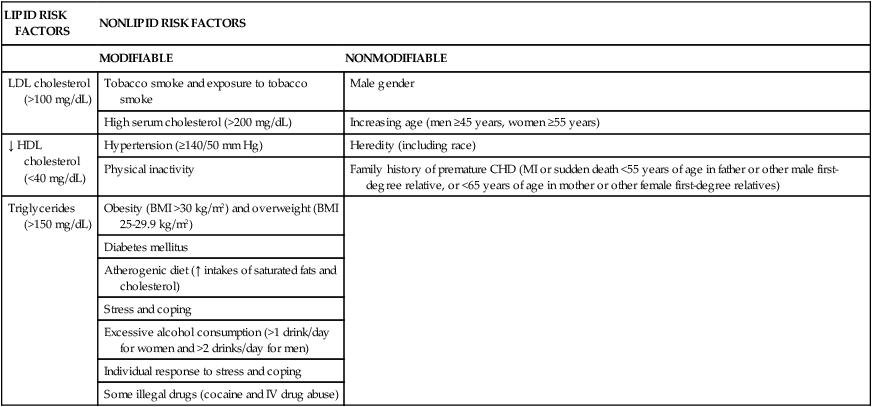

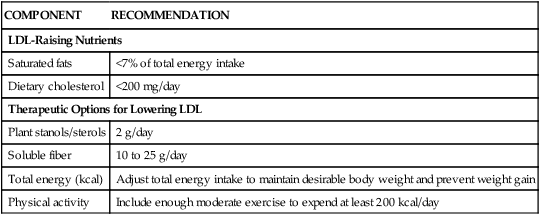

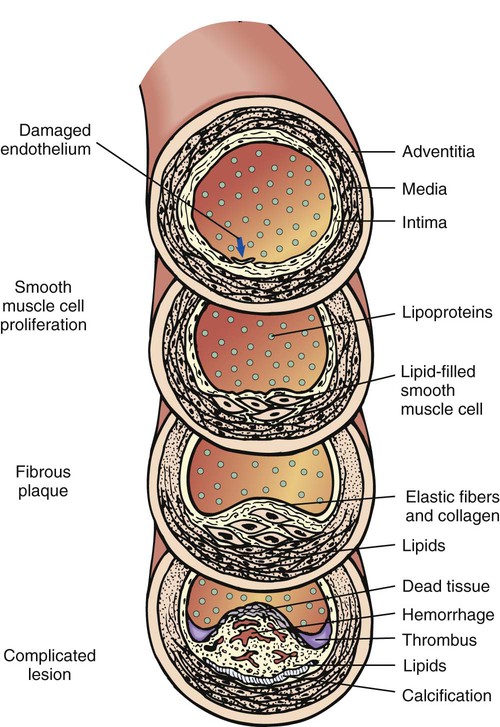

The term cardiovascular disease (CVD) encompasses a group of diseases and conditions that affect the heart and blood vessels: coronary artery disease (CAD) (also called coronary heart disease [CHD]), hypertension (HTN), peripheral vascular disease (PVD), congestive heart failure (CHF), and congenital heart diseases. CVD has been a public health issue since 1900 and is currently the leading cause of death in the United States for both men and women in all ethnic and racial groups. While death rates from CVD have declined, the burden of the disease remains high. More than 2300 lives are claimed each day by CVD—an average of 1 death every 38 seconds. Cardiovascular disease kills more Americans each year than the next four leading causes of death combined.1 Most people who have heart attacks die before they ever reach a hospital for treatment, a situation that emphasizes the need for prevention of heart disease. Several risk factors for cardiovascular disease are modifiable or altogether preventable; nonetheless, more than 80% of adult Americans have at least one major risk factor.2 Risk factors are categorized into two groups: modifiable and nonmodifiable (Table 20-1). TABLE 20-1 MAJOR RISK FACTORS IN CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE Data from Banasik JL: Alterations in cardiac function. In Copstead LC, Banasik JL, eds: Pathophysiology, ed 3, St. Louis, 2005, Saunders; American Heart Association: Heart and stroke facts, Dallas, 1992-2003, Author. Accessed April 7, 2010, from www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=3000333; Grundy SM, et al: Primary prevention of coronary heart disease: guidance from Framingham, Circulation 97:1876-1887, 1998; National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP): Third report of the NCEP expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III): executive summary, NIH Pub No 01-3670, Washington, DC, 2001 (May), National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP): Third report of the NCEP expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III), Washington, DC, 2001, National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The underlying pathologic process responsible for coronary artery disease (CAD) is atherosclerosis (Figure 20-1). Beginning in childhood, atherosclerosis may gradually lead to arteriosclerosis.3 The most common and serious manifestation of atherosclerosis is development of lesions in coronary arteries that can cause angina pectoris if blood flow is partially occluded by a thrombus. If blood flow to the heart is completely occluded, then a myocardial infarction occurs. If thrombosis occurs in a cerebral artery, a cerebrovascular accident (CVA) or stroke occurs. PVD occurs when atherosclerosis in the abdominal aorta, iliac arteries, and femoral arteries produces temporary insufficient blood flow in the arteries on exertion (intermittent claudication) or ischemic necrosis of the extremities, which may lead to gangrene.4 The most frequent approach in assessing CAD risk is to measure cholesterol and proportions of the different types of plasma lipoproteins that carry cholesterol in the blood. Cholesterol is a not actually a lipid, but it travels in the bloodstream in spherical particles called lipoproteins, which contain lipids and proteins. Cholesterol is an essential component of cell membranes and a precursor of bile acids and steroid hormones and is not required in the diet after weaning. Plasma lipid profile is commonly measured by analyzing the three major classes of lipoproteins in blood from a fasting individual: very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL), low-density lipoproteins (LDL), and high-density lipoproteins (HDL). LDL cholesterol contains approximately 60% to 70% of total serum cholesterol (TC), and high serum levels are causally related to increased risk of CAD. HDLs usually contain 20% to 30% of the total cholesterol, and serum levels are inversely correlated with risk for CAD. VLDLs are largely composed of triglyceride, which contains 10% to 15% of the TC5 (Box 20-1). The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III) report6 emphasizes LDL cholesterol as the primary target for cholesterol-lowering therapy. The report cites research from laboratory investigations, epidemiologic research, and clinical trials that robustly show LDL-lowering therapy reduces risk for CHD. Therefore, primary goals of therapy are stated in terms of LDL cholesterol (Box 20-2). Another risk factor for CHD is elevated triglyceride levels.5,6 Triglyceride is the most common type of fat found in the body. The body gets triglyceride directly from foods and makes it in the liver from carbohydrates, alcohol, and some cholesterol. Serum triglyceride levels range from about 50 to 250 mg/dL.7 Several factors that may cause triglyceride levels to be elevated are as follows: • Very high carbohydrate intake (>60% of total energy) • Other diseases (e.g., type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure, nephrotic syndrome) • Certain drugs (e.g., corticosteroids, protease inhibitors for human immunodeficiency virus [HIV], beta-adrenergic blocking agents, estrogens) After evaluating available research, the ATP III panel concluded that the association between serum triglyceride and CHD is stronger than previously recognized and it considers elevated serum levels as a factor to identify people at risk who are in need of intervention for risk reduction.5,6 Classifications of triglyceride levels are outlined in Table 20-2. TABLE 20-2 CLASSIFICATION OF SERUM TRIGLYCERIDES From National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP): Third report of the NCEP expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III), Washington, DC, 2001, National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The ATP III report cites convincing epidemiologic evidence identifying HDL cholesterol as a strong independent and inverse risk factor for increased CHD morbidity and mortality.6 Low HDL cholesterol is defined as a level of less than 40 mg/dL in both men and women.6 Factors contributing to low HDL cholesterol levels include the following: • Elevated serum triglyceride levels • Very high carbohydrate intake (>60% of total energy) • Certain drugs (e.g., beta blockers, anabolic steroids, progestational agents) Often, a common form of dyslipidemia (atherogenic dyslipidemia) characterized by three lipid abnormalities (elevated triglycerides, small LDL particles, and low HDL cholesterol) is seen in people with premature CHD.6 Characteristics of individuals with atherogenic dyslipidemia are obesity, abdominal obesity, insulin resistance, and physical inactivity.8 Because each component of atherogenic dyslipidemia is individually atherogenic, the combination is considered an independent risk factor.6 Lifestyle modification—weight control and increased physical activity—is the treatment of choice6 (see the Cultural Considerations box, Using T’ai Chi to Reduce Cardiovascular Risk Factors). Several nonlipid risk factors are associated with increased CHD risk and are targets for intervention in preventive efforts. Fixed risk factors (increasing age, male gender, and family history of premature CHD) cannot be modified, and their existence implies need for intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol.6 Modifiable nonlipid risk factors include hypertension, cigarette smoking, diabetes, obesity, physical inactivity, and atherogenic diet. Table 20-1 summarizes CHD risk factors other than elevated LDL cholesterol. The ATP III report5,6 recommends a comprehensive lifestyle approach to reducing risk for CHD called Therapeutic Lifestyle Changes (TLC), which incorporates the following components:5,6 • Reduced intake of saturated fats and cholesterol • Therapeutic dietary options to enhance lowering of LDL (e.g., plant stanols/sterols and increased soluble fiber) Components of TLC are outlined in Table 20-3. ATP III also suggests ranges for other macronutrients in the TLC diet (Table 20-4). Overall, composition of the TLC diet is consistent with recommendations of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (see Chapter 2). Box 20-3 outlines the ATP III’s TLC recommendations. TABLE 20-3 ESSENTIAL COMPONENTS OF THERAPEUTIC LIFESTYLE CHANGES (TLC) Data from National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP): Third report of the NCEP expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III), Washington, DC, 2001, National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. TABLE 20-4 NUTRIENT COMPOSITION OF THE THERAPEUTIC LIFESTYLE CHANGES (TLC) DIET *ATP III allows for increase of total fat to 35% total energy intake and reduction in carbohydrate to 50% for people with the metabolic syndrome. Any increase in fat intake should be in the form of either polyunsaturated or monounsaturated fat. †Carbohydrates should come primarily from foods rich in complex carbohydrates including grains—especially whole grains—fruits, and vegetables. Data from National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP): Third report of the NCEP expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III): executive summary, NIH Pub No 01-3670, Washington, DC, 2001 (May), National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP): Third report of the NCEP expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III), Washington, DC, 2001, National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Reducing saturated fat (<7% of total energy intake) and cholesterol (<200 mg/day) in the diet is the foundation of the TLC diet.6 The strongest nutritional influence on serum LDL cholesterol levels is saturated fats. Moreover, there is a “dose response relationship” between saturated fats and LDL cholesterol levels.6 For every 1% increase in kcal from saturated fats as a percent of total energy, serum LDL cholesterol increases roughly 2%. Conversely, a 1% decrease in saturated fats will lower serum cholesterol by about 2%.8 Although weight reduction by itself, even of a few pounds, will reduce LDL cholesterol levels,6 weight reduction achieved using a kcal-controlled diet low in saturated fats and cholesterol will enhance and maintain LDL cholesterol reductions.6,8 Although dietary cholesterol does not have the equivalent impact of saturated fat on serum LDL cholesterol levels,6 high cholesterol intakes increase LDL cholesterol levels.6,9 Therefore, reducing dietary cholesterol to less than 200 mg per day decreases serum LDL cholesterol in most people.6 Substitution of monounsaturated fat for saturated fats at an intake level of up to 20% of total energy intake is recommended on the TLC diet.6 Monounsaturated fats lower LDL cholesterol levels relative to saturated fats6 without decreasing HDL cholesterol or triglyceride levels.6,11 The best sources of monounsaturated fats are plant oils and nuts.6 (See Box 5-1 for a listing of plant oils and nuts.) When used instead of saturated fats, polyunsaturated fats, in particular linoleic acid, reduce LDL cholesterol levels. On the other hand they can also bring about small reductions in HDL cholesterol when compared side by side with monounsaturated fats.6 Liquid vegetables oils, semiliquid margarines, and other margarines low in trans fatty acids are recommended by the TLC diet as the best sources of polyunsaturated fats. Recommended intakes can range up to 10% of total energy intake.6 Saturated fats and trans fatty acids increase LDL cholesterol levels,10 whereas serum levels of LDL cholesterol do not appear to be affected by total fat intake.6 For that reason, the ATP III suggests it is not essential to limit total fat intake for the particular goal of reducing LDL cholesterol levels, provided saturated fats are decreased to goal levels.6 When saturated fats are replaced with carbohydrates, LDL cholesterol decreases. Then again, very high intakes of carbohydrates (>60% total energy intake) are associated with a reduction in HDL cholesterol and increase in serum triglyceride.6,11,12 Increasing soluble fiber intake can sometimes reduce these responses.6 Generally, increasing soluble fiber to 5 to 10 g per day is accompanied by a roughly 5% reduction in LDL cholesterol.13 Although dietary protein, as a rule, has a negligible effect on serum LDL cholesterol level, substituting plant-based proteins for animal proteins appears to decrease LDL cholesterol.6 This may be caused by the lack of cholesterol and lower saturated fat content of plant-based protein foods (e.g., legumes, dry beans, nuts, whole grains, and vegetables). This is not to say all animal proteins are high in saturated fat and cholesterol. Fat-free and low-fat dairy products, egg whites, fish, skinless poultry, and lean cuts of beef and pork are low in saturated fat and cholesterol. All foods of animal origin contain cholesterol. When 5 to 10 g of soluble fiber (e.g., oats, barley, psyllium, pectin-rich fruit, and beans) is added to the daily diet, there is a roughly 5% reduction in LDL cholesterol.13 This is considered a therapeutic alternative to augment reduction of LDL cholesterol.6 Daily intakes of 2 to 3 g plant sterol/sterol esters (isolated from soybean and tall pine tree oils) present an additional therapeutic option because they have been shown to lower LDL cholesterol by 6% to 15%.6,14–16 The ATP III6 recommends patients at risk for CHD or with CHD be referred to registered dietitians or other qualified nutritionists for all stages of medical nutrition therapy. LDL cholesterol should be measured at 6-week intervals to evaluate response to TLC. If the LDL cholesterol target has been realized, or if improvement in LDL lowering has occurred, medical nutrition therapy should be continued. If the goal has not been achieved, several alternatives are available. First, medical nutrition therapy can be reexplained and reinforced. Next, therapeutic dietary options (outlined earlier) can be integrated into TLC. Response to nutrition therapy should be assessed in another 6 weeks. Achievement of the LDL cholesterol target indicates current intensity of medical nutrition therapy should be continued indefinitely. Thought should be given to continuing medical nutrition therapy before adding LDL-lowering medications. If it seems unlikely the LDL target will be realized with medical nutrition therapy, medications should be considered.6 Use of TLC will attain the LDL cholesterol target goal for many; LDL-lowering medications will be necessary for a segment of the population to achieve the prescribed goal for LDL cholesterol.6 If treatment with TLC alone is unsuccessful after 3 months, the ATP III recommends initiation of drug treatment. Use of LDL-lowering medications does not negate continued use or need for medical nutrition therapy. Nutrition therapy affords further CHD risk reduction beyond drug efficacy. Suggestions for combined use of TLC and LDL-lowering medications include the following:6 • Intensive LDL lowering with TLC, including therapeutic dietary options • Weight control plus increased physical activity

Nutrition for Cardiovascular and Respiratory Diseases

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grodner/foundations/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grodner/foundations/ ![]() Nutrition Concepts Online

Nutrition Concepts Online

Role in Wellness

LIPID RISK FACTORS

NONLIPID RISK FACTORS

MODIFIABLE

NONMODIFIABLE

LDL cholesterol (>100 mg/dL)

Tobacco smoke and exposure to tobacco smoke

Male gender

High serum cholesterol (>200 mg/dL)

Increasing age (men ≥45 years, women ≥55 years)

↓ HDL cholesterol (<40 mg/dL)

Hypertension (≥140/50 mm Hg)

Heredity (including race)

Physical inactivity

Family history of premature CHD (MI or sudden death <55 years of age in father or other male first-degree relative, or <65 years of age in mother or other female first-degree relatives)

Triglycerides (>150 mg/dL)

Obesity (BMI >30 kg/m2) and overweight (BMI 25-29.9 kg/m2)

Diabetes mellitus

Atherogenic diet (↑ intakes of saturated fats and cholesterol)

Stress and coping

Excessive alcohol consumption (>1 drink/day for women and >2 drinks/day for men)

Individual response to stress and coping

Some illegal drugs (cocaine and IV drug abuse)

Coronary Artery Disease

TRIGLYCERIDE CATEGORY

ATP III LEVELS

Normal

<150 mg/dL

Borderline high

150 to 199 mg/dL

High

200 to 499 mg/dL

Very high

≥500 mg/dL

![]() Nonlipid Risk Factors

Nonlipid Risk Factors

Nutrition Therapy

COMPONENT

RECOMMENDATION

LDL-Raising Nutrients

Saturated fats

<7% of total energy intake

Dietary cholesterol

<200 mg/day

Therapeutic Options for Lowering LDL

Plant stanols/sterols

2 g/day

Soluble fiber

10 to 25 g/day

Total energy (kcal)

Adjust total energy intake to maintain desirable body weight and prevent weight gain

Physical activity

Include enough moderate exercise to expend at least 200 kcal/day

COMPONENT

RECOMMENDATION

Polyunsaturated fat

Up to 10% total energy intake

Monounsaturated fat

Up to 20% total energy intake

Total fat

25% to 35% total energy intake*

Carbohydrate†

50% to 60% total energy intake

Dietary fiber

20 to 30 g/day

Protein

Approximately 15% total energy intake

Components and Application of the Therapeutic Lifestyle Changes (TLC) Diet

Saturated fat and cholesterol

Monounsaturated fat

Polyunsaturated fats

Total fat

Carbohydrate

Protein

Further dietary options to reduce LDL cholesterol

Drug Therapy

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

, 1% milk, buttermilk, yogurt, cottage cheese, fat-free and low-fat cheese

, 1% milk, buttermilk, yogurt, cottage cheese, fat-free and low-fat cheese to 1 pound per week

to 1 pound per week