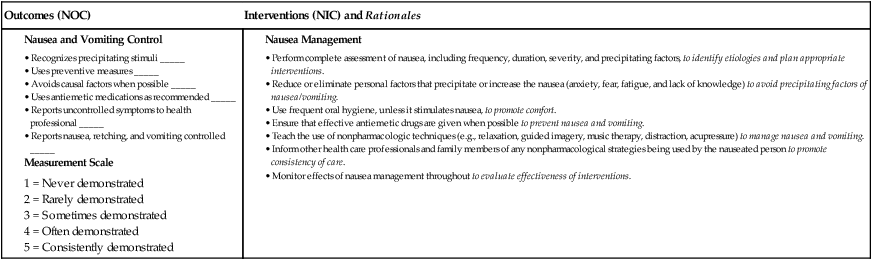

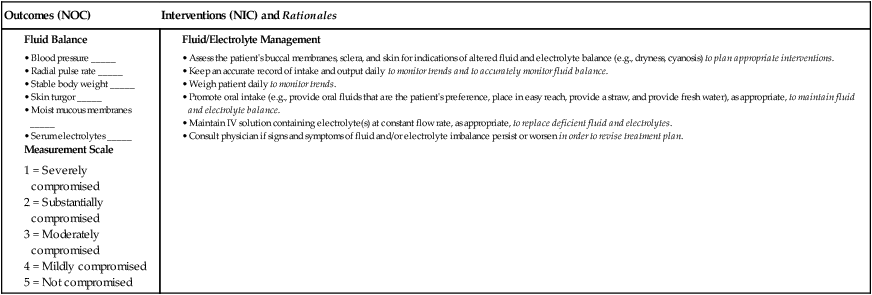

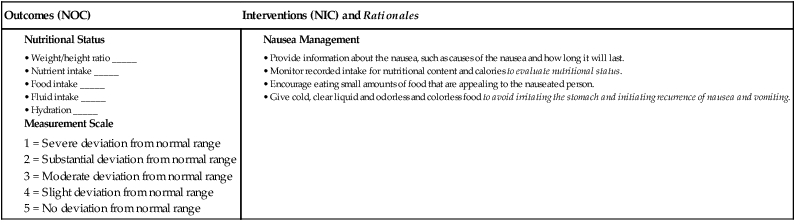

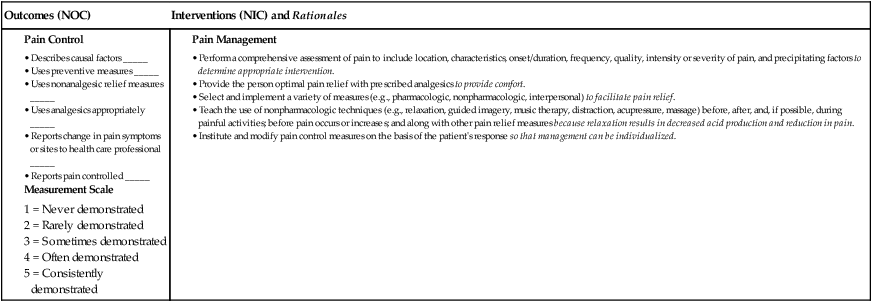

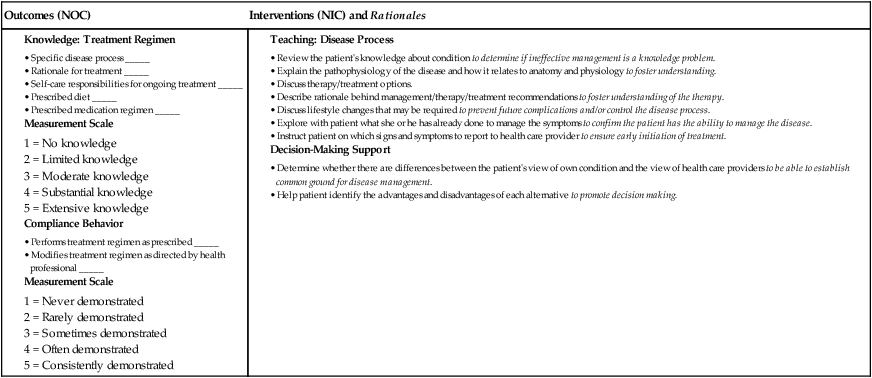

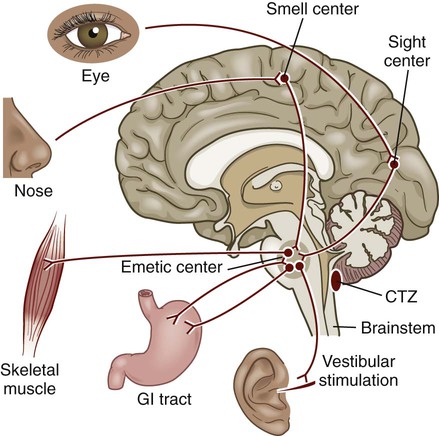

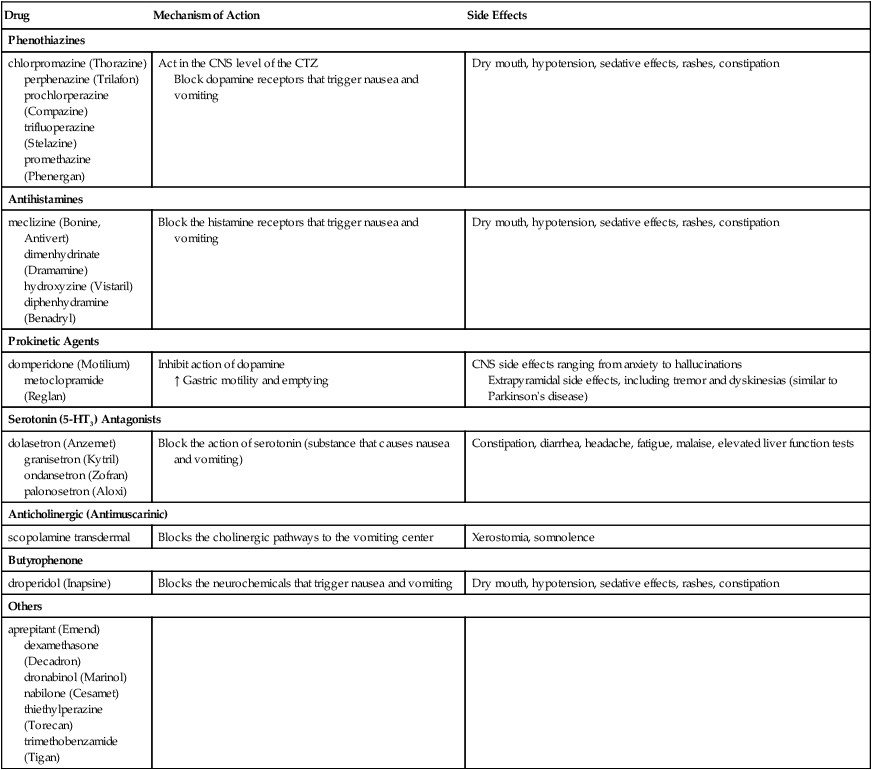

Chapter 42 1. Describe the etiology, complications, collaborative care, and nursing management of nausea and vomiting. 2. Describe the etiology, clinical manifestations, and treatment of common oral inflammations and infections. 3. Describe the etiology, clinical manifestations, complications, collaborative care, and nursing management of oral cancer. 4. Explain the types, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, complications, and collaborative care (including surgical therapy and nursing management) of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and hiatal hernia. 5. Describe the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, complications, and collaborative care of esophageal cancer, diverticula, achalasia, and esophageal strictures. 6. Differentiate between acute and chronic gastritis, including the etiology, pathophysiology, collaborative care, and nursing management. 7. Compare and contrast gastric and duodenal ulcers, including the etiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, complications, collaborative care, and nursing management. 8. Describe the clinical manifestations, collaborative care, and nursing management of stomach cancer. 9. Explain the common etiologies, clinical manifestations, collaborative care, and nursing management of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. 10. Identify common types of foodborne illnesses and nursing responsibilities related to food poisoning. A vomiting center in the brainstem coordinates the multiple components involved in vomiting. This center receives input from various stimuli. Neural impulses reach the vomiting center via afferent pathways through branches of the autonomic nervous system. Receptors for these afferent fibers are located in the GI tract, kidneys, heart, and uterus. When stimulated, these receptors relay information to the vomiting center, which then initiates the vomiting reflex (Fig. 42-1). The goals of collaborative care are to determine and treat the underlying cause of the nausea and vomiting and to provide symptomatic relief. Assess the patient for precipitating factors, and describe the contents of the emesis. Women are more likely to suffer from nausea and vomiting associated with surgical procedures and motion sickness.1 The use of drugs (Table 42-1) in the treatment of nausea and vomiting depends on the cause of the problem. Because the cause cannot always be readily determined, use drugs with caution. Using antiemetics before determining the cause can mask the underlying disease process and delay diagnosis and treatment. Many antiemetic drugs act in the CNS via the CTZ to block the neurochemicals that trigger nausea and vomiting. TABLE 42-1 DRUG THERAPY The serotonin (5-HT3) receptor antagonists are effective in reducing cancer chemotherapy–induced vomiting caused by delayed gastric emptying and also the nausea and vomiting related to migraine headache and anxiety.2 5-HT3 antagonists are also used in prevention and treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Dexamethasone (Decadron) is used in the management of both acute and delayed cancer chemotherapy–induced emesis, usually in combination with other antiemetics such as ondansetron (Zofran). Aprepitant (Emend), a substance P/neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist, is used for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced and postoperative nausea and vomiting. For some patients, acupressure or acupuncture at specific points is effective in reducing postoperative nausea and vomiting.3 Some patients use herbs such as ginger and peppermint oil. Relaxation breathing exercises, changes in body position, or exercise may be helpful for some patients. Each patient with a history of prolonged and persistent nausea or vomiting requires a thorough nursing assessment before you develop a specific plan of care. Although numerous conditions are associated with nausea and vomiting, you should have a basic understanding of the more common conditions and be able to identify the patient who is at high risk. Knowledge of the physiologic mechanisms involved in nausea and vomiting is important in the assessment process. Table 42-2 presents subjective and objective data to be obtained from a patient with nausea and vomiting. TABLE 42-2 NURSING ASSESSMENT

Nursing Management

Upper Gastrointestinal Problems

Nausea and Vomiting

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Collaborative Care

Drug Therapy.

Nausea and Vomiting

Drug

Mechanism of Action

Side Effects

Phenothiazines

chlorpromazine (Thorazine)

perphenazine (Trilafon)

prochlorperazine (Compazine)

trifluoperazine (Stelazine)

promethazine (Phenergan)

Act in the CNS level of the CTZ

Block dopamine receptors that trigger nausea and vomiting

Dry mouth, hypotension, sedative effects, rashes, constipation

Antihistamines

meclizine (Bonine, Antivert)

dimenhydrinate (Dramamine)

hydroxyzine (Vistaril)

diphenhydramine (Benadryl)

Block the histamine receptors that trigger nausea and vomiting

Dry mouth, hypotension, sedative effects, rashes, constipation

Prokinetic Agents

domperidone (Motilium)

metoclopramide (Reglan)

Inhibit action of dopamine

↑ Gastric motility and emptying

CNS side effects ranging from anxiety to hallucinations

Extrapyramidal side effects, including tremor and dyskinesias (similar to Parkinson’s disease)

Serotonin (5-HT3) Antagonists

dolasetron (Anzemet)

granisetron (Kytril)

ondansetron (Zofran)

palonosetron (Aloxi)

Block the action of serotonin (substance that causes nausea and vomiting)

Constipation, diarrhea, headache, fatigue, malaise, elevated liver function tests

Anticholinergic (Antimuscarinic)

scopolamine transdermal

Blocks the cholinergic pathways to the vomiting center

Xerostomia, somnolence

Butyrophenone

droperidol (Inapsine)

Blocks the neurochemicals that trigger nausea and vomiting

Dry mouth, hypotension, sedative effects, rashes, constipation

Others

aprepitant (Emend)

dexamethasone (Decadron)

dronabinol (Marinol)

nabilone (Cesamet)

thiethylperazine (Torecan)

trimethobenzamide (Tigan)

Nondrug Therapy.

Nursing Management Nausea and Vomiting

Nursing Assessment

Nausea and Vomiting