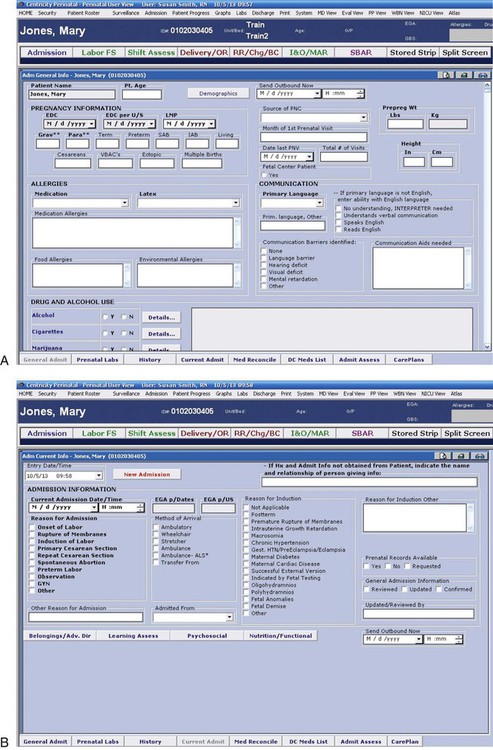

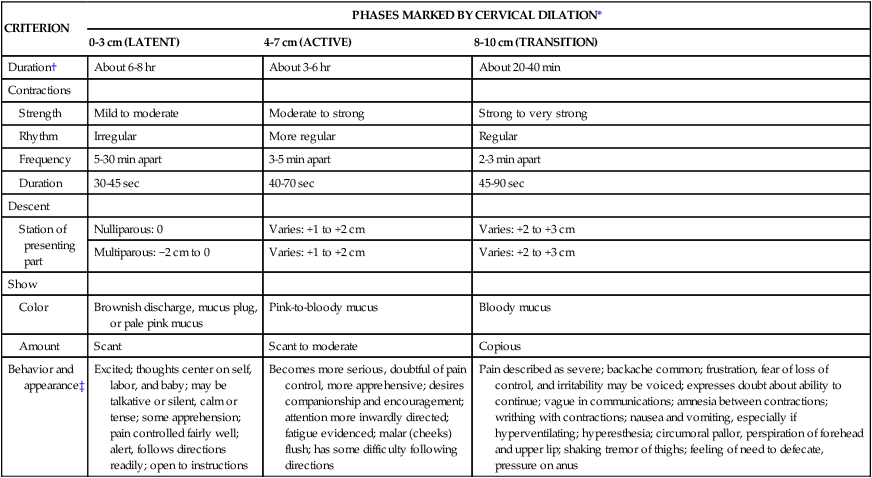

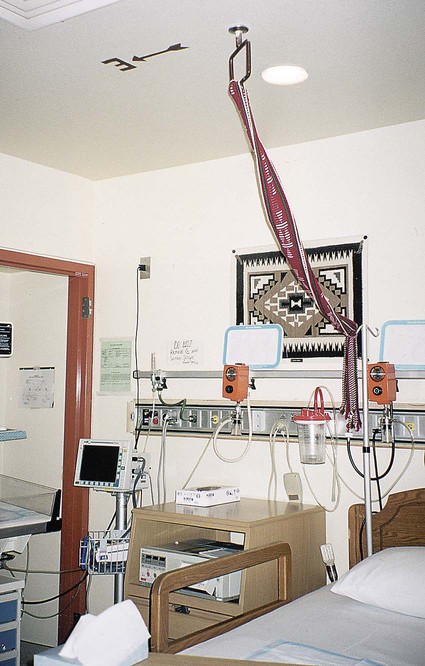

Chapter 16 On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Review the factors included in the initial assessment of the woman in labor. • Describe the ongoing assessment of maternal progress during the first, second, third, and fourth stages of labor. • Recognize the physical and psychosocial findings indicative of maternal progress during labor. • Describe fetal assessment during labor. • Identify signs of developing complications during labor and birth. • Incorporate evidence-based nursing interventions into a comprehensive plan of care relevant to each stage of labor. • Recognize the importance of support (family, partner, doula, nurse) in fostering maternal confidence and facilitating the progress of labor and birth. • Analyze the influence of cultural and religious beliefs and practices on the process of labor and birth. • Evaluate research findings on the importance of support from family, partner, doula, and nurse in facilitating maternal progress during labor and birth. • Describe the role and responsibilities of the nurse during emergency childbirth. • Evaluate the impact of perineal trauma on the woman’s reproductive and sexual health. Assessment begins at the first contact with the woman, whether by telephone or in person. Many women call the hospital or birthing center first for validation that it is all right for them to come in for evaluation or admission or that they can remain at home. However, many hospitals discourage the nurse from giving advice regarding what to do because of legal liability. Nurses are often instructed to tell women who call with questions to call their primary health care provider or to come to the hospital if they feel the need to be checked. The nature of the telephone conversation, including any advice or instructions given, should be documented in the patient’s record (Gilbert, 2011). A warm shower is often relaxing during early labor. However, warm baths before labor is well established could inhibit uterine contractions and prolong the labor process (Waterbirth International, 2012). Soothing back, foot, and hand massage or a warm drink of preferred liquids such as tea or milk can help the woman rest and even sleep, especially if false or early labor is occurring at night. Diversional activities such as walking outdoors or in the house, reading, watching television, “playing” on the computer, or talking with friends can reduce the perception of early discomfort, help time pass, and reduce anxiety. When the woman arrives at the perinatal unit, assessment is the top priority (Fig. 16-1). The nurse first performs a screening assessment by using the techniques of interview and physical assessment and reviews the laboratory and diagnostic test findings to determine the health status of the woman and her fetus and the progress of her labor. The nurse also notifies the primary health care provider; and, if the woman is admitted, a detailed systems assessment is done. Most hospitals have specific forms, whether paper or electronic, that are used to obtain important assessment information when a woman in labor is being evaluated or admitted (Fig. 16-2, A and B). More and more hospitals now use an electronic medical record; almost all charting is done on computer. Sources of data include the prenatal record, initial interview, physical examination to determine baseline physiologic parameters (e.g., vital signs), laboratory and diagnostic test results, expressed psychosocial and cultural factors, and clinical evaluation of labor status. The nurse should review the woman’s prenatal records carefully, taking note of her obstetric and pregnancy history, including gravidity; parity; and problems such as history of vaginal bleeding, gestational hypertension, anemia, pregestational or gestational diabetes, infections (e.g., bacterial, viral, sexually transmitted), and immunodeficiency status. In addition, the expected date of birth (EDB) should be confirmed. Other important data found in the prenatal record include patterns of maternal weight gain; physiologic measurements such as maternal vital signs (blood pressure, temperature, pulse, respirations); fundal height; baseline fetal heart rate (FHR); and laboratory and diagnostic test results. See Table 8-1 for a list of common prenatal laboratory tests. Common diagnostic and fetal assessment tests performed prenatally include amniocentesis, nonstress test (NST), biophysical profile (BPP), and ultrasound examination. See Chapter 10 for more information. • Time and onset of contractions and progress in terms of frequency, duration, and intensity • Location and character of discomfort from contractions (e.g., back pain, abdominal or suprapubic discomfort) • Persistence of contractions despite changes in maternal position and activity (e.g., walking or lying down) • Presence and character of vaginal discharge or “show” • The status of amniotic membranes such as a gush or seepage of fluid (spontaneous rupture of membranes [SROM]). If there has been a discharge that may be amniotic fluid, she is asked the date and time the fluid was first noted and its characteristics (e.g., amount, color, unusual odor). In many instances a sterile speculum examination and a Nitrazine (pH) and fern test can confirm that the membranes are ruptured (Box 16-1). These descriptions help the nurse assess the degree of progress in the process of labor. Bloody show is distinguished from bleeding by the fact that it is pink and feels sticky because of its mucoid nature. There is very little bloody show in the beginning, but the amount increases with effacement and dilation of the cervix. A woman may report a small amount of brownish-to-bloody discharge that may be attributed to cervical trauma resulting from vaginal examination or coitus (intercourse) within the last 48 hours. The nurse obtains any information not found in the prenatal record during the admission assessment. Pertinent data include the birth plan (Box 16-2), the choice of infant feeding method, the type of pain management preferred, and the name of the pediatric health care provider. Obtain a patient profile that identifies the woman’s preparation for childbirth, the support person or family members desired during childbirth and their availability, and ethnic or cultural expectations and needs. Determine the woman’s use of alcohol, drugs, and tobacco before or during pregnancy. The woman’s general appearance and behavior (and that of her partner) provide valuable clues to the type of supportive care she will need. However, keep in mind that general appearance and behavior may vary, depending on the stage and phase of labor (Table 16-1 and Box 16-3). TABLE 16-1 EXPECTED MATERNAL PROGRESS DURING FIRST STAGE OF LABOR *In the nullipara effacement is often complete before dilation begins; in the multipara it occurs simultaneously with dilation. †Duration of each phase is influenced by such factors as parity; maternal emotions; position; level of activity; and fetal size, presentation, and position. For example, the labor of a nullipara tends to last longer, on average, than the labor of a multipara. Women who ambulate and assume upright positions or change positions frequently during labor tend to experience a shorter first stage. Descent is often prolonged in breech presentations and occiput posterior positions. ‡Women who have epidural analgesia for pain relief may not demonstrate some of these behaviors. The nurse can help the abuse survivor associate the sensations she is experiencing with the process of childbirth and not with her past abuse. Help maintain her sense of control by explaining all procedures and why they are needed, validating her needs, and paying close attention to her requests. Wait for the woman to give permission before touching her, and accept her often extreme reactions to labor (Simpson, 2008). Avoid words and phrases that can cause the woman to recall the words of her abuser (e.g., “open your legs,” “relax and it won’t hurt so much”). Limit the number of procedures that invade her body (e.g., vaginal examinations, urinary catheter, internal monitor, forceps or vacuum extractor) as much as possible. Encourage her to choose a person (e.g., doula, friend, family member) to be with her during labor to provide continuous support and comfort and act as her advocate. Nurses are advised to care for all laboring women in this manner because it is not unusual for a woman to choose not to reveal a history of sexual abuse. These care measures can help a woman perceive her childbirth experience in positive terms. As the population in the United States and Canada becomes more diverse, it is increasingly important to note the woman’s ethnic or cultural and religious values, beliefs, and practices to anticipate nursing interventions to add or eliminate from an individualized, mutually acceptable plan of care that provides a feeling of safety and control (Fig. 16-3). Nurses should be committed to providing culturally sensitive care and developing an appreciation and respect for cultural diversity (Callister, 2008). Encourage the woman to request specific caregiving behaviors and practices that are important to her. If a special request contradicts usual practices in that setting, the woman or the nurse can ask the woman’s primary health care provider to write an order to accommodate the special request. For example, in many cultures it is unacceptable to have a male caregiver examine a pregnant woman. In some cultures it is traditional to take the placenta home; in others the woman has only certain nourishments during labor. Some women believe that cutting her body, as with an episiotomy, allows her spirit to leave her body and that rupturing the membranes prolongs, not shortens, labor. It is important to explain the rationale for required care measures carefully (see Cultural Competence box). Within cultures women may have an idea of the “right” way to behave in labor and may react to the pain experienced in that way. These behaviors can range from total silence to moaning or screaming, but they do not necessarily indicate the degree of pain. A woman who moans with contractions may not be in as much physical pain as a woman who is silent but winces during contractions. Some women believe that screaming or crying out in pain is shameful if a man is present. If the woman’s support person is her mother, she may perceive the need to “behave” more strongly than if her support person is the father of the baby. She perceives herself as failing or succeeding based on her ability to follow these “standards” of behavior. Conversely a woman’s behavior in response to pain may influence the support received from significant others. In some cultures women who lose control and cry out in pain may be scolded, whereas in others support persons become more helpful (D’Avanzo, 2008). The initial physical examination includes a general systems assessment and an assessment of fetal status. During the examination uterine contractions are assessed, and a vaginal examination is performed. The findings of the admission physical examination serve as a baseline for assessing the woman’s progress from that point. The information obtained from a complete and accurate assessment during the initial examination serves as the basis for determining whether the woman should be admitted and what her ongoing care should be. Expected maternal progress and minimal assessment guidelines during the first stage of labor are presented in Table 16-1 and Box 16-4.

Nursing Care of the Family During Labor and Birth

Care Management

Assessment

Prenatal Data

Interview

Psychosocial Factors

CRITERION

PHASES MARKED BY CERVICAL DILATION*

0-3 cm (LATENT)

4-7 cm (ACTIVE)

8-10 cm (TRANSITION)

Duration†

About 6-8 hr

About 3-6 hr

About 20-40 min

Contractions

Strength

Mild to moderate

Moderate to strong

Strong to very strong

Rhythm

Irregular

More regular

Regular

Frequency

5-30 min apart

3-5 min apart

2-3 min apart

Duration

30-45 sec

40-70 sec

45-90 sec

Descent

Station of presenting part

Nulliparous: 0

Varies: +1 to +2 cm

Varies: +2 to +3 cm

Multiparous: −2 cm to 0

Varies: +1 to +2 cm

Varies: +2 to +3 cm

Show

Color

Brownish discharge, mucus plug, or pale pink mucus

Pink-to-bloody mucus

Bloody mucus

Amount

Scant

Scant to moderate

Copious

Behavior and appearance‡

Excited; thoughts center on self, labor, and baby; may be talkative or silent, calm or tense; some apprehension; pain controlled fairly well; alert, follows directions readily; open to instructions

Becomes more serious, doubtful of pain control, more apprehensive; desires companionship and encouragement; attention more inwardly directed; fatigue evidenced; malar (cheeks) flush; has some difficulty following directions

Pain described as severe; backache common; frustration, fear of loss of control, and irritability may be voiced; expresses doubt about ability to continue; vague in communications; amnesia between contractions; writhing with contractions; nausea and vomiting, especially if hyperventilating; hyperesthesia; circumoral pallor, perspiration of forehead and upper lip; shaking tremor of thighs; feeling of need to defecate, pressure on anus

Women with a History of Sexual Abuse.

Cultural Factors

Physical Examination

Nursing Care of the Family During Labor and Birth

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access