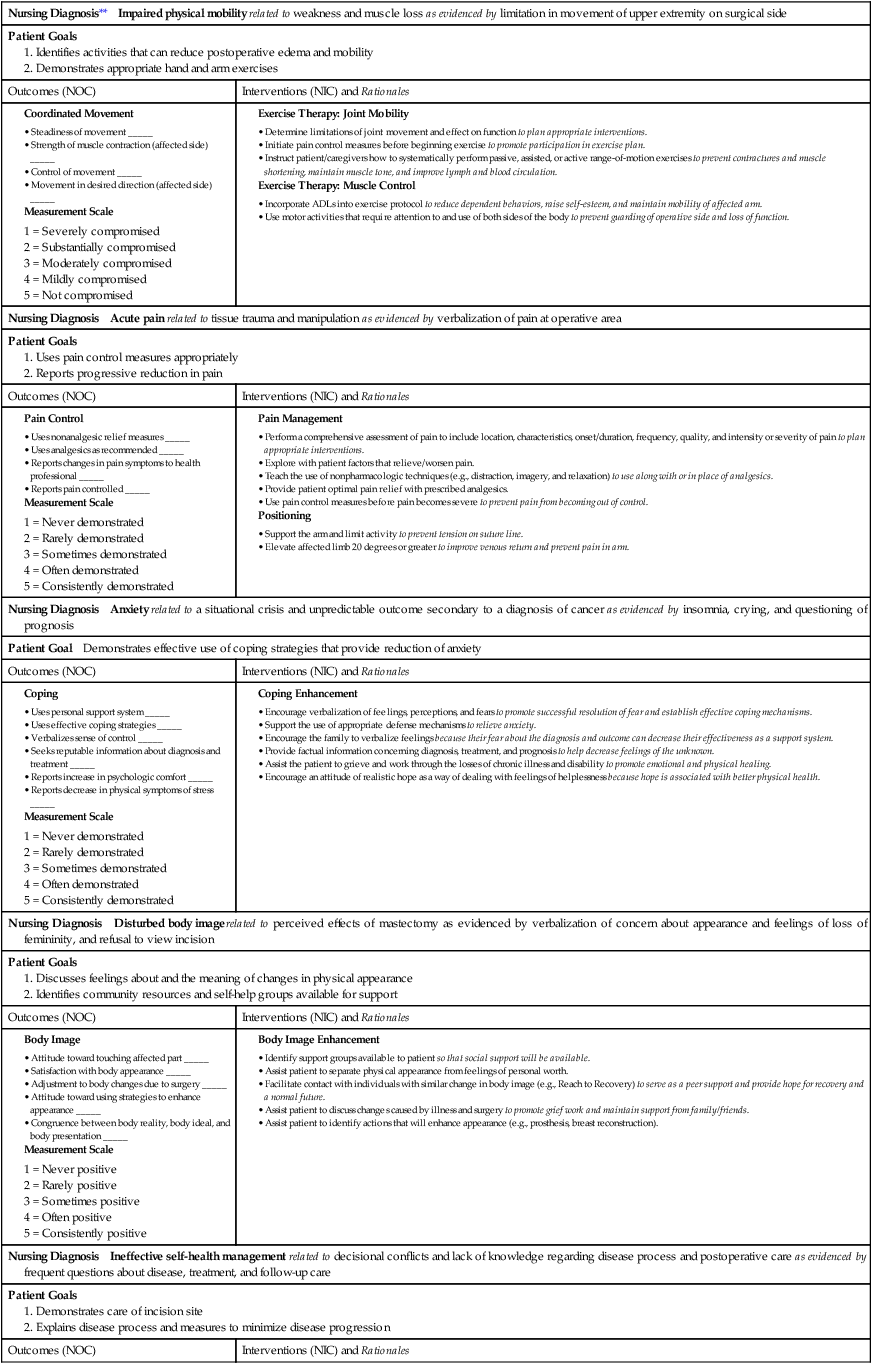

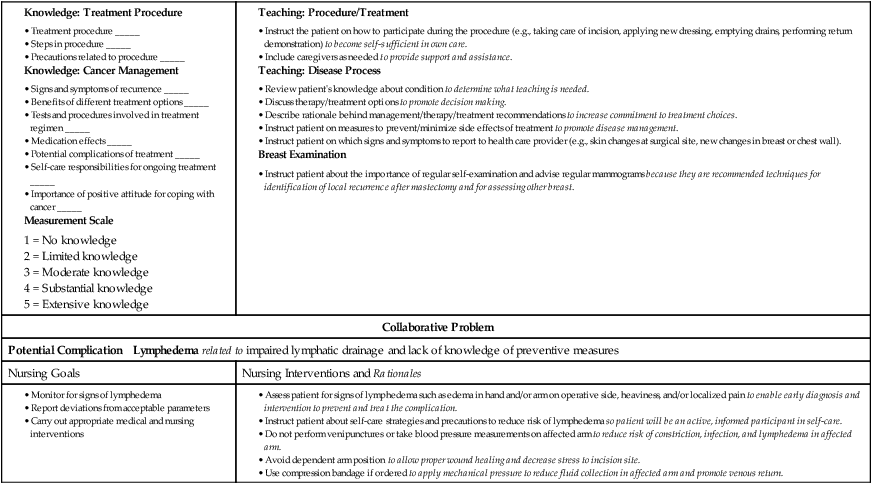

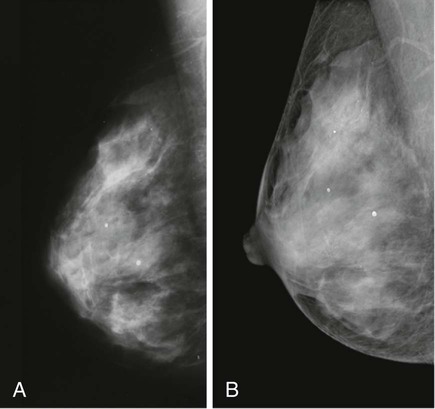

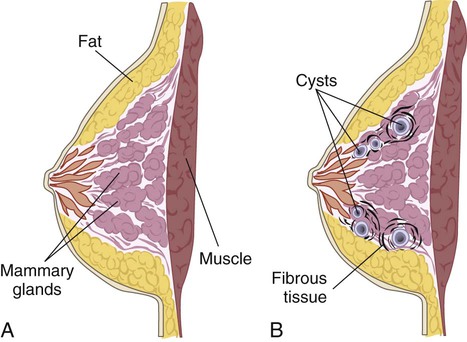

Chapter 52 1. Summarize screening guidelines for the early detection of breast cancer. 2. Describe accurate clinical breast examination techniques, including inspection and palpation. 3. Explain the types, causes, clinical manifestations, and nursing and collaborative management of common benign breast disorders. 4. Assess the risk factors for breast cancer. 5. Describe the pathophysiology and clinical manifestations of breast cancer. 6. Describe the collaborative care and nursing management of breast cancer. 7. Specify the physical and psychologic preoperative and postoperative aspects of nursing management for the patient undergoing a mastectomy. 8. Explain the indications for reconstructive breast surgery, types and complications of reconstructive breast surgery, and nursing management after reconstructive breast surgery. The most frequently encountered breast disorders in women are fibrocystic changes, fibroadenoma, intraductal papilloma, ductal ectasia, and breast cancer. In a woman’s lifetime there is a 1 in 8 chance she will be diagnosed with breast cancer.1 In men, gynecomastia is the most common breast disorder. Screening guidelines for the early detection of breast cancer include the following:2–5 • Yearly mammograms starting at age 40 and continuing for as long as a woman is in good health. A controversial recommended change is that women at normal risk for breast cancer should begin annual screening at age 50 and stop screening at age 75.6 • Clinical breast examination (CBE) preferably at least every 3 years for women in their 20s and 30s, and every year for women beginning at age 40.7 • Women should report any breast changes promptly to their health care provider. Breast self-examination (BSE) is an option for women starting at age 20. • Women at increased risk (family history, genetic link, past breast cancer) should talk with their health care provider about the benefits and limitations of starting mammography screening earlier, having additional tests (e.g., breast ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]), or having more frequent examinations. In recent years there has been some controversy regarding the value of BSE and its role in reducing mortality rates from breast cancer in women. While the benefit of BSE in reducing breast cancer deaths continues to be reviewed, BSE remains a useful technique in helping women develop awareness of how their breasts normally look and feel. Teach women beginning at age 20 the benefits and limitations of BSE and the importance of reporting breast changes (e.g., nipple discharge, a lump) to their health care provider.8 When teaching the woman about BSE, include information related to potential benefits, limitations, and harm (chance of a false-positive test result). Allow time for questions about the procedure and a return demonstration. At every periodic health examination, ask the woman who is performing BSE to demonstrate her technique. For women who choose to do BSE, the technique has recently been revised (Fig. 52-1). Several techniques can be used to screen for breast disease or to help diagnose a suspicious physical finding. Mammography is a method used to visualize the breast’s internal structure using x-rays (Fig. 52-2). This generally well-tolerated procedure can detect suspicious lumps that cannot be felt. Mammography has significantly improved the early and accurate detection of breast malignancies. Improved imaging technology has also reduced the radiation dose from mammography. Digital mammography is a technique in which x-ray images are digitally coded into a computer (see Fig. 52-2). It is not clear whether mammogram interpretation has improved with the aid of a computer. The associated costs of using computer-aided detection may also outweigh the benefits.9 Calcifications are the most easily recognized mammogram abnormality (see Fig. 52-2). These deposits of calcium crystals form in the breast for many reasons, such as inflammation, trauma, and aging. Although most calcifications are benign, they may also be associated with preinvasive cancer. Mastalgia (breast pain) is the most common breast-related complaint in women.10 The most common form is cyclic mastalgia, which coincides with the menstrual cycle. It is described as diffuse breast tenderness or heaviness. Breast pain may last 2 or 3 days or most of the month. The pain is related to hormonal sensitivity. The symptoms often decrease with menopause. Mastitis is an inflammatory condition of the breast that occurs most frequently in lactating women (Table 52-1). Lactational mastitis manifests as a localized area that is erythematous, painful, and tender to palpation. Fever is often present. The infection develops when organisms (usually staphylococci) gain access to the breast through a cracked nipple. In its early stages, mastitis can be cured with antibiotics. Breastfeeding should continue unless an abscess is forming or purulent drainage is noted. The mother may wish to use a nipple shield or to hand-express milk from the involved breast until the pain subsides. The woman should see her health care provider promptly to begin a course of antibiotic therapy. Any breast that remains red, tender, and not responsive to antibiotics requires follow-up care and evaluation for inflammatory breast cancer.11 TABLE 52-1 *This list is not inclusive; other benign breast disorders are discussed in the text. Fibrocystic changes in the breast are a benign condition characterized by changes in breast tissue12 (Fig. 52-3). The changes include the development of excess fibrous tissue, hyperplasia of the epithelial lining of the mammary ducts, proliferation of mammary ducts, and cyst formation. Fibrocystic changes are thought to be due to a heightened responsiveness of breast tissue to circulating estrogen and progesterone. These changes produce pain related to nerve irritation from edema in the connective tissue and to fibrosis that pinches the nerve. Fibrocystic changes are the most common breast disorder. Manifestations of fibrocystic breast changes include one or more palpable lumps that are often round, well delineated, and freely movable within the breast (see Table 52-1). Discomfort ranging from tenderness to pain may also occur. The lump is usually observed to increase in size and perhaps in tenderness before menstruation. Cysts may enlarge or shrink rapidly. Nipple discharge associated with fibrocystic breasts is often milky, watery-milky, yellow, or green. Secretions can also be serous, grossly bloody, or brown to green.13 These secretions may be caused by either benign or malignant disease. A cytology slide may be made of the secretion to determine the specific disease. Diseases associated with nipple discharge include malignancies, cystic disease, intraductal papilloma, and ductal ectasia. Treatment depends on identification of the cause. In most cases, nipple discharge is not related to malignancy. Gynecomastia may also be a manifestation of other problems. It is seen in developmental abnormalities of the male reproductive organs. It may also accompany diseases such as testicular tumors, adrenal cancer, pituitary adenomas, hyperthyroidism, and liver disease.14 Gynecomastia may occur as a side effect of drug therapy, particularly with estrogens and androgens, digitalis, isoniazid (INH), ranitidine (Zantac), and spironolactone (Aldactone). The use of heroin and marijuana can also cause gynecomastia. Breast cancer is the most common malignancy in American women except for skin cancer. It is second only to lung cancer as the leading cause of death from cancer in women. In the United States more than 230,480 new cases of invasive breast cancer and more than 57,650 cases of in situ breast cancer are diagnosed annually.1 About 2140 of those new cases are diagnosed in men. Approximately 39,920 deaths (39,510 women and 410 men) occur each year related to breast cancer. The incidence of breast cancer is slowly decreasing, with a slight drop in the number of deaths related to breast cancer. This decline may be the result of the decreased use of hormone therapy after menopause.2 Approximately 2.6 million women are alive in the United States today who are breast cancer survivors. Patients diagnosed with localized breast cancer with no axillary node involvement have a 5-year survival rate of 98%. Conversely, only 23% of patients diagnosed with advanced-stage breast cancer with metastases to distant sites will survive 5 years or more.1,2 Although the etiology is not completely understood, a number of risk factors are related to breast cancer (Table 52-2). Risk factors appear to be cumulative and interacting. Therefore the presence of multiple risk factors may greatly increase the overall risk, especially for people with a positive family history. TABLE 52-2 RISK FACTORS FOR BREAST CANCER Hormonal regulation of the breast is related to the development of breast cancer, but the mechanisms are poorly understood. The hormones estrogen and progesterone may act as tumor promoters to stimulate breast cancer growth if malignant changes in the cells have already occurred. The Women’s Health Initiative study showed that the use of combined hormone therapy (estrogen plus progesterone) increases the risk of breast cancer and also the risk of having a larger, more advanced breast cancer at diagnosis.15 The use of estrogen therapy alone for longer than 10 years (for women with a prior hysterectomy) increases a woman’s long-term risk for breast cancer. A link may exist between recent oral contraceptive use and increased risk of breast cancer for younger women.16 Modifiable risk factors include excess weight gain during adulthood, sedentary lifestyle, smoking, dietary fat intake, obesity, and alcohol intake.10 Environmental factors such as radiation exposure may also play a role. Family history of breast cancer is an important risk factor, especially if the involved family member also had ovarian cancer, was premenopausal, had bilateral breast cancer, or is a first-degree relative (i.e., mother, sister, daughter). Having any first-degree relative with breast cancer increases a woman’s risk of breast cancer 1.5 to 3 times, depending on age. A breast cancer risk assessment tool for health care providers is available through the National Cancer Institute (see Resources at the end of this chapter). About 5% to 10% of all breast cancers are hereditary. This means that specific genetic abnormalities that contribute to the development of breast cancer have been inherited (passed from parent to child). Most inherited cases of breast cancer are associated with mutations in two genes: BRCA1 and BRCA2 (BRCA stands for BReast CAncer). Everyone has BRCA genes. The BRCA1 gene, located on chromosome 17, is a tumor suppressor gene that inhibits tumor development when functioning normally. Women who have BRCA1 mutations have a 40% to 80% lifetime chance of developing breast cancer. The BRCA2 gene, located on chromosome 11, is another tumor suppressor gene. Women with a mutation of this gene have a similar risk of breast cancer. Mutations in BRCA genes may cause as many as 10% to 40% of all inherited breast cancers. As many as 1 in 200 to 400 women in the United States may be carriers for these genetic abnormalities. Women with BRCA mutations are also at higher risk for developing ovarian, colon, pancreatic, and uterine cancers.17

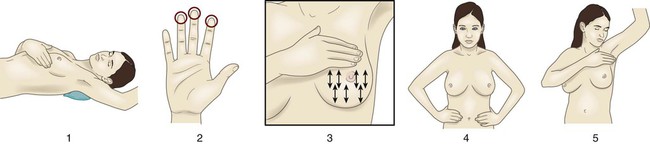

Nursing Management

Breast Disorders

Assessment of Breast Disorders

Breast Cancer Screening Guidelines

Diagnostic Studies

Radiologic Studies.

Benign Breast Disorders

Mastalgia

Breast Infections

Mastitis

Disorder

Risk Factors

Clinical Manifestations

Lactational mastitis

Occurs in up to 10% of postpartum lactating mothers (both primipara and multipara), usually 2-4 wk after birth.

Warm to touch, indurated, painful, often unilateral, most commonly caused by Staphylococcus aureus.

Fibrocystic changes

Most common between ages 35 and 50.

Not usually discrete masses—nodularity instead. Usually accompanied by cyclic pain and tenderness. Mass(es) often cyclic in occurrence (movable, soft).

Cysts

Most common over age 35. Incidence decreases after menopause. Develop in one out of every 14 women.

Palpable fluid-filled mass (movable, soft). Multiple cysts can occur and recur. Rarely associated with breast cancer.

Fibroadenoma

Commonly occurs in 10% of all women ages 15-40.

Palpable mass (firm, movable), usually 2-3 cm in size, rarely associated with breast cancer.

Fat necrosis

Many women report previous history of trauma to breast.

Usually a hard, tender, mobile, indurated mass with irregular borders.

Ductal ectasia

Perimenopausal woman—most common in women in their 50s, previous lactation, inverted nipples.

Fixation of nipple, usually accompanied by nipple discharge of thick gray material. Often associated with breast pain.

Fibrocystic Changes

Nursing and Collaborative Management Fibrocystic Changes

Nipple Discharge

Gynecomastia in Men

Breast Cancer

Etiology and Risk Factors

Risk Factor

Comments

Female

Women account for 99% of breast cancer cases.

Age ≥50 yr

Majority of breast cancers are found in postmenopausal women. After age 60, increase in incidence.

Hormone use

Use of estrogen and/or progesterone as hormone therapy, especially in postmenopausal women.

Family history

Breast cancer in a first-degree relative, particularly when premenopausal or bilateral, increases risk.

Genetic factors

Gene mutations (BRCA1 or BRCA2) play a role in 5%-10% of breast cancer cases.

Personal history of breast cancer, colon cancer, endometrial cancer, ovarian cancer

Personal history significantly increases risk of breast cancer, risk of cancer in other breast, and recurrence.

Early menarche (before age 12), late menopause (after age 55)

A long menstrual history increases the risk of breast cancer.

First full-term pregnancy after age 30, nulliparity

Prolonged exposure to unopposed estrogen increases risk for breast cancer.

Benign breast disease with atypical epithelial hyperplasia, lobular carcinoma in situ

Atypical changes in breast biopsy increase the risk of breast cancer.

Dense breast tissue

Mammograms harder to read and interpret. Dense tissue may be associated with more aggressive tumors.

Weight gain and obesity after menopause

Fat cells store estrogen, which increases the likelihood of developing breast cancer.

Exposure to ionizing radiation

Radiation damages DNA (e.g., prior treatment for Hodgkin’s lymphoma).

Alcohol consumption

Women who drink ≥1 alcoholic beverage per day have an increased risk of breast cancer.

Physical inactivity

Breast cancer risk is decreased in physically active women.

Risk Factors for Women.

![]() Genetic Link

Genetic Link

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nursing Management: Breast Disorders

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access