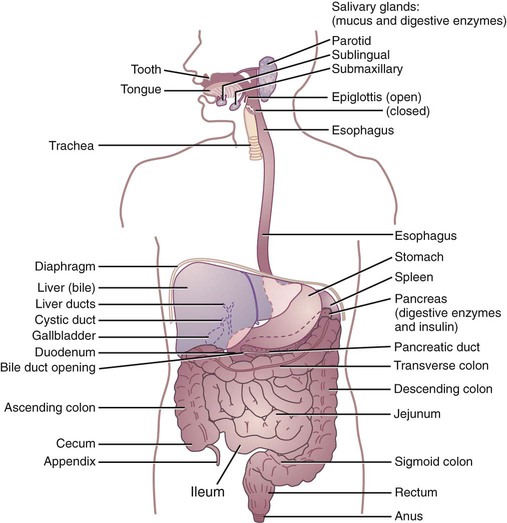

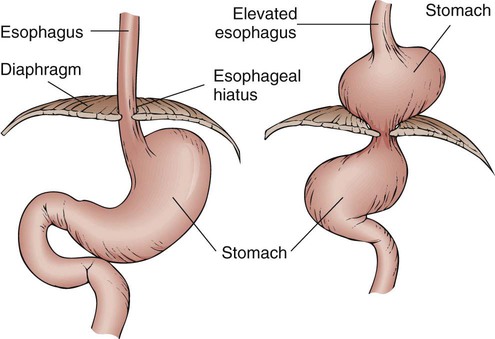

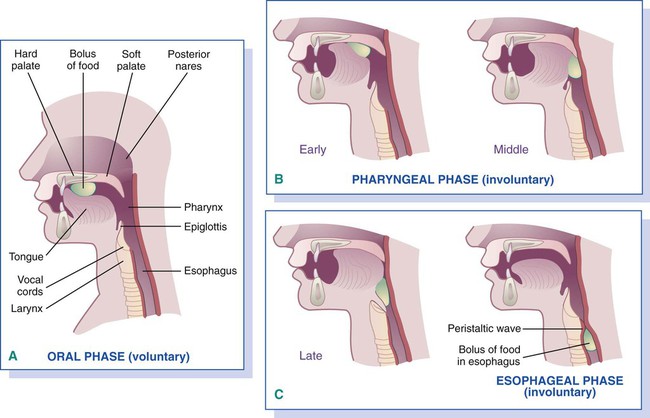

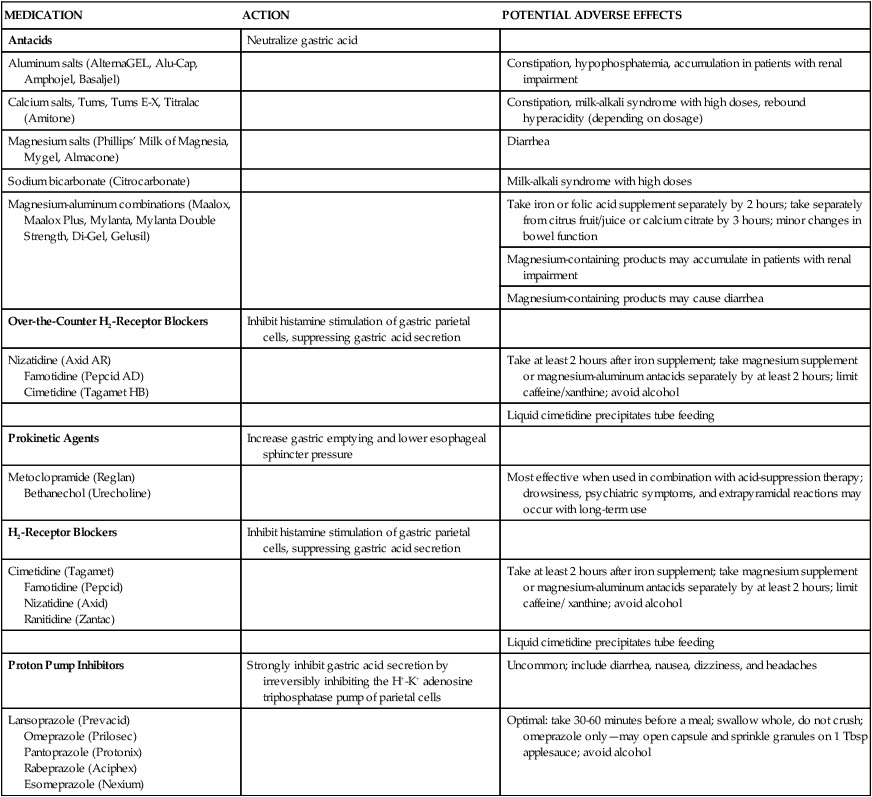

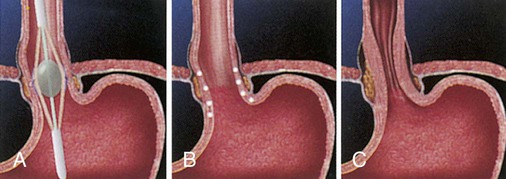

Almost everyone experiences intermittent gastrointestinal (GI) complaints from time to time. Indigestion, gas, bloating, nausea, abdominal pain or cramping, diarrhea, and esophageal reflux are some of the symptoms occasionally experienced by healthy people. Many GI disorders produce significant nutritional implications, and in many situations diet is the cornerstone of therapy for GI complaints. Evaluation of a patient’s GI symptoms requires a team effort to separate GI symptoms associated with dietary practices from those associated with GI disease or dysfunction. The registered dietitian’s role is to help identify unusual dietary practices, nutritional inadequacies, or food intolerances through the use of an in-depth diet history.1 The simple act of eating an apple may no longer be easy for individuals with disorders of the GI tract. The ability to chew, swallow, digest, and absorb nutrients, while passing fiber and other substances on for elimination, may be compromised by disorders of the GI tract (Figure 17-1). These disorders affect provision of nutrients to all other organs and systems of the body, thereby influencing overall health. The main focus of medical nutrition therapy for dysphagia is to provide nutrition in a form that fits specific anatomic and functional needs of the patient while maintaining or improving nutritional status and avoiding aspiration.2 For patients with chewing or swallowing difficulties, diets must be devised to meet nutritional needs and prevent aspiration. Patients may also experience changes in consistency tolerance. Thickening agents provide varying levels of consistency to accommodate individual needs because thin liquids are usually more difficult to swallow. We rarely think about swallowing, just as we don’t think about breathing or our heart beating. Swallowing takes place in three stages, as outlined in Figure 17-2: oral preparation and transit, pharyngeal transit, and esophageal transit. A disorder affecting any of these stages may require medical nutrition therapy. Patients sometimes give warning signs, including the following that they are at risk for swallowing problems:2 • Collecting food under the tongue, in the cheeks, or on the hard palate • Spitting food out of the mouth, or tongue thrusting • Decreasing oral transit time • Experiencing delay or absence of elevation of larynx while swallowing • Coughing before or after swallowing • Experiencing gargled voice after eating or drinking • Regurgitating food or liquid through nose, mouth, or tracheostomy tube • Not taking in adequate amounts of food or fluids, resulting in weight loss • Increasing time required to eat • Resisting food, such as clenching teeth, pushing food away, clutching throat Box 17-1 presents conditions that may cause dysphagia. No two patients with dysphagia are alike. Therefore, diet must be individualized based on the swallowing ability of the patient and, of course, the patient’s personal food preferences. Solid foods and liquids should be evaluated separately and modified based on texture, cohesiveness, density, viscosity, consistency, temperature, and taste. A nutritionally adequate diet for dysphagia involves considering these characteristics, along with careful planning to ensure nutritional adequacy. A three-stage dysphagia diet is outlined in Table 17-1. TABLE 17-1 Data from American Dietetic Association: Nutrition care manual, Chicago, 2009, Author. Accessed February 28, 2010, from www.nutritioncaremanual.org. When caring for patients with dysphagia, several aspects are of concern: bolus consistency, patient positioning, feeding rate, and specific swallowing techniques. Video-fluoroscopy swallow study (VFSS) determines the level of bolus consistency the patient can tolerate. Different physiologic problems dictate the necessity for different consistencies of food. For example, the most common swallowing disorder in older adults who have experienced stroke is a delayed or absent pharyngeal swallow.3 Patients with this type of disorder need puréed foods to provide stimulation that provokes the reflex to swallow. If the pharyngeal swallow is reduced (but not delayed or absent), liquids tend to be the most difficult consistency for patients. Thickening agents can be used to acquire the appropriate consistency. For patients who have lost coordination of the upper esophageal sphincter (cricopharyngeal dysfunction), thin liquids are the most appropriate (see the Personal Perspectives box, The Pain of Parkinson’s Disease).4 One of the safest eating positions for patients who have trouble swallowing is upright. If patients cannot sit up by themselves, the head of the bed should be raised to provide support, and pillows and wedges should be used to support arms, head, neck, or trunk when necessary. The upright position allows gravity to assist with the passage of food along the esophagus and helps prevent choking and aspiration.2 Enlisting the aid of a speech therapist is usually necessary to teach the patient various techniques to compensate for swallowing problems. Techniques include the supra glottic swallow and the Mendelson maneuver. The supraglottic swallow is appropriate for patients with reduced laryngeal function. This method requires teaching the patient to take a breath before swallowing, consciously hold the breath during the swallow, exhale forcefully or cough gently after the swallow, and swallow again to clear the mouth. The Mendelson maneuver is helpful for individuals with cricopharyngeal dysfunction. The patient is taught to elevate the larynx voluntarily to the maximum level during a swallow to allow food to pass. When lubrication is a problem, nursing personnel can also use several techniques to assist the patient. Encouraging the patient to think or talk about food before mealtime can help stimulate the flow of saliva, which aids in the formation of a bolus and the chewing and swallowing process. Tart or sour foods can stimulate saliva production. Having the patient lick jelly from the lips, pucker them, hum, or whistle helps strengthen mouth muscles, which may help the patient, learn to close the lips around a fork or spoon.5 Feeding patients with swallowing difficulty is usually the responsibility of nursing personnel. The following safe procedures are recommended:2,6 1. Position patient upright, bent slightly forward, with the chin tucked and head tilted forward. 2. Eliminate distractions so the patient can focus all attention on the meal. 3. The person feeding should sit at or below patient’s eye level while feeding. 4. Avoid asking patient to talk while eating. 5. Instruct the patient not to use liquids to clear the mouth of foods; in fact, they should be used only after the patient has cleared the food from the mouth. Encourage frequent dry swallows or coughing to help clear food from the mouth between bites. 6. Encourage small bites ( 7. Allow adequate time to feed. 8. Use spoons rather than cups because patients have less difficulty taking food and liquid this way. 9. While patient eats, check for voice quality. A wet or gurgled voice indicates food may be resting on the vocal cords. During the early stages of feeding, nursing supervision is necessary at meals to prevent or minimize swallowing problems. Patients should be reevaluated regularly to determine whether any changes need to be made in the consistency of fluids or food. Evaluating and documenting the patient’s food intake are also prudent to ensure adequate nutritional intake and status. If the patient’s nutritional needs are not or cannot be met orally, alternative methods should be considered.7 Normally, the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) prevents stomach contents from entering the esophagus, but various factors often decrease sphincter pressure (Box 17-2 and Figure 17-3). Unlike gastric mucosa, esophageal mucosa can be damaged when exposed to gastric contents. If not treated, GERD can result in esophagitis (inflammation of the lower esophagus). The reflux is thought to be aggravated by reclining after eating, stress, and increased intraabdominal pressure. Increased intraabdominal pressure can occur with coughing, straining, bending, vomiting, obesity, pregnancy, trauma, ascites, tightly fitting clothing around the waist, lifting heavy objects, and exercising strenuously.2 Older patients often experience respiratory symptoms of GERD, such as pneumonitis, chronic bronchitis, or asthma. GERD is treated medically by reducing intraabdominal pressure and gastric acid production. Medical management can be divided into six stages (Box 17-3 and Figure 17-4). Stages 1 to 4 entail medical management, and stage 5 involves surgical intervention.8 Table 17-2 summarizes medications that may be used to treat GERD, as well as their actions. Attention to medical metabolism of these medications and their interaction with other prescribed and over-the-counter medications should be considered, particularly among minority populations (see the Cultural Considerations box, Biologic Variations of Medication Metabolism). TABLE 17-2 MEDICATIONS USED TO TREAT GASTROESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE Data from Pronsky ZM, Crowe JP: Food-medication interactions, ed 16, Birchrunville, Pa, 2010, Food-Medication Interactions; National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse (NDDIC), National Institute of Diabetes & Digestive & Kidney Diseases (NIDDK): Heartburn, gastroesophageal reflux (GER), and gastrointestinal reflux disease (GERD), NIH Pub. No 07-0882, Bethesda, Md, 2007 (May), National Institutes of Health. Accessed February 28, 2010, from http://digestive.niddk.nih.gov/ddiseases/pubs/gerd/index.htm.

Nutrition for Disorders of the Gastrointestinal Tract

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grodner/foundations/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grodner/foundations/ ![]() Nutrition Concepts Online

Nutrition Concepts Online

Role in Wellness

Dysphagia

![]() Nutrition Therapy

Nutrition Therapy

LEVEL

RATIONALE

DESCRIPTION

Level 1: Puréed

Suitable for people with severely reduced oral preparatory stage abilities, impaired lip and tongue control, delayed swallow reflex triggering, oral hypersensitivity, reduced pharyngeal peristalsis, and/or cricopharyngeal dysfunction.

Thick homogeneous textures are emphasized. Puréed foods should be “spoon-thick” or “pudding-like” consistency. No coarse textures, nuts, raw fruits, or raw vegetables allowed. Liquid or crushed medications (refer to physician or pharmacist for pharmoefficacy of medications) are required and may be mixed with puréed fruits. Liquids and water are thickened with commercial thickening agent as needed to recommended consistency.

Level 2: Mechanically altered

Intended for patients who can tolerate a minimum amount of easily chewed foods. May be suitable for people with moderately impaired oral preparatory stage abilities, edentulous oral cavity, decreased pharyngeal peristalsis, and/or cricopharyngeal muscle dysfunction.

No coarse textures, nuts, raw fruits (except ripe or mashed bananas), or vegetables, except as noted. Puréed or slurried bread, if necessary. Liquid or crushed medications may still be required (refer to physician or pharmacist for pharmo-efficacy of medications). Liquids and water thickened as needed with commercial thickening agent to recommended consistency.

Level 3: Advanced

Designed for patients who chew soft textures. Based on a soft diet; may be appropriate for individuals with mild oral preparatory–stage deficits.

Textures are soft with no tough skins, no nuts or dry, crispy, raw, or stringy foods. Meats should be moist and tender or casseroles with small chunks of meat allowed. Fluid consistency ordered separately: may be thin, nectar-thick, honey-like, or spoon-thick. Moist potatoes, rice, and dressing allowed. All soups except those with tough meat or vegetables. Soft, peeled fruit without seeds. Moist breads and cereals allowed. All fats except those with chunky additives.

to 1 teaspoon solid food or about 10 to 15 mL liquid), especially if patient’s ability to manage food is impaired.

to 1 teaspoon solid food or about 10 to 15 mL liquid), especially if patient’s ability to manage food is impaired.

![]() Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease, Hiatal Hernia, and Esophagitis

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease, Hiatal Hernia, and Esophagitis

MEDICATION

ACTION

POTENTIAL ADVERSE EFFECTS

Antacids

Neutralize gastric acid

Aluminum salts (AlternaGEL, Alu-Cap, Amphojel, Basaljel)

Constipation, hypophosphatemia, accumulation in patients with renal impairment

Calcium salts, Tums, Tums E-X, Titralac (Amitone)

Constipation, milk-alkali syndrome with high doses, rebound hyperacidity (depending on dosage)

Magnesium salts (Phillips’ Milk of Magnesia, Mygel, Almacone)

Diarrhea

Sodium bicarbonate (Citrocarbonate)

Milk-alkali syndrome with high doses

Magnesium-aluminum combinations (Maalox, Maalox Plus, Mylanta, Mylanta Double Strength, Di-Gel, Gelusil)

Take iron or folic acid supplement separately by 2 hours; take separately from citrus fruit/juice or calcium citrate by 3 hours; minor changes in bowel function

Magnesium-containing products may accumulate in patients with renal impairment

Magnesium-containing products may cause diarrhea

Over-the-Counter H2-Receptor Blockers

Inhibit histamine stimulation of gastric parietal cells, suppressing gastric acid secretion

Nizatidine (Axid AR)

Famotidine (Pepcid AD)

Cimetidine (Tagamet HB)

Take at least 2 hours after iron supplement; take magnesium supplement or magnesium-aluminum antacids separately by at least 2 hours; limit caffeine/xanthine; avoid alcohol

Liquid cimetidine precipitates tube feeding

Prokinetic Agents

Increase gastric emptying and lower esophageal sphincter pressure

Metoclopramide (Reglan)

Bethanechol (Urecholine)

Most effective when used in combination with acid-suppression therapy; drowsiness, psychiatric symptoms, and extrapyramidal reactions may occur with long-term use

H2-Receptor Blockers

Inhibit histamine stimulation of gastric parietal cells, suppressing gastric acid secretion

Cimetidine (Tagamet)

Famotidine (Pepcid)

Nizatidine (Axid)

Ranitidine (Zantac)

Take at least 2 hours after iron supplement; take magnesium supplement or magnesium-aluminum antacids separately by at least 2 hours; limit caffeine/ xanthine; avoid alcohol

Liquid cimetidine precipitates tube feeding

Proton Pump Inhibitors

Strongly inhibit gastric acid secretion by irreversibly inhibiting the H+-K+ adenosine triphosphatase pump of parietal cells

Uncommon; include diarrhea, nausea, dizziness, and headaches

Lansoprazole (Prevacid)

Omeprazole (Prilosec)

Pantoprazole (Protonix)

Rabeprazole (Aciphex)

Esomeprazole (Nexium)

Optimal: take 30-60 minutes before a meal; swallow whole, do not crush; omeprazole only—may open capsule and sprinkle granules on 1 Tbsp applesauce; avoid alcohol

Nutrition for Disorders of the Gastrointestinal Tract

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access