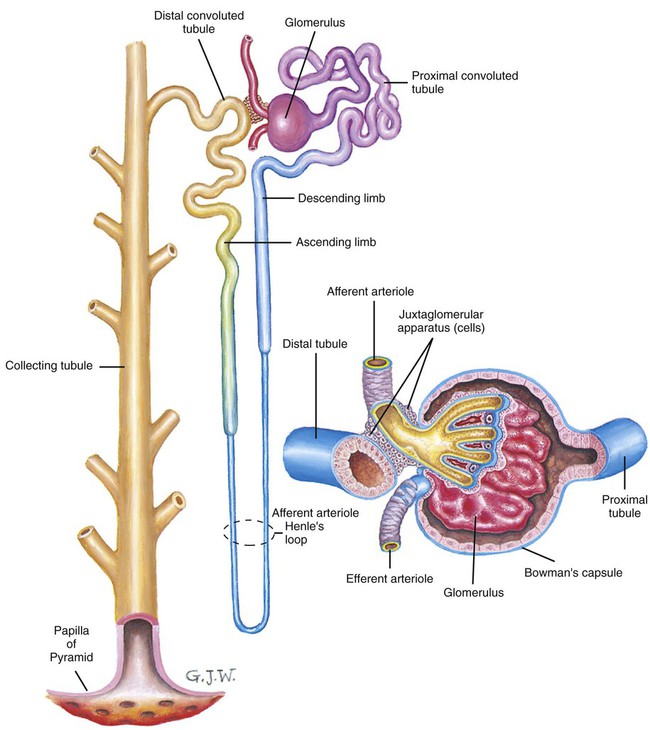

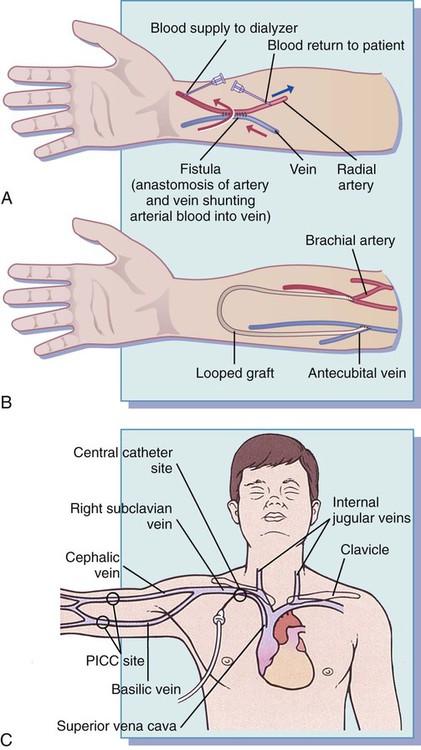

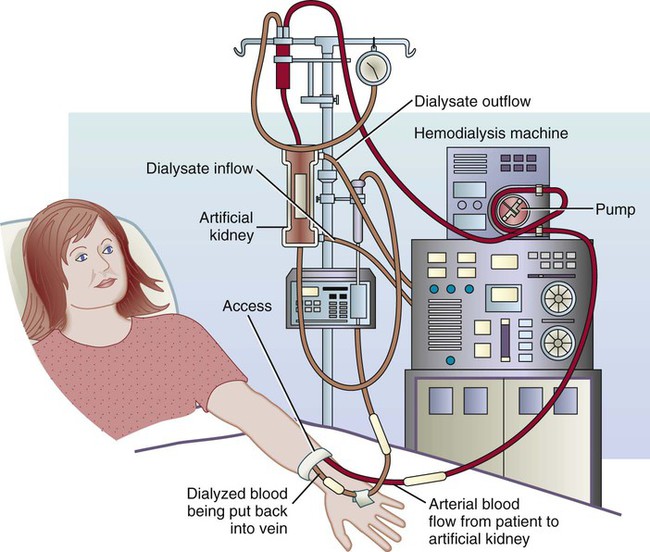

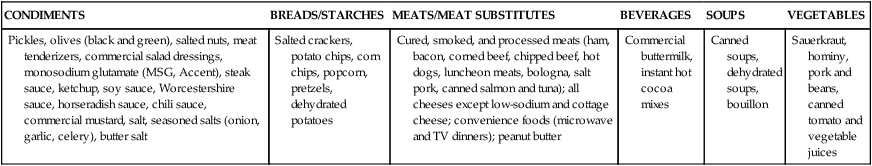

The chief life-preserving function of the kidneys is to maintain chemical homeostasis in the body. They do this largely by processing components within the blood to maintain fluid, electrolyte, and acid-base balance and by eliminating wastes in the urine. Each kidney has approximately 1 million “microscopic” workhorses called nephrons (Figure 21-1). Each nephron filters and resorbs essential blood constituents, secretes ions as needed for maintaining acid-base balance, and excretes fluid and other substances as urine. Other important functions of kidneys include manufacturing hormones to regulate blood pressure (renin), stimulating production of red blood cells (erythropoietin), and regulating calcium and phosphorus metabolism (final step in vitamin D synthesis). Kidneys also detoxify some drugs and poisons (Box 21-1). Nephrotic syndrome is a term used to describe a complex of symptoms that can occur as a result of damage to the capillary walls of the glomerulus. Glomerular damage results in increased urinary excretion of protein (proteinuria) that leads to decreased serum levels of albumin (hypoalbuminemia), hyperlipidemia, and edema.1,2 Nephrotic syndrome is often the result of secondary disease processes: primary glomerular disease (glomerulonephritis), nephropathy secondary to amyloidosis (accumulation of waxy starchlike glycoprotein), diabetes mellitus, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (a chronic inflammatory disease affecting many body systems), or infectious disease. It may be treated with corticosteroid or immunosuppressive medications, but in some patients, nephrotic syndrome is resistant to treatment and may progress to chronic kidney disease (CKD).1,2 It is essential for nursing personnel to monitor patients’ weight and intake and output closely. Intake and output should be documented in the medical record every shift.3 The nurse and dietitian play important roles in developing a nutrition care plan for patients with CKD and in educating them regarding, for example, foods high in sodium (Box 21-2). For the specific sodium content of foods, consult the Food Composition Table on the Evolve website. Primary goals of nutrition therapy are to control hypertension, minimize edema, decrease urinary albumin losses, prevent protein malnutrition and muscle catabolism, supply adequate energy, and slow the progression of renal disease.4,5 Patients need to consume adequate amounts of protein (0.7 to 1 g/kg/day) and energy (35 kcal/kg/day) to prevent catabolism of lean body tissue and avoid malnutrition. Total fat intake should provide less than 30% of total energy needs. Complex carbohydrates should provide the majority of a patient’s kcal because protein, and possibly fat intake, should be limited.5 Limiting dietary sodium can help control hypertension and edema. Commercial preparation and processing of foods, especially convenience foods, often adds substantial amounts of sodium (see Chapter 8). Patients should also be mindful of possible hidden sources of salt (e.g., water supply, medications). In addition, toothpaste and mouthwash often contain a significant amount of sodium; therefore, patients should be instructed not to swallow these products (Box 21-3). Acute kidney failure (AKF) is characterized by an abrupt loss of renal function that may or may not be accompanied by oliguria or anuria.1,2,6,7 The most common cause of AKF is acute tubular necrosis (ATN), which is generally described as postischemic (injury after decreased blood supply) or nephrotoxic (toxic to a kidney).1,7 Although a few patients do not experience any reduction in urine output, two thirds experience the following three stages:1,2,4,8 1. Oliguric phase (usually present within 24 to 48 hours after initial injury, lasting approximately 1 to 3 weeks): This stage is manifested by clinical signs of (retention of excessive amounts of nitrogenous compounds in the blood), acidosis, high serum potassium, high serum phosphorus, hypertension, anorexia, edema, and risk of water intoxication (indicated by low sodium levels). 2. Diuretic phase (usually lasts approximately 2 to 3 weeks). The output of urine is gradually increased. 3. Recovery phase (usually lasts 3 to 12 months): Kidney function gradually improves, but there may be some residual permanent damage. Body weight should be taken and recorded daily. When patients do not eat, they may lose approximately 0.5 kg/day.3 Conversely, any sudden weight gains suggest excessive fluid retention. Monitoring intake, output, and weight will help differentiate whether weight loss or gain is from fluid retention as opposed to lean body mass or adipose tissue. Fluid retention can mask loss of lean body mass. Nurses and dietitians are the health care professionals who may be called on to assist patients in adhering to prescribed fluid restrictions (see the Teaching Tool box, Suggestions for Coping With Fluid Restrictions, in Chapter 18). Nurses work closely with renal dietitians to coordinate meal planning and nutrition education with patients and their significant others.3 Nutrition education may involve reduced protein, sodium, potassium, and fluid intake. The Food Composition Table on Evolve lists the specific protein, sodium, and potassium content of foods. Nurses should be watchful for constipation as a result of restricted intake of fluids and fresh fruits (most are high in potassium), bed rest, and medication side effects.3 Energy should be provided in sufficient amounts for weight maintenance or to meet the demands of stress accompanying the AKF, usually 30 to 40 kcal/kg.4,5 Fats, oils, simple carbohydrates, and low-protein starches should provide nonprotein kcal. In cases in which dialysis is not necessary for treatment, 0.6 g of protein per kg body weight (but not less than 40 g per day) for unstressed patients is recommended.8 This amount can be increased as kidney function improves. When dialysis is used as part of the medical treatment, protein intake can be liberalized to 1 to 1.4 g/kg.8 In either situation, use of high biologic value or high-quality proteins is recommended.8 Diets containing less than 60 g of protein per day may be deficient in niacin, riboflavin, thiamine, calcium, iron, vitamin B12, and zinc,5 and these nutrients may need to be supplemented during convalescence. During the oliguric stage, sodium may be restricted to 1000 to 2000 mg and potassium to 1000 mg per day. Both sodium and potassium, the principal electrolytes, may be lost during the diuretic phase or during dialysis. Therefore, losses should be replaced as needed depending on urinary volume, serum levels, and frequency of dialysis.5 Box 21-4 lists foods high in potassium. Fluids are usually restricted to the patient’s output (urine, vomitus, and diarrhea) plus 500 mL during the oliguric phase.5,8 During the diuretic phase, large amounts of fluid may be needed to replace losses. Progressive, irreversible loss of kidney function1,2 (excretory endocrine, and metabolic function) can develop over days, months, or years and progress through five stages of chronic kidney disease (CKD).2,3,7 CKD has many causes; some of the most common are glomerulonephritis, nephrosclerosis (necrosis of the renal arterioles, associated with hypertension), obstructive diseases (kidney stones, tumors, congenital birth defects of kidneys and urinary tract), diabetes mellitus, SLE, and illicit use of analgesics or street drugs. Regardless of cause, results will be the same: retention of nitrogenous waste products and fluid and electrolyte imbalances that can affect all body systems. Management focuses on slowing progression and minimizing complications.3 Once CKD progresses to stage 5, management centers on replacement, hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis (PD), and renal transplantation.3 Planning diets for CKD, hemodialysis, and PD patients requires the dietitian to calibrate intakes of fluids, energy, protein, lipids, phosphorus, potassium, sodium, and vitamins and other minerals. It is important to design food combinations that not only include necessary nutrients but also that the patient accepts and enjoys. This task can be overwhelming, but there are specialists—renal dietitians—who do this on a daily basis. The National Renal Diet is often used to develop diet guidelines and meal plans (see Appendix F). Nutritional management depends on method of treatment in addition to medical and nutritional status of the patient.9 Table 21-1 provides a comparison of the treatment methods and primary concerns associated with each. TABLE 21-1 BUN, Blood urea nitrogen; CKD, chronic kidney disease. Data from American Dietetic Association: National renal diet: Professional guide, ed 2, Chicago, 2002, American Dietetic Association and K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification guideline 1. Definition and stages of chronic kidney disease, New York, 2002, National Kidney Foundation. The exact point at which nutrition therapy should begin is highly variable, but conventional wisdom indicates that dietary modifications (Table 21-2) should be initiated as early as possible to minimize uremic toxicity, delay progression of renal disease, and prevent wasting and malnutrition.10,11 This can be accomplished by limiting foods whose metabolic by-products add to buildup of such toxic substances and by providing adequate kcal to prevent body tissue catabolism. Patients often find this diet difficult to follow for a long period; therefore, motivation and encouragement from nursing and other health professionals are crucial. TABLE 21-2 CKD, Chronic kidney disease; HBV, high biological value; IBW, ideal body weight. From National Kidney Foundation Dialysis Outcomes Quality Initiative: Clinical practice guidelines for nutrition in chronic renal failure, 2000, New York, 2001, National Kidney Foundation. Accessed April 10, 2010, from www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/guidelines_updates/doqi_nut.html; Wilkens KG, Juneja V: Medical nutrition therapy for renal disorders. In Mahan K, Escott-Stump S, eds: Krause’s food & nutrition therapy, ed 12, St. Louis, 2008, Saunders. In view of the fact that malnutrition is so clearly associated with mortality in renal failure, continuing to assess nutritional status and dietary compliance of patients with CRF is important.12 Because patients may find that foods “don’t taste like they used to,” encouraging use of spices such as garlic, onions, and oregano to enhance the flavor of allowed foods can be helpful.3 The National Renal Diet was developed by the Renal Dietitians Practice Group, American Dietetic Association, and National Kidney Foundation Council on Renal Nutrition to provide a renal diet with nationwide applicability. Diet prescription guidelines for pre stage 5 CKD, hemodialysis, and peritoneal dialysis patients were developed over a 5-year period. Because of the national focus of these guidelines, ethnic and geographically unique foods are not included but can be incorporated as part of the individualized diet plan. Vegetarian choices also are not included because high biologic value proteins (eggs, meats, poultry, game, fish, soy, and dairy products) are the preferred protein sources for renal patients, and some foods in vegan diets are of low biologic value. Ovo-vegetarian and lacto-ovovegetarian diets include high biologic value protein sources, but they also tend to be high in phosphorus. One point that requires emphasis is that the National Renal Diet guidelines and food lists are only a starting point for individualized meal plans and education. Patient compliance may be enhanced by designing meal plans to meet the specific needs of each patient. Box 21-5 provides a sample menu for a patient with CKD. During hemodialysis (HD) blood is shunted by way of a special vascular access or shunt (usually in the nondominant forearm), heparinized, cleansed of excess fluid and waste products through a semipermeable membrane, and then returned to the patient’s circulation (Figure 21-2).1,7 The dialysate (dialysis solution) is an electrolyte solution similar to the composition of normal plasma. Each constituent may be varied according to the patient’s needs, the most common being potassium.3 Average treatment lasts 3 to 6 hours and is usually performed three times per week (Figure 21-3). HD can be performed in a dialysis unit by trained staff. Patients who have received special training may assist in their treatment. Individual diet prescriptions (see Table 21-2) are determined by residual kidney function, dialysate components, duration of dialysis, and rate of blood flow through the artificial kidney.8 The meal plan is designed, monitored, and reevaluated by the dietitian. Nurses and others on the medical team are crucial for providing positive reinforcement and encouragement to the patient and family members on an ongoing basis. Objectives for nutrition therapy are to attain or maintain good nutritional status, prevent excessive accumulation of waste products and fluid between treatments, and minimize the effects of metabolic disorders that occur as a result of CKD.13 Recommendations for protein are intended to counteract protein losses during dialysis, abnormalities in protein metabolism, altered albumin turnover, increased amino acid degradation attributable to metabolic acidosis, inflammation, and infection. The recommended protein intake for patients receiving HD ≥ is 1.2 g protein/kg standard body weight per day with at least 50% of the dietary protein of high biologic value.13 Energy expenditure in HD patients is similar to healthy individuals. For adult patients younger than age 60, daily energy intake of 35 kcal/kg of standard body weight is recommended. Obese individuals and adults older than age 60 may benefit from 30 to 35 kcal/kg of body weight.13 Patients receiving HD are at risk for lipid metabolism disorders. As such, less than 30% of total kcal should be from fat, less than 10% of total kcal should be from saturated fat. Dietary cholesterol should be less than 300 mg/day. Restricting cholesterol and energy intake from fats less than these levels may not be beneficial because the decreased energy intake may lead to malnutrition.13 Sodium and fluid restrictions should be individualized to keep in check intradialytic weight gains, blood pressure control, and residual renal function. The recommended intradialytic fluid gains is less than 5% of the patient’s dry weight.13 Corresponding sodium and fluids restrictions are as follows:13

Nutrition for Diseases of the Kidneys

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grodner/foundations/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grodner/foundations/ ![]() Nutrition Concepts Online

Nutrition Concepts Online

Kidney Function

Nephrotic Syndrome

Nutrition Therapy

Acute Kidney Failure

Nutrition Therapy

Chronic Kidney Disease

Nutrition Therapy

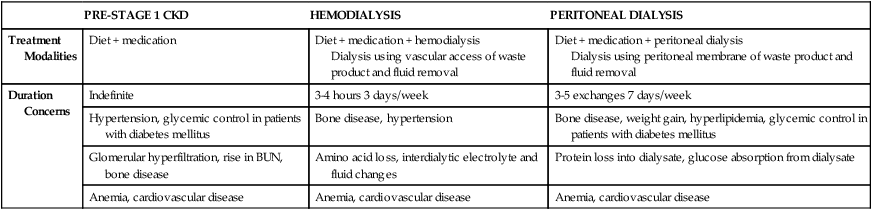

PRE-STAGE 1 CKD

HEMODIALYSIS

PERITONEAL DIALYSIS

Treatment Modalities

Diet + medication

Diet + medication + hemodialysis

Dialysis using vascular access of waste product and fluid removal

Diet + medication + peritoneal dialysis

Dialysis using peritoneal membrane of waste product and fluid removal

Duration Concerns

Indefinite

3-4 hours 3 days/week

3-5 exchanges 7 days/week

Hypertension, glycemic control in patients with diabetes mellitus

Bone disease, hypertension

Bone disease, weight gain, hyperlipidemia, glycemic control in patients with diabetes mellitus

Glomerular hyperfiltration, rise in BUN, bone disease

Amino acid loss, interdialytic electrolyte and fluid changes

Protein loss into dialysate, glucose absorption from dialysate

Anemia, cardiovascular disease

Anemia, cardiovascular disease

Anemia, cardiovascular disease

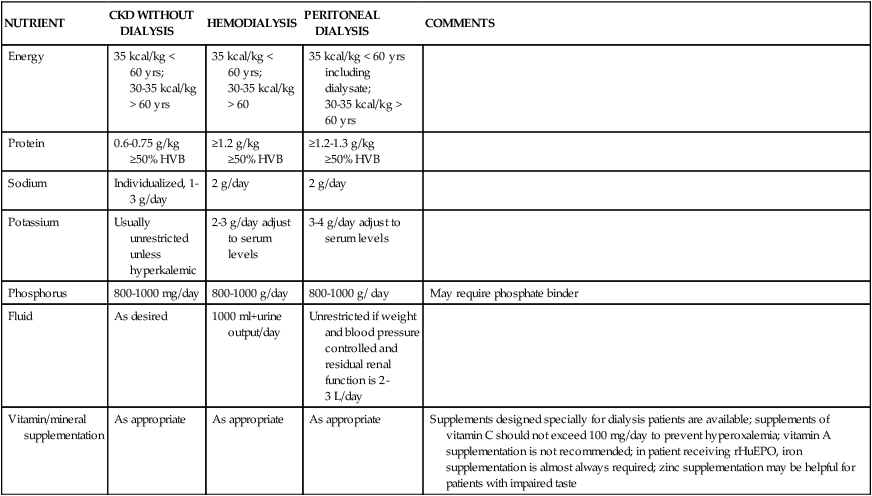

NUTRIENT

CKD WITHOUT DIALYSIS

HEMODIALYSIS

PERITONEAL DIALYSIS

COMMENTS

Energy

35 kcal/kg < 60 yrs;

30-35 kcal/kg > 60 yrs

35 kcal/kg < 60 yrs;

30-35 kcal/kg > 60

35 kcal/kg < 60 yrs including dialysate;

30-35 kcal/kg > 60 yrs

Protein

0.6-0.75 g/kg

≥50% HVB

≥1.2 g/kg

≥50% HVB

≥1.2-1.3 g/kg

≥50% HVB

Sodium

Individualized, 1-3 g/day

2 g/day

2 g/day

Potassium

Usually unrestricted unless hyperkalemic

2-3 g/day adjust to serum levels

3-4 g/day adjust to serum levels

Phosphorus

800-1000 mg/day

800-1000 g/day

800-1000 g/ day

May require phosphate binder

Fluid

As desired

1000 ml+urine output/day

Unrestricted if weight and blood pressure controlled and residual renal function is 2-3 L/day

Vitamin/mineral supplementation

As appropriate

As appropriate

As appropriate

Supplements designed specially for dialysis patients are available; supplements of vitamin C should not exceed 100 mg/day to prevent hyperoxalemia; vitamin A supplementation is not recommended; in patient receiving rHuEPO, iron supplementation is almost always required; zinc supplementation may be helpful for patients with impaired taste

Hemodialysis

Nutrition Therapy

Protein and Energy

Fat

Sodium, Potassium, and Fluid

cup)

cup) cup)

cup) cup)

cup) cup)

cup) cup)

cup)