On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Describe current recommendations for infant feeding. • Explain the nurse’s role in helping families choose an infant feeding method. • Discuss benefits of breastfeeding for infants, mothers, families, and society. • Describe nutritional needs of infants. • Describe anatomic and physiologic aspects of breastfeeding. • Recognize newborn feeding-readiness cues. • Explain maternal and infant indicators of effective breastfeeding. • Examine nursing interventions to facilitate and promote successful breastfeeding. • Analyze common problems associated with breastfeeding and interventions to help resolve them. • Compare powdered, concentrated, and ready-to-use forms of commercial infant formula. Through preconception and prenatal education and counseling nurses play an instrumental role in helping parents make an informed decision about infant feeding. Scientific evidence is clear that human milk provides the best nutrition for infants, and parents should be strongly encouraged to choose breastfeeding (AAP Section on Breastfeeding, 2012). Although many consider commercial infant formula to be equivalent to breast milk, this belief is erroneous. Human milk is the gold standard for infant nutrition. It is species specific, uniquely designed to meet the needs of human infants. The composition of human milk changes to meet the nutritional needs of growing infants. It is highly complex, with antiinfective and nutritional components combined with growth factors, enzymes that aid in digestion and absorption of nutrients, and fatty acids that promote brain growth and development. Infant formulas are usually adequate in providing nutrition to maintain infant growth and development within normal limits, but they are not equivalent to human milk. Breastfeeding is defined as the transfer of human milk from the mother to the infant; the infant receives milk directly from the mother’s breast. Exclusive breastfeeding means that the infant receives no other liquid or solid food (AAP Section on Breastfeeding, 2012). If the infant is fed expressed breast milk from the mother or a donor milk bank, it is called human milk feeding. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life and that breastfeeding be continued as complementary foods are introduced. Breastfeeding should continue for 1 year and thereafter as desired by the mother and her infant (AAP Section on Breastfeeding, 2012). According to the Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding, endorsed by the World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), infants should be exclusively breastfed for 6 months, and breastfeeding should continue for up to 2 years and beyond (WHO and UNICEF, 2003). Exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life is also recommended by other professional health care organizations such as the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP, 2012), Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine (ABM Board of Directors, 2008), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women and Committee on Obstetric Practice, 2007), and the American Dietetic Association (ADA, 2009). The Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses (AWHONN, 2007) actively supports breastfeeding as the ideal form of infant nutrition and provides guidelines for nurses in promoting breastfeeding and supporting breastfeeding families. Breastfeeding rates in the United States have risen steadily over the past decade. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2012) reported that the U.S. breastfeeding initiation rate in 2009 was 76.9%, which is the highest ever reported. The 6-month breastfeeding rate was 47.2%, and the 12-month rate was 25.5%. The rate of exclusive breastfeeding at 3 months was 36% and at 6 months, 16.3%. In spite of the increases in breastfeeding rates, the United States continues to fall short of the Healthy People 2020 goals of 81% of infants ever breastfed, 60.6% breastfeeding at 6 months, and 34.1% at 12 months; goals for exclusive breastfeeding are 46.2% through 3 months and 25.5% through 6 months (USDHHS, 2010). Trends remain unchanged in breastfeeding rates among minority groups in the United States. The lowest breastfeeding rates are among non-Hispanic black women (Jensen, 2012), although the overall percentage of non-Hispanic black women who breastfeed has increased in recent years. The minority group most likely to breastfeed is Hispanic women (Scanlon, Grummer-Strawn, Li et al., 2010). Extensive evidence exists concerning the health benefits of breastfeeding and human milk for infants, with some of the benefits extending into adulthood (Table 24-1). These benefits are optimized when infants are breastfed exclusively and when the duration of breastfeeding is increased (Mass, 2011). The evidence supporting breastfeeding as the ideal form of infant nutrition is so strong that health care professionals may need to present information about it from two perspectives: benefits of and risks of not breastfeeding (Spatz and Lessen, 2011). TABLE 24-1 SIDS, Sudden infant death syndrome. Data from American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding: Breastfeeding and the use of human milk—policy statement, Pediatrics 129(3):e827-e841, 2012; Stuebe A: The risks of not breastfeeding for mothers and infants, Rev Obstet Gynecol 2(4):222-231, 2009; Ip S, Chung M, Raman G, et al: A summary of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s evidence report on breastfeeding in developed countries, Breastfeed Med 4(suppl 1):S17-S30, 2009. Breastfeeding is associated with health benefits for mothers (see Table 24-1). The benefits are increased with the number of children who were breastfed and the total length of time of lactation. The economic benefits of breastfeeding affect families, employers, insurers, and the entire nation. Because infant formula is expensive, breastfeeding represents a significant savings for families. It reduces health care costs and decreases employee absenteeism. It has been estimated that the United States could save $13 billion dollars per year and more than 900 infant deaths could be prevented if 90% of infants were breastfed exclusively for 6 months (Bartick and Reinhold, 2010). Breastfeeding has environmental benefits. It reduces the waste that is deposited in landfills, including formula packaging, bottles, nipples, and other equipment. There is no need for fuel to prepare or transport human milk, which saves energy resources (USDHHS, 2011). For most women there is a clear choice to either breastfeed or formula feed. In some cases women decide to combine breastfeeding and formula feeding. However, this practice may be associated with a shorter duration of breastfeeding (Holmes, Auinger, and Howard, 2011). In some instances women want their infants to receive breast milk but prefer not to feed directly from their breasts. Women most often choose to breastfeed because they are aware of the benefits to the infant (Nelson, 2012). This reinforces the importance of prenatal education about the numerous benefits of breastfeeding. Cultural factors influence infant feeding decisions. For example, in the Hispanic culture breastfeeding is the norm, whereas formula feeding is more common among African-American families (see Cultural Competence box). The decision to breastfeed exclusively is related to the mother’s knowledge about the health benefits to the infant and her comfort level with breastfeeding in social settings (Stuebe and Bonuck, 2011). The likelihood that women will breastfeed exclusively may be greater if they made the decision to do so during pregnancy (Tenfelde, Finnegan, and Hill, 2011). There appears to be a relationship between maternal weight and infant feeding decisions. Women who are overweight or obese are less likely to breastfeed than women who are underweight or of average weight (Mehta, Siega-Riz, Herring, et al., 2011). Other factors influence decisions about infant nutrition. Social and systemic factors create obstacles or barriers to breastfeeding among women in the United States. These include a lack of broad social support for breastfeeding and the widespread marketing by infant formula companies. In addition, there is a lack of prenatal breastfeeding education for expectant parents and insufficient training/education of health care professionals about breastfeeding. In some institutions the policies and practices do not support exclusive breastfeeding (Mass, 2011). There is a lack of support for breastfeeding mothers during the first 2 to 3 weeks after birth when they are most likely to encounter difficulties. On a more personal level, a major obstacle for women is employment and the need to return to work after birth (Mass, 2011). A lack of support from the partner and family also creates obstacles to breastfeeding for many women. In a meta-synthesis of 14 qualitative studies about infant feeding decision making, Nelson (2012) reported common barriers to breastfeeding such as lack of comfort or uneasiness with breastfeeding, pain, lifestyle incompatibility, discomfort with public breastfeeding, and a lack of formal support. Parents who choose to formula feed often make this decision without complete information and understanding of the benefits of breastfeeding. Even women who are educated about the advantages of breastfeeding may still decide to formula feed. Cultural beliefs and myths and misconceptions about breastfeeding influence women’s decision making. Many women see bottle-feeding as more convenient or less embarrassing than breastfeeding. Some view formula feeding as a way to ensure that the father, other family members, and day care providers can feed the baby. Some women lack confidence in their ability to produce breast milk of adequate quantity or quality. Women who have had previous unsuccessful breastfeeding experiences may choose to formula feed subsequent infants. Some women see breastfeeding as incompatible with an active social life, or they think that it will prevent them from going back to work. Modesty issues and societal barriers exist against breastfeeding in public. A major barrier for many women is the influence of family and friends (Nelson, 2012). Women who participate in the Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) are more likely to formula feed (Jensen, 2012; Mass, 2011). Although in recent years WIC has improved food packages for breastfeeding families, many women on WIC decide to formula feed based on the perceived monetary value of infant formula as well as convenience and social factors (Jensen, 2012). Breastfeeding is contraindicated in a few circumstances. Newborns who have galactosemia should not receive human milk. Breastfeeding is contraindicated for mothers who are positive for human T-cell lymphotropic virus types I or II and those with untreated brucellosis. Women should not breastfeed if they have active tuberculosis (TB) or if they have active herpes simplex lesions on the breasts. However, neither of these conditions precludes a mother expressing milk for her infant (AAP Section on Breastfeeding, 2012). Women with active TB can breastfeed when they have been treated for at least 2 weeks and are deemed noninfectious. Varicella that occurs 5 days before or 2 days after birth and acute H1N1 infection require temporary separation of mother and infant. In both instances it is safe for infants to receive expressed milk (AAP Section on Breastfeeding, 2012). In the United States maternal human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is considered a contraindication for breastfeeding (AAP Section on Breastfeeding, 2012). However, that is not true in other countries. In developing countries where HIV is prevalent, the benefits of breastfeeding for infants outweigh the risk of contracting HIV from infected mothers (WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, and UNAIDS, 2010). Breastfeeding is not recommended when mothers are receiving chemotherapy or radioactive isotopes (e.g., with diagnostic procedures). Maternal use of mood-altering drugs (“street drugs”) is incompatible with breastfeeding (AAP Section on Breastfeeding, 2012). Other maternal medications may also be incompatible with and require temporary or permanent cessation of breastfeeding. In general people who have immigrated to the United States from poorer countries often choose to formula feed their infants because they believe it is a better, more “modern” method or because they want to adapt to U.S. culture and perceive that formula feeding is the custom. Hispanic women who are more acculturated may be less likely to breastfeed and, if they do, tend to breastfeed for a shorter duration (Ahluwalia, D’Angelo, Morrow, et al., 2012). A common practice among Mexican women is las dos cosas (“both things”). This refers to combining breastfeeding and commercial infant formula. It is based on the belief that, by combining the two methods, the mother and infant receive the benefits of breastfeeding, and the infant receives the additional vitamins from infant formula (Bartick and Reyes, 2012; Rios, 2009). This practice can result in problems with milk supply and babies refusing to latch on to the breast, which can lead to early termination of breastfeeding. During the first 2 days of life the fluid requirement for healthy infants (more than 1500 g) is 60 to 80 mL of water per kilogram of body weight per day. From day 3 to 7 the requirement is 100 to 150 mL/kg/day; from day 8 to day 30 it is 120 to 180 mL/kg/day (Dell, 2011). In general neither breastfed nor formula-fed infants need to be given water, not even those living in very hot climates. Breast milk contains 87% water, which easily meets fluid requirements. Feeding water to infants can decrease caloric consumption at a time when they are growing rapidly. Infants require adequate caloric intake to provide energy for growth, digestion, physical activity, and maintenance of organ metabolic function. Energy needs vary according to age, maturity level, thermal environment, growth rate, health status, and activity level. For the first 3 months the infant needs 110 kcal/kg/day. From 3 months to 6 months the requirement is 100 kcal/kg/day. This level decreases slightly to 95 kcal/kg/day from 6 to 9 months and increases to 100 kcal/kg/day from 9 months to 1 year (AAP Committee on Nutrition, 2009). According to the Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2005), the recommended adequate intake (AI) for carbohydrates in the first 6 months of life is 60 g/day and 95 g/day for the second 6 months. Because newborns have only small hepatic glycogen stores, carbohydrates should provide at least 40% to 50% of the total calories in the diet. Moreover newborns may have a limited ability to carry out gluconeogenesis (the formation of glucose from amino acids and other substrates) and ketogenesis (the formation of ketone bodies from fat), the mechanisms that provide alternative sources of energy. Fats provide a major energy source for infants, supplying as much as 50% of the calories in breast milk and formula. The recommended AI of fat for infants younger than 6 months is 31 g/day (IOM, 2005). The fat content of human milk is composed of lipids, triglycerides, and cholesterol; cholesterol is an essential element for brain growth. Human milk contains the essential fatty acids (EFAs) linoleic acid and linolenic acid and the long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids arachidonic acid (ARA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Fatty acids are important for growth, neurologic development, and visual function. Cow’s milk contains fewer of the EFAs and no polyunsaturated fatty acids. Most formula companies add DHA to their products, although there is a lack of evidence supporting the benefit (Lawrence and Lawrence, 2011b). Modified cow’s milk is used in most infant formulas; but the milk fat is removed, and another fat source such as corn oil, which the infant can digest and absorb, is added in its place. If whole milk or evaporated milk without added carbohydrate is fed to infants, the resulting fecal loss of fat (and therefore loss of energy) can be excessive because the milk moves through the infant’s intestines too quickly for adequate absorption to take place. This can lead to poor weight gain. High-quality protein from breast milk, infant formula, or other complementary foods is necessary for infant growth. The protein requirement per unit of body weight is greater in the newborn than at any other time of life. For infants younger than 6 months the recommended AI for protein is 9.1 g/day (IOM, 2005). Human milk contains the two proteins whey and casein in a ratio of approximately 70 : 30 compared with the ratio of 20 : 80 in most cow’s milk–based formula (Blackburn, 2013). This whey/casein ratio in human milk makes it more easily digestible and produces the soft stools seen in breastfed infants. The primary whey protein in human milk is α-lactalbumin; this protein is high in essential amino acids needed for growth. The whey protein lactoferrin in human milk has iron-binding capabilities and bacteriostatic properties, particularly against gram-positive and gram-negative aerobes, anaerobes, and yeasts. The casein in human milk enhances the absorption of iron, thus preventing iron-dependent bacteria from proliferating in the GI tract (Lawrence and Lawrence, 2011a). The amino acid components of human milk are uniquely suited to the newborn’s metabolic capabilities. For example, cystine and taurine levels are high, whereas phenylalanine and methionine levels are low. Vitamin D facilitates intestinal absorption of calcium and phosphorus, bone mineralization, and calcium resorption from bone. According to the AAP, all infants who are breastfed or partially breastfed should receive 400 International Units of vitamin D daily, beginning the first few days of life. Nonbreastfeeding infants and older children who consume less than 1 quart per day of vitamin D–fortified milk should also receive 400 International Units of vitamin D each day (Wagner, Grier, and AAP Section on Breastfeeding and Committee on Nutrition, 2008). Vitamin K, required for blood coagulation, is produced by intestinal bacteria. However, the gut is sterile at birth, and a few days are required for intestinal flora to become established and produce vitamin K. To prevent hemorrhagic problems in the newborn an injection of vitamin K is given at birth to all newborns, regardless of feeding method (AAP Section on Breastfeeding, 2012). Iron levels are low in all types of milk; however, iron from human milk is better absorbed than iron from cow’s milk, iron-fortified formula, or infant cereals. Breastfed infants draw on iron reserves deposited in utero and benefit from the high lactose and vitamin C levels in human milk that facilitate iron absorption. Full-term infants have enough iron stores from the mother to last for the first 4 months. After 4 months of age, infants who are exclusively breastfed are at risk for iron deficiency. The AAP recommends giving exclusively breastfed infants an iron supplement (1 mg/kg/day) beginning at 4 months and continuing until the infant is consuming iron-containing complementary foods such as iron-fortified cereals. Infants who are partially breastfed should receive the same iron supplement if more than half of their daily feedings consists of human milk and they are not consuming iron-rich foods (Baker, Greer, and the AAP Committee on Nutrition, 2010). Formula-feeding infants should receive an iron-fortified commercial infant formula until 12 months of age. Infants younger than 1 year should never be fed whole milk (Baker, Greer, and the AAP Committee on Nutrition, 2010). Fluoride levels in human milk and commercial formulas are low. This mineral, which is important in preventing dental caries, can cause spotting of the permanent teeth (fluorosis) in excess amounts. Experts recommend that no fluoride supplements be given to infants younger than 6 months. From 6 months to 3 years, fluoride supplements are based on the concentration of fluoride in the water supply (AAP Section on Breastfeeding, 2012). Each female breast is composed of approximately 15 to 20 segments (lobes) embedded in fat and connective tissues and well supplied with blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerves (Fig. 24-1). Within each lobe is glandular tissue consisting of alveoli, the milk-producing cells, surrounded by myoepithelial cells that contract to send the milk forward to the nipple during milk ejection. Each nipple has multiple pores that transfer milk to the suckling infant. The ratio of glandular to adipose tissue in the lactating breast is approximately 2 : 1 compared with a 1 : 1 ratio in the nonlactating breast. Within each breast is a complex, intertwining network of milk ducts that transport milk from the alveoli to the nipple. The milk ducts dilate and expand at milk ejection. Previous thinking held that the milk ducts converged behind the nipple in lactiferous sinuses, which acted as reservoirs for milk. However, research based on ultrasonography of lactating breasts has shown that these sinuses do not exist and, in fact, glandular tissue can be found directly beneath the nipple (Geddes, 2007; Ramsay, Kent, Hartmann, et al., 2005) (Fig. 24-2). After the mother gives birth a precipitous fall in progesterone triggers the release of prolactin from the anterior pituitary gland. During pregnancy prolactin prepares the breasts to secrete milk and during lactation to synthesize and secrete milk. Prolactin levels are highest during the first 10 days after birth, gradually declining over time but remaining above baseline levels for the duration of lactation. Prolactin is produced in response to infant suckling and emptying of the breasts (Fig. 24-3, A). Milk production is a supply-meets-demand system (i.e., as milk is removed from the breast, more is produced). Incomplete removal of milk from the breasts can lead to decreased milk supply. Oxytocin is essential to lactation. As the nipple is stimulated by the suckling infant, the posterior pituitary is prompted by the hypothalamus to produce oxytocin. This hormone is responsible for the milk ejection reflex (MER), or let-down reflex (see Fig. 24-3, B). The myoepithelial cells surrounding the alveoli respond to oxytocin by contracting and sending the milk forward through the ducts to the nipple. The MER is triggered multiple times during a feeding session. Thoughts, sights, sounds, or odors that the mother associates with her baby (or other babies) such as hearing the baby cry can trigger the MER. Many women report a tingling “pins and needles” sensation in the breasts as milk ejection occurs, although some mothers can detect milk ejection only by observing the sucking and swallowing of the infant. The MER also can occur during sexual activity because oxytocin is released during orgasm. The reflex can be inhibited by fear, stress, and alcohol consumption. Human milk contains immunologically active components that provide some protection against a broad spectrum of bacterial, viral, and protozoal infections. The major immunoglobulin (Ig) in human milk is secretory IgA; IgG, IgM, IgD, and IgE are also present. Human milk also contains T and B lymphocytes, epidermal growth factor, cytokines, interleukins, bifidus factor, complement (C3 and C4), and lactoferrin, all of which have a specific role in preventing localized and systemic bacterial and viral infections (Lawrence and Lawrence, 2011a). Human milk composition and volumes vary according to the stage of lactation. In lactogenesis stage I, beginning at approximately 16 to 18 weeks of pregnancy, the breasts are preparing for milk production by producing prepartum milk or colostrum. Stage II of lactogenesis begins with birth as progesterone levels drop sharply when the placenta is removed. For the first 2 to 3 days after birth, the baby receives colostrum, a clear, yellowish fluid that is rich in antibodies and higher in protein but lower in fat than mature milk. The high protein level of colostrum facilitates binding of bilirubin, and the laxative action of colostrum promotes early passage of meconium. Colostrum is important in the establishment of normal Lactobacillus bifidus flora in the infant’s digestive tract. It gradually changes to transitional milk. By 3 to 5 days after birth the woman experiences a noticeable increase in milk production. This is often referred to as the milk coming in. Breast milk continues to change in composition for approximately 10 days, when the mature milk is established. This is stage III of lactogenesis (Lawrence and Lawrence, 2011a). The composition of human milk changes over time as the infant grows and develops. Fat is the most variable component of human milk with changes in concentration over a feeding, over a 24-hour period, and across time. Variations in fat content exist between breasts and among individuals (Lawrence and Lawrence, 2011a). During each feeding the concentration of fat gradually increases from the lower fat foremilk to the richer hindmilk. The hindmilk contains the denser calories from fat necessary for ensuring optimal growth and contentment between feedings. Because of this changing composition of human milk during each feeding, breastfeeding the infant long enough to supply a balanced feeding is important. Connecting expectant mothers with women from similar backgrounds who are breastfeeding or have successfully breastfed is often helpful. Nursing mothers’ support groups such as La Leche League or Mocha Moms provide information about breastfeeding along with opportunities for breastfeeding mothers to interact with one another and share concerns (Fig. 24-4). Peer counseling programs such as those instituted by WIC are beneficial. Promoting feelings of competence and confidence in the breastfeeding mother and reinforcing the unequaled contribution she is making toward the health and well-being of her infant are the responsibility of the nurse and other health care professionals. The first 2 weeks of breastfeeding can be the most challenging as mothers are adjusting to life with a newborn, the baby is learning to latch on and feed effectively, and the mother may be experiencing nipple or breast discomfort. This is a time when support is critical. Primiparous women are most likely to experience early breastfeeding problems, which often result in less exclusive breastfeeding and shorter duration of breastfeeding (Chantry, 2011). Anticipatory guidance during the prenatal period and especially during the hospital stay after birth can provide the mother with information and increase her confidence in her ability to successfully breastfeed her infant. New mothers need access to lactation support following discharge through primary care offices or outpatient lactation services. Peer support is also helpful. The most common reasons for breastfeeding cessation are insufficient milk supply, painful nipples, and problems getting the infant to feed (Lauwers and Swisher, 2011; Lawrence and Lawrence, 2011a). Early and ongoing assistance and support from health care professionals to prevent and address problems with breastfeeding can help promote a successful and satisfying breastfeeding experience for mothers and infants. Many health care agencies have certified lactation consultants on staff. These health care professionals, who are usually nurses, have specialized training and experience in helping breastfeeding mothers and infants. The U.S. Breastfeeding Committee (USBC, 2010a) has identified key competencies for health care professionals related to breastfeeding care and services. The competencies include knowledge, skills, and attitudes to promote and support breastfeeding. The USBC identifies specific competencies for those who provide more “hands-on” care (e.g., nurses and lactation consultants). The competencies are: “assist in early initiation of breastfeeding, assess the lactating breast, perform an infant feeding observation, recognize normal and abnormal infant feeding patterns, and develop and appropriately communicate a breastfeeding care plan” (USBC, 2010a, p. 5). All parents are entitled to a birthing environment in which breastfeeding is promoted and supported. The Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI), sponsored by the WHO and UNICEF, was founded in 1991 to encourage institutions to offer optimal levels of care for lactating mothers. When a hospital achieves the “Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding for Hospitals,” it is recognized as a Baby-Friendly hospital (Box 24-1) (BFHI USA, 2010). In 2009 only 6.2% of live births in the United States occurred at Baby-Friendly facilities (CDC, 2012). More than 19,000 facilities worldwide have achieved Baby-Friendly status. As of May 2012 143 health care facilities in the United States were designated as Baby-Friendly (BFHI USA, 2012), although many hospitals and birthing facilities are working toward reaching that goal. Women are more likely to achieve their goals for exclusive breastfeeding if they give birth in facilities where all or most of the ten steps are in place (Declercq, Labbok, Sakala, et al., 2009; Perrine, Scanlon, Li, et al., 2012). The Joint Commission (TJC) issued a set of Perinatal Core Measures that includes exclusive breast milk feeding. In implementing the core measures, hospitals strive to improve their adherence to evidence-based best practices that can result in increased rates of exclusive breastfeeding (TJC, 2012; USBC, 2010b). Care management of the breastfeeding mother and infant requires that nurses and other health care professionals be knowledgeable about the benefits and basic anatomic and physiologic aspects of breastfeeding. They also need to know how to help the mother with feedings and discuss interventions for common problems. Ongoing support of the mother enhances her self-confidence and promotes a satisfying and successful breastfeeding experience. Mothers should be encouraged to ask for help with breastfeeding, especially while they are in the hospital. Primiparas are likely to need the most assistance and in many facilities are routinely seen by lactation consultants. The mother needs to understand infant behaviors in relation to breastfeeding and recognize signs that the baby is ready to feed. Infants exhibit feeding-readiness cues or early signs of hunger. Instead of waiting to feed until the infant is crying in a distraught manner or withdrawing into sleep, the mother should attempt to breastfeed when the baby exhibits feeding cues (see Evidence-Based Practice box): • Hand-to-mouth or hand-to-hand movements • Rooting reflex—infant moves toward whatever touches the area around the mouth and attempts to suck Babies normally consume small amounts of milk with feedings during the first 3 days of life. As the baby adjusts to extrauterine life and the digestive tract is cleared of meconium, milk intake increases from 15 to 30 mL per feeding in the first 24 hours to 60 to 90 mL by the end of the first week. The ideal time to begin breastfeeding is within the first hour after birth (BFHI, 2010). Newborns without complications should be allowed to remain in direct skin-to-skin contact with the mother until the baby is able to breastfeed for the first time (AAP Section on Breastfeeding, 2012). This is true both for mothers who gave birth by cesarean and for those who gave birth vaginally. Early skin-to-skin contact is associated with higher rates of exclusive breastfeeding while in the hospital (Bramson, Lee, Moore, et al., 2010) and increased duration of breastfeeding (Moore, Anderson, Bergman, et al., 2012). Routine procedures such as vitamin K injection, eye prophylaxis, weighing, and bathing should be delayed until the neonate has completed the first feeding (AAP Section on Breastfeeding, 2012). For the initial feedings it can be advantageous to encourage and assist the mother to breastfeed in a semireclining position with the newborn lying prone, skin-to-skin on the mother’s bare chest. Her body supports the baby. The mother is more relaxed, nipple pain is reduced or eliminated, and the mother has more freedom of movement to use her hands. The baby is able to use inborn reflexes to latch onto the breast and feed effectively. This approach to breastfeeding is based on the concept of “biological nurturing” (Colson, 2010, 2012). The four traditional positions for breastfeeding are the football or clutch hold (under the arm), modified cradle or across-the-lap, cradle, and side-lying (Fig. 24-5). The mother should be encouraged to use the position that most easily facilitates latch while allowing maximal comfort. The football or clutch hold is often recommended for early feedings because the mother can see the baby’s mouth easily as she guides the infant onto the nipple.

Newborn Nutrition and Feeding

Recommended Infant Nutrition

Breastfeeding Rates

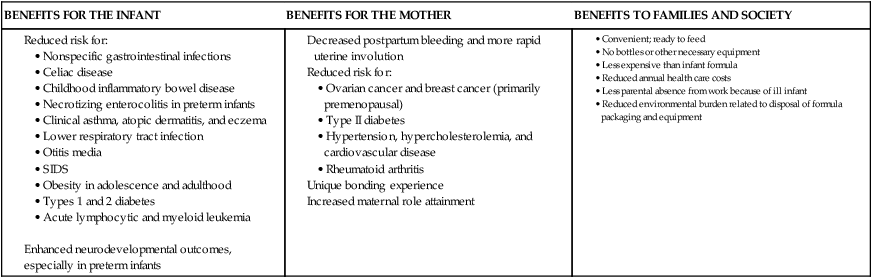

Benefits of Breastfeeding

BENEFITS FOR THE INFANT

BENEFITS FOR THE MOTHER

BENEFITS TO FAMILIES AND SOCIETY

Enhanced neurodevelopmental outcomes, especially in preterm infants

Choosing an Infant Feeding Method

Choosing to Breastfeed

Choosing to Formula Feed

Contraindications to Breastfeeding

Cultural Influences on Infant Feeding

Nutrient Needs

Fluids

Energy

Carbohydrates

Fat

Protein

Vitamins

Minerals

Breastfeeding

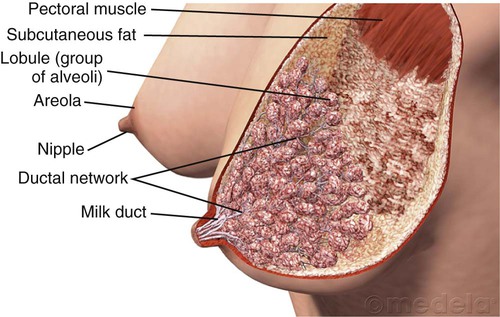

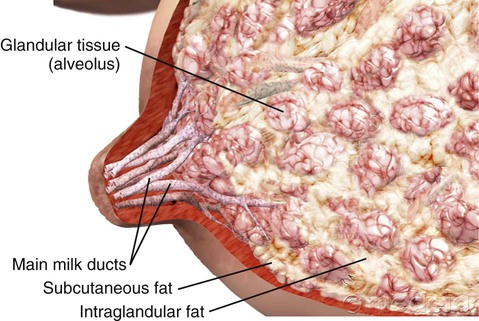

Anatomy of the Lactating Breast

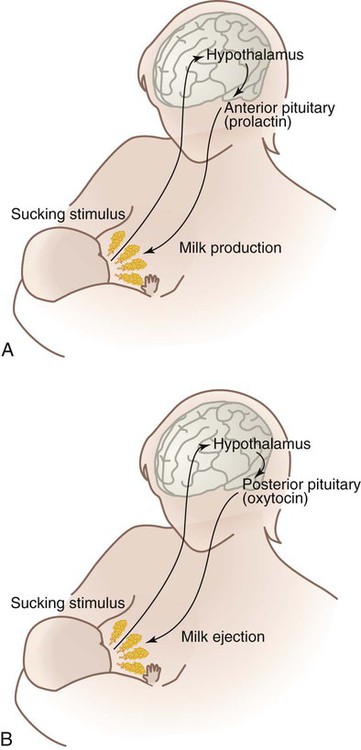

Lactogenesis

Uniqueness of Human Milk

Care Management

Supporting Breastfeeding Mothers and Infants

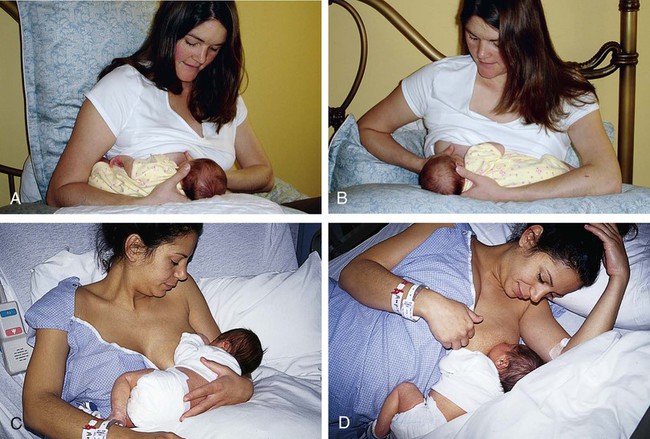

Positioning

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Newborn Nutrition and Feeding

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access