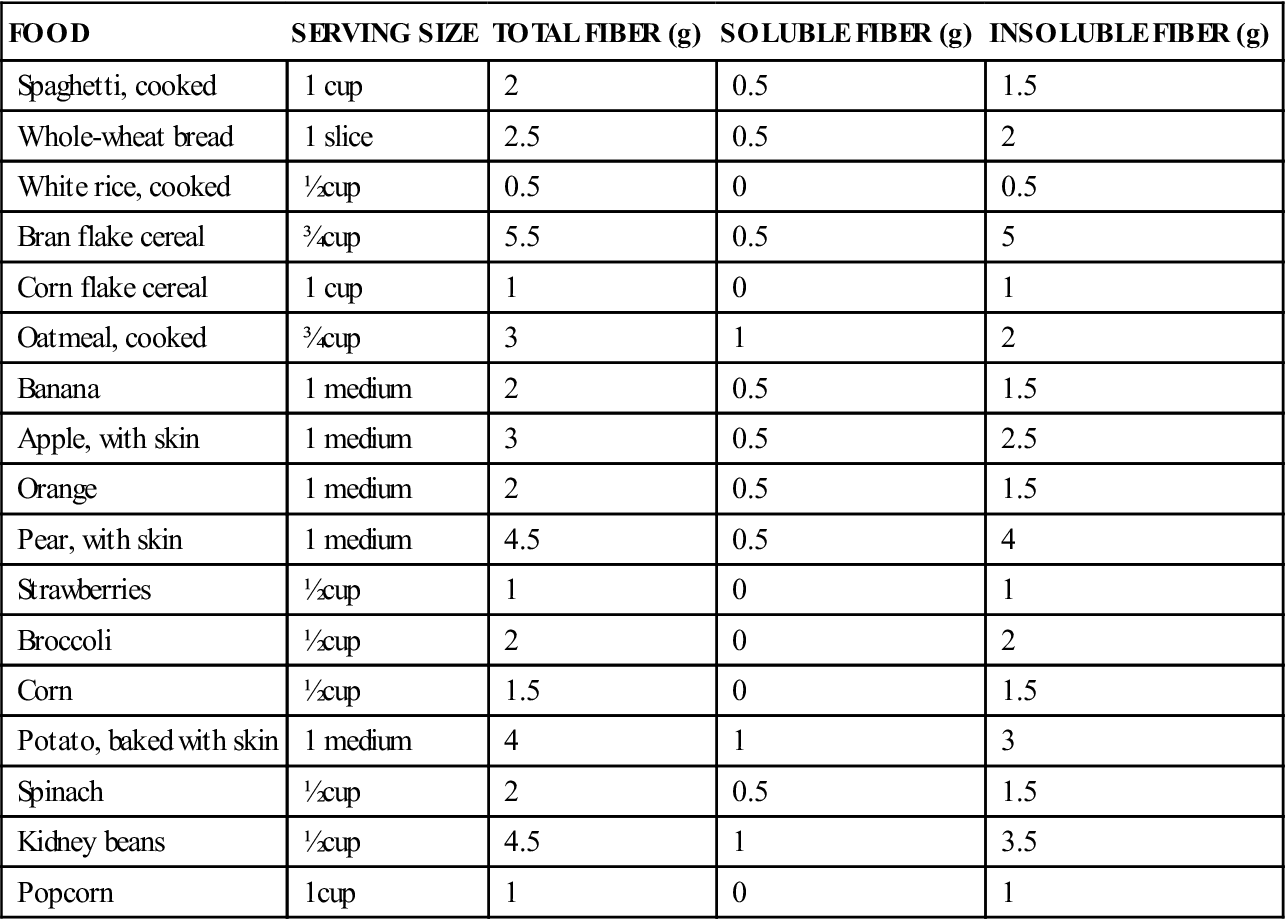

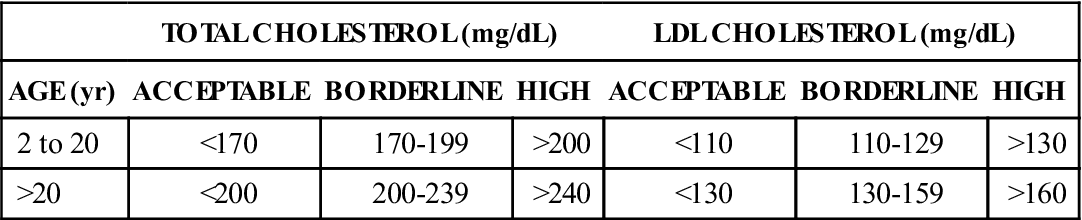

1. Define, spell, and pronounce the terms listed in the vocabulary. 2. Apply critical thinking skills in performing the patient assessment and patient care. 4. Recognize the impact of cultural influences on dietary choices. 5. Classify the types and functions of dietary nutrients. 6. Describe the roles of carbohydrates, fats, protein, and fiber in the daily diet. 7. Explain the function of appropriate amounts of vitamins, minerals, and water in the diet. 9. Implement nutritional assessment techniques. 10. Correlate a patient’s calculated body mass index (BMI) with the risk for diet-related disease. 11. Compare the concepts of therapeutic nutrition. 12. Interpret food labels and their application to a healthy diet. 13. Demonstrate to the patient how to understand nutrition labels on food products. 14. Summarize the causes of eating disorders and obesity and their impact on a patient’s health. 15. Define the concepts of health promotion. 16. Describe the role of the medical assistant in nutrition and health promotion. cholesterol (kuh-les′-tuh-rol) A substance produced by the liver and found in animal fats that can produce fatty deposits or atherosclerotic plaques in blood vessels. deficiencies (di-fi′-shun-sees) Conditions that result with below normal intake of particular substances. diabetes mellitus type 1 A disease in which the beta cells in the pancreas no longer produce insulin. The individual must rely on daily insulin administration to use glucose for energy and prevent complications. diabetes mellitus type 2 A disease in which the body is unable to use glucose for energy as a result either of inadequate insulin production in the pancreas or resistance to insulin on the cellular level. digestion The process of converting food into chemical substances that can be used by the body. diverticulosis (di-vuhr-ti-kyuh-lo′-suhs) The presence of pouchlike herniations through the muscular layer of the colon. hydrogenated (hi-drah′-juh-na-ted) Combined with, treated with, or exposed to hydrogen. macular degeneration A progressive deterioration of the macula of the eye that causes loss of central vision. neural tube defects Any of a group of congenital anomalies involving the brain and spinal column that are caused by failure of the neural tube to close during embryonic development. obesity An excessive accumulation of body fat; defined as a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or higher. osteoporosis (ah-ste-o-puh-ro′-ses) Loss of bone density; lack of calcium intake is a major factor in its development. psyllium (si′-le-um) A grain found in some cereal products, in certain dietary supplements, and in certain bulk fiber laxatives; a water-soluble fiber. registered dietitian (RD) An individual with a minimum of a bachelor’s degree in food and nutrition who is concerned with the maintenance and promotion of health and the treatment of diseases through diet. triglyceride (tri-gli′-suh-ride) A fatty acid and glycerol compound that combines with a protein molecule to form high- or low-density lipoprotein. vertigo Dizziness; a sensation of faintness or an inability to maintain normal balance. Marcia Schwartz, CMA (AAMA), is employed by an internal medicine practice in her hometown. She recognizes that many of the patients seen in the practice have diseases that are influenced by diet and lifestyle factors. She learned about the importance of good nutrition and wellness in her medical assisting program. In addition, Marcia has continued to attend workshops and read about current trends in nutrition, so she is prepared to provide assistance to her patients as directed by the physician. While studying this chapter, think about the following questions: • What should Marcia know about dietary guidelines for fat consumption? • What is the importance of vitamins and nutrients and in what foods can they be found? • How can Marcia educate patients using the new MyPlate Web site? • What are the general guidelines for therapeutic nutrition? • Is it important that Marcia be able to teach patients how to read food labels? Good health is a state of emotional and physical well-being that is determined to a large extent by diet and lifestyle factors. Health promotion and disease prevention practices focus on sound nutrition, regular exercise, avoidance of smoking and tobacco, limited alcohol intake, management of stress, and avoidance of environmental contaminants. We are what we eat, because the food we consume is used to build and repair every part of our bodies. A well-nourished person is also better able to ward off infections. Consequently, a poor diet and risky lifestyle behaviors are directly related to multiple health problems. The physician, the medical assistant, and the registered dietitian (RD) are all closely involved in the nutritive care of a patient. The physician prescribes the diet, and ideally the dietitian instructs the patient in how to follow it. If professional aid is not available, the medical assistant may be asked to discuss the diet with the patient, answer questions, and explain certain aspects of the modifications involved. The patient may hesitate to ask the physician details about a recommended diet, or he or she may call with questions about how to implement the diet after leaving the office. The medical assistant, therefore, frequently is the person to whom the patient turns for answers. You should be able to answer basic questions on healthy nutrition and should have a fundamental knowledge of the diets physicians most often prescribe. People eat the way they do for many reasons. When encouraging patients to make significant changes in their diets, the medical assistant must be sensitive to these reasons. The choices people make about what they eat are greatly influenced by their background and relationships. Every culture, religion, and ethnic group has its own beliefs and practices with regard to food. For example, according to the Hindu religion, eating beef is forbidden. Certain Jewish practices govern the types of foods that are eaten and how they are prepared. Food is more than sustenance; it represents family and celebrations and has an entire psychological component that the medical assistant must recognize in order to care for the individual patient most effectively. The term nutrition refers to all the processes involved in the intake and use of nutrients. Nutrients are the organic and inorganic chemicals in food that supply the energy and raw materials for cellular activities. Nutrients include carbohydrate, fat, protein, vitamins, minerals, and water. Metabolism is the process in which nutrients are used at the cellular level for growth and energy production and excretion of waste. Metabolism occurs in two phases, anabolism and catabolism. Anabolism is the building phase, in which smaller molecules, such as amino acids, are combined to form larger molecules, such as proteins. An example of anabolism is the creation by the liver of glycogen, a stored form of glucose. In this process, many units of glucose are combined to form a more complex glycogen molecule. Catabolism is the breaking-down phase, in which larger molecules are broken down and converted into smaller units, such as when stored glycogen is broken down into glucose molecules for energy. Digestion is a combination of mechanical and chemical processes that occur in the mouth, stomach, and small intestine. These processes result in the breakdown of nutrients into absorbable forms, including amino acids, fatty acids, glycerol, and glucose. Most nutrients are absorbed in the small intestine and then carried by the bloodstream to all parts of the body. The term nutrition also is used to indicate nutritional status, or the condition of the body resulting from the use of nutrients. Dietetics is the practical application of nutritional science to individuals. It is the combined science and art of feeding individuals or groups, given a wide range of economic factors and/or health conditions, according to the principles of nutrition and dietary management. A registered dietitian’s role is the promotion of good health through proper diet and the therapeutic use of diet in the treatment of disease. To nurture life, the nutrients in food must perform one or more of three basic functions in the body: (1) provide a source of fuel or energy, (2) supply material to build and repair tissues, and (3) regulate metabolic processes. Because no one food supplies all the nutrients required, a combination of different foods is necessary to promote health. With a little planning, all the body’s needs can be met by a well-balanced diet. Dietary deficiencies result in undernourishment or malnourishment and may lead to a variety of diseases. Good nutrition is an important part of health promotion for all individuals but especially for pregnant women, young children, and the elderly. The role of diet in supplying energy is crucial to body functions. Every action of the body, whether voluntary or involuntary, requires energy. Even when a person is asleep, the body still needs a source of energy to keep vital organs functioning. Basal metabolism is the amount of energy needed to maintain essential body functions. The basal metabolic rate (BMR) is the amount of energy used by a fasting, resting individual to maintain vital functions. The rate is determined by the amount of oxygen used and is defined in units of heat energy called calories (cal). Because this unit represents a relatively small amount of energy and because metabolism involves much larger amounts of energy, the large calorie (Cal), or kilocalorie (kcal), is commonly used. A kilocalorie is defined as the amount of heat required to raise the temperature of 1 kg of water 1° C. Of the seven food constituents (carbohydrates, proteins, fats, water, minerals, vitamins, and fiber), only carbohydrates, proteins, and fats are capable of furnishing the body with energy. The amount of energy, or kilocalories, a person needs varies according to the individual’s activity level, basal metabolic requirements, and whether disease is present. Most adults age 20 to 40 require 1,800 to 2,200 kcal/day. A patient generally is said to be overweight or underweight depending on how his or her current weight compares with nutritional assessment standards. Obesity is likely to result when more calories are consumed than are expended or because of certain endocrine imbalances. Nutrients can be categorized as those that are a required part of the diet and those that can be anabolized in the body. An essential nutrient cannot be manufactured by the body and therefore must be included in the diet or a deficiency disease occurs. Certain amino acids are examples of essential nutrients. A nonessential nutrient can be created in the body and therefore does not need to be included in the diet; for example, both cholesterol, which is manufactured in the liver, and vitamin D, which is synthesized from exposure to the sun, are nonessential nutrients. Carbohydrates (CHO) are chemical organic compounds composed of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen that are primarily plant products. They are divided into three groups based on the complexity of their molecules: simple sugars (e.g., table sugar, molasses, syrup, honey, candy, baked goods, and milk); complex carbohydrates (starch) (e.g., whole-grain products, cereal, pasta, rice, potatoes, legumes, fruits, vegetables, and seeds); and dietary fiber, which is found in bran, oatmeal, whole-grain breads, beans, fruits, vegetables, seeds, and dried fruits. Each has a function in health and consists of many variations. With the exception of fiber, carbohydrates are easily digested and absorbed into the body. Simple sugars are quickly absorbed, whereas complex carbohydrates must be processed before they can be absorbed in the intestinal tract. Dietary fiber is indigestible and passes through the gastrointestinal tract unchanged. The main function of carbohydrates is to supply fuel for energy and for all basic cellular activities. To meet energy needs, carbohydrate is metabolized at a rate of 4 cal/g. When digested, carbohydrate is converted into glucose, which is carried by the bloodstream to cells that need energy. A small amount of concentrated glucose is stored in the liver and muscles as glycogen. This stored glucose is available to supplement dietary supplies of carbohydrate. As with all nutrients, excess amounts of carbohydrate are converted into fat and stored in the body as adipose tissue. In addition to serving as the body’s primary energy source, carbohydrate also is needed to regulate protein and fat metabolism. As long as sufficient amounts of dietary carbohydrate are available to meet the body’s energy needs, protein and fat are not needed to supply energy. This protein-sparing effect allows protein to be used for its intended purpose—the repair and growth of tissues. Carbohydrate is used for energy with limited production of waste materials, whereas protein and fat metabolism creates byproducts that are challenging for the body to process and excrete. For example, the metabolism of fat for energy results in the production of ketone bodies, which can cause an increase in the acidity of the blood and possibly kidney damage from the excretion of ketones. In addition, the central nervous system (CNS) requires a constant minute-to-minute supply of glucose to function properly. Neurons find it difficult to use fat or protein for energy. Dietary fiber, commonly called roughage, is the portion of a plant that cannot be digested or absorbed. However, fiber’s inability to be digested makes it an important dietary asset. Fiber adds bulk to the intestinal tract that stimulates peristalsis and promotes regular bowel movements. In addition, soluble fiber, which is found in oat bran, peas, beans, certain fruits, and psyllium, lowers blood cholesterol levels, reducing the risk of heart disease. Soluble fiber combines with cholesterol in the intestine and is excreted through the bowel, which prevents the absorption of cholesterol into the bloodstream. Insoluble fiber, which is found in whole grains and beans, promotes regular bowel movements, which prevents constipation and hemorrhoids. It also prevents diverticulosis by stimulating and toning the muscles lining the large intestine, and it is thought to help prevent colon cancer. The recommended daily fiber intake is 20 to 35 g, and 5 to 10 g of this should be soluble fiber. Table 30-1 identifies food sources of both soluble and insoluble fiber. Eating fruit unpeeled and eating raw vegetables can greatly increase the fiber content of the diet. TABLE 30-1 From the American Dietetic Association: Accessed January 12, 2010. Available at www.eatright.org/cps/rde/xchg/SID-5303FFEA-A120B9BE/ada/hs.xsl/nutrition_5440_ENU_HTML.htm. • Fiber-rich fruits, vegetables, and whole grains should be eaten as often as possible. • People should consume 15 g of fiber for every 1,000 calories eaten. Fats are the storage form of fuel used to back up carbohydrates as an available energy source. Fat is a much more concentrated form of fuel, producing 9 cal of energy per gram when metabolized. Dietary fats, or lipids, provide essential fatty acids and are needed for the absorption of the fat-soluble vitamins, A, D, E, and K. Fat gives food flavor and creates a feeling of satiety or satisfaction after eating. Adipose tissue, the stored form of fat in the body, supports and protects vital organs, insulates the body to help in the regulation of body temperature, and plays an important role in protecting nerve fibers and relaying nerve impulses. Lipids are also crucial to cell membrane development. When digested, fats are broken down into fatty acids and glycerol. The main building blocks of fat are fatty acids, which can be either saturated or unsaturated. Unsaturated fatty acids can take on more hydrogen under the proper conditions and therefore are less heavy and less dense. If fatty acids have one unfilled hydrogen bond, the fat is called monounsaturated. Olives and olive oil, peanuts and peanut oil, canola oil, pecans, and avocados contain monounsaturated fats. Polyunsaturated fats, such as safflower, corn, cottonseed, and soy oils, have two or more unfilled hydrogen bonds. Unsaturated fats are found in plants and are usually liquid at room temperature. Monounsaturated fat should be used as frequently as possible to replace saturated fat in the diet. Research on olive oil indicates it may offer some protection against heart disease and breast cancer, and canola oil is another rich source of monounsaturated fatty acids. The chemical structure of a saturated fatty acid contains all the hydrogen possible; these fats, therefore, are denser, heavier, and solid at room temperature. Saturated fats are found in whole milk dairy products, eggs, lard, meat, and hydrogenated fats, such as margarine. Some saturated fats, such as those in soft margarines, are partially hydrogenated. These fats usually are soft at room temperature. Most saturated fats come from animal sources. The main exceptions are coconut and palm oils, which are of plant origin but are exceptionally high in saturated fat. The primary dietary factor associated with high blood cholesterol levels is a high intake of foods high in saturated fat. Even a fat-free food can become high in saturated fat, depending on how it is prepared (e.g., a fat-free potato cooked as french fries). Therefore, we not only need to lower our intake of foods with saturated fat, we also need to be cautious about how foods are prepared. Foods should be grilled, roasted, broiled, baked, or cooked in the microwave rather than fried. Only lean meats should be used, and visible fat should be cut off before eating. Low-fat or fat-free products should be substituted when possible. Some foods high in saturated fat include the following: A triglyceride molecule is created when three fatty acids attach to a molecule of glycerol. This structure is the main storage form of lipids. Triglyceride molecules are transported throughout the body via the bloodstream as lipoproteins. Dietary fats determine the saturation level of triglyceride chains. The total amount of triglycerides in the blood is used as a diagnostic tool for determining a patient’s risk for hypertension and heart disease. The acceptable triglyceride range in men is 40 to 160 mg/dL; for women, it is 35 to 135 mg/dL. Cholesterol is a nonessential nutrient that plays a vital role in metabolic activities. It is synthesized only in animal tissue, so it is not found in plant foods. The primary food sources of cholesterol are egg yolks and organ meats, although all animal sources of food contain cholesterol. As a nonessential nutrient, cholesterol also is manufactured in the body, particularly in the liver. The confusion between “good” and “bad” fat stems from the distinction between the fat in food and the fat in our bodies. The good fats in our diet are monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats. The bad dietary fats are cholesterol, trans fats, and saturated fats. As mentioned, the fat in our bodies is divided into two lipoprotein categories. The good fats, or high-density lipoproteins, carry cholesterol from body tissues or the bloodstream to the liver for metabolism and excretion. The bad fats, or low-density lipoprotein and very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), carry cholesterol to the cells. LDL and VLDL form atherosclerotic plaques on arterial walls, and these plaques frequently result in heart disease, hypertension, and strokes. However, serum LDL levels often can be successfully changed through diet. Using polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fat products reduces total serum cholesterol levels. In addition, using monounsaturated fats (olive, peanut, and canola oils) reduces LDL levels. Aerobic exercise is an important tool for lowering total serum cholesterol levels, increasing HDL levels, and reducing triglycerides. The higher the serum level of HDL, the greater the protection against cardiovascular disease. The normal HDL range is 30 to 80 mg/dL. A level below 40 is considered a major risk for heart disease, whereas a value of 60 or greater is thought to protect against heart disease. Heart experts recommend an LDL level below 100 mg/dL and an HDL level of 60 mg/dL or greater (Table 30-2). TABLE 30-2 Total and Low-Density Lipoprotein (LDL) Cholesterol Level Recommendations Another potential health risk from a high-fat diet is obesity. Too much fat in the diet is deposited in the body as stored adipose tissue. Currently fats make up 35% to 40% of the total calories in the American diet. Nutritionists and epidemiologists believe that reducing dietary fat to 30%, with saturated fat and trans fat making up no more than 10% of calories, would reduce the risks of cancer, atherosclerosis, hypertension, and heart disease. • Keep total fat intake to 20% to 35%, or approximately 17 g of fat per day for a 2,000-calorie diet. • No more than 10% of daily calories should come from saturated and trans fats. • Limit cholesterol to less than 300 mg/day. • Use only lean cuts and smaller portions of meat; trim visible fat. • Substitute poultry and fish for red meat; remove poultry skin before eating. • Avoid adding fat in the cooking process. • Limit intake of organ meats and egg yolks. • Use low-fat or fat-free milk and milk products. • Use low-fat or fat-free products. • Choose liquid monounsaturated oils, such as canola or olive oil. Cholesterol has been high on the list of dietary villains for years and is thought to be a serious contributor to the development of heart disease. Recent studies indicate that the problem may lie not with the cholesterol itself but with the way it reacts with oxygen, or the process of oxidation, in the bloodstream. The normal body process of using oxygen for energy, combined with environmental factors, such as pollution and tobacco smoke, creates free radicals, which can cause cellular damage. Our bodies have developed mechanisms to protect us against oxidizing free radicals through the use of antioxidant vitamins C, E, and beta-carotene, but their amounts are not always sufficient. When enough antioxidants are circulating in the blood, cholesterol is prevented from oxidizing. If the level of antioxidants is insufficient, the opposite is true, and damage to arteries begins. Therefore, in addition to lowering cholesterol, saturated fat, and trans fat intake, increasing dietary intake of antioxidants may prove beneficial in preventing cardiovascular disease. Research indicates that a diet rich in antioxidant vitamins also may be linked to protection against some cancers and macular degeneration. Naturally occurring antioxidants are found in many fruits and vegetables and certain seasonings. Proteins are very large, complex molecules. They are composed of units known as amino acids, which are the materials the body uses to build and repair tissues. Twenty amino acids are necessary for normal growth and maintenance of tissues. Of these, eight are essential amino acids that must be included in the diet because humans do not have the enzymes necessary for their formation. Proteins are classified according to whether they contain all essential amino acids in good proportion. Complete proteins come from animal sources and have a mixture of all eight essential amino acids. Incomplete proteins do not supply the body with all the essential amino acids. These are the vegetable proteins, which must be used in specific combinations because each is missing or extremely low in one or more of the essential amino acids. To prevent the wasting of protein for energy and to permit the creation of needed amino acid compounds, dietary protein must be adequate, the diet must supply essential amino acids, and enough carbohydrate and fat must be consumed to prevent the burning of protein for energy. Fortunately, most foods have a mixture of proteins that supplement one another. Because little, if any, storage of amino acids occurs in the body, it is important that a source of protein be included at each meal. Patients with extensive burns or those with wound healing problems often are prescribed high-protein diets to encourage tissue regeneration. Healthy adult women need approximately 45 g of protein a day, and men need approximately 55 to 60 g. The average North American diet contains twice that amount. Excess protein is metabolized and either converted to glucose, burned as fuel, or stored as fat in adipose tissue. If incomplete proteins are the only source of protein in the diet, a food that is protein deficient in one amino acid should be eaten with one that is high in the same amino acid to get the needed mix of essential amino acids. Vegetarianism has become increasingly popular, and many different forms exist. Some vegetarians consume no red meat but eat fish and poultry. Lacto-ovovegetarians eat primarily vegetable foods but include eggs and/or dairy products in their diets. Lactovegetarians consume milk and milk products in addition to vegetables but no other animal sources of food. Vegans consume no animal proteins at all, relying solely on vegetable foods for protein. Those who eat some animal protein in the form of fish, eggs, and milk generally are not at risk nutritionally. However, vegans must include a variety of vegetable foods to ensure the nutritional adequacy of their diets. To supply sufficient protein, vegetables that complement each other must be eaten together to get the correct proportion of amino acids. This is customarily done in the diets of different cultures. For example, in Mexico, beans are combined with rice, and in Middle Eastern countries, wheat bread is combined with cheese. Tips for vegetarians from the USDA Web site (www.mypyramid.gov) include the following: Vitamins are organic substances that occur in minute quantities in plant and animal tissues; they are needed for specific metabolic processes to proceed normally. Vitamins function as catalysts and help or allow metabolic reactions to proceed. Originally they were lettered or numbered as they were discovered. However, as they have been identified chemically, they have been given more specific names. In many cases their chemical names are as well known as their letter designations. Vitamins are divided into two groups: fat soluble (A, D, E, and K) and water soluble (B complex and C). Some vitamins are nonessential, meaning they can be manufactured in the body. Vitamin A is produced from beta-carotene food sources such as carrots, pumpkin, and sweet potatoes. Ultraviolet light from the sun initiates the production of vitamin D in the skin. Vitamin K is created from intestinal bacteria. Vitamins do not cure an illness other than a health problem that is caused by the lack of a specific vitamin. For example, adding vitamin C to a patient’s diet does not cure bleeding gums unless the condition is specifically caused by a lack of ascorbic acid (the chemical name for vitamin C). It should also be noted that toxic symptoms from excessive ingestion of fat-soluble vitamins can occur, because these vitamins can be stored in adipose tissue. Water-soluble vitamins typically are excreted in the urine. However, a large intake of some water-soluble vitamins may cause adverse effects (Table 30-3). Nutrition experts agree that vitamins provide the greatest benefit when they are obtained through food as part of the diet rather than in supplement form. However, supplements may be needed in the following cases: • Patients showing signs and symptoms of a vitamin or mineral deficiency • Folate for women planning on becoming pregnant or in their childbearing years • Iron and folate for pregnant and lactating women • Calcium for lactose-intolerant individuals • Postsurgical or burn patients, who require more protein and nutrients to grow and repair tissue • Strict vegetarians, who may need vitamins B12 and D, along with iron and zinc

Nutrition and Health Promotion

Learning Objectives

Vocabulary

Scenario

Nutrition and Dietetics

Nutrients

Nutrient Components

Carbohydrates

FOOD

SERVING SIZE

TOTAL FIBER (g)

SOLUBLE FIBER (g)

INSOLUBLE FIBER (g)

Spaghetti, cooked

1 cup

2

0.5

1.5

Whole-wheat bread

1 slice

2.5

0.5

2

White rice, cooked

½ cup

0.5

0

0.5

Bran flake cereal

¾ cup

5.5

0.5

5

Corn flake cereal

1 cup

1

0

1

Oatmeal, cooked

¾ cup

3

1

2

Banana

1 medium

2

0.5

1.5

Apple, with skin

1 medium

3

0.5

2.5

Orange

1 medium

2

0.5

1.5

Pear, with skin

1 medium

4.5

0.5

4

Strawberries

½ cup

1

0

1

Broccoli

½ cup

2

0

2

Corn

½ cup

1.5

0

1.5

Potato, baked with skin

1 medium

4

1

3

Spinach

½ cup

2

0.5

1.5

Kidney beans

½ cup

4.5

1

3.5

Popcorn

1 cup

1

0

1

Recommendations for Carbohydrate Consumption

Fats

Saturated and Unsaturated Fatty Acids.

Foods High in Saturated Fat.

Cholesterol.

TOTAL CHOLESTEROL (mg/dL)

LDL CHOLESTEROL (mg/dL)

AGE (yr)

ACCEPTABLE

BORDERLINE

HIGH

ACCEPTABLE

BORDERLINE

HIGH

2 to 20

<170

170-199

>200

<110

110-129

>130

>20

<200

200-239

>240

<130

130-159

>160

Recommendations for Fat Consumption

Antioxidants.

Proteins

Recommendations for Protein Consumption

Vitamins (Micronutrients)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree