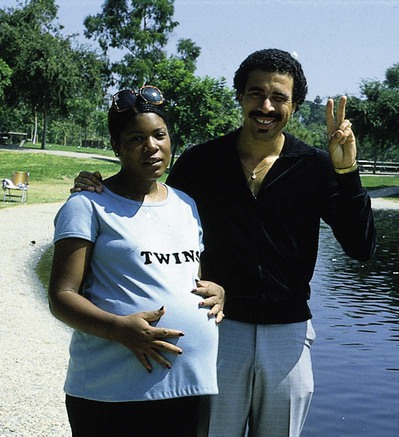

Chapter 8 On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Describe the processes of confirming pregnancy and estimating the date of birth. • Summarize the physical, psychosocial, and behavioral changes that usually occur as the mother and other family members adapt to pregnancy. • Evaluate the benefits of prenatal care and problems of accessibility for some women. • Outline the patterns of health care used to assess maternal and fetal health status at the initial visit and follow-up visits during pregnancy. • Conceptualize common nursing assessments, diagnoses, interventions, and methods of evaluation in providing care for the pregnant woman. • Plan education needed by pregnant women to understand physical discomforts related to pregnancy and to recognize the signs and symptoms of potential complications. • Examine the effect of culture, age, parity, and number of fetuses on the response of the family to the pregnancy and on the prenatal care provided. • Determine the scope of childbirth and perinatal education in the community. • Compare philosophies underlying maternal choices for childbirth. • Describe the available options for health care providers and birth setting choices. In recent years, the concept of preconception care has been recognized as an important contributor to good pregnancy outcomes (see Chapter 3). If women can be taught healthy lifestyle behaviors and then practice them before conception—specifically, good nutrition, entering pregnancy with as healthy a weight as possible, adequate intake of folic acid, avoidance of alcohol and tobacco use, prevention of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and other health hazards—a healthier pregnancy may result. Likewise, women who have health problems related to chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus can be counseled regarding their special needs with the intent to minimize maternal and fetal complications. Women often suspect pregnancy when they miss a menstrual period. Many women come to the first visit after a positive home pregnancy test; however, the clinical diagnosis of pregnancy before the second missed period can be difficult in some women. Physical variations, obesity, or tumors, for example, can confound even the experienced examiner. Accuracy is important because emotional, social, medical, or legal consequences related to an inaccurate diagnosis, either positive or negative, can be extremely serious. A correct date for the first day of the last (normal) menstrual period (LMP), the date of intercourse, and a basal body temperature record can be of great value in the accurate diagnosis of pregnancy (see Chapter 5). Great variability is possible in the subjective symptoms and objective signs of pregnancy. Therefore the diagnosis of pregnancy may be uncertain for a time. It is based on signs and symptoms that are reported during history taking or found during physical examination. These signs and symptoms are classified as presumptive, probable, and positive (see Table 8-2). When pregnancy is confirmed, the woman’s first question usually concerns when she will give birth. This date has traditionally been called the estimated date of confinement or estimated date of delivery. However, to promote a more positive perception of both pregnancy and birth, the term estimated date of birth (EDB) is now used. Accurate dating of pregnancy and calculation of the EDB have implications for timing of specific prenatal screening tests, assessing fetal growth, and making critical decisions for managing pregnancy complications. Ultrasound dating of gestational age is accurate, especially during the first half of pregnancy (ACOG, 2009). The first step in adapting to the maternal role is accepting the idea of pregnancy and assimilating the pregnant state into the woman’s way of life. Mercer (1995) described this process as cognitive restructuring and credited Rubin (1975, 1984) as the nurse theorist who pioneered our understanding of maternal role attainment. Intense feelings of ambivalence that persist through the third trimester can indicate an unresolved conflict with the motherhood role (Mercer, 1995). After the birth of a healthy child, memories of these ambivalent feelings usually are dismissed. If the child is born with a defect, a woman may look back at the times when she did not want the pregnancy and feel intense guilt. She may believe that her ambivalence caused the birth defect. She will then need reassurance that her feelings were not responsible for the problem. The woman’s relationship with her mother is significant in adapting to pregnancy and motherhood. Important components in the pregnant woman’s relationship with her mother are the mother’s availability (past and present), her reactions to the daughter’s pregnancy, respect for her daughter’s autonomy, and the willingness to reminisce (Mercer, 1995). The mother’s reaction to the daughter’s pregnancy signifies her acceptance of the grandchild and of her daughter. If the mother is supportive, the daughter has an opportunity to discuss pregnancy and labor and her feelings of joy or ambivalence with a knowledgeable and accepting woman (Fig. 8-1). Reminiscing about the pregnant woman’s early childhood and sharing the prospective grandmother’s account of her childbirth experience help the daughter anticipate and prepare for labor and birth. Although the woman’s relationship with her mother is significant in considering her adaptation in pregnancy, the most important person to the pregnant woman is usually the father of her child. Women express two major needs within this relationship during pregnancy: feeling loved and valued and having the child accepted by the partner (Fig. 8-2). The marital or committed relationship is not static but, instead, evolves over time. The addition of a child changes forever the nature of the bond between partners. This can be a time when couples grow closer and the pregnancy has a maturing effect on the partners’ relationship as they assume new roles and discover new aspects of one another. Partners who trust and support each other are able to share mutual dependency needs (Mercer, 1995). Emotional attachment—feelings of being tied by affection or love—begins during the prenatal period as women use fantasizing and daydreaming to prepare themselves for motherhood (Rubin, 1975). They think of themselves as mothers and imagine maternal qualities they would like to possess. Expectant parents desire to be warm, loving, and close to their child. They try to anticipate changes that the child will bring in their lives and wonder how they will react to noise, disorder, reduced freedom, and caregiving activities. The mother-child relationship progresses through pregnancy as a developmental process that unfolds in three phases. Anxiety can arise from concern about safe passage for herself and her child during the birth process (Mercer, 1995; Rubin, 1975). This concern may not be expressed overtly, but cues are given as the nurse listens to plans women make for care of the new baby and other children in case “anything should happen.” These feelings persist despite statistical evidence about the safe outcome of pregnancy for mothers and their infants. Many women fear the pain of childbirth or mutilation because they do not understand anatomy and the birth process. Education by the nurse can alleviate many of these fears. The man’s emotional response to becoming a father, his concerns, and his informational needs change during the course of pregnancy. Phases of the developmental pattern become apparent. May (1982) described three phases characterizing the developmental tasks experienced by the expectant father: • The announcement phase may last from a few hours to a few weeks. The developmental task is to accept the biologic fact of pregnancy. Men react to the confirmation of pregnancy with joy or dismay, depending on whether the pregnancy is desired, unplanned, or unwanted. Ambivalence in the early stages of pregnancy is common. If pregnancy is unplanned or unwanted, some men find the alterations in life plans and lifestyles difficult to accept. Some men engage in extramarital affairs for the first time during their partner’s pregnancy. Others batter their wives for the first time or escalate the frequency of battering episodes. • The second phase, the moratorium phase, is the period when he adjusts to the reality of pregnancy. The developmental task is to accept the pregnancy. Men appear to put conscious thought of the pregnancy aside for a time. They become more introspective and engage in many discussions about their philosophy of life, religion, childbearing, and childrearing practices and their relationships with family members, particularly with their father. Depending on the man’s readiness for the pregnancy, this phase may be relatively short or persist until the last trimester. • The third phase, the focusing phase, begins in the last trimester and is characterized by the father’s active involvement in both the pregnancy and his relationship with his child. The developmental task is to negotiate with his partner the role he is to play in labor and to prepare for parenthood. In this phase, the man concentrates on his experience of the pregnancy and begins to think of himself as a father. • What do you expect the baby to look and act like? • What do you think being a father will be like? • Have you thought about the baby’s crying? Changing diapers? Burping the baby? Being awakened at night? Sharing your partner with the baby? Some fathers may not wish to answer such questions when they are asked but may need time to think them through or discuss them with their partners. A mother with other children must devote time and energy to reorganizing her relationships with these children. She needs to prepare siblings for the birth of the baby (Fig. 8-3 and Box 8-1). She can begin the process of role transition in the family by including the children in the pregnancy and being sympathetic to older children’s concerns about losing their places in the family hierarchy. No child willingly gives up a familiar position. By age 3 or 4 years, children like to be told the story of their own beginning and accept its being compared to the present pregnancy. They like to listen to heartbeats and feel the baby moving in utero (see Fig. 8-3). Sometimes they worry about how the baby is being fed and what it wears. The grandparent is the historian who transmits the family history, a resource person who shares knowledge based on experience, a role model, and a support person. The grandparent’s presence and support can strengthen family systems by widening the circle of support and nurturance (Fig. 8-5). Other sources of information cannot replace the unique contribution that grandparents make (www.grandparents.com; www.grandparenting.org). The goal of prenatal care is to promote the health and well-being of the pregnant woman, her fetus, the newborn, and the family (Gregory, Niebyl, and Johnson, 2012). Major emphasis is placed on preventive aspects of care, primarily to motivate the pregnant woman to practice optimal self-management and report unusual changes early so that problems can be minimized or prevented. In holistic care, nurses provide information and guidance about not only the physical changes but also the psychosocial impact of pregnancy on the woman and members of her family. Therefore the goals of prenatal nursing care are to promote positive pregnancy outcomes, to foster a safe birth for the infant and mother, and to promote satisfaction of the mother and family with the pregnancy and birth experience. According to the National Center for Health Statistics, based on data from 27 states and Puerto Rice, 71% of women received prenatal care in the first trimester. Only 7% of women started prenatal care late (during third trimester) or had no prenatal care. The subgroups most likely to receive late or no prenatal care were American Indian, Alaska Native, African-American, and Hispanic (Osterman, Martin, Mathews, et al., 2011). Although women of middle or high socioeconomic status routinely seek prenatal care, women living in poverty or those who lack health insurance are not always able to use public health care services or gain access to private care. Lack of culturally sensitive care providers and barriers in communication caused by differences in language also interfere with access to care. Immigrant women from cultures in which prenatal care is not emphasized may not know to seek routine prenatal care. Thus birth outcomes in these populations are less positive, with higher rates of maternal and fetal or newborn complications. In particular, problems with low birth weight (LBW) (less than 2500 g [5.5 lb]) and infant mortality have been associated with inadequate prenatal care (Cunningham, Leveno, Bloom, et al., 2010). Barriers to obtaining health care during pregnancy include a lack of motivation to seek care, especially for unintended pregnancies; inadequate finances; lack of transportation; unpleasant clinic personnel, facilities, or procedures; inconvenient clinic hours; child care problems; and personal attitudes (Novick, 2009; Phillippi, 2009). The availability and accessibility of prenatal care may be improved by increasing the use of advanced practice nurses in collaborative practice with physicians or midwives. A regular schedule of home visits by nurses aids in reducing barriers to care and contributes to improved maternal and infant outcomes (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ] Healthcare Innovations Exchange, 2012). The traditional model for provision of prenatal care has been used for more than a century. The initial visit usually occurs in the first trimester, with monthly visits through week 28 of pregnancy. Thereafter, visits are scheduled every 2 weeks until week 36 and then every week until birth. More recently, the trend is toward individualizing the schedule of care. Women with low-risk pregnancies may have fewer routine prenatal visits, whereas those at risk for complications may be seen more frequently than the traditional schedule (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP] Committee on Fetus and Newborn and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG] Committee on Obstetric Practice, 2012). Group prenatal care is an alternative model to traditional care during pregnancy. In group prenatal care, authority is shifted from the provider to the woman and other women who have similar due dates. The model creates an atmosphere that facilitates learning, encourages discussion, and develops mutual support. CenteringPregnancy (https://www.centeringhealthcare.org/) is a well-known model of group prenatal care that involves three components: health care assessment, education, and peer support. Most care takes place in the group setting after the initial visit and continues for ten 2-hour sessions that begin at about 16 weeks. At each meeting, the first 30 to 40 minutes consists of assessments (by the woman herself and by the health care provider) and the remaining 60 to 75 minutes is spent in group discussion of specific issues such as discomforts of pregnancy and preparation for labor and birth. Families and partners are encouraged to participate. Benefits associated with group prenatal care include improved birth outcomes such as lower rates of preterm birth, increased knowledge, improved satisfaction, and higher breastfeeding initiation rates (Herrman, Rogers, and Ehrenthal, 2012; Picklesimer, Billings, Hale, et al., 2012; Rotundo, 2011; Robertson, Aycock, and Darnell, 2009). In recent years, the concept of preconception care has been recognized as an important contributor to good pregnancy outcomes (see Chapter 3). If women can be taught healthy lifestyle behaviors and then practice them before conception—specifically, good nutrition, entering pregnancy with as healthy a weight as possible, adequate intake of folic acid, avoidance of alcohol and tobacco use, prevention of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and other health hazards—a healthier pregnancy may result. Likewise, women who have health problems related to chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus can be counseled regarding their special needs with the intent to minimize maternal and fetal complications. With the woman’s permission, include persons accompanying her in the initial prenatal interview (Fig. 8-6). Observations and information about the woman’s partner and/or family are then included in the database. For example, if the woman has small children with her, the nurse can ask about her plans for child care during the time of labor and birth. Note any special needs at this time (e.g., wheelchair access, assistance in getting on and off the examining table, and cognitive deficits). Women may forget to mention chronic or handicapping conditions during the initial assessment because they have adapted to them. Special shoes or a limp may indicate the existence of a pelvic structural defect—an important consideration in pregnant women. The nurse who observes these special characteristics and sensitively inquires about them can obtain individualized data that will provide the basis for a comprehensive nursing care plan to help optimize pregnancy outcomes (Signore, Spong, Krotoski, et al., 2011). Observations are a vital component of the interview process because they prompt the nurse and the woman to focus on the specific needs of the woman and her family. The nutritional status of a pregnant woman has a direct effect on the growth and development of the fetus. A dietary assessment can reveal special diet practices, food allergies, eating behaviors, the practice of pica, and other factors related to her nutritional status (see Box 9-7). Pregnant women are usually motivated to learn about good nutrition and respond well to nutritional advice generated by this assessment. It is essential that obese women receive counseling about weight gain, nutrition, and food choices. They should also be advised about their risk for complications for themselves and increased risk for congenital abnormalities (Davies, Maxwell, McLeod, et al., 2010). Women with a history of bariatric surgery are nutritionally at risk and should be followed closely throughout pregnancy to promote maternal and fetal well-being (Magdaleno, Pereira, Chaim, et al., 2012). A woman’s past and present use of drugs, both legal (over-the-counter [OTC], prescription, and herbal drugs; caffeine; alcohol; nicotine) and illegal (marijuana, cocaine, heroin), must be assessed because many substances cross the placenta and can harm the developing fetus. See Chapter 11 for discussion of substance abuse during pregnancy. Increasing numbers of individuals are using herbal preparations, and this includes pregnant women. Therefore it is important for health care providers to question pregnant women regarding the use of herbal preparations and document their responses. • Is this pregnancy planned or unintended? • Is the woman/couple pleased or displeased, accepting or nonaccepting? • What problems related to finances, career, or living accommodations may arise as a result of the pregnancy? The family support system is determined by asking her such questions as: • Which roles does she expect her significant other or father of the baby to play? • Are changes needed to promote adequate support? • What are the existing relationships among mother, father/partner, siblings, and in-laws? • What preparations are being made for her care and that of dependent family members during labor and for the care of the infant after birth? • Is financial, educational, or other support needed from the community? • What are the woman’s ideas about childbearing, her expectations of the infant’s behavior, and her outlook on life and the female role? Other questions that should be asked include: • What does the woman think it will be like to have a baby in the home? • How is her life going to change by having a baby? During interviews throughout the pregnancy, the nurse should remain alert for the appearance of potential parenting problems such as depression, lack of family support, and inadequate living conditions. The nurse must assess the woman’s attitude toward health care, particularly during childbearing; her expectations of health care providers; and her view of the relationship between herself and the nurse. All women should be assessed for a history of or risk for physical abuse, particularly because the likelihood of intimate partner violence (IPV) increases during pregnancy (see Chapter 3). This screening should be done at the first prenatal visit, at least once each trimester, and at the postpartum visit (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women, 2012a). It is essential that the screening is done in a safe, private setting with the woman alone. Nurses can ask the woman screening questions with routine assessments during pregnancy. Examples of questions that might be asked include: • Are you with a spouse or partner who threatens or physically hurts you? If yes, who? • Within the past year or in this pregnancy, has anyone hit, slapped, kicked, or otherwise hurt you? If yes, who? Are you currently with that person? • Has anyone forced you to have sexual activities that made you uncomfortable? If yes, who? Are you currently with that person? Although visual cues from the woman’s appearance or behavior may suggest the possibility of abuse, no one profile of the battered woman exists. Identification of abuse and immediate clinical intervention that includes information about safety can result in behavior that may prevent future abuse and increase the safety and well-being of the woman and her infant. During pregnancy, the target body parts change during abusive episodes. Women report physical blows directed to the head, breasts, abdomen, and genitalia. Sexual assault is common. Nurses should be aware that victims of human trafficking may be seen in prenatal settings because of unintended pregnancy. These women or young girls are forced or deceived into commercial sex acts (prostitution) with little or no pay. They are under strict control by their traffickers. Similar to victims of IPV, these women are likely to exhibit signs of physical abuse or neglect such as scars, bruises, burns, unusual bald patches, or tattoos that may be a sign of branding. They are likely to be accompanied by someone who never leaves them alone and speaks for them. They may not speak English and may lack identification documents. If the woman is alone, she may have her cell phone on and in speaker mode so that the person on the other end can hear everything that is said during the visit. Nurses and other health care providers must be creative in getting the woman alone for questioning. Strategies might include sending the other person to the front desk to fill out paperwork, interviewing the woman in the restroom, or telling her she needs to go for testing and cannot take her cell phone. With the consent of suspected or confirmed victims of human trafficking, intervention plans can be developed. An excellent resource is the National Human Trafficking Resource Center (1-888-373-7888) (Dovydaitis, 2010; Tracy and Konstantopoulos, 2012). During the review of systems, ask the woman to identify and describe pre-existing or concurrent problems in any of the body systems and assess her mental status. Question the woman about physical symptoms she has experienced such as shortness of breath or pain. Pregnancy affects and is affected by all body systems; therefore information on the present status of body systems is important in planning care. For each sign or symptom described, the following additional data should be obtained: body location, quality, quantity, chronology, aggravating or alleviating factors, and associated manifestations (onset, character, and course) (Seidel, Ball, Dains, et al., 2011). The physical examination begins with assessment of vital signs, including blood pressure (BP), height, and weight (for calculation of body mass index [BMI]) (see Chapter 9). The bladder should be empty before pelvic examination. Each examiner develops a routine for proceeding with the physical examination; most choose the head-to-toe progression. Heart and lung sounds are evaluated, and extremities are examined. The skin is assessed for changes in pigmentation, rashes, and edema. Distribution, amount, and quality of body hair are of particular importance because the findings reflect nutritional status, endocrine function, and attention to hygiene. The thyroid gland is assessed carefully, as are the breasts and abdomen. The height of the fundus is noted if the first examination occurs after the first trimester of pregnancy. During the examination, the examiner must remain alert to the woman’s cues that give direction to the remainder of the assessment and that indicate imminent untoward response, such as feeling lightheaded or dizzy. See Chapter 3 for a detailed description of the physical examination. Specimens are collected at the initial visit so that any abnormal findings can be treated. Blood is drawn for a variety of tests (Table 8-1). A sickle cell screen is recommended for women of African, Asian, or Middle Eastern heritage. Testing for antibody to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is strongly recommended for all pregnant women; this testing must be voluntary and without coercion (ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice, 2011a; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2010) (Box 8-2). The folate level is measured when indicated. Cystic fibrosis (CF) carrier screening tests should be offered to all pregnant women; if the woman is a CF carrier, the father of the baby should be tested. Concurrent testing is recommended if there are time constraints related to prenatal diagnostic evaluation (ACOG Committee on Genetics, 2011). A urine specimen is collected for cultures and metabolic function tests. A purified protein derivative tuberculin test may be administered to assess exposure to tuberculosis. During the pelvic examination, cervical and vaginal smears can be obtained for cytologic studies and for diagnosis of infection (e.g., chlamydia, gonorrhea). TABLE 8-1 LABORATORY TESTS IN THE PRENATAL PERIOD Recognition of risk factors during pregnancy may indicate the need to repeat some tests at other times. For example, exposure to tuberculosis or an STI would necessitate repeat testing. STIs are common in pregnancy and may have negative effects on mother and fetus (see Table 4-5 on p. 98). Careful assessment and thorough screening are essential.

Nursing Care of the Family During Pregnancy

Diagnosis of Pregnancy

Signs and Symptoms

Estimating Date of Birth

Adaptation to Pregnancy

Maternal Adaptation

Accepting the Pregnancy

Reordering Personal Relationships

Establishing a Relationship with the Fetus

Preparing for Childbirth

Paternal Adaptation

Accepting the Pregnancy

Establishing a Relationship with the Fetus

Sibling Adaptation

Grandparent Adaptation

Care Management

Initial Visit

Interview

Health History

Nutritional History

History of Use of Drugs and Herbal Preparations

Social, Experiential, and Occupational History

History of Physical Abuse

Review of Systems

Physical Examination

Laboratory Tests

LABORATORY TEST

PURPOSE

Hemoglobin, hematocrit/WBC, differential

Detects anemia/detects infection

Hemoglobin electrophoresis

Identifies women with hemoglobinopathies (e.g., sickle cell anemia, thalassemia)

Blood type, Rh, and irregular antibody

Identifies fetuses at risk for developing erythroblastosis fetalis or hyperbilirubinemia in neonatal period

Rubella titer

Determines immunity to rubella

Tuberculin skin testing; chest film after 20 wk of gestation in women with reactive tuberculin tests

Screens for exposure to tuberculosis

Urinalysis, including microscopic examination of urinary sediment; pH, specific gravity, color, glucose, albumin, protein, RBCs, WBCs, casts, acetone; hCG

Identifies women with glycosuria, renal disease, hypertensive disease of pregnancy; infection; occult hematuria

Urine culture

Identifies women with asymptomatic bacteriuria

Renal function tests: BUN, creatinine, electrolytes, creatinine clearance, total protein excretion

Evaluates level of possible renal compromise in women with a history of diabetes, hypertension, or renal disease

Papanicolaou test

Screens for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; if a liquid-based test is used, may also screen for HPV

Vaginal or rectal smear for Neisseria gonorrhoeae, chlamydia, HPV, GBS

Screens high risk population for asymptomatic infection; GBS done at 35-37 wk

RPR/VDRL/FTA-ABS

Identifies women with untreated syphilis

HIV antibody,* hepatitis B surface antigen, toxoplasmosis

Screens for the specific infection

1-hr glucose tolerance

Screens for gestational diabetes; done at initial visit for women with risk factors; done at 24-28 wk for pregnant women at risk whose initial screen was negative; women with low risk usually not tested

3-hr glucose tolerance

Screens for diabetes in women with elevated glucose level after 1-hr test; must have two elevated readings for diagnosis

Cardiac evaluation: ECG, chest x-ray film, and echocardiogram

Evaluates cardiac function in women with a history of hypertension or cardiac disease

Nursing Care of the Family During Pregnancy

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access