Nursing Diagnosis

Objectives

• Discuss the purposes of using nursing diagnosis in practice.

• Differentiate among a nursing diagnosis, medical diagnosis, and collaborative problem.

• Discuss the relationship of critical thinking to the nursing diagnostic process.

• Describe the steps of the nursing diagnostic process.

• Explain how defining characteristics and the etiological process individualize a nursing diagnosis.

• Describe sources of diagnostic errors.

Key Terms

Actual nursing diagnosis, p. 227

Clinical criterion, p. 226

Collaborative problem, p. 222

Data cluster, p. 226

Defining characteristics, p. 226

Diagnostic label, p. 228

Etiology, p. 229

Health promotion nursing diagnosis, p. 228

Medical diagnosis, p. 222

NANDA International (NANDA-I), p. 223

Nursing diagnosis, p. 222

Related factor, p. 227

Risk nursing diagnosis, p. 228

![]()

During the nursing assessment process (see Chapter 16) a nurse gathers the information needed to make diagnostic conclusions about patient care. A diagnosis is a clinical judgment based on information. You review information collected about a patient, see cues and patterns in the data, and identify the patient’s specific health care problems. Some of the conclusions lead to identifying nursing diagnoses, whereas others do not. Diagnostic conclusions include problems treated primarily by nurses (nursing diagnoses) and those requiring treatment by several disciplines (collaborative problems). Together nursing diagnoses and collaborative problems represent the range of patient conditions that require nursing care (Carpenito-Moyet, 2009).

When physicians refer to commonly accepted medical diagnoses such as diabetes mellitus or osteoarthritis, they all know the meaning of the diagnoses and the standard approaches for treatment. A medical diagnosis is the identification of a disease condition based on a specific evaluation of physical signs, symptoms, the patient’s medical history and the results of diagnostic tests and procedures. Physicians are licensed to treat diseases and conditions described in medical diagnostic statements.

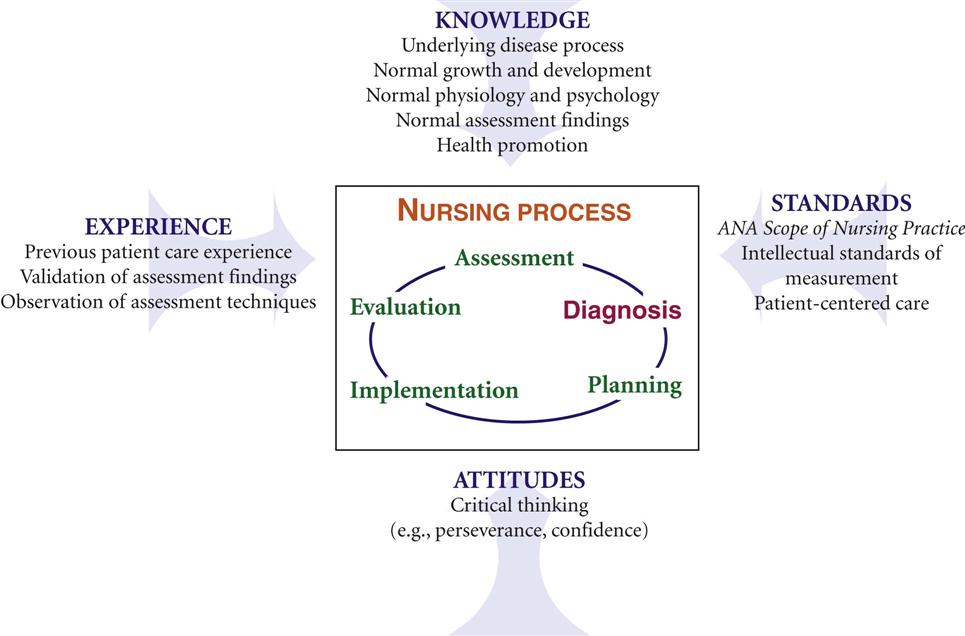

Nursing has a similar diagnostic language. Nursing diagnosis, the second step of the nursing process (Fig. 17-1), classifies health problems within the domain of nursing. A nursing diagnosis such as acute pain or nausea is a clinical judgment about individual, family, or community responses to actual and potential health problems or life processes that the nurse is licensed and competent to treat (NANDA International, 2012). What makes the nursing diagnostic process unique is having patients involved, when possible, in the process.

A collaborative problem is an actual or potential physiological complication that nurses monitor to detect the onset of changes in a patient’s status (Carpenito-Moyet, 2009). When collaborative problems develop, nurses intervene in collaboration with personnel from other health care disciplines. Nurses manage collaborative problems such as hemorrhage, infection, and paralysis using medical, nursing, and allied health (e.g., physical therapy) interventions. For example, a patient with a surgical wound is at risk for developing an infection; thus a physician prescribes antibiotics. The nurse monitors the patient for fever and other signs of infection and implements appropriate wound care measures. A dietitian recommends a therapeutic diet high in protein and nutrients to promote wound healing.

Selecting the correct nursing diagnosis on the basis of an assessment involves diagnostic expertise (i.e., being able to make quick and accurate conclusions from patient data) (Cho, Staggers, and Park, 2010). This is essential because accurate diagnosis of patient problems ensures that you select more effective and efficient nursing interventions. Diagnostic expertise improves with time. Consider the case study involving Mr. Jacobs and his nurse, Tonya Moore.

During her assessment Tonya gathers information suggesting that Mr. Jacobs possibly has a number of health problems. The data about Mr. Jacobs show patterns in four areas: comfort, requesting information about postoperative care, mobility restriction, and worries about his future and his relationship with Mrs. Jacobs. Selecting specific diagnostic labels for these problem areas allows Tonya to develop a relevant and appropriate plan of care. For example, with respect to Mr. Jacobs’ request for information, there are two accepted nursing diagnostic labels for problems related to knowledge: deficient knowledge and readiness for enhanced knowledge. Knowing the difference between these two diagnoses and identifying which one applies to Mr. Jacobs is key to selecting the right type of interventions for his problem. A physician needs to rule out rheumatoid arthritis versus osteoarthritis to be sure that a patient receives the right form of medical treatment. Tonya analyzes her information about Mr. Jacobs and identifies the factors that show the pattern that fits a specific diagnosis. This means that Tonya considers that the patient has no knowledge about or experience with postoperative wound care and freely asks questions. Tonya knows that these factors are defining characteristics that allow her to make an accurate nursing diagnosis.

History of Nursing Diagnosis

Nursing diagnosis was first introduced in the nursing literature in 1950 (McFarland and McFarlane, 1989). Fry (1953) proposed the formulation of nursing diagnoses and an individualized nursing care plan to make nursing more creative. This emphasized the nurse’s independent practice (e.g., patient education and symptom relief) compared with the dependent practice driven by physicians’ orders (e.g., medication administration and intravenous fluids). Initially professional nursing did not support nursing diagnoses. The Model Nurse Practice Act of the American Nurses Association (ANA) (1955) excluded diagnosis or prescriptive therapies. As a result, few nurses used nursing diagnoses in their practice.

When Yura and Walsh (1967) developed the theory of the nursing process, it included four parts: assessment, planning, implementation, and evaluation. However, nurse leaders soon recognized that assessment data needed to be clustered into patterns and interpreted before nurses could complete the remaining steps of the process (NANDA International, 2012). You cannot plan and then intervene correctly if you do not know the problems with which you are dealing. In 1973 the first national conference to identify the interpretations of data that represent the health conditions that are of a concern to nursing was held. The first conference on nursing diagnosis identified and defined 80 nursing diagnoses (Gebbie, 1998). The list continues to grow on the basis of nursing research and the work of members of the North American Nursing Diagnosis Association International (NANDA-I) (NANDA International, 2012).

With use of the term nursing diagnosis, nurses make diagnostic conclusions and therefore the clinical decisions necessary for safe and effective nursing practice. The ANA’s paper Scope of Nursing Practice (1987), which defined nursing as the diagnosis and treatment of human responses to health and illness, helped strengthen the definition of nursing diagnosis. In 1980 and 1995 the ANA included diagnosis as a separate activity in its publication Nursing: a Social Policy Statement (ANA, 2003). It continues today in the ANA’s most recent policy statement (ANA, 2010). As a result, most state Nurse Practice Acts include nursing diagnosis as part of the domain of nursing practice.

Research in the field of nursing diagnosis continues to grow (Box 17-1). As a result, NANDA-I continually develops and adds new diagnostic labels to the NANDA International listing (Box 17-2). The use of standard formal nursing diagnostic statements serves several purposes in nursing practice:

• Distinguishes the nurse’s role from that of the physician or other health care provider

• Helps nurses focus on the scope of nursing practice

• Fosters the development of nursing knowledge

• Promotes creation of practice guidelines that reflect the essence of nursing

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree