Discuss the need for vitamin and mineral supplements.

Describe the use of vitamins and minerals in specific groups of patients.

Describe the use of vitamins and minerals in specific groups of patients.

Identify fat-soluble vitamins used to treat deficiencies, including the nursing implications associated with their administration.

Identify fat-soluble vitamins used to treat deficiencies, including the nursing implications associated with their administration.

Identify water-soluble vitamins used to treat deficiencies, including the nursing implications associated with their administration.

Identify water-soluble vitamins used to treat deficiencies, including the nursing implications associated with their administration.

Identify minerals used to treat deficiencies, including the nursing implications associated with their administration.

Identify minerals used to treat deficiencies, including the nursing implications associated with their administration.

Discuss the chelating agents used to remove excess copper, iron, and lead from body tissue:

Discuss the chelating agents used to remove excess copper, iron, and lead from body tissue:

Recognize the benefit of nutritional supplements, including the nursing implications associated with their administration.

Recognize the benefit of nutritional supplements, including the nursing implications associated with their administration.

Apply nursing process skills to prevent, recognize, or treat nutritional imbalances, which may involve monitoring laboratory reports that indicate nutritional status.

Apply nursing process skills to prevent, recognize, or treat nutritional imbalances, which may involve monitoring laboratory reports that indicate nutritional status.

Clinical Application Case Study

Jenny Martin, an 86-year-old woman, has lived alone for 10 years since her husband died. She sometimes must limit her food purchases to pay for her medicines and utilities. Thus, her nutritional status is poor. A neighbor, who has not seen Mrs. Martin for a couple of days, finds her conscious on the kitchen floor but with slurred speech. Emergency medical personnel transport her to a hospital emergency department, where she is diagnosed with a left brain stroke with right hemiparesis, dysarthria, and dysphagia.

Mrs. Martin is unable to swallow foods safely, so the nurses insert a nasogastric tube. A dietician orders a high-calorie commercially prepared formula that contains carbohydrates, protein, fat, vitamins, and minerals.

KEY TERMS

Chelating agents: drugs used to treat metal poisoning (e.g., from iron, lead, or mercury) that bind to the toxic metal, decrease binding of the metal within the body, and promote elimination of the metal

Electrolytes: electrically charged particles found in body fluids and cells (e.g., sodium or potassium ions)

Enteral nutrition: provision of fluid and nutrients to a functional gastrointestinal tract via a feeding tube in a patient who is unable to ingest enough fluid and food

Fat-soluble vitamins: vitamins that are accumulated and stored in the body when taken in excess

Hyperkalemia: greater than normal amount of potassium in the blood

Hypokalemia: less than normal amount of potassium in the blood

Malabsorption: impaired absorption of nutrients from the gastrointestinal tract

Megaloblastic anemia: anemia characterized by the presence in the blood of megaloblasts (large, abnormal blood cells); associated with vitamin B12 deficiency

Megavitamins: large dose of vitamins in excess of the recommended dietary allowance

Parenteral nutrition: intravenous provision of fluid and nutrients to a patient who is unable to ingest enough fluid and food due to a nonfunctional gastrointestinal tract

Water-soluble vitamins: vitamins that are not stored in the body and are rapidly eliminated

Introduction

Water, carbohydrates, proteins, fats, vitamins, and minerals are required to promote or maintain health, to prevent illness, and to promote recovery from illness or injury. Water is necessary for cellular metabolism and excretion of metabolic waste products; people need 2000 to 3000 mL daily. Carbohydrates and fats mainly provide energy for cellular metabolism. Energy is measured in kilocalories (kcal) per gram of food oxidized in the body. Carbohydrates and proteins supply 4 kcal/g; fats supply 9 kcal/g. Proteins are structural and functional components of all body tissues; the recommended amount for adults is 50 to 60 g daily.

Vitamins are required for normal body metabolism, growth, and development. They are components of enzyme systems that release energy from ingested carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. They also are necessary for formation of genetic material, red blood cells, hormones, nerve cells, and bone and other tissues. Minerals and electrolytes are essential constituents of cell membranes, many essential enzymes, bone, teeth, and connective tissue. They function to maintain electrolyte and acid-base balance, maintain osmotic pressure, maintain nerve and muscle function, assist in transfer of compounds across cell membranes, and influence the growth process.

Patients’ requirements for these nutrients vary widely, depending on age, sex, size, health or illness status, and other factors. This chapter discusses medications and products to improve nutritional status in patients with deficiency states and excess states of selected vitamins, minerals, and electrolytes.

Overview of Altered Nutritional States

Etiology

Many patients may be unable to ingest, digest, absorb, or use sufficient nutrients to improve or maintain health. Debilitating illnesses often interfere with appetite and gastrointestinal (GI) function. Drugs often cause anorexia, nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea. The lack of certain vitamins and minerals may impair the function of body organs. Genetic disorders or traumatic injury may also affect nutritional status.

Pathophysiology

Dietary intake must provide required amino acids, fatty acids, and lipids, as well as vitamins and minerals. Both deficient and excess amounts of these nutrients adversely influence health. Nutritional status directly affects enzyme function, immune response, and wound healing.

Vitamins

Vitamins are organic compounds that help release energy from carbohydrates, fats, and proteins. They are necessary for the formation of genetic materials, red blood cells, hormones, and the nervous system, as well as for normal growth and development.

There are two types of vitamins: fat soluble and water soluble. Fat-soluble vitamins—vitamins A, D, E, and K—are stored in the body when taken in excess. They are absorbed from the intestine with dietary fat. Absorption requires the presence of bile salts and pancreatic lipase. (Note that vitamin D is discussed in Chap. 42 because of its major role in bone metabolism.) Water-soluble vitamins—B complex vitamins and vitamin C—are not stored in the body and are rapidly eliminated.

People can obtain vitamins from foods or supplements. Although experts believe foods to be the best source, studies indicate that most adults and children do not consume enough fruits, vegetables, cereal grains, dairy products, and other foods to consistently meet their vitamin requirements. In addition, some conditions increase requirements above the recommended amounts (e.g., pregnancy, lactation, and various illnesses). Historically, the major concern about vitamins concerned whether a person’s intake was sufficient to promote health and prevent deficiency diseases. Hence, the Food and Nutrition Board of the National Academy of Sciences established recommendations for daily vitamin intake known as Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) (Box 33.1).

BOX 33.1 Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs)

Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) are the recommended amounts of vitamins (see Table 33.1) and some minerals (see Table 33.2). The Food and Nutrition Board of the Institute of Medicine revised the current DRIs in 2006; the board intended them to replace the recommended dietary allowances (RDAs) used since 1989. DRIs consist of four subtypes of nutrient recommendations, as follows:

1. Recommended dietary allowance (RDA) is the amount estimated to meet the needs of approximately 98% of healthy children and adults in a specific age and gender group. The RDA is used to advise various groups about nutrient intake. It should be noted, however, that RDAs were established to prevent deficiencies and that they were extrapolated from studies of healthy adults. Thus, they may not be appropriate for all groups, such as young children and older adults.

2. Estimated average requirement (EAR) is the amount estimated to provide adequate intake in 50% of healthy persons in a specific group. The EAR is a median amount that takes into account the bioavailability of the nutrient and reduction of chronic disease. The EAR is used to determine the RDA.

3. Adequate intake (AI) is the amount thought to be sufficient when there is not enough reliable, scientific information to estimate an RDA. The AI is derived from data that show an average intake that appears to maintain health. Although an RDA is expected to meet the needs of all healthy people, an AI does not clearly indicate the percentage of people whose needs will be met.

4. Tolerable upper intake level (UL) is the maximum intake considered unlikely to pose a health risk in almost all healthy people in a specified group. The UL is not intended to be a recommended level of intake.

Vitamins. The ULs for adults (ages 19-70 years and older) are D 50 mcg, E 1000 mg, B3 (niacin) 35 mg, B6 (pyridoxine) 100 mg, folate 1000 mcg, and C 2000 mg. With vitamin D, pyridoxine, and vitamin C, the UL refers to total intake from food, fortified food, and supplements. With niacin and folate, the UL applies to synthetic forms obtained from supplements, fortified food, or a combination of the two. With vitamin E, the UL applies to any form of supplemental alpha-tocopherol. These ULs should not be exceeded. There are inadequate data for establishing ULs for B, (thiamine), B2 (riboflavin), B5 (pantothenic acid), B12 (cyanocobalamin), and biotin. As a result, consuming more than the recommended amounts of these vitamins should generally be avoided.

Vitamins. The ULs for adults (ages 19-70 years and older) are D 50 mcg, E 1000 mg, B3 (niacin) 35 mg, B6 (pyridoxine) 100 mg, folate 1000 mcg, and C 2000 mg. With vitamin D, pyridoxine, and vitamin C, the UL refers to total intake from food, fortified food, and supplements. With niacin and folate, the UL applies to synthetic forms obtained from supplements, fortified food, or a combination of the two. With vitamin E, the UL applies to any form of supplemental alpha-tocopherol. These ULs should not be exceeded. There are inadequate data for establishing ULs for B, (thiamine), B2 (riboflavin), B5 (pantothenic acid), B12 (cyanocobalamin), and biotin. As a result, consuming more than the recommended amounts of these vitamins should generally be avoided.

Minerals. ULs have been established for magnesium 350 mg, calcium 2.5 g, phosphorus 3 to 4 g, fluoride 10 mg, and selenium 400 mcg. The UL should not be exceeded for any mineral-electrolyte because all minerals are toxic in overdose. Except for magnesium, which is set for supplements only and excludes food and water sources, the stated UL amounts include those from both food and supplements.

Minerals. ULs have been established for magnesium 350 mg, calcium 2.5 g, phosphorus 3 to 4 g, fluoride 10 mg, and selenium 400 mcg. The UL should not be exceeded for any mineral-electrolyte because all minerals are toxic in overdose. Except for magnesium, which is set for supplements only and excludes food and water sources, the stated UL amounts include those from both food and supplements.

Vitamin deficiencies occur as a result of inadequate intake or disease processes that interfere with absorption or use of vitamins. Excess states occur with excessive intake of fat-soluble vitamins because these vitamins accumulate in the body. Excess states do not occur with dietary intake of water-soluble vitamins but may occur with vitamin supplements that exceed recommended amounts.

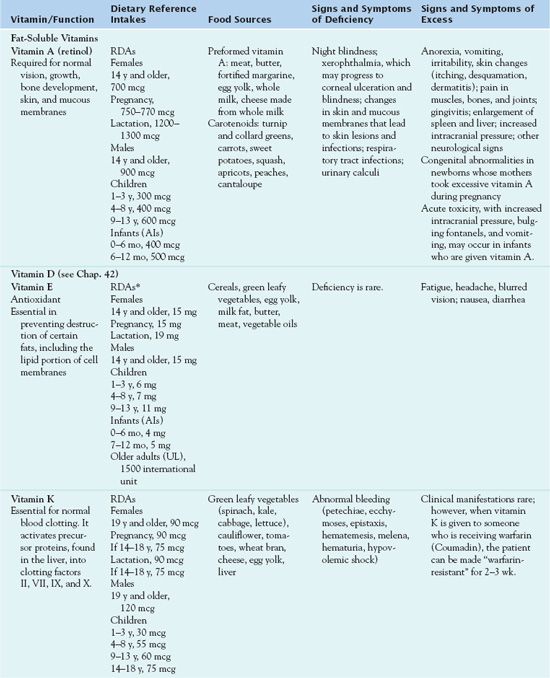

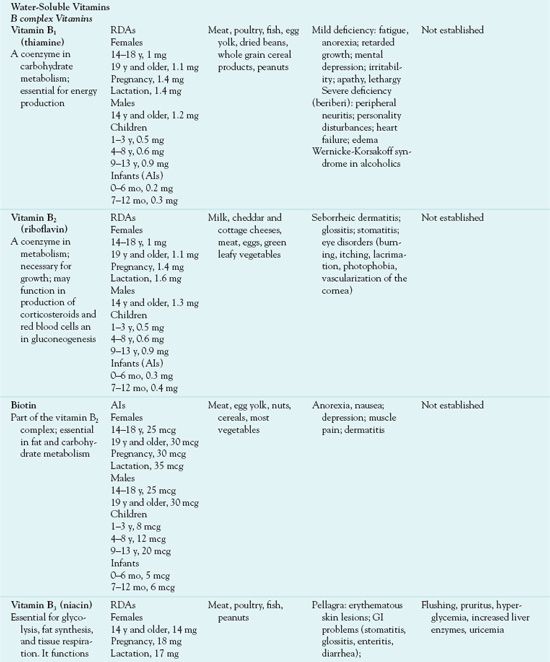

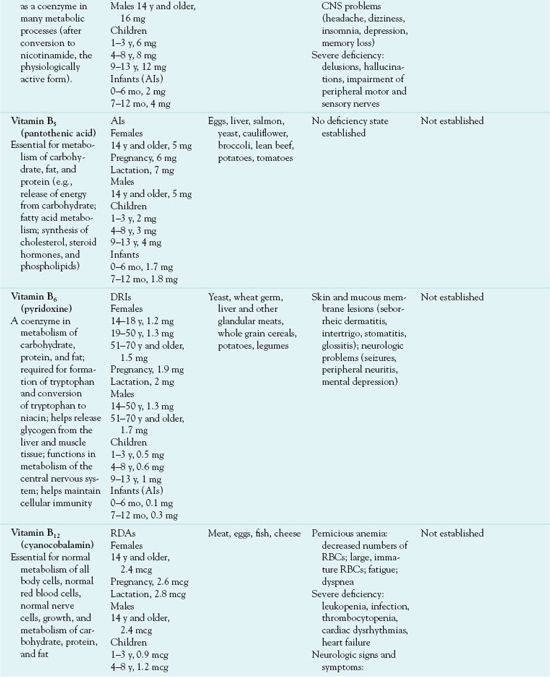

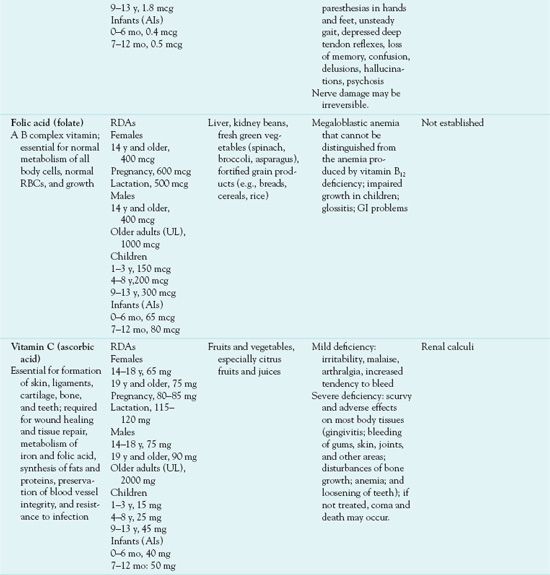

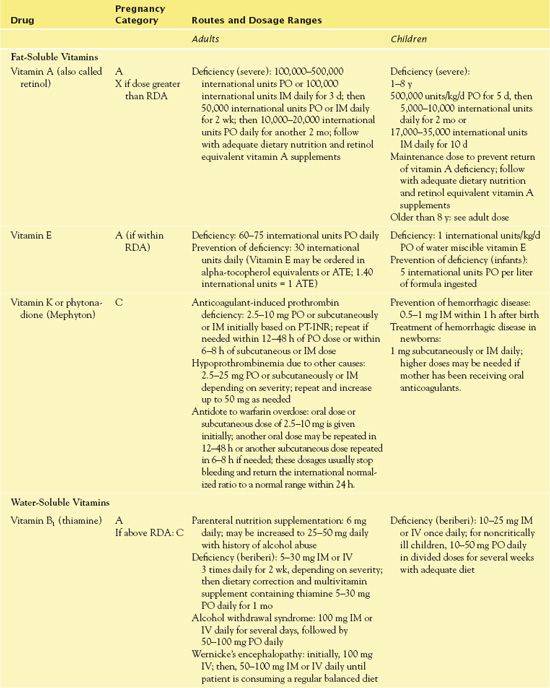

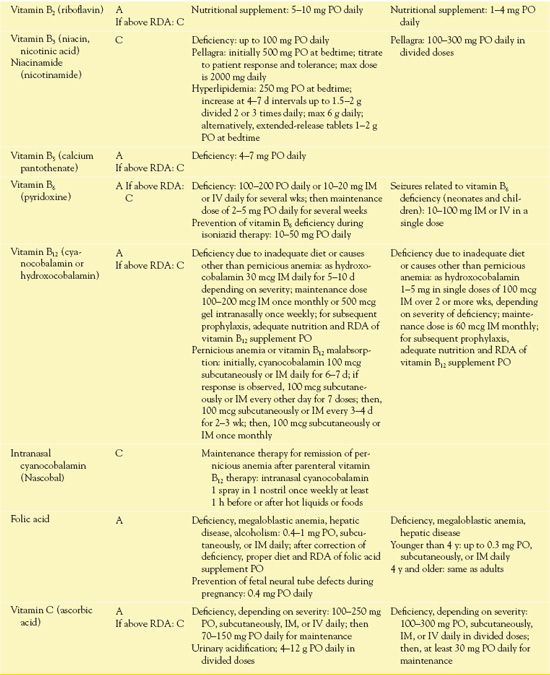

Many authorities promote vitamin supplements as a means to improve health and prevent or treat illness. However, supplements can be harmful if overused. As a result, DRIs include tolerable upper intake levels (ULs) of some vitamins. Table 33.1 lists the function, recommended daily intake, food sources, and signs and symptoms of deficiency and excess of vitamins.

*Vitamin E activity is expressed in milligrams of alpha-tocopherol equivalents (alpha TE).

AI, adequate intake; DRI, Dietary Reference Intake; GI, gastrointestinal; RBC, red blood cell; RDA, recommended dietary allowance.

QSEN Safety Alert

No one should take more than the recommended ULs.

Although health care providers may order vitamin supplements, people mostly self-prescribe them. Because vitamins are essential nutrients, some people believe that large amounts (megadoses) promote health and provide other beneficial effects. However, excessive intake may cause harmful effects. People should never self-prescribe megavitamins, large doses of vitamins in excess of the recommended dietary allowance (RDA). Additional characteristics of vitamins include the following:

• Vitamins from supplements have the same physiological effects as those obtained from foods.

• Synthetic vitamins have the same structure and function as natural vitamins derived from plant and animal sources and are less expensive.

• Vitamin supplements do not require a prescription.

• Vitamin products vary widely in number, type, and amount of specific ingredients.

• Preparations should not contain more than the recommended amounts of vitamin A, vitamin D, and folic acid (a B complex vitamin).

• Multivitamin preparations often contain minerals as well. Large doses of all minerals are toxic.

• Vitamins are often marketed in combination products with each other (e.g., antioxidant vitamins) and with herbal products (e.g., B complex vitamins with ginseng). There is no reliable evidence to support the use of such products.

Some people believe that some vitamins (e.g., the vitamin A precursor beta carotene, vitamin E, and vitamin C), with their antioxidant effects, prevent heart disease, cancer, and other illnesses. Antioxidants inactivate oxygen free radicals, which are potentially toxic substances formed during normal cell metabolism, and inhibit them from damaging body cells. However, the results of most research studies with antioxidant vitamin supplements have been disappointing and inconclusive. The consensus view is that dietary vitamins from several daily servings of grains, fruits, and vegetables and a daily multivitamin supplement are beneficial for most children and adults, but it is not possible to make recommendations about vitamin supplements to prevent various chronic illnesses on the basis of current evidence. Because parents’ desires to promote health may lead them to give children unneeded supplements or to give them more than recommended amounts, it may be necessary to give parents information about the potential hazards of vitamin overdoses.

Minerals

Minerals maintain acid-base balance and osmotic pressure. They make up part of enzymes, hormones, and vitamins. The body needs minerals for hemoglobin formation, muscle contraction, and skeletal development and maintenance. Minerals present in the body in large amounts (macrominerals) are sodium, potassium, chloride, calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, and sulfur. (Note: Calcium and phosphorus are discussed in Chapter 42 because they play major roles in bone metabolism.) Other minerals are required in small amounts (trace elements). Eight of these (chromium, cobalt, copper, fluoride, iodine, iron, selenium, and zinc) have relatively well-defined roles in human nutrition.

Minerals occur in the body and foods mainly in ionic form. When placed in solution, the components separate into electrolytes. Electrolytes are electrically charged particles found in body fluids and cells (e.g., sodium or potassium ions). At any given time, the body must maintain an equal number of positive and negative charges. Therefore, the ions are constantly combining and separating to maintain electrical neutrality or electrolyte balance.

Electrolytes also maintain the acid-base balance of body fluids. Acids are usually anions (e.g., bicarbonate, chloride, phosphate, or sulfate). Bases are usually cations (e.g., sodium, potassium, calcium, and magnesium). Mineral-electrolytes are obtained from foods or supplements. Although most minerals are supplied by a well-balanced diet, studies indicate that most adults and children do not ingest sufficient dietary calcium and that iron deficiency is common in some populations. In addition, some conditions increase requirements (e.g., pregnancy, lactation, and various illnesses) and some drug-drug interactions decrease absorption or use of minerals.

As with vitamins, goals for daily mineral intake have been established as DRIs. Thus far, DRIs and ULs have been established for calcium, fluoride, iron, magnesium, phosphorus, and selenium.

QSEN Safety Alert

People should not exceed the UL for any mineral-electrolyte.

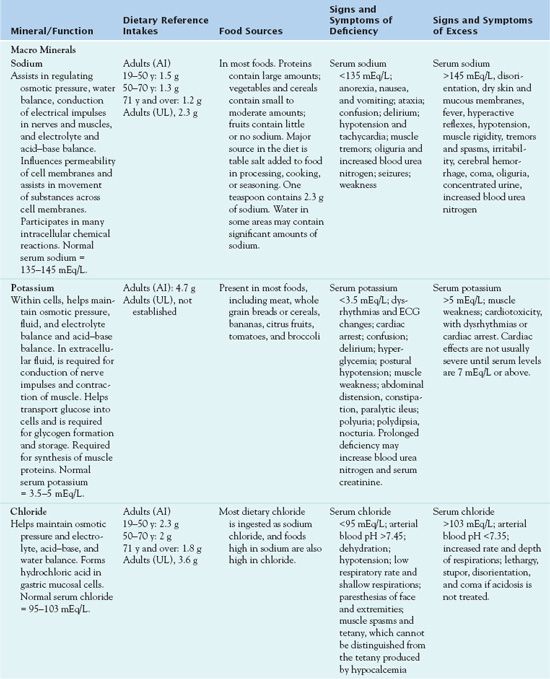

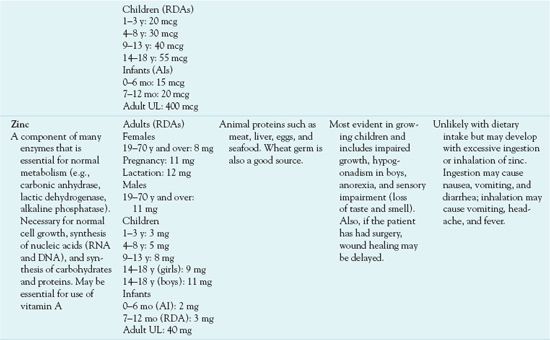

Except for the stated amount for magnesium, which excludes food and water sources and considers supplements only, the ULs include those from both foods and supplements. Table 33.2 lists the function, recommended daily intake, and dietary sources of various minerals.

AI, adequate intake; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; DRI, Dietary Reference Intake; RDA, recommended dietary allowance.

• Multivitamin-mineral combinations recommended for age and gender groups contain different amounts of some minerals (e.g., younger women need more iron than postmenopausal women). It is necessary to consider this when choosing a product.

• Iron supplements other than those in multivitamin-mineral combinations are usually intended for temporary use in the presence of deficiency or a period of increased need (e.g., pregnancy). People should not take them otherwise because of risks of accumulation and toxicity.

• Most adolescent and adult females probably benefit from a calcium supplement to achieve the recommended amount (1000-1300 mg daily). It is important to consider the amounts consumed in dairy products and other foods and not exceed the UL of 2500 mg daily.

Clinical Manifestations

Tables 33.1 and 33.2 list signs and symptoms associated with deficiency and excess of vitamins and minerals, respectively.

Drug Therapy

Early recognition and treatment of vitamin disorders can prevent a mild deficiency or excess from becoming severe. For deficiency states, oral vitamin preparations are preferred when possible. Multiple deficiencies are common, and a multivitamin preparation used to treat them usually contains more than the recommended daily amount. Use for limited periods is best. When fat-soluble vitamins are given to correct a deficiency, there is a risk of producing excess states. When water-soluble vitamins are given, excesses are less likely but may occur with large doses. For excess states, the usual treatment is to stop administration of the vitamin preparation. There are no specific antidotes or antagonists.

It is important to titrate the amount of mineral supplement closely to the amount needed by the body as there is a risk of producing an excess state. Oral products are preferred for replacement because they are safer, less likely to produce toxicity, more convenient to administer, and less expensive than parenteral preparations. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates content of supplements for infants and children younger than 4 years of age; however, it does not regulate the content of preparations for older children.

Children

Children need sufficient amounts of vitamins and minerals to support growth and normal body functioning. Dosages should not exceed recommended amounts. For infants (birth to 12 months), the only UL is for vitamin D. For other children, ULs vary according to age. A combined vitamin-mineral supplement every other day may be reasonable, especially for children who eat poorly.

There is a risk of overdose in children; this risk is more serious with the fat-soluble vitamins because they are stored long-term within the body. Also, all minerals and electrolytes are toxic in overdose. Because of manufacturers’ marketing strategies, many supplements are available in flavors and shapes (e.g., animals, cartoon characters) designed to appeal to children.

QSEN Safety Alert

Because younger children may think of these supplements as candy and take more than recommended, it is essential that they be stored out of reach and dispensed by an adult.

Older Adults

Vitamin requirements are the same for older adults as for younger adults, but deficiencies are common, especially with the fat-soluble vitamins A and D. It is important to assess every older adult regarding vitamin intake (from food and supplements) and use of drugs that interact with dietary nutrients. For most older adults, a daily multivitamin is probably desirable, even for those who seem healthy and able to eat a well-balanced diet. In addition, requirements may be increased during illnesses, especially those affecting GI function. Overdoses, especially of the fat-soluble vitamins A and D, may cause toxicity; it is necessary to avoid this.

Renal and Hepatic Impairment

Patients with acute renal failure who are unable to eat an adequate diet need a vitamin supplement to meet DRIs. Overall, a multivitamin with essential vitamins is recommended for daily use. Decreased renal function may promote mineral retention.

QSEN Safety Alert

It is important to monitor serum electrolyte levels f closely and provide supplements only with great care.

Vitamin deficiencies commonly occur in patients with chronic liver disease, because of poor intake and malabsorption (impaired absorption of nutrients from the GI tract). Hepatic failure results in depletion of hepatic stores of vitamin A and other vitamins.

Critical Illness

Critically ill patients often have organ failure, which alters their ability to ingest and use essential nutrients. They may be undernourished with regard to vitamins and minerals. The Nutrition Advisory Group of the American Medical Association has established guidelines for daily intake, and parenteral multivitamin formulations are available for adults and children. Close monitoring of serum electrolytes is necessary.

Clinical Application 33-1

Identify findings in the assessment of Mrs. Martin that would put her at risk for vitamin, mineral, and nutritional deficiency.

Identify findings in the assessment of Mrs. Martin that would put her at risk for vitamin, mineral, and nutritional deficiency.

NCLEX Success

1. Which one of the following findings in a nursing assessment of a newly admitted patient would be most likely to result in a vitamin deficiency?

A. a history of liver disease

B. use of self-prescribed megavitamins

C. presence of a pressure ulcer

D. frequent blood transfusions

2. A woman takes large amounts of vitamins, which she buys over the counter without a prescription. The nurse should teach the patient that excess consumption of which one of the following could result in a toxic overdose?

A. folic acid

B. vitamin A

C. vitamin B1

D. vitamin C

Fat-Soluble Vitamins

VITAMIN A

The following discussion concerns vitamin A, or retinol.

Pharmacokinetics and Use

After oral administration, vitamin A is absorbed from the GI tract along with dietary fat and is primarily stored in the liver. The body can store up to a year’s supply of vitamin A in the liver. This vitamin, which is not soluble in the blood, is distributed by attaching to protein carriers in the blood. If a person consumes inadequate amounts of vitamin A, the body uses the vitamin stored in the liver. Vitamin A is metabolized in the liver and eliminated in the feces and urine.

The most important therapeutic use of vitamin A is for replacement in deficiency states. Table 33.3 gives route and dosage information.

TABLE 33.3

TABLE 33.3

Adverse Effects and Contraindications

Signs and symptoms of vitamin A toxicity include hair loss, double vision, headaches, vomiting, bone abnormalities, and liver damage. If any signs or symptoms of vitamin A excess appear, it is necessary to stop intake of any known sources of vitamin A.

Contraindications to vitamin A include a history of allergic reaction to the vitamin, hypervitaminosis A, and malabsorption syndrome (oral use only). Caution is warranted in pregnancy. Vitamin A toxicity during pregnancy can cause fetal defects (Dudek, 2010).

Nursing Implications

Preventing Interactions

Chronic use of mineral oil or bile acid sequestrants may cause vitamin A deficiency by preventing systemic absorption of vitamin A. Mineral oil combines with fat-soluble vitamins and prevents their absorption if both are taken at the same time. Bile salts increase the effects of vitamin A by increasing intestinal absorption of the vitamin. Large doses of vitamin A may increase the anticoagulant effects of warfarin. Antibiotics may cause diarrhea and subsequent malabsorption of vitamin A.

Administering the Medication

People should take vitamin A preparations before meals, on an empty stomach. However, to prevent nausea, it may be necessary to take them after food or meals. (Intramuscular [IM] administration may be necessary.) Also, people should not take oral preparations of vitamin A at the same time as mineral oil; this laxative absorbs the vitamin and thus prevents its systemic absorption.

Assessing for Therapeutic and Adverse Effects

The nurse observes for decreased signs and symptoms of deficiency, such as improved vision, especially in dim light or at night; less dryness in eyes and conjunctiva (xerophthalmia); and improvement in skin lesions. Night blindness is usually better within a few days. Skin lesions may not disappear for several weeks.

In addition, the nurse observes for signs of hypervitaminosis A, such as anorexia, vomiting, irritability, headache, skin disorders, and pain in muscles, bones, and joints. Serum levels of vitamin A greater than 1200 international unit/dL are toxic. Severity of manifestations depends largely on dose and duration of excess vitamin A intake. Very severe states produce additional clinical signs, including enlargement of the liver and spleen, altered liver function, increased intracranial pressure, and other neurologic manifestations.

Patient Teaching

Box 33.2 identifies patient teaching guidelines for vitamins, including vitamin A.

BOX 33.2  Patient Teaching Guidelines for Vitamins

Patient Teaching Guidelines for Vitamins

General Considerations

Certain people may need vitamin supplements. Women who are pregnant, as well as people who smoke, ingest large amounts of alcohol, have impaired immune systems, or are elderly may need to take oral vitamins.

Certain people may need vitamin supplements. Women who are pregnant, as well as people who smoke, ingest large amounts of alcohol, have impaired immune systems, or are elderly may need to take oral vitamins.

Avoid taking large doses of vitamins, which do not promote health, strength, or youth.

Avoid taking large doses of vitamins, which do not promote health, strength, or youth.

Natural vitamins are advertised as being better than synthetic vitamins, but there is no evidence to support this claim. The two types are chemically identical, and the body uses them the same way. Natural vitamins are more expensive.

Natural vitamins are advertised as being better than synthetic vitamins, but there is no evidence to support this claim. The two types are chemically identical, and the body uses them the same way. Natural vitamins are more expensive.

Vitamins from supplements exert the same physiological effects as those obtained from foods.

Vitamins from supplements exert the same physiological effects as those obtained from foods.

Multivitamin preparations often contain minerals as well, usually in smaller amounts than those recommended for daily intake. Large doses of minerals are toxic.

Multivitamin preparations often contain minerals as well, usually in smaller amounts than those recommended for daily intake. Large doses of minerals are toxic.

Supplementary vitamin preparations differ widely in amounts and types of vitamin content.

Supplementary vitamin preparations differ widely in amounts and types of vitamin content.

When choosing a vitamin supplement, compare ingredients and costs. Store brands are usually effective and less expensive than name brands.

When choosing a vitamin supplement, compare ingredients and costs. Store brands are usually effective and less expensive than name brands.

Vitamin A

Know about dietary sources of vitamin A. Retinol occurs in liver, milk, butter, cheese, cream, egg yolk, fortified milk, margarine, and ready-to-eat cereals. Beta carotenes occur in spinach, collard greens, kale, mango, broccoli, carrots, peaches, pumpkin, red peppers, sweet potatoes, winter squash, watermelon, apricots, and cantaloupe.

Know about dietary sources of vitamin A. Retinol occurs in liver, milk, butter, cheese, cream, egg yolk, fortified milk, margarine, and ready-to-eat cereals. Beta carotenes occur in spinach, collard greens, kale, mango, broccoli, carrots, peaches, pumpkin, red peppers, sweet potatoes, winter squash, watermelon, apricots, and cantaloupe.

Understand that excessive amounts of vitamin A are stored in the body and often lead to toxic effects. High doses of vitamin A can result in headaches; diarrhea; nausea; loss of appetite; dry, itching skin; and elevated blood calcium.

Understand that excessive amounts of vitamin A are stored in the body and often lead to toxic effects. High doses of vitamin A can result in headaches; diarrhea; nausea; loss of appetite; dry, itching skin; and elevated blood calcium.

Do not take a supplementary vitamin product that contains more than recommended amounts of vitamin A because of possible adverse effects.

Do not take a supplementary vitamin product that contains more than recommended amounts of vitamin A because of possible adverse effects.

If you are pregnant or could become pregnant, know that excessive doses of vitamin A during pregnancy may cause birth defects.

If you are pregnant or could become pregnant, know that excessive doses of vitamin A during pregnancy may cause birth defects.

Vitamin E

Know about dietary sources of vitamin E. This vitamin occurs in vegetable oils, margarine, salad dressing, other foods made with vegetable oil, nuts, seeds, wheat germ, dark green vegetables, whole grains, and fortified cereals.

Know about dietary sources of vitamin E. This vitamin occurs in vegetable oils, margarine, salad dressing, other foods made with vegetable oil, nuts, seeds, wheat germ, dark green vegetables, whole grains, and fortified cereals.

Be familiar with the signs and symptoms of vitamin E overdose.

Be familiar with the signs and symptoms of vitamin E overdose.

Do not take a supplementary vitamin product that contains more than the recommended amounts of vitamin E.

Do not take a supplementary vitamin product that contains more than the recommended amounts of vitamin E.

Vitamin K

Know about dietary sources of vitamin K. This vitamin occurs in spinach, brussels sprouts, broccoli, cabbage, cauliflower, Swiss chard, lettuce, collard greens, carrots, green beans, asparagus, and eggs.

Know about dietary sources of vitamin K. This vitamin occurs in spinach, brussels sprouts, broccoli, cabbage, cauliflower, Swiss chard, lettuce, collard greens, carrots, green beans, asparagus, and eggs.

Avoid excessive doses of vitamin K. Take this vitamin only as directed by a health care provider.

Avoid excessive doses of vitamin K. Take this vitamin only as directed by a health care provider.

Keep intake of vitamin K-containing foods constant. Avoid sudden increases or decreases in the amounts of these foods.

Keep intake of vitamin K-containing foods constant. Avoid sudden increases or decreases in the amounts of these foods.

If you are taking warfarin, report any use of vitamin K to your health care provider. During warfarin therapy, intake of vitamin K-containing foods should remain constant.

If you are taking warfarin, report any use of vitamin K to your health care provider. During warfarin therapy, intake of vitamin K-containing foods should remain constant.

Vitamin B1, Vitamin B3, and Vitamin B6

Know about dietary sources of vitamins B, (thiamine), B3 (niacin), and B6 (pyridoxine). Thiamine occurs in whole grain and enriched breads and cereals, liver, nuts, wheat germ, pork, and dried peas and beans. Niacin occurs in all protein foods and whole grain and enriched breads and cereals. Pyridoxine occurs in meats, fish, poultry, fruits, green leafy vegetables, whole grains, and dried peas and beans.

Know about dietary sources of vitamins B, (thiamine), B3 (niacin), and B6 (pyridoxine). Thiamine occurs in whole grain and enriched breads and cereals, liver, nuts, wheat germ, pork, and dried peas and beans. Niacin occurs in all protein foods and whole grain and enriched breads and cereals. Pyridoxine occurs in meats, fish, poultry, fruits, green leafy vegetables, whole grains, and dried peas and beans.

Swallow extended-release products whole; do not break, crush, or chew them. Breaking the product delivers the entire dose at once and may cause adverse effects.

Swallow extended-release products whole; do not break, crush, or chew them. Breaking the product delivers the entire dose at once and may cause adverse effects.

Take oral niacin preparations, except for timed-release forms, with or after meals or at bedtime to decrease stomach irritation.

Take oral niacin preparations, except for timed-release forms, with or after meals or at bedtime to decrease stomach irritation.

After taking a dose of oral niacin, sit or lie down for approximately 30 minutes after taking a dose. Niacin causes blood vessels to dilate and may cause facial flushing, dizziness, and falls. Facial flushing can be decreased by taking aspirin 325 mg orally, 30 to 60 minutes before a dose of niacin (if aspirin is not contraindicated). Itching, tingling, and headache may occur. These effects usually subside with continued use of niacin.

After taking a dose of oral niacin, sit or lie down for approximately 30 minutes after taking a dose. Niacin causes blood vessels to dilate and may cause facial flushing, dizziness, and falls. Facial flushing can be decreased by taking aspirin 325 mg orally, 30 to 60 minutes before a dose of niacin (if aspirin is not contraindicated). Itching, tingling, and headache may occur. These effects usually subside with continued use of niacin.

Vitamin B12 and Folic Acid

Know about dietary sources of vitamin B12. This vitamin occurs in meat, fish, poultry, shellfish, milk, dairy products, eggs, and some fortified foods.

Know about dietary sources of vitamin B12. This vitamin occurs in meat, fish, poultry, shellfish, milk, dairy products, eggs, and some fortified foods.

Vitamin B12 does not occur in plant sources. If you are a strict vegan who consumes no animal products, you are at risk for vitamin B12 deficiency unless you take a supplementary source of the vitamin.

Know about dietary sources of folic acid. This nutrient occurs in liver, okra, spinach, asparagus, dried peas and beans, seeds, and orange juice. Breads, cereals, and other grains are fortified with folic acid.

Know about dietary sources of folic acid. This nutrient occurs in liver, okra, spinach, asparagus, dried peas and beans, seeds, and orange juice. Breads, cereals, and other grains are fortified with folic acid.

Take prescribed vitamins as directed and for the appropriate time. If you have pernicious anemia, you must have vitamin B12 injections for the remainder of your life. Any chronic vitamin B12 deficiency requires lifelong treatment. If you are pregnant or breastfeeding, requirements may be greater; you usually may need additional vitamin supplements.

Take prescribed vitamins as directed and for the appropriate time. If you have pernicious anemia, you must have vitamin B12 injections for the remainder of your life. Any chronic vitamin B12 deficiency requires lifelong treatment. If you are pregnant or breastfeeding, requirements may be greater; you usually may need additional vitamin supplements.

Keep appointments for follow-up visits and obtain the necessary laboratory tests.

Keep appointments for follow-up visits and obtain the necessary laboratory tests.

Vitamin C

Know about dietary sources of vitamin C. This vitamin occurs in citrus fruits and juices, red and green peppers, broccoli, cauliflower, brussels sprouts, cantaloupe, kiwi fruit, mustard greens, strawberries, and tomatoes.

Know about dietary sources of vitamin C. This vitamin occurs in citrus fruits and juices, red and green peppers, broccoli, cauliflower, brussels sprouts, cantaloupe, kiwi fruit, mustard greens, strawberries, and tomatoes.

Be aware that vitamin C improves the absorption of iron.

Be aware that vitamin C improves the absorption of iron.

Understand that vitamin C, which acidifies the urine, may alter the excretion of some drugs.

Understand that vitamin C, which acidifies the urine, may alter the excretion of some drugs.

VITAMIN E

The following discussion concerns vitamin E, or alphatocopherol.

Pharmacokinetics and Use

Vitamin E is absorbed from the GI tract if fat absorption is normal. It is primarily stored in adipose tissue. It is metabolized in the liver and eliminated primarily in bile.

The most important therapeutic use of vitamin E is for vitamin E replacement in the narrow, specific circumstances in which vitamin E deficiency occurs. Table 33.3 gives route and dosage information for vitamin E.

Adverse Effects and Contraindications

Large amounts of vitamin E are relatively nontoxic but can interfere with vitamin K action (blood clotting) by decreasing platelet aggregation and producing a risk of bleeding. Excessive doses can also cause fatigue, headache, blurred vision, nausea, and diarrhea. If signs or symptoms of vitamin E excess appear, it is essential to stop the intake of any known source of vitamin E.

Contraindications to vitamin E include a history of allergic reaction to vitamin E or hypervitaminosis E. Patients with a history of bleeding disorders or thrombocytopenia should not take vitamin E.

Nursing Implications

Preventing Interactions

Mineral oil and cholestyramine decrease the absorption of vitamin E, which means that vitamin E should not be administered at the same time as these substances. Also, this vitamin may increase the anticoagulant effect of warfarin. Vitamin E may increase the absorption, hepatic storage, and use of vitamin A.

Administering the Medication

People should take oral vitamin E preparations before meals on an empty stomach. However, to prevent nausea, people may also take them after food or meals.

Assessing for Therapeutic and Adverse Effects

The nurse observes for decreased signs and symptoms of vitamin E deficiency. In addition, the nurse checks for signs of hypervitaminosis E, including bleeding, fatigue, headache, blurred vision, nausea, and diarrhea.

Patient Teaching

Box 33.2 identifies patient teaching guidelines for vitamins, including vitamin E.

VITAMIN K

The following discussion concerns vitamin K, or phytonadione.

Pharmacokinetics and Use

After absorption, vitamin K is concentrated in the liver. Minimal amounts of the vitamin are stored. It crosses the placental barrier and enters breast milk. Onset of action after an oral dose is 6 to 12 hours and after a subcutaneous dose, 1 to 2 hours. Metabolism occurs rapidly in the liver, and elimination is in the bile and urine.

Vitamin K has two important therapeutic uses: (1) to correct hypoprothrombinemia caused by inadequate levels of vitamin K and (2) to reverse the effects of warfarin (Coumadin) overdose. Table 33.3 gives route and dosage information for vitamin K.

Adverse Effects and Contraindications

No symptoms have been observed from excessive intake of vitamin K. Mild adverse effects of vitamin K intake may include facial flushing, alterations in taste, or redness and pain at the injection site. The FDA has issued a BLACK BOX WARNING ♦ stating that IV administration of vitamin K may result in an anaphylactic type of reaction with risks of shock, cardiorespiratory arrest, and death, even with drug dilution and slow administration.

Contraindications to vitamin K include a history of allergic reaction as well as a history of allergic reaction to benzyl alcohol or castor oil.

Nursing Implications

Preventing Interactions

Mineral oil as well as cholestyramine and other bile acid sequestrants inhibit the absorption of vitamin K if taken at the same time. Increased vitamin K levels decrease the anticoagulant effect of warfarin. It is necessary to avoid the use of vitamin K as a drug when a patient is receiving warfarin, and significant increases or decreases in dietary vitamin K may necessitate adjustment of the warfarin dose.

Administering the Medication

Oral and subcutaneous routes for vitamin K administration are preferred. Both the IM route and the IV route are associated with severe hypersensitivity reactions. People may take the vitamin without regard to meals. They should avoid taking it at the same time as mineral oil or bile acid sequestrants.

It is necessary to protect all vitamin K preparations from light.

Assessing for Therapeutic and Adverse Effects

The nurse observes for decreased signs and symptoms of vitamin K deficiency. This includes decreased bleeding and more nearly normal blood coagulation tests.

Oral vitamin K rarely produces adverse reactions. Following subcutaneous injection, the nurse observes the injection site for redness and pain. Use of the IM and IV routes requires close observation for anaphylactic reaction as evidenced by chills, fever, diaphoresis, dyspnea, hypotension, bronchospasm, respiratory arrest, cardiac arrest, shock, and death. The means for emergency resuscitation must be immediately available.

Patient Teaching

Box 33.2 identifies patient teaching guidelines for vitamins, including vitamin K.

Water-Soluble Vitamins

VITAMIN B COMPLEX: VITAMIN B1, VITAMIN B3, AND VITAMIN B6

Most vitamin B complex deficiencies are multiple, rather than single, and treatment consists of administration of a multivitamin that contains several B complex vitamins. If a single deficiency seems predominant, that vitamin may be given alone or in addition to a multivitamin preparation. Three of the vitamin B complex vitamins are presented together in this section because they have much in common and are prototypical of the B complex vitamins as a whole: vitamin B1 (thiamine), vitamin B3 (niacin), and vitamin B6 (pyridoxine). Vitamin B12 (cyanocobalamin) and folic acid are discussed separately below because of their common use in the treatment of anemia.

Pharmacokinetics and Use

Thiamine, niacin, and pyridoxine are absorbed from the GI tract. Thiamine is widely distributed and enters breast milk. Niacin crossed the placenta and enters breast milk. Pyridoxine is stored in the liver and crosses the placental barrier. Niacin and pyridoxine are metabolized in the liver. Thiamine, niacin, and pyridoxine are eliminated by the kidneys in the urine.

Table 33.3 gives route and dosage information for the B complex vitamins.

Use in Patients With Renal or Hepatic Impairment

Both niacin and pyridoxine warrant caution in renal impairment. People with liver disease should not take niacin because it may increase liver enzymes and bilirubin and cause further liver damage. Long-acting dosage forms may be more hepatotoxic than the fast-acting forms.

Adverse Effects and Contraindications

• Thiamine: history of an allergic reaction to the vitamin

• Niacin: hepatic impairment, active peptic ulcer disease, arterial bleeding, and lactation. Caution is necessary with a history of jaundice, hepatobiliary disease, peptic ulcers, high alcohol consumption, renal impairment, unstable angina, gout glaucoma, and diabetes mellitus. Administration causes vasodilation, which may result in dizziness, hypotension, and injury from falls.

• Pyridoxine (IV form): cardiac disease. Caution is warranted with renal impairment.

Nursing Implications

Preventing Interactions

• Thiamine: no important drug interactions

• Niacin: increases the risk of rhabdomyolysis from the statin antihyperlipidemics, increases the effectiveness of antihypertensives and vasoactive drugs, and increases the risk of bleeding from anticoagulants. Bile acid sequestrants decrease absorption.

• Pyridoxine: accelerates the peripheral conversion of levodopa into dopamine, thus decreasing the amount of levodopa that is available to cross into the central nervous system (CNS). Isoniazid decreases the effect of pyridoxine.

Administering the Medication

• Thiamine: preferred route of administration is by mouth; people may take it without regard to food. It is necessary to swallow enteric-coated tablets whole, not chewed or crushed. The IM and IV routes are for severe deficiency states only.

• Niacin: people may take oral niacin, except for timed-release forms, with or after meals, which decreases anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and flatulence. They should swallow timed-release forms whole, not chewed or crushed. The nurse should instruct the patient to sit or lie down for about 30 minutes after administration because niacin causes vasodilation and possible dizziness and hypotension.

• Pyridoxine: the general route of administration is oral, and people should swallow sustained-release or enteric forms of pyridoxine whole, not chewed or crushed.

Assessing for Therapeutic Effects

The nurse assesses for decreased signs and symptoms of deficiency. With B complex vitamins, it is necessary to observe for decreased or absent stomatitis, glossitis, seborrheic dermatitis, neurologic problems (neuritis, convulsions, mental deterioration, psychotic symptoms), cardiovascular problems (edema, heart failure), and eye problems (itching, burning, photophobia). Deficiencies of B complex vitamins commonly occur together and produce many similar manifestations.

Assessing for Adverse Effects

Adverse reactions are generally unlikely to occur with B complex multivitamin preparations. They are most likely to develop with large IV doses and rapid administration. The observes for the following:

• Niacin and thiamine (parenteral): hypotension and anaphylactic shock

• Niacin (oral): anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and postural hypotension