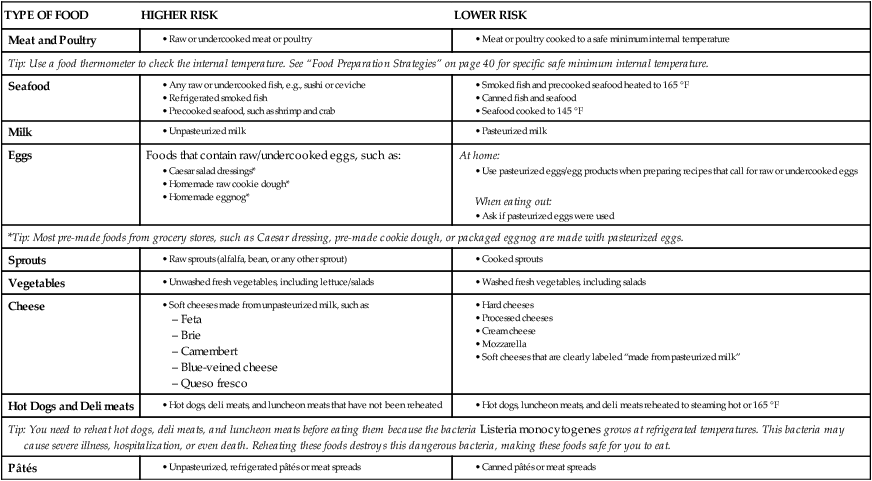

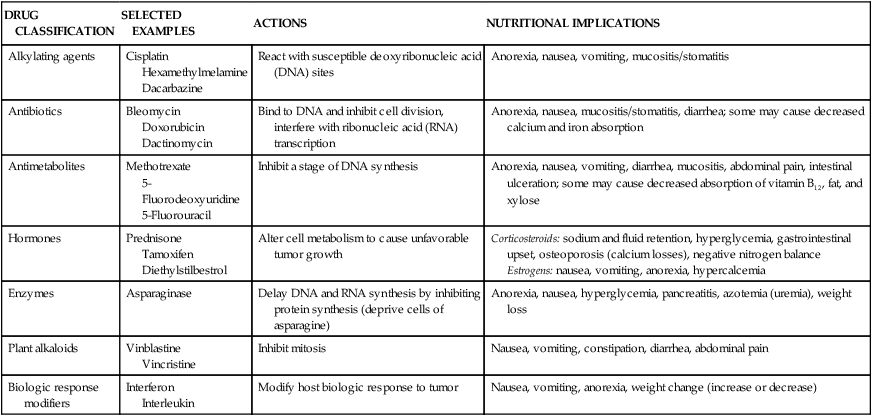

Cancer cells differ from normal cells in several ways. These characteristics may involve any or all of the following: (1) uncontrolled cellular reproduction occurs, in which cells become independent of normal growth signals; (2) cells contain abnormal nucleus and cytoplasm; and (3) the mitosis rate generally increases. The nucleus of the cells may be an abnormal shape and have clearly abnormal chromosomes. This process that results in abnormal cell production is called carcinogenesis.1 Cancer remains a leading cause of mortality in the United States; in 2008, there were an estimated 1.44 million new cases. Cancer is the second leading cause of death, with more than 550,000 deaths each year. Most diagnoses of cancer occur in older individuals, with almost two thirds in people older than age 65. The most common types of cancer include lung, prostate, breast, and colorectal (Box 22-1).2 Scientists estimate that 50% to 75% of all cancer deaths can be linked to human behaviors and lifestyle factors. Nutrition factors are considered one of the important environmental and lifestyle factors in the etiology and prevention of cancer.3 Nutrition and dietary factors may interact within the process of carcinogenesis in all three stages: initiation, promotion, and progression. Furthermore, nutritional factors may assist in blocking those three stages. For example, antioxidants in the diet may protect the cell from DNA mutation3 (see the Health Debate box, Fact or Fantasy? Food as Pharmaceuticals?). It is important to remember that no one food causes cancer and no one food can prevent it. The National Cancer Institute encourages cancer prevention by encouraging the following guidelines: • Not smoking cigarettes or using other tobacco products • Not drinking too much alcohol • Eating five or more daily servings of fruits and vegetables • Maintaining or reaching a healthy weight With more than 100 variations and as the second leading cause of death, cancer affects many individuals in the United States. The physiologic response to malignancy is different for each specific tumor type, but there are general nutrition risk factors that may apply to many cancer patients. Physical impairment because of the location of the tumor or the extent of tumor involvement, metabolic changes, and the use of antineoplastic therapy all place the patient with cancer at increased risk of developing malnutrition or the wasting syndrome of cancer: cachexia. Cancer cachexia is a complex syndrome that results in severe wasting of lean body mass and weight loss. Much research has attempted to establish an understanding of this syndrome. Cytokines are proteins that, in small amounts, assist in the communication between cells of the immune system. It is hypothesized that these cytokines, such as lipid mobilizing factor, interleukins, interferons, and proteolysis inducing factor, drive the altered metabolic response in cachexia. Weight loss, anorexia, hypermetabolism, wasting of skeletal muscle mass, and increased levels of lipid breakdown are the result. Cachexia affects almost 50% of all cancer patients and is present even at the beginning stages of tumor development before actual weight loss is observed. Aggressively approaching nutrition support as a major component of medical care can assist with minimizing the nutritional complications of cancer.4 Can adequate nutrition make a difference in those patients with cancer? The answer is yes. Maintenance of nutritional status may accomplish the following:4–6 Treatment for many malignancies (particularly, solid tumors) includes surgical resection of the tumor.1 This route of treatment can allow for diagnosis, resecting a solid tumor, preventing metastasis of the malignancy, or reducing the size of the tumor to alleviate pain. The nutritional consequences related to surgery are dependent on the type and extent of the surgical resection. Resections of any portion of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract can cause alterations in nutrition intake and nutrient absorption.6 Second, energy and protein requirements may need to be increased to promote optimal wound healing postoperatively. Malabsorption does tend to be the primary nutritional problem with surgeries involving the GI tract; yet unless small bowel resection is extensive, the adaptability of the small intestine may prevent the occurrence of major clinical problems.6 Many cancer patients enter surgery already experiencing protein-kcal malnutrition that places them at higher risk for complications. For example, more than 60% of patients with malignancies affecting the head and neck enter surgery malnourished.7 Additionally, any problems associated with surgery (Table 22-1) will be further complicated if the patient receives subsequent radiation therapy and chemotherapy. TABLE 22-1 NUTRITION SIDE EFFECTS OF CANCER SURGERY Data from McCallum PD, Polisena CG, editors: The clinical guide to oncology nutrition, Chicago, 2002, American Dietetic Association. Most chemotherapy protocols include a combination of chemotherapy agents. Chemotherapy agents include alkylating, antimetabolite agents (folate antagonists), purine/pyrimidine antagonists, anthracyclines, platinum antitumor compounds, antibiotics, nitrosoureas, mitotic inhibitors, cytokines, biologic response modifiers, monoclonal antibodies, immunotherapy, hormones, and enzymes. These agents act by inhibiting one or more steps of DNA synthesis in rapidly proliferating cells that are characteristic of the malignant cell or by enhancing the host’s immune system to allow for improved response to therapy. Using a combination of medications that interrupt the cancer process in different ways allows for maximum effect with the fewest side effects. Cells of the bone marrow and those lining the GI tract tend to be susceptible to damage from chemotherapy because of their rapid turnover rate.1,4,6 The effect on these cells accounts for many of the side effects associated with chemotherapy including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, mucositis, hair loss, and immunosuppression.6,7 The severity and manifestation of the side effects depend on the particular chemotherapy agent, dosage, duration of treatment, rates of metabolism, accompanying drugs, and individual tolerance. These symptoms can lead to malnutrition through a variety of mechanisms: anorexia; nausea; vomiting; mucositis; stomatitis; cardiac, renal, and liver injury (toxicity); and learned food aversions.4–7 Nutritional implications of chemotherapeutic agents are summarized in Table 22-2. TABLE 22-2 NUTRITIONAL IMPLICATIONS OF CHEMOTHERAPEUTIC AGENTS Data from McCallum PD, Polisena CG, editors: The clinical guide to oncology nutrition, Chicago, 2002, American Dietetic Association. Nutritional problems vary according to the region or area of the body radiated, dose, fractionation, and whether radiation is used as combination therapy with surgery or chemotherapy.4–7 Complications may develop during radiation treatment or become chronic and progress even after treatment is completed.4–7 Primary radiation sites that result in nutrition problems include the head and neck, the abdomen and pelvis (GI tract), and the central nervous system (CNS).4–7 Radiation at any of the three sites may cause anorexia, nausea, and vomiting. In the head and neck these common effects create problems of food ingestion, such as stomatitis, esophageal mucositis, loss of taste sensation, and changes in the production of saliva. Side effects to the abdomen and pelvis alter the GI tract (radiation enteritis), reducing digestion and absorption of nutrients because of the development of diarrhea and steatorrhea, and possibly, malabsorption, ulceration, and bowel damage or obstruction. Bone marrow transplantation (BMT) is used to treat certain hematologic malignancies (acute and chronic leukemia and some forms of lymphoma), as well as in adjunct therapy for solid tumors such as breast cancer.1 Types of transplant include autologous, allogeneic, and syngenic. When using bone marrow transplant as the treatment of a solid tumor, the patient’s own bone marrow is harvested and saved before the initiation of chemotherapy or radiation therapy. The patient then receives high-dose chemotherapy and possibly total body irradiation to eradicate the cancer.4–7 The patient’s own bone marrow is then infused as a “rescue” from the effects of both chemotherapy and radiation. For hematologic malignancies, a patient receives bone marrow from a genetically matched donor (allogeneic) or in some cases from a twin (syngenic). The ability to maintain adequate oral intake is difficult because of the nausea, vomiting, and mucositis that is associated with such high-dose therapies. Parenteral nutrition is a standard component of transplantation protocols, but when possible, recent research indicates that maintaining some oral intake or providing enteral nutrition is important to maintaining the integrity of the small intestine.8 Immunosuppression, as a result of the antineoplastic regimens and BMT, places the BMT patient at high risk for infections from bacterial and fungal pathogens. Pathogens can be commonly found in the environment, including fresh fruits and vegetables that ordinarily do not present a hazard to healthy persons (Box 22-2). Therefore, a low-bacterial diet is indicated whenever the plasma neutrophil (a type of white blood cell) count is less than 1000 mm3.6,7 Standard practice varies between institutions, but in general, food safety guidelines for patients with low immune function or who are neutropenic include avoiding undercooked meats and eggs, ensuring that raw fruits and vegetables are washed well and/or are peeled (including salads and garnishes), and following appropriate sanitation guidelines for food preparation and storage. Frequent monitoring of nutritional intake and encouragement to take in adequate nutrition are essential in the care of these patients (Box 22-3).

Nutrition in Cancer, AIDS, and Other Special Problems

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grodner/foundations/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grodner/foundations/ ![]() Nutrition Concepts Online

Nutrition Concepts Online

Cancer

![]() The rate of tumor growth is dependent on characteristics of both the host and tumor. Host factors may include age, sex, nutritional status, the presence of other diseases, hormone production, and immune function. Tumor factors could include where the tumor is located and its access to adequate blood supply.1

The rate of tumor growth is dependent on characteristics of both the host and tumor. Host factors may include age, sex, nutritional status, the presence of other diseases, hormone production, and immune function. Tumor factors could include where the tumor is located and its access to adequate blood supply.1

Nutrition and the Diagnosis of Cancer

Benefits of Nutritional Adequacy

Nutritional Effects of Cancer Treatments

Surgery

SITE OF SURGERY

SIDE EFFECT

Head and neck

Impaired chewing and swallowing

Esophagectomy

Diarrhea, steatorrhea, esophageal stenosis

Vagotomy

Gastric stasis, diarrhea, fat malabsorption

Gastrectomy

Dumping syndrome; hypoglycemia; malabsorption; possible deficiencies of iron, calcium, vitamin B12, and fat-soluble vitamins

Pancreatectomy

Type 1 diabetes mellitus, possible malabsorption of fats, protein, fat-soluble vitamins, minerals

Small bowel resection

Possible malabsorption of many nutrients; depends on extent and site of surgery

Ileostomy

Sodium and water losses, vitamin B12, malabsorption, fat malabsorption, bile salt diarrhea

Chemotherapy

DRUG CLASSIFICATION

SELECTED EXAMPLES

ACTIONS

NUTRITIONAL IMPLICATIONS

Alkylating agents

Cisplatin

Hexamethylmelamine

Dacarbazine

React with susceptible deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) sites

Anorexia, nausea, vomiting, mucositis/stomatitis

Antibiotics

Bleomycin

Doxorubicin

Dactinomycin

Bind to DNA and inhibit cell division, interfere with ribonucleic acid (RNA) transcription

Anorexia, nausea, mucositis/stomatitis, diarrhea; some may cause decreased calcium and iron absorption

Antimetabolites

Methotrexate

5-Fluorodeoxyuridine

5-Fluorouracil

Inhibit a stage of DNA synthesis

Anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, mucositis, abdominal pain, intestinal ulceration; some may cause decreased absorption of vitamin B12, fat, and xylose

Hormones

Prednisone

Tamoxifen

Diethylstilbestrol

Alter cell metabolism to cause unfavorable tumor growth

Corticosteroids: sodium and fluid retention, hyperglycemia, gastrointestinal upset, osteoporosis (calcium losses), negative nitrogen balance

Estrogens: nausea, vomiting, anorexia, hypercalcemia

Enzymes

Asparaginase

Delay DNA and RNA synthesis by inhibiting protein synthesis (deprive cells of asparagine)

Anorexia, nausea, hyperglycemia, pancreatitis, azotemia (uremia), weight loss

Plant alkaloids

Vinblastine

Vincristine

Inhibit mitosis

Nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea, abdominal pain

Biologic response modifiers

Interferon

Interleukin

Modify host biologic response to tumor

Nausea, vomiting, anorexia, weight change (increase or decrease)

Radiation Therapy

Bone Marrow Transplantation

Nutrition in Cancer, AIDS, and Other Special Problems

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access