or following caesarean section may be offered intra-operative blood cell salvage (see website). Guidelines for women who refuse blood transfusion have been recommended by a previous Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH) report (Lewis 2004) (see website).

Treatment

The principles of management are:

Units vary in the management of PPH, especially with pharmacological protocols (Winter et al 2007). This may be due to limited research on the specific treatment combinations for PPH. Midwives should follow their hospital guidelines as appropriate.

Before delivery of the placenta

The degree of uterine contraction should be assessed. If the fundus feels soft, the first consideration is to stimulate uterine contraction and give an oxytocic drug. Oxytocin 10 international units (iu) may be given intramuscularly, causing the uterus to contract within 2.5 minutes. Syntometrine (oxytocin 5 iu and ergometrine 500 mcg) should be avoided if there is a history of hypertension. There is also some evidence that ergometrine may cause the placenta to become entrapped (Begley 1990, Cotter et al 2001, Hammar et al 1990), thus exacerbating the bleeding.

After delivery of the placenta

Intravenous or intramuscular injection of oxytocin 5–10 iu followed by ergometrine 250–500 mcg. This may be given intramuscularly or, cautiously, intravenously in the absence of hypertension. No more than two doses of ergometrine may be administered (Joint Formulary Committee 2008).

Intravenous or intramuscular injection of oxytocin 5–10 iu followed by ergometrine 250–500 mcg. This may be given intramuscularly or, cautiously, intravenously in the absence of hypertension. No more than two doses of ergometrine may be administered (Joint Formulary Committee 2008).Further measures

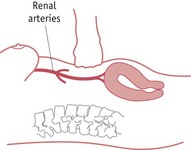

Abdominal aortic compression

This has been used as a short-term emergency measure to control severe haemorrhage while awaiting emergency assistance. The midwife places a fist above the fundus and below the level of the renal arteries. Pressure is directed towards the spine in order to compress the aorta and reduce blood flow to the uterus (Fig. 68.4). Adequacy of compression can be assessed by checking for the absence of femoral pulses (Keogh & Tsokos 1997).

Massive obstetric haemorrhage

In addition to the measures taken above for a minor PPH, the following should be done:

Carboprost (Hemabate) 250 mcg may be administered by deep intramuscular injection and can be repeated every 15 minutes, up to eight doses (maximum dosage of 2 mg) (Joint Formulary Committee 2008). It may also be injected directly into the myometrium.

Carboprost (Hemabate) 250 mcg may be administered by deep intramuscular injection and can be repeated every 15 minutes, up to eight doses (maximum dosage of 2 mg) (Joint Formulary Committee 2008). It may also be injected directly into the myometrium.Surgical procedures

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree