Nutrition for Childbearing

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

• Explain the importance of adequate nutrition and weight gain during pregnancy.

• Compare the nutrient needs of pregnant and nonpregnant women.

• Describe common factors that influence a woman’s nutritional status and choices.

• Describe how common nutritional risk factors affect nutritional requirements during pregnancy.

• Apply the nursing process to nutrition during pregnancy, postpartum, and lactation.

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/McKinney/mat-ch/

At no time in a woman’s life is nutrition as important as it is during pregnancy and lactation when she must nourish her own body and that of her baby. Nurses have ongoing contact with women and can provide education about nutritional needs throughout this period. This is especially important because many women do not adequately understand the nutritional needs of pregnancy. Nutritional counseling can also be offered before conception to improve chances of a healthy pregnancy.

Weight Gain During Pregnancy

Weight gain during pregnancy, especially after the first trimester, is an important determinant of fetal growth. Insufficient weight gain during pregnancy has been associated with low birth weight (less than 2500 g, or 5.5 lb), small-for-gestational age infants, preterm birth, and failure to initiate breastfeeding. Poor maternal weight gain indicates not only lower caloric intake but also low intake of other important nutrients. Excessive weight gain is another problem. It is associated with increased birth weight (macrosomia), cesarean birth, postpartum weight retention, low Apgar scores, hypoglycemia, and overweight in children (American Dietetic Association [ADA], 2008; Viswanathan, Siega-Riz, Moos, et al., 2008).

Recommendations for Total Weight Gain

Recommendations for weight gain in pregnancy are based on the woman’s prepregnancy weight for her height or her body mass index (BMI). BMI is calculated by dividing the weight in kilograms by the height in meters squared. Another method is to divide the weight in pounds by the height in inches squared and multiply the result by 703 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2009). Tables are available that show the BMI for various weights and heights.

Suggested gains vary according to the woman’s BMI (or weight for height) before pregnancy (Table 14-1). The recommended weight gain during pregnancy is 11.5 to 16 kg (25 to 35 lb) for women who begin pregnancy at normal BMI. The range allows for individual differences because no exact weight gain is appropriate for every woman.

TABLE 14-1

RECOMMENDED WEIGHT GAIN DURING PREGNANCY

| WEIGHT BEFORE PREGNANCY | TOTAL GAIN | MEAN (Range) WEEKLY GAIN (2nd AND 3rd TRIMESTERS)∗ |

| Normal weight (BMI 18.5-24.9) | 11.5-16 kg 25-35 lb | 0.42 (0.35-0.5) kg 1 (0.8-1) lb |

| Underweight (BMI <18.5) | 12.5-18 kg 28-40 lb | 0.51 (0.44-0.58) kg 1 (1-1.3) lb |

| Overweight (BMI 25-29.9) | 7-11.5 kg 15-25 lb | 0.28 (0.23-0.33) kg 0.6 (0.5-0.7) lb |

| Obese (BMI 30 or higher) | 5-9 kg 11-20 lb | 0.22 (0.17-0.27) kg 0.5 (0.4-0.6) lb |

∗Recommended weight gain during the first trimester is 0.5-2 kg (1.1-4.4 lb). Data from Rasmussen, K. M., & Yaktine, A. L. (Eds.).(2009). Weight gain during pregnancy: Reexamining the guidelines. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Women who are underweight should gain more to meet the needs of pregnancy as well as to meet their own need to gain weight. They should gain 12.5 to 18 kg (28 to 40 lb). The recommended gain for overweight women is 7 to 11.5 kg (15 to 25 lb).

Obesity is a growing problem. Obese women who become pregnant have an increased incidence of spontaneous abortion, gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, prolonged labor, cesarean birth, postpartum hemorrhage, wound complications, macrosomia, and congenital anomalies (Bond, 2011; Cunningham, Leveno, Bloom, et al., 2010; Stotland, 2009; Yogev & Catalano, 2009). Their children have an increased risk of childhood obesity (Josefson, 2011). Overweight and obese women should be advised to lose weight before conception to achieve the best pregnancy outcomes. The recommended weight gain for the obese woman is 5 to 9 kg (11 to 20 lb) to provide sufficient nutrients for the fetus.

Lower weight gain or weight loss for obese women during pregnancy is not recommended at this time as there is insufficient evidence about the effect on neurologic development of the infant. More research is needed in this area (Rasmussen & Yaktine, 2009)

In the past, women of small stature were advised to gain to the lower limits of the recommended range for their prepregnancy weight. Adolescents were advised to gain to the upper limits of their prepregnancy weight. However, evidence to support these guidelines has not been found. Therefore, these women should gain according to the recommendations for their BMI (Rasmussen & Yaktine, 2009).

Infants of a multifetal pregnancy are often born before term and tend to weigh less than infants born of single pregnancies. A greater weight gain in the mother may help prevent low birth weight. The recommended gain for women of normal prepregnancy weight who are carrying twins is 17 to 25 kg (37 to 54 lb) (Ramussen & Yaktine, 2009). When these women meet the recommended weight gain, they are less likely to deliver their twins before 32 weeks of gestation, and the infants are more likely to weigh more than 2500 gm (5.5 lb) (Fox, Rebarber, Roman, et al., 2010).

Pattern of Weight Gain

The pattern of weight gain is as important as the total increase. The general recommendation is for an increment of approximately 0.5 to 2 kg (1.1 to 4.4 lb) during the first trimester, when the mother may be nauseated and the fetus needs fewer nutrients for growth. During the rest of the pregnancy, the expected weekly weight gain for women of normal prepregnancy weight is 0.35 to 0.5 kg (0.8 to 1 lb) (Ramussen & Yaktine, 2009).

Maternal and Fetal Distribution

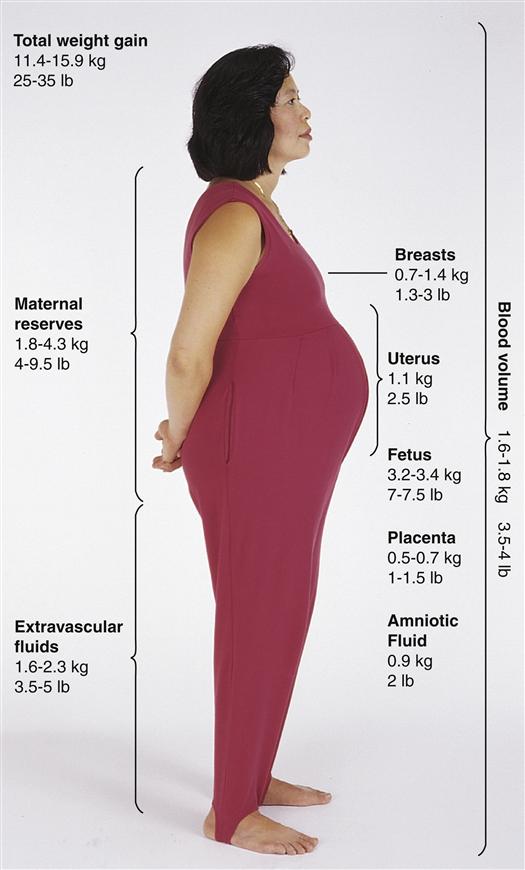

Women often wonder why they should gain so much weight when the fetus weighs so much less. Explaining the distribution of weight helps them understand this need (Figure 14-1).

Factors that Influence Weight Gain

Knowing about factors that may negatively influence nutrient intake and weight gain helps the nurse devise plans for improving nutrition. Women at risk for inadequate weight gain include those who are young, unmarried, low income, poorly educated, in poor general health, or receiving insufficient prenatal care. Multiparas are at higher risk for low weight gain than primiparas. Smoking or substance abuse may interfere with food intake and weight gain.

Nutritional Requirements During Pregnancy

Nutrient needs increase during pregnancy to meet the demands of the mother and fetus. Usually the increases are not large and are relatively easy to obtain through the diet.

Dietary Reference Intakes

In the United States, dietary reference intakes (DRIs) refer to terms that estimate nutrient needs. DRIs include four categories:

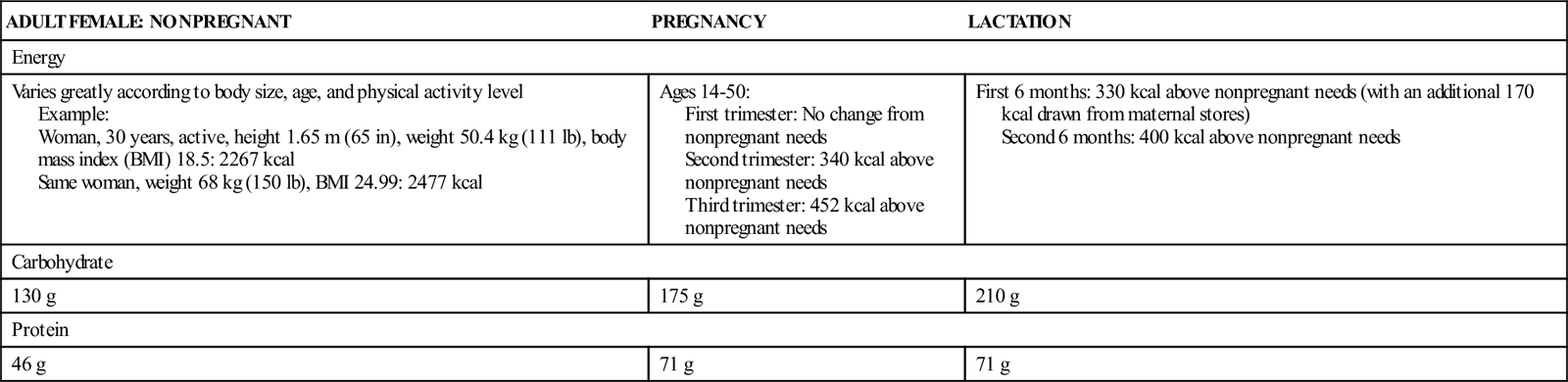

Table 14-2 shows the current recommendations for DRIs for energy, carbohydrates, and protein for adult women.

TABLE 14-2

DIETARY REFERENCE INTAKES: RECOMMENDED ENERGY AND PROTEIN INTAKES

| ADULT FEMALE: NONPREGNANT | PREGNANCY | LACTATION |

| Energy | ||

| Varies greatly according to body size, age, and physical activity level Example: Woman, 30 years, active, height 1.65 m (65 in), weight 50.4 kg (111 lb), body mass index (BMI) 18.5: 2267 kcal Same woman, weight 68 kg (150 lb), BMI 24.99: 2477 kcal | Ages 14-50: First trimester: No change from nonpregnant needs Second trimester: 340 kcal above nonpregnant needs Third trimester: 452 kcal above nonpregnant needs | First 6 months: 330 kcal above nonpregnant needs (with an additional 170 kcal drawn from maternal stores) Second 6 months: 400 kcal above nonpregnant needs |

| Carbohydrate | ||

| 130 g | 175 g | 210 g |

| Protein | ||

| 46 g | 71 g | 71 g |

Data from Institute of Medicine, Food, and Nutrition Board. (2002a). Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrates, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein and amino acids (macronutrients). Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Energy

The energy provided by foods for body processes is calculated in kilocalories. Kilocalories (commonly called calories, the term used in this book) refers to a unit of heat used to show the energy value of foods. Kilocalories are obtained from carbohydrates and proteins, which provide 4 calories in each gram, and fats, which provide 9 calories in each gram.

Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates may be simple or complex. Simple carbohydrates include sucrose (table sugar, candy) and those found in fruits and vegetables. Complex carbohydrates are present in starches, such as cereals, pasta, and potatoes. They supply vitamins, minerals, and fiber. Because of their value in providing other nutrients, complex carbohydrates should be the major source of carbohydrates in the diet. Fiber, the indigestible carbohydrate in plant foods, is important because it produces bulk in the diet. Fiber absorbs water and stimulates peristalsis to help prevent constipation. It also slows gastric emptying, causing a sensation of fullness.

Fats

Fats provide energy and fat-soluble vitamins. When reduction of calories is necessary, it is important to decrease but not eliminate carbohydrates and fats. If carbohydrate and fat intake provides insufficient calories, the body uses protein to meet energy needs. This use decreases the amount of protein available for building and repairing tissue.

Fat intake also is important because it provides essential fatty acids such as alpha linolenic acid and linoleic acid. These help in neurologic and visual development in the fetus. Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) is also important for fetal visual and cognitive development. These fatty acids are found in canola, soybean, and walnut oil, as well as some seafood such as bass or salmon (Nichols-Richardson, 2011a).

Calories

Approximately 80,000 additional calories are needed during pregnancy (Cunningham et al., 2010). These extra calories furnish energy for the production and maintenance of the fetus, placenta, added maternal tissues, and increased basal metabolic rate. Most pregnant women need a daily caloric intake of 2200 to 2900 calories depending on their age, activity level, and prepregnancy BMI (ADA, 2008).

During the first trimester of pregnancy, no added calories are needed. However, the daily caloric intake for pregnant women should increase by 340 calories during the second trimester and 452 calories during the third trimester (Institute of Medicine, Food, and Nutrition Board, 2002). This increase can be achieved relatively easily with a variety of foods and only a small increase in food.

Nutrient density, the quantity and quality of the various nutrients in each 100 calories of food, is an important consideration. Foods of high nutrient density have large amounts of quality nutrients per serving. During pregnancy the increased need for most nutrients may not be met unless calories are selected carefully. The term empty calories refers to foods that are high in calories but low in other nutrients. Many snack foods contain excessive calories and low nutrient density and are high in fat and sodium. Increased calories should be “spent” on foods that provide the nutrients needed in increased amounts during pregnancy.

Women often use sugar substitutes to reduce their caloric intake. Saccharin (Sweet’N Low), sucralose (Splenda), and aspartame (Equal or NutraSweet) are considered safe for normal women during pregnancy. However, women with phenylketonuria lack the enzyme to metabolize aspartame and should never use it because it could lead to maternal and fetal brain damage (Pronsky & Crowe, 2012).

Protein

Protein is necessary for metabolism, tissue synthesis, and tissue repair. The daily protein RDA for females is 46 g, depending on their age and size. During the second half of pregnancy, a protein intake of 71 g each day is recommended to expand the blood volume and support the growth of maternal and fetal tissues. This is an increase of 25 g of protein daily (Erick, 2012).

Protein is generally abundant in diets in most industrialized nations, but diets low in caloric intake may also be low in protein. If calories are low and protein is used to provide energy, fetal growth may be impaired.

The nurse should counsel women at risk for poor protein intake how to determine protein intake and increase food sources. When a woman needs to increase her intake, she should eat more protein-rich foods rather than use high-protein powders or drinks. Protein substitutes do not have the other nutrients provided by foods.

Vitamins

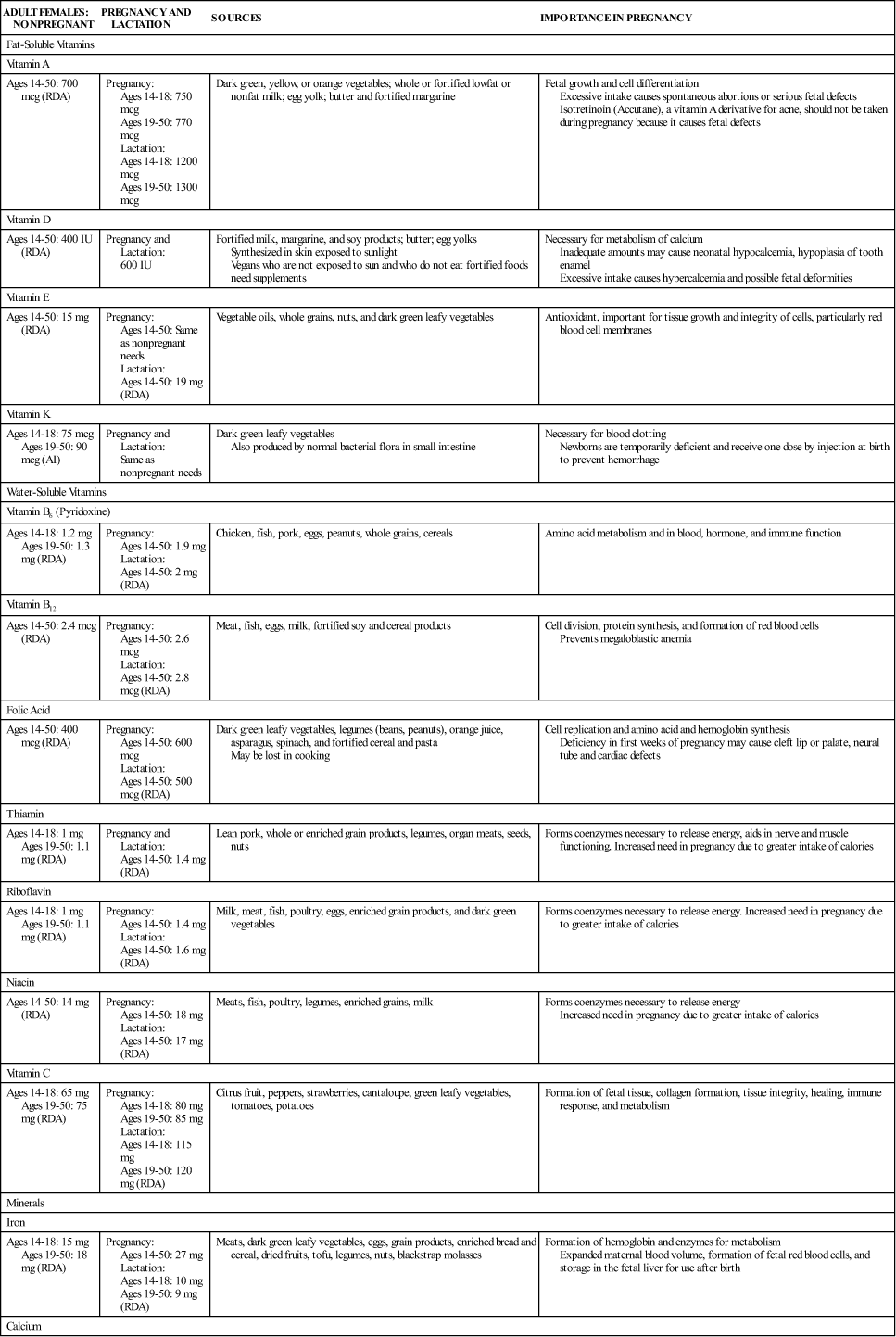

For most people, the daily intake of each vitamin is not always as high as recommended, but true deficiency states are uncommon in North America. Recommendations for vitamin intake and food sources are shown in Table 14-3.

TABLE 14-3

DIETARY REFERENCE INTAKES: RECOMMENDATIONS FOR VITAMINS AND MINERALS

| ADULT FEMALES: NONPREGNANT | PREGNANCY AND LACTATION | SOURCES | IMPORTANCE IN PREGNANCY |

| Fat-Soluble Vitamins | |||

| Vitamin A | |||

| Ages 14-50: 700 mcg (RDA) | Pregnancy: Ages 14-18: 750 mcg Ages 19-50: 770 mcg Lactation: Ages 14-18: 1200 mcg Ages 19-50: 1300 mcg | Dark green, yellow, or orange vegetables; whole or fortified lowfat or nonfat milk; egg yolk; butter and fortified margarine | Fetal growth and cell differentiation Excessive intake causes spontaneous abortions or serious fetal defects Isotretinoin (Accutane), a vitamin A derivative for acne, should not be taken during pregnancy because it causes fetal defects |

| Vitamin D | |||

| Ages 14-50: 400 IU (RDA) | Pregnancy and Lactation: 600 IU | Fortified milk, margarine, and soy products; butter; egg yolks Synthesized in skin exposed to sunlight Vegans who are not exposed to sun and who do not eat fortified foods need supplements | Necessary for metabolism of calcium Inadequate amounts may cause neonatal hypocalcemia, hypoplasia of tooth enamel Excessive intake causes hypercalcemia and possible fetal deformities |

| Vitamin E | |||

| Ages 14-50: 15 mg (RDA) | Pregnancy: Ages 14-50: Same as nonpregnant needs Lactation: Ages 14-50: 19 mg (RDA) | Vegetable oils, whole grains, nuts, and dark green leafy vegetables | Antioxidant, important for tissue growth and integrity of cells, particularly red blood cell membranes |

| Vitamin K | |||

| Ages 14-18: 75 mcg Ages 19-50: 90 mcg (AI) | Pregnancy and Lactation: Same as nonpregnant needs | Dark green leafy vegetables Also produced by normal bacterial flora in small intestine | Necessary for blood clotting Newborns are temporarily deficient and receive one dose by injection at birth to prevent hemorrhage |

| Water-Soluble Vitamins | |||

| Vitamin B6 (Pyridoxine) | |||

| Ages 14-18: 1.2 mg Ages 19-50: 1.3 mg (RDA) | Pregnancy: Ages 14-50: 1.9 mg Lactation: Ages 14-50: 2 mg (RDA) | Chicken, fish, pork, eggs, peanuts, whole grains, cereals | Amino acid metabolism and in blood, hormone, and immune function |

| Vitamin B12 | |||

| Ages 14-50: 2.4 mcg (RDA) | Pregnancy: Ages 14-50: 2.6 mcg Lactation: Ages 14-50: 2.8 mcg (RDA) | Meat, fish, eggs, milk, fortified soy and cereal products | Cell division, protein synthesis, and formation of red blood cells Prevents megaloblastic anemia |

| Folic Acid | |||

| Ages 14-50: 400 mcg (RDA) | Pregnancy: Ages 14-50: 600 mcg Lactation: Ages 14-50: 500 mcg (RDA) | Dark green leafy vegetables, legumes (beans, peanuts), orange juice, asparagus, spinach, and fortified cereal and pasta May be lost in cooking | Cell replication and amino acid and hemoglobin synthesis Deficiency in first weeks of pregnancy may cause cleft lip or palate, neural tube and cardiac defects |

| Thiamin | |||

| Ages 14-18: 1 mg Ages 19-50: 1.1 mg (RDA) | Pregnancy and Lactation: Ages 14-50: 1.4 mg (RDA) | Lean pork, whole or enriched grain products, legumes, organ meats, seeds, nuts | Forms coenzymes necessary to release energy, aids in nerve and muscle functioning. Increased need in pregnancy due to greater intake of calories |

| Riboflavin | |||

| Ages 14-18: 1 mg Ages 19-50: 1.1 mg (RDA) | Pregnancy: Ages 14-50: 1.4 mg Lactation: Ages 14-50: 1.6 mg (RDA) | Milk, meat, fish, poultry, eggs, enriched grain products, and dark green vegetables | Forms coenzymes necessary to release energy. Increased need in pregnancy due to greater intake of calories |

| Niacin | |||

| Ages 14-50: 14 mg (RDA) | Pregnancy: Ages 14-50: 18 mg Lactation: Ages 14-50: 17 mg (RDA) | Meats, fish, poultry, legumes, enriched grains, milk | Forms coenzymes necessary to release energy Increased need in pregnancy due to greater intake of calories |

| Vitamin C | |||

| Ages 14-18: 65 mg Ages 19-50: 75 mg (RDA) | Pregnancy: Ages 14-18: 80 mg Ages 19-50: 85 mg Lactation: Ages 14-18: 115 mg Ages 19-50: 120 mg (RDA) | Citrus fruit, peppers, strawberries, cantaloupe, green leafy vegetables, tomatoes, potatoes | Formation of fetal tissue, collagen formation, tissue integrity, healing, immune response, and metabolism |

| Minerals | |||

| Iron | |||

| Ages 14-18: 15 mg Ages 19-50: 18 mg (RDA) | Pregnancy: Ages 14-50: 27 mg Lactation: Ages 14-18: 10 mg Ages 19-50: 9 mg (RDA) | Meats, dark green leafy vegetables, eggs, grain products, enriched bread and cereal, dried fruits, tofu, legumes, nuts, blackstrap molasses | Formation of hemoglobin and enzymes for metabolism Expanded maternal blood volume, formation of fetal red blood cells, and storage in the fetal liver for use after birth |

| Calcium | |||

| Ages 14-18: 1300 mg Ages 19-50: 1000 mg (AI) | Pregnancy and Lactation: Same as nonpregnant needs | Dairy products, salmon, sardines with bones, legumes, fortified juice, tofu, broccoli | Fetal bone and teeth formation, cell membrane permeability, coagulation, and neuromuscular function |

| Zinc | |||

| Ages 14-18: 9 mg Ages 19-50: 8 mg (RDA) | Pregnancy: Ages 14-18: 12 mg Ages 19-50: 11 mg Lactation: Ages 14-18: 13 mg Ages 19-50: 12 mg (RDA) | Meat, poultry, seafood, eggs, nuts, seeds, legumes, wheat germ, whole grains, yogurt | Fetal and maternal tissue growth, cell differentiation and reproduction, DNA and RNA synthesis, metabolism, acid-base balance |

| Magnesium | |||

| Ages 14-18: 360 mg Ages 19-30: 310 mg Ages 31-50: 320 mg (RDA) | Pregnancy: Ages 14-18: 400 mg Ages 19-30: 350 mg Ages 31-50: 360 mg Lactation: Same as nonpregnant needs | Whole grains, nuts, legumes, dark green vegetables, small amounts in many foods | Cell growth and neuromuscular function; activates enzymes for metabolism of protein and energy |

| Iodine | |||

| Ages 14-50: 150 mcg (RDA) | Pregnancy: Ages 14-50: 220 mcg Lactation: Ages 14-50: 290 mcg (RDA) | Seafood, iodized salt | Important in thyroid function Deficiency may cause abortion, stillbirth, congenital hypothyroidism, neurologic conditions |

AI, Adequate intake; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; RDA, recommended daily allowance; RNA, ribonucleic acid.

Dietary reference intakes are listed as RDA or AI.

Data from Institute of Medicine (IOM), Food and Nutrition Board (FNB). (1997). Dietary reference intakes for calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, vitamin D, and fluoride. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; IOM, FNB. (1998). Dietary reference intakes for thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, vitamin B6, folate, vitamin B12, pantothenic acid, biotin, and choline. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; IOM, FNB. (2000). Dietary reference intakes for vitamin C, vitamin E, selenium, and carotenoids. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; IOM, FNB. (2001). Dietary reference intakes for vitamin A, vitamin K, arsenic, boron, chromium, copper, iodine, iron, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, silicon, vanadium, and zinc. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; IOM, FNB. (2011). Dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

The fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) are stored in the liver. Deficiency states are not likely to occur, but fat-soluble vitamins can be toxic in excessive amounts. For example, too much vitamin A can cause fetal defects. The nurse should ask about vitamins and medications taken by pregnant women and alert them about the dangers of excess vitamins.

Water-soluble vitamins (B6, B12, and C, folic acid, thiamin, riboflavin, and niacin) are not stored in the body as well as fat-soluble vitamins. Therefore they should be included in the daily diet. Because excess amounts are excreted in the urine, there is less chance of toxicity from excessive intake, but it can occur with megadoses. These vitamins are easily transferred from food to water in cooking. Foods should be steamed, microwaved, or prepared in only small amounts of water. The remaining water can be used in other dishes, such as soups.

Folic Acid

Folic acid (also called folate) can decrease the occurrence of neural tube defects, such as spina bifida and anencephaly, in newborns. It may also help prevent cleft lip, cleft palate, and some heart defects (CDC, 2010; Peckenpaugh, 2010). Adequate intake of folic acid is especially important just before conception and during the first trimester of pregnancy. Because about half of pregnancies are unplanned, all women of childbearing age should consume adequate amounts of folic acid each day. A Healthy People 2020 goal is for women of childbearing potential to take in at least 400 mcg of folic acid each day (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010).

In the past, the recommended amount of folic acid for women capable of childbearing has been 400 mcg (0.4 mg), but the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) now recommends 400 mcg to 800 mcg (0.4 mg to 0.8 mg) each day. The dose should be taken for at least 1 month before conception and for 2 to 3 months after conception (USPSTF, 2009). There has been no change in the recommendation of 600 mcg (0.6 mg) of folic acid daily for the rest of pregnancy.

Women who are taking anticonvulsant drugs or who have previously had an infant born with a neural tube defect should take 4 mg daily before conception and during the first trimester (CDC, 2010; Johnson, Gregory, & Niebyl, 2007). This practice can decrease the risk of recurrence of neural tube defects by 80% (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP] & American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], 2007).

Women often do not realize the importance of folic acid in their diet before pregnancy begins, and many do not meet the recommended level, in spite of a national campaign to make the public more aware of this problem. One third of births occur to women age 18 to 24 years, but women in this group have lower intake of supplements containing folic acid and less knowledge of the need for folic acid than older women (CDC, 2008). More education is necessary to increase folic acid use in women of childbearing age. Because of its importance, folic acid is added to all enriched cereal grain products.

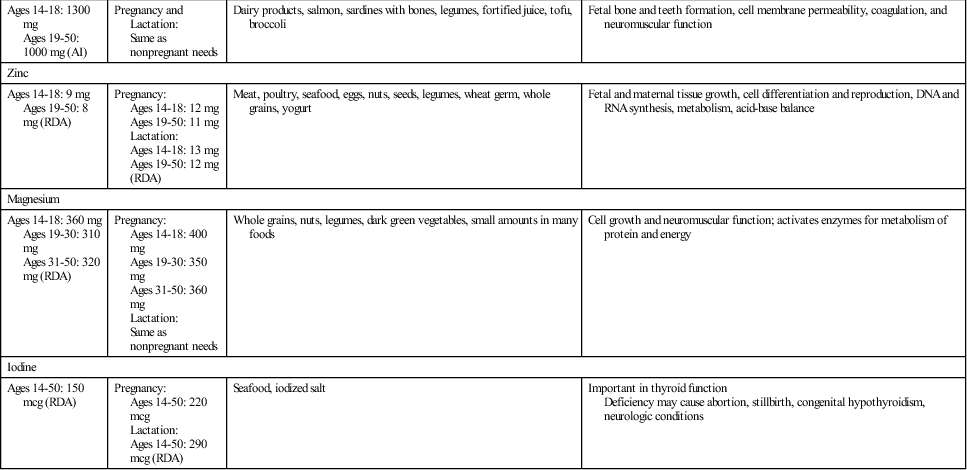

Minerals

Most minerals are supplied in adequate amounts in normal diets. However, dietary intake of iron and calcium may be below recommended levels in women of childbearing age (Grodner, Roth, & Walkingshaw, 2012). Recommendations for mineral intake and food sources are shown in Table 14-3.

Iron

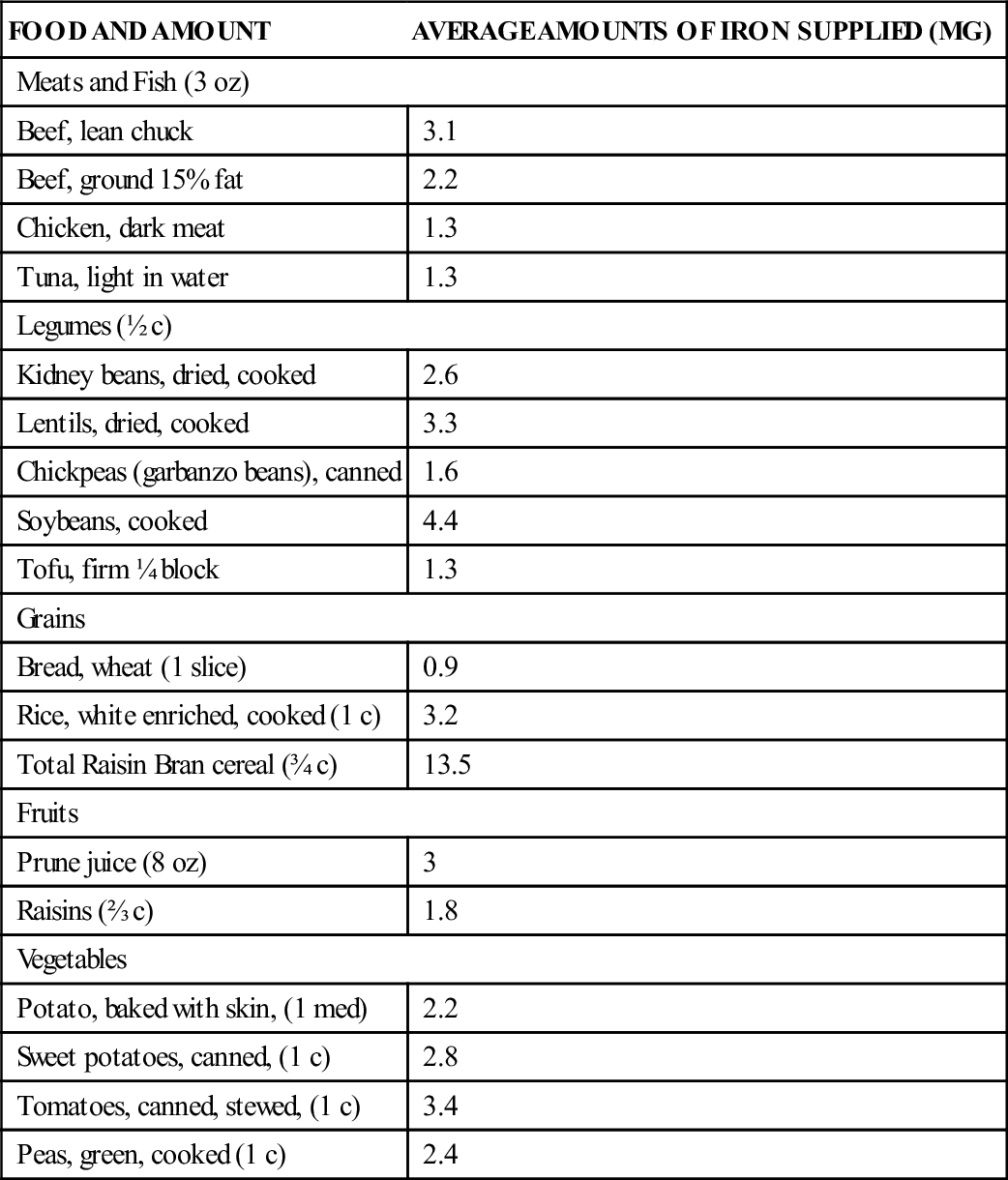

Approximately 1000 mg of absorbed iron is needed during pregnancy (Cunningham et al., 2010). This provides for the 20% to 30% increase in maternal red blood cells and for transfer to the fetus for storage and production of red blood cells (Blackburn, 2013). Infants use stored iron during the first 4 to 6 months, when their intake of iron is low. Iron is probably the only nutrient that cannot be supplied completely and easily from the diet during pregnancy. Table 14-4 lists common foods high in iron.

TABLE 14-4

| FOOD AND AMOUNT | AVERAGE AMOUNTS OF IRON SUPPLIED (MG) |

| Meats and Fish (3 oz) | |

| Beef, lean chuck | 3.1 |

| Beef, ground 15% fat | 2.2 |

| Chicken, dark meat | 1.3 |

| Tuna, light in water | 1.3 |

| Legumes (½ c) | |

| Kidney beans, dried, cooked | 2.6 |

| Lentils, dried, cooked | 3.3 |

| Chickpeas (garbanzo beans), canned | 1.6 |

| Soybeans, cooked | 4.4 |

| Tofu, firm ¼ block | 1.3 |

| Grains | |

| Bread, wheat (1 slice) | 0.9 |

| Rice, white enriched, cooked (1 c) | 3.2 |

| Total Raisin Bran cereal (¾ c) | 13.5 |

| Fruits | |

| Prune juice (8 oz) | 3 |

| Raisins (⅔ c) | 1.8 |

| Vegetables | |

| Potato, baked with skin, (1 med) | 2.2 |

| Sweet potatoes, canned, (1 c) | 2.8 |

| Tomatoes, canned, stewed, (1 c) | 3.4 |

| Peas, green, cooked (1 c) | 2.4 |

Data from United States Department of Agriculture. (2011). USDA national nutrient database for standard reference. Retrieved from www.ars.usda.gov/Services/docs.htm?docid=20958.

Many adult women do not meet their daily nonpregnancy requirement for iron and begin pregnancy already anemic or with low iron stores (see Chapter 26). Women often have only 100 mg of nonhemoglobin iron stored at the beginning of pregnancy (Hall, 2011). Iron is transferred to the fetus even if the mother is anemic, so adequate intake is necessary to keep the mother’s iron supply at normal levels (Cunningham et al., 2010).

Iron is present in many foods, but in small amounts. Approximately 25% of iron from animal sources (called heme iron) is absorbed. Only about 5% of nonheme iron (iron from plant sources and fortified foods) is absorbed (Gallagher, 2012). Absorption of iron is affected by intake of other substances. Calcium and phosphorus in milk and tannin in tea decrease iron absorption from nonheme iron if they are consumed during the same meal. Coffee binds iron, preventing it from being fully absorbed. Antacids, phytates (in grains and vegetables), oxalic acid (in spinach), and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA, a food additive) also decrease absorption. Foods cooked in iron pans contain more iron (Yoder, 2009). Foods containing ascorbic acid and meat, fish, or poultry eaten with nonheme iron–containing foods may increase absorption.

Because of the difficulty of obtaining enough iron in the diet, health care providers often prescribe iron supplements of 30 mg/day during pregnancy. Women who are anemic may need 60 to 120 mg/day. Women who take high doses of iron also need zinc and copper supplements because iron interferes with the absorption and use of these minerals (Nix, 2009). Supplementation may begin during the second trimester, when the need increases and morning sickness has usually ended.

Iron taken between meals is absorbed more completely, but many women find the side effects worse when iron is taken without food. Side effects occur more often with higher doses and include nausea, vomiting, heartburn, epigastric pain, constipation, diarrhea, and black stools. Taking iron at bedtime may make it easier to tolerate. For best absorption, it should be taken with water or juice but not with coffee, tea, or milk.

Women should be reminded to keep iron, like all other medicines, out of the reach of children. Accidental overdose with iron is a leading cause of childhood poisoning.

Calcium

Calcium is transferred to the fetus, especially in the last trimester, and is important for mineralization of fetal bones and teeth. Although a small amount of calcium is removed from the mother’s bones, it is insignificant and does not affect maternal bone mass. A common myth is that calcium is removed from the teeth during pregnancy, leading to excessive decay. Actually, calcium in the teeth is stable and is not affected by pregnancy.

Calcium absorption and retention increases during the pregnancy, and it is stored for use in the third trimester when fetal needs are greatest. Women 18 years and younger need more calcium because their bone density is not complete. Calcium needs are unchanged during pregnancy and lactation.

The best source of calcium is dairy products. Whole, low-fat, and nonfat milk all contain the same amount of calcium and may be used interchangeably to increase or reduce calorie intake. However, women with lactose intolerance (lactase deficiency resulting in gastrointestinal problems when dairy products are consumed) need other sources of calcium (Box 14-1).

Although spinach and chard contain calcium, they also contain oxalates that decrease calcium availability and make them poor sources. Large amounts of fiber also interfere with calcium absorption. Caffeine increases the excretion of calcium.

Women who eat inadequate amounts of calcium-rich foods or avoid dairy products because of lactose intolerance, to avoid eating animal products or for other reasons should take supplements. To ensure absorption of calcium, women should take supplements with meals, separately from iron supplements. Taking calcium with vitamin D also increases absorption.

Sodium

Sodium needs are increased during pregnancy to provide for an expanded blood volume and the needs of the fetus. Although sodium is not restricted during pregnancy, excessive amounts should be avoided. Women are advised that a moderate intake of salt or the salting of foods to taste is acceptable, but that intake of high-sodium foods (Box 14-2) should be limited.

Nutritional Supplementation

Purpose

Food is the best source for nutrients. Although health care providers frequently prescribe prenatal vitamin-mineral supplements and many women expect to take them, supplementation may not be necessary during pregnancy if the diet is adequate. The exceptions are iron and folic acid, which may not be obtained in adequate amounts through normal food intake. Expectant mothers who are vegetarians, lactose intolerant, or have special problems in obtaining nutrients through diet alone may need supplements. Assessment of each woman’s needs determines whether supplementation is appropriate.

Disadvantages and Dangers of Nutritional Supplementation

Because they believe supplements are a harmless way to improve their diets, some women take large amounts without consulting a health care provider. No standardization or regulation of the amounts of ingredients contained in supplements is available at this time. Some supplements may not have the amount of an ingredient that is listed on the label and may not fulfill the health claims made for it.

The use of supplements may increase the intake of some nutrients to doses much higher than recommended. Excessive amounts of some vitamins and minerals may be toxic to the fetus. Vitamin A can cause fetal anomalies when taken in high doses. Large amounts of vitamin A are taken by women using the drug isotretinoin (Accutane) for acne. In addition, high doses of some vitamins or minerals may interfere with ability to use others. If women understand this, they are more likely not to exceed recommended doses.

Water

Water is important during pregnancy for the expanded blood volume and as part of the increased maternal and fetal tissues. Women should drink approximately 8 to 10 cups of fluids each day, with water constituting most of the fluid intake (Erick, 2012). Fluids low in nutrients should be limited because they are filling and replace other more nutritious foods and drinks.

Food Plan

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has developed MyPlate, a food plan which provides a guide for healthy eating for adults and children. Guidelines for pregnancy and lactation are discussed below and summarized in Table 14-5. Pregnant or lactating women can go to the website www.choosemyplate.gov to get an individualized diet plan specifically adapted for them and their needs during pregnancy.

TABLE 14-5

FOOD PLAN FOR PREGNANCY AND LACTATION

| FOOD (EQUIVALENT OF 1 OZ OR 1 CUP) | RECOMMENDED INTAKE FOR PREGNANCY∗ | RECOMMENDED INTAKE FOR LACTATION† |

| Whole grains (1 oz = 1 slice bread, ½ c rice or pasta) | 7-9 oz | 7 oz |

| Vegetables | 3-3½ c | 3 c |

| Fruits | 2 c | 2 c |

| Milk group (1 c milk or yogurt, 1½ oz cheese) | 3 c | 3 c |

| Meat/Beans (1 oz meat/poultry/fish, 1 egg, ¼ c dried beans [cooked], 1 tbsp peanut butter) | 6-6½ oz | 6 oz |

∗Example is for a woman 5 feet, 4 inches tall and weighing 125 lb before pregnancy. Specific food plans for other women can be found at www.choosemyplate.gov.

†Amounts are for exclusive breastfeeding. If formula is also being used, 1 oz less of grains, ½ c less of vegetables, and ½ oz less of meat/beans is recommended.

Data from www.choosemyplate.gov.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree