After studying this chapter, students will be able to: • Describe the demographics of professional nursing today. • Identify the broad range of settings in which today’s registered nurses practice. • Discuss emerging practice opportunities for nurses. • Cite similarities and differences among nursing roles in various practice settings. • Explain the roles of advanced practice nurses and the preparation required to assume these roles. To enhance your understanding of this chapter, try the Student Exercises on the Evolve site at http://evolve. elsevier.com/Black/professional. Chapter opening photo from iStockPhoto.com. Welcome to nursing. You are entering this great profession at an exciting, unsettled time, a time of transformation. Writing about “nursing today” poses a challenge, because what is current today may have already changed by the time you are reading this. What does not change, however, is the commitment of nurses to what Rosenberg (1995) referred to as “the care of strangers”—professional caring, learned through focused education and deliberate socialization (Storr, 2010). In other words, you will be taught to think like a nurse and to do well those things that nurses do. You will become a nurse. Every 4 years since 1977, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has conducted a comprehensive appraisal of nursing through the National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses (NSSRN). The most recent survey was conducted in 2012, and data from that survey will be available in 2014. The most current available data are from the 2008 survey, published in 2010 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010). The entire document, The registered nurse population: Findings from the 2008 National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses, is available as a .pdf file in a direct link: http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/rnsurveys/rnsurveyfinal.pdf. The complete report is comprehensive. The following data are just a sample of the findings from this survey to provide you with a thumbnail sketch of nursing today, specifically focusing on the number of nurses in the workforce, as well as their gender, age, race, ethnicity, and educational levels. Registered nurses (RNs) are the largest group of health care providers in the United States. More than 3 million individuals held licenses as RNs in 2008, a 5.3% increase from the 2004 survey. Approximately 445,000 RNs received their first license to practice in the United States and 291,000 RNs allowed their licenses to expire, resulting in a net increase in RNs of 154,000 between 2004 to 2008 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010). The retirement of the older generation of nurses has been long anticipated; these lapses in licensure may indicate that this wave of retirement is occurring. An estimated 2.6 million (85% of) licensed RNs were actively working in nursing, 63% of them full-time. For nurses younger than 50 years old, 90% were employed in nursing either full- or part-time; fewer than half of the nurses older than 65 were working in nursing. A significant percentage of nurses hold two nursing positions. Among those working full-time in nursing, 12% have a second nursing position; 14% of those working part-time in nursing hold a second nursing position (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010). Nursing remains a profession dominated by women; however, the percentage of men in nursing has increased by 50% since 2000 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010). Overall, 7.1% of nurses are men, and 92.9% are women. However, among nurses licensed before 2000, 6.2% were men and 93.8% were women. Of those licensed in 2000 or later, 9.6% are men and 90.4% are women. Figure 1-1 gives a clear picture of the disparity between the overall percentages of women and men in nursing. In 2010, 11.4% of students in entry-level bachelor of science in nursing (BSN) programs were men (American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2012). Male and female RNs were equally likely to have a bachelor’s or higher degree in nursing or nursing-related fields (49.9% and 50.3%, respectively). Men, however, were more likely than women to have a bachelor’s or higher degree in nursing and any nonnursing field (62% vs. 55%). A higher percentage of the men work in hospitals (76% vs. 62%). At 41%, men are over-represented in the advanced practice role of certified registered nurse anesthetists. Among all other job titles held by men, staff nurse and administration have proportional representation, with about 7% of these positions held by men. Nurse practitioners and “other” positions (e.g., consultant, clinical nurse specialist, informatics, researcher) are slightly less proportional, with 6% of these positions held by men. Interestingly, only about 3.8% of instructor positions are held by men. The future of any profession depends on the infusion of youth, and the steady increase in the age of the nursing workforce has been a concern. For the first time in the past 30 years, however, the rate of aging of nurses in the workforce has slowed (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010). This is a result of the increased number of working RNs who are under age 30, which offsets the increasing number of nurses age 60 or older who continue to work. The rise in the number of nurses under age 30 is attributed to the increased number of graduates from bachelor of science in nursing (BSN programs, who tend to be younger than graduates from other types of nursing programs. Since 2005, the average age of graduates from all nursing programs has been 31 years old. BSN graduates, at an average age of 28 years old, are 5 years younger than graduates of associate-degree and diploma (hospital-based) programs, who are on average 33 years old. Racial/ethnic minorities make up 34.4% of the population of the United States today but only 16.8% of the RN population, an underrepresentation by about 50% in 2008 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010) (Figure 1-2). Although still troublesome, the number is an improvement from 2004, when only 12.2% of RNs had racial/ethnic minority backgrounds. The largest disparity between the U.S. general population and the RN population is seen with Hispanics/Latinos of any race. Although this group forms about 15.4% of the U.S. population, they make up only 3.6% of RNs. Black/African American, non-Hispanics also have a significant disparity; now constituting 12.2% of the U.S. population, this group makes up just 5.4% of RNs. The only group that exceeds its representational percentage in the general population is the Asian or Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic group. Composing 4.5% of the general population, this group makes up 5.8% of the RN population, possibly because a substantial number of RNs practicing in the United States received their nursing education in India or the Philippines, thus contributing to their overrepresentation. Despite efforts to recruit and retain racial/ethnic minority women and men in the nursing profession, nursing still has a long way to go before the racial/ethnic composition of the profession more accurately reflects that of the United States as a whole. This situation is slowly improving, however. In a recent report on enrollment and graduation in bachelor’s and graduate programs in nursing, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN, 2010) showed that 26.8% of nursing students in entry-level BSN programs were from minority backgrounds. Nursing has three mechanisms by which you can get basic nursing education to qualify to take the NCLEX®: (1) 4-year education at a college or university conferring a BSN degree; (2) 2-year education at a community college or technical school conferring an associate degree in nursing (ADN); and (3) a diploma in nursing, awarded after the successful completion of a hospital-based program that typically takes 3 years to complete, including prerequisite courses that may be taken at another school. There are rare instances of initial qualification for licensure that occur through military training or master’s or doctoral degrees, but most of these basic nursing education programs are designed for students who have earned undergraduate or graduate degrees previously. Nursing education is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 7. Diploma programs are gradually disappearing, many of which are now affiliated with local community colleges and confer the associate of science degree. Since 2004, only 3.1% of RNs reported receiving a diploma as their entry-level education. The majority of nurses in the United States get their initial nursing education in ADN programs; however, slightly more than 50% of nurses eventually earn a BSN or a master’s or doctoral degree. Many colleges and universities offer BSN programs, often online, to accommodate RNs in practice who want to work toward a BSN degree as a supplement to their basic nursing education at the ADN or diploma level. White, non-Hispanic nurses are less likely to get a BSN or higher degree than are Black/African American, non-Hispanics; Hispanic/Latino, any race; and Asian, non-Hispanic nurses. Figure 1-3 shows the distribution of RNs across levels of initial education. Globalization and the international migration of nurses has resulted in an increase of internationally educated nurses practicing in the United States, up from 3.7% in 2004 to 5.6% in 2008 (Thekdi, Wilson, Xu, 2011). The recruitment of foreign-educated nurses to the United States has been a strategy to expand the nursing workforce in response to the recent nursing shortage. This strategy, however, has been criticized because recruitment of these nurses to the United States may result in shortages in their own countries. Foreign-educated nurses face challenges as they join the workforce in the United States, including speaking English as a second language and problems with their peers who may not perceive them as knowledgeable (Thekdi et al, 2011). Deep cultural differences may further separate the foreign-educated nurses from their American peers. Thekdi and colleagues (2011) noted that foreign-educated nurses may have very different views of gender, authority, power, and age that affect their communication styles. Furthermore, absolute respect for experts and teachers is common among foreign-educated nurses, creating a “permanent barrier” between nurse-managers and managers, and foreign-educated nurses. Sigma Theta Tau International (STTI) (2005) published a position paper on international nurse migration, recognizing the autonomy of nurses in making decisions for themselves about where to live and work, and noting that “push/pull” factors shape nurse migration. Push factors include poor compensation and working conditions, political instability, and lack of opportunities for career development that drive (push) a nurse to seek employment in another country. Factors that pull nurses to emigrate include opportunities for a better quality of life, personal safety, and professional incentives such as increased pay, better working conditions, and career development. STTI called for further exploration of the issue with a focus on identifying “solutions that do not promote one nation’s health at the expense of another” (p. 2). Furthermore, STTI endorsed the International Council of Nurses position in calling for a regulated recruitment process based on ethical principles that deter exploitation of foreign-educated nurses and reinforce sound employment policies (p. 4). Ambulatory care settings, such as physician-based practices, nurse-based practices, and free-standing emergency and surgical centers accounted for 10.5%, the second largest segment of the nurse workforce. Public and community health accounted for 7.8% of employed nurses, and an additional 6.4% worked in home health. Nursing homes or extended care facilities employed 5.3% of nurses in the workforce. The remainder of employed RNs worked in settings such as schools of nursing; nursing associations; local, state, or federal governmental agencies; state boards of nursing; or insurance companies (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010, pp. 3-9). Nurses have much to consider in deciding where to practice. Some settings will not be immediately open to new nurses because they require additional educational preparation. Importantly, nurses entering the workforce need to consider their special talents, likes, and dislikes—neither the nurse nor patients benefit when a nurse is working with a population for which he or she has little affinity. A nurse who loves children may not feel at ease in caring for elderly patients; a nurse with excellent communication skills may find that a postanesthesia care unit does not allow the formation of professional relationships with patients that this nurse might enjoy in a psychiatric setting. Nursing school offers the chance to experience a wide variety of settings with diverse patient populations. At the end of your studies, you may be surprised at the skills you have developed and by which populations appeal to you (Figure 1-4). Salaries and responsibilities increase at the upper levels of the clinical ladder. The clinical ladder concept benefits nurses by allowing them to advance while still working directly with patients. Hospitals also benefit by retaining experienced clinical nurses in direct patient care, thus improving the quality of nursing care throughout the hospital. Research has demonstrated that patient outcomes are more positive for patients cared for by bachelor’s- or higher- degree–prepared RNs. Linda Aiken, PhD, RN, FAAN is a leader in nursing who has conducted important research documenting the positive impact of adequate RN staffing on patient outcomes. A decade ago, Aiken, Clarke, Cheung, and others (2003) published a groundbreaking study in which they found that patients on surgical units with more BSN-prepared nurses had fewer complications than patients on units with fewer BSN nurses. Aiken has published widely on nurse staffing and safety since publishing this landmark study. More recently, Aiken, Sloane, Cimiotti, and colleagues (2010) reported on a comparison of nurse and patient outcomes among hospitals in California, which has state-mandated nurse-to-patient ratios, and in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, neither of which has state-mandated nurse-to-patient ratios. See the Evidence-Based Practice Note for a description of these studies.

Nursing today: A time of transformation

Status of nursing in the United States

Numbers

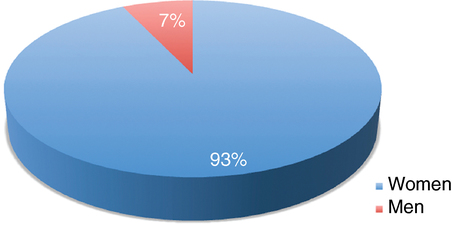

Gender

Age

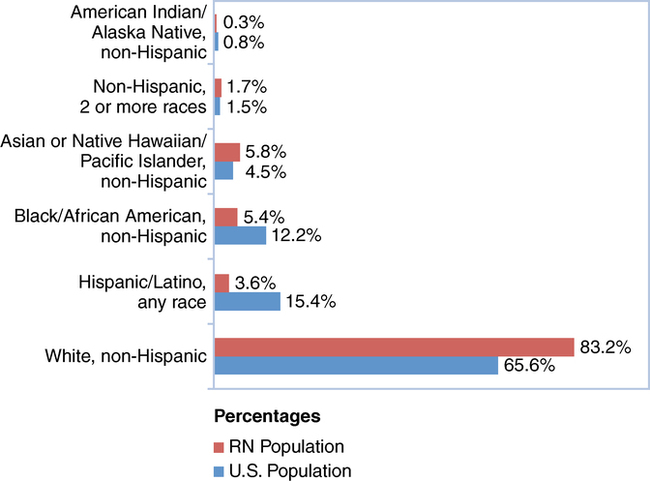

Race and ethnicity

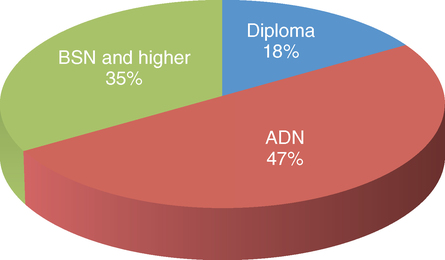

Education

Employment opportunities for nurses

Hospital-based nursing

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree