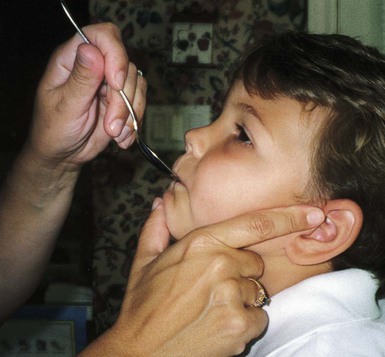

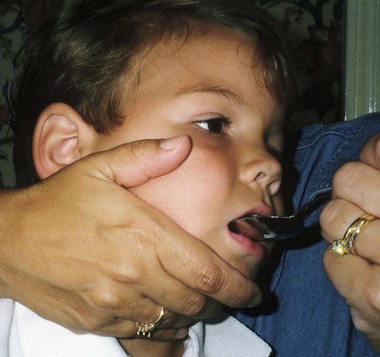

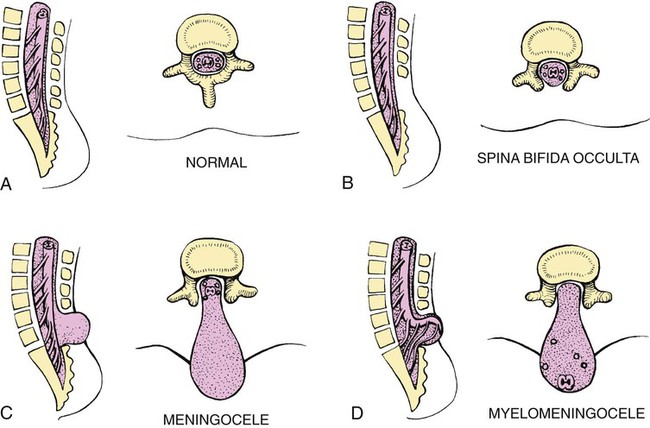

On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Discuss the nursing role in helping parents care for the child with cerebral palsy. • Formulate a nursing care plan for the preoperative and postoperative care of a child with myelomeningocele (spina bifida). • Outline a plan of care for a child with Duchenne or Becker muscular dystrophy. • Discuss the prevention and treatment of tetanus. • Identify the causes of botulism in infants and children. • List three causes of spinal cord injury in children. • Discuss the emergent nursing care of the child or adolescent with a spinal cord injury. Cerebral palsy (CP) has been defined as a “group of permanent disorders of the development of movement and posture, causing activity limitation, that are attributed to nonprogressive disturbances that occurred in the developing fetal or infant brain” (Rosenbaum, Paneth, Leviton, et al., 2007). In addition to motor disorders, the condition often involves disturbances of sensation, perception, communication, cognition, and behavior; secondary musculoskeletal problems; and epilepsy (Rosenbaum, Paneth, Leviton, et al., 2007). The etiology, clinical features, and course vary and are characterized by abnormal muscle tone and coordination as the primary disturbances. CP is the most common permanent physical disability of childhood, and the incidence is reported to be between 2.4 and 3.6 per every 1000 live births in the United States (Hirtz, Thurman, Gwinn-Hardy, et al., 2007; Yeargin-Allsopp, Van Naarden Braun, Doernberg, et al., 2008). Prevalence of CP among extremely low-birth-weight infants (less than 28 weeks’ gestation) is said to be nearly 100 times the rate in term infants; however, these rates reportedly have declined in recent years (O’Shea, 2008). CP is currently believed to result more often from existing prenatal brain abnormalities; the exact cause of these abnormalities remains elusive but may include genetic factors, including clotting disorders as well as brain malformations. It has been estimated that as many as 80% of CP cases are attributable to unidentified prenatal factors (Johnston, 2011; Krigger, 2006). Intrauterine exposure to maternal chorioamnionitis is associated with an increased risk for CP in infants of normal birth weight and preterm infants (Hermansen and Hermansen, 2006); however, not all term infants exposed to chorioamnionitis develop CP (Grether, Nelson, Walsh, et al., 2003; Wu, Escobar, Grether, et al., 2003). Perinatal ischemic stroke is also associated with a later diagnosis of CP (Golomb, Saha, Garg, et al., 2007). One study found a higher risk for CP occurring among infants born at 42 weeks’ gestation or later than among those born at 37 or 38 weeks’ gestation (Moster, Wilcox, Vollset, et al., 2010). Additional factors that may contribute to the development of CP postnatally include bacterial meningitis, multiple births, viral encephalitis, motor vehicle crashes (MVCs), and child abuse (shaken baby syndrome [traumatic brain injury]). A significant percentage (15% to 60%) of children with CP also have epilepsy. In summary, as many as 80% of the total cases of CP may be linked to a perinatal or neonatal brain lesion or brain maldevelopment, regardless of the cause (Krageloh-Mann and Cans, 2009). There are a few exceptions. In some cases, the manifestations or etiology is related to anatomic areas. For example, CP associated with preterm birth is usually spastic diplegia caused by hypoxic infarction or hemorrhage with periventricular leukomalacia in the area adjacent to the lateral ventricles. The athetoid (extrapyramidal) type of CP is most likely to be associated with birth asphyxia but can also be caused by kernicterus and metabolic genetic disorders such as mitochondrial disorders and glutaricaciduria (Johnston, 2011). Hemiplegic (hemiparetic) CP is often associated with a focal cerebral infarction (stroke) secondary to an intrauterine or perinatal thromboembolism, usually a result of maternal thrombosis or hereditary clotting disorder (Johnston, 2011). Cerebral hypoplasia and sometimes severe neonatal hypoglycemia are related to ataxic CP. Generalized cortical and cerebral atrophy often cause severe quadriparesis with cognitive impairment and microcephaly. A revision of the Winter classification was proposed in 2005 to reflect the child’s actual clinical problems and their severity, an assessment of the child’s physical and quality-of-life status across time, and long-term support needs (Bax, Goldstein, Rosenbaum, et al., 2005; Nehring, 2010). The proposed new definition has four major dimensions of classification (Bax, Goldstein, Rosenbaum, et al., 2005): Motor abnormalities—Nature and typology of the motor disorder; functional motor abilities Associated impairments—Seizures; hearing or vision impairment; attentional, behavioral, communicative, or cognitive deficits; oral motor and speech function Anatomic and radiologic findings—Anatomic distribution or parts of the body affected by motor impairments or limitations; radiologic findings sometimes including white matter lesions or brain anomaly noted on computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) Causation and timing—Identification of a clearly identified cause such as a postnatal event (e.g., meningitis, traumatic brain injury) Cerebral palsy has four primary types of movement disorders: spastic, dyskinetic, ataxic, and mixed (Nehring, 2010). The most common clinical type, spastic CP, represents an upper motor neuron muscular weakness (Box 49-1). The reflex arc is intact, and the characteristic physical signs are increased stretch reflexes, increased muscle tone, and (often) weakness. Early neurologic manifestations are usually generalized hypotonia or decreased tone that lasts for a few weeks or may extend for months or even as long as 1 year. Early recognition is made more difficult by the lack of reliable neonatal neurologic signs. However, nurses should monitor infants with known etiologic risk factors and evaluate them closely in the first 2 years of life. Because cortical control of movement does not occur until later in infancy, motor impairment associated with voluntary control is usually not apparent until after 2 to 4 months of age at the earliest. More often, the diagnosis cannot be confirmed until the age of 2 years because motor tone abnormalities may be indicative of another neuromuscular illness. In addition, some children who show signs consistent with CP before 2 years do not demonstrate such signs after 2 years (Nehring, 2010). However, there is no consensus regarding an age cut-off for the onset of symptoms. Clinical manifestations of CP at the time of diagnosis are listed in Box 49-2; early warning signs are listed in Box 49-3, but these are not considered diagnostic. 1. To establish locomotion, communication, and self-help skills 2. To gain optimal appearance and integration of motor functions 3. To correct associated defects as effectively as possible 4. To provide educational opportunities adapted to the child’s needs and capabilities 5. To promote socialization experiences with other affected and unaffected children Each child is evaluated and managed on an individual basis. The scope of the child’s needs requires multidisciplinary planning and care coordination among health care professionals and the child’s family. The outcome for the child and family with CP is normalization and promotion of self-care activities that empower the child and family to achieve maximum potential. Ankle-foot orthoses (AFOs, braces) are worn by many children with CP and are used to help prevent or reduce deformity, increase the energy efficiency of gait, and control alignment. Wheeled go-carts that provide sitting balance may serve as early “wheelchair” experience for young children. Manual or powered wheelchairs allow for more independent mobility (Figs. 49-1 and 49-2). Strollers can be equipped with custom seats for dependent mobilization. Botulinum toxin A (Botox) is also used to reduce spasticity in targeted muscles, primarily those of the upper and lower extremities. Botulinum toxin A is injected into a selected muscle (commonly the quadriceps, gastrocnemius, or medial hamstrings) after a topical anesthetic is applied. The drug acts to inhibit the release of acetylcholine into a specific muscle group, thereby preventing muscle movement. When it is administered early in the course of the condition, affected muscle contractures may be minimized, particularly in lower extremities, thus avoiding surgical procedures with possible adverse effects. The goal is to allow stretching of the muscle as it relaxes and permit ambulation with an AFO. The major reported adverse effects of botulinum toxin A injection are pain at the injection site and temporary weakness (Lukban, Rosales, and Dressler, 2009). Prime candidates for botulinum toxin A injections are children with spasticity confined to the lower extremities; the drug weakens spasticity so the muscles can be stretched and the child may walk with or without orthoses. The onset of action occurs within 24 to 72 hours, with a peak effect observed at 2 weeks and a duration of action of 3 to 6 months. Diazepam has proved effective on a short-term basis in reducing spasticity in children with CP (Delgado, Hirtz, Aisen, et al., 2010). The neurosurgical and pharmacologic approach to relieving the spasticity associated with CP involves the implantation of a pump to infuse baclofen directly into the intrathecal space surrounding the spinal cord. Intrathecal baclofen therapy is best suited for children with severe spasticity that interferes with activities of daily living (ADLs) and ambulation; however, this drug and method of administration (intrathecal) have had a significant number of adverse or side effects (Delgado, Hirtz, Aisen, et al., 2010). Patients may be screened before pump placement by the infusion of a “test dose” of intrathecal baclofen delivered via a lumbar puncture, followed by close monitoring for side effects (hypotonia, somnolence, seizures, nausea, vomiting, headache). Relief of spasticity occurs for several hours after the infusion. If a positive effect is noted, the patient is considered a candidate for pump placement. The implantation procedure is done in the operating room by a neurosurgeon. The pump, which is approximately the size of a hockey puck, is placed in the subcutaneous space of the midabdomen. An intrathecal catheter is tunneled from the lumbar area to the abdomen and connected to the pump. The pump is filled with baclofen and programmed to provide a set dose using a telemetry wand and a computer. Benefits of intrathecal baclofen include fewer systemic side effects than oral baclofen, dosage titration for maximizing effects, and reversibility of therapy with removal of the pump if so desired. The patient may remain hospitalized for 3 to 7 days to adjust the dosage and ensure proper healing. Outpatient visits to refill the pump and make dosage adjustments occur about every 3 to 6 months, depending on the patient’s response to the treatment. This procedure is most suited for a multidisciplinary setting where rehabilitation specialists are readily available and consistently involved in the patient’s ongoing care. Abrupt withdrawal of intrathecal baclofen may result in adverse effects such as rebound spasticity, pruritus, hyperthermia, rhabdomyolysis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, multiorgan failure, and death; in some cases, intrathecal baclofen withdrawal may mimic sepsis. Oral baclofen has also been widely used in children with CP to treat spasticity; however, side effects are common and include systemic toxicity, drowsiness, and sedation (Delgado, Hirtz, Aisen, et al., 2010). Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) such as carbamazepine (Tegretol) and divalproex (valproate sodium and valproic acid; Depakote) are prescribed routinely for children who have seizures. Gabapentin (Neurontin) has been used in adults with spinal cord injury (SCI) to decrease spasticity with success; no studies are available on the effectiveness of the drug in children. The α2-adrenergic agonists clonidine (Catapres) and tizanidine (Zanaflex) have been used to decrease spasticity in adults with SCI and multiple sclerosis. The use of oral tizanidine in children has been limited, and only a few small studies have been conducted in children with CP specifically evaluating the reduction of spasticity (Delgado, Hirtz, Aisen, et al., 2010). Oral tizanidine given in conjunction with botulinum type A has been reported to be more effective than oral baclofen and botulinum type A in one study of children with CP (Dai, Wasay, and Awan, 2008). All medications should be monitored for maintenance of therapeutic levels and avoidance of subtherapeutic or toxic levels. Other medications include levodopa to treat dystonia; Artane for treating dystonia and for increasing the use of upper extremities and vocalizations; and reserpine for hyperkinetic movement disorders such as chorea or athetosis (Johnston, 2011). There is some evidence that neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) in addition to dynamic splinting may result in increased muscle strength, range of motion, and function of upper limbs in children with CP. Further studies are needed in children with CP to support the use of botulinum toxin A in conjunction with NMES to decrease muscle spasticity and improve function (Wright, Durham, Ewins, et al., 2012). Behavior problems may occur and often interfere with the child’s development. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and other learning problems require professional attention. In addition, children with CP may have vision difficulties such as strabismus, nystagmus, and optic atrophy (Johnston, 2011). Speech-language therapy involves the services of a speech-language pathologist who may also assist with feeding problems. The prognosis for the child with CP depends largely on the type and severity of the condition. Children with mild to moderate involvement (85%) have the capability of achieving ambulation between the ages of 2 and 7 years (Berker and Yalçin, 2008). If the child does not achieve independent ambulation by this time, chances are poor for ambulation and independence. Approximately 30% to 50% of individuals with CP have significant cognitive impairments, and an even higher percentage have mild cognitive and learning deficits. However, many children with severe spastic tetraplegic CP have normal intelligence. Growth is affected in children with spastic tetraplegia, and many children remain below the 5th percentile for age and gender. Vocational rehabilitation and higher education are possible for adults with CP. Children with severe CP mobility impairment and feeding problems often succumb to respiratory tract infection in childhood (Liptak, Murphy, and Council on Children with Disabilities, 2011). The few survival rate studies on children and adults with CP show that survival is influenced by existing comorbidities (Nehring, 2010). Neurorehabilitation involves rehabilitating and stimulating nerves (that control muscle movement) that have been damaged to improve brain development; brain plasticity is being examined closely as a possible avenue for reorganizing traditionally damaged neural pathways to function optimally for children with CP. Children with CP or SCI may benefit from therapies such as constraint-induced movement therapy wherein a stronger extremity is constrained to force the weaker extremity to function; these treatments have shown improvement in some children with CP (Aisen, Kerkovich, Mast, et al., 2011). Prevention of CP in many children may become a reality in the near future. Studies indicate that early neuroprotection in term infants with the use of therapeutic hypothermia (head cooling or whole-body cooling) within 6 hours of birth improved survival without CP by approximately 40% (Johnston, Fatemi, Wilson, et al., 2011). More recent studies have found lower death rates and less severe disability with the use of therapeutic hypothermia, but overall intelligence quotient (IQ) scores at 6 to 7 years of age were not statistically significant in those receiving hypothermia (as compared with those receiving conventional treatment) (Shankaran, Pappas, McDonald, et al., 2012). Because children with CP are being identified and treated at an earlier age, parents are participating earlier in treatment programs for their children with disabilities. They are taught the proper handling and home care of young children with CP and need a carefully planned program so that their change of role from parent to caregiver can be melded into the already established relationship. Close work with other multidisciplinary team members is essential. Nurses reinforce the therapeutic plan and assist the family in devising and modifying equipment and activities to continue the therapy program in the home. The nursing process in the care of the child with CP is outlined in the Nursing Care Plan. A skin-level gastrostomy is particularly suited for children with CP. Parents may need assistance and advice with medication administration through a gastrostomy tube to prevent clogging. Because jaw control is often compromised, more normal control can be achieved if the feeder provides stability of the oral mechanism from the side or front of the face. When directed from the front, the middle finger of the nonfeeding hand is placed posterior to the body portion of the chin, the thumb is placed below the bottom lip, and the index finger is placed parallel to the child’s mandible (Fig. 49-3). Manual jaw control from the side assists with head control, correction of neck and trunk hyperextension, and jaw stabilization. The middle finger of the nonfeeding hand is placed posterior to the bony portion of the chin, the index finger is placed on the chin below the lower lip, and the thumb is placed obliquely across the cheek to provide lateral jaw stability (Fig. 49-4). Safety precautions are implemented, such as having children wear protective helmets if they are subject to falls or capable of injuring their heads on hard objects. Because children with CP are at risk for altered proprioception and subsequent falls, the home and play environment should be adapted to their needs to prevent bodily harm. Appropriate immunizations should be administered to prevent childhood illnesses and protect against respiratory tract infections such as influenza and pneumonia. Dental problems may be more common in children with CP, which creates a need for meticulous attention to all aspects of dental care. Transportation of the child with motor problems and restricted mobility may be especially challenging for the family and child. Attention must be given to the child’s safety when riding in a motor vehicle; a federally approved safety restraint should be used at all times. It is recommended that children with CP ride in a rear-facing position as long as possible because of their poor head, neck, and trunk control (Lovette, 2008). Car restraints especially designated for children with poor head and neck control are available and should be used.* Probably the nursing interventions most valuable to the family are support and help in coping with the emotional aspects of the disorder, many of which are discussed in relation to the child with a disability (see Chapter 36). Initially, the parents need supportive counseling directed toward understanding the meaning of the diagnosis and all of the feelings that it engenders. Later, they need clarification regarding what they can expect from the child and from health care professionals. Educating families in the principles of family-centered care and parent-professional collaboration is essential. The family may require help in modifying the home environment for care of the child. Home modifications to facilitate the use of a wheelchair may be necessary. The child or adolescent should be encouraged to be as independent as possible; making necessary home modifications to facilitate the child’s independence is strongly encouraged. Transportation to the health care practitioner’s office and other health care agencies also requires special arrangements. The home health care nurse should be consulted for assistance in making the home environment accessible to the child or adolescent with CP. Parents may also find help and comfort from parent groups, with whom they can share challenges and concerns and from whom they can derive comfort and practical information. Parent support groups are most helpful through sharing experiences and accomplishments. For example, parents can learn from others what it is like to have a child with CP, which is generally not possible from professionals (see Family-Centered Care box). The national organization United Cerebral Palsy* has branches in most communities. The association provides a variety of services for children and families. A number of excellent books also are available to guide parents and nurses who work with children with CP. Abnormalities that derive from the embryonic neural tube (neural tube defects [NTDs]) constitute the largest group of congenital anomalies that are consistent with multifactorial inheritance. Normally, the spinal cord and cauda equina are encased in a protective sheath of bone and meninges (Fig. 49-5, A). Failure of neural tube closure produces defects of varying degrees (Box 49-4). They may involve the entire length of the neural tube or may be restricted to a small area. In the United States, rates of NTDs have declined from 1.3 per 1000 births in 1970 to 0.3 per 1000 births after the introduction of mandatory food fortification with folic acid in 1998. One concern is that NTD rates have not decreased among Hispanic and non-Hispanic Caucasian mothers since 1999 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2009). In 2005, the rates for spina bifida were estimated by the CDC to be 17.96 per 100,000 live births, thus making this one of the most common birth defects in the United States (Matthews, 2009; Wolff, Witkop, Miller, et al., 2009). Increased use of prenatal diagnostic techniques and termination of pregnancies have also affected the overall incidence of NTDs (see also Prevention, p. 1582). Spina bifida occulta refers to a defect that is not visible externally. It occurs most frequently in the lumbosacral area (L5 and S1) (see Fig. 49-5, B). SB occulta may not be apparent unless there are associated cutaneous manifestations or neuromuscular disturbances. Spina bifida cystica refers to a visible defect with an external saclike protrusion. The two major forms of SB cystica are meningocele, which encases meninges and spinal fluid but no neural elements (see Fig. 49-5, C), and myelomeningocele (MMC) (or meningomyelocele), which contains meninges, spinal fluid, and nerves (see Fig. 49-5, D). Meningocele is not associated with neurologic deficit, which occurs in varying, often serious, degrees in myelomeningocele. Clinically, the term spina bifida is used to refer to myelomeningocele. There is evidence of a multifactorial etiology, including drugs, radiation, maternal malnutrition, chemicals, and possibly a genetic mutation in folate pathways in some cases, which may result in abnormal development. There is also evidence of a genetic component in the development of SB; myelomeningocele may occur in association with syndromes such as trisomy 18, PHAVER (limb pterygia, congenital heart anomalies, vertebral defects, ear anomalies, and radial defects) syndrome, and Meckel-Gruber syndrome (Shaer, Chescheir, and Schulkin, 2007). Additional factors predisposing children to an increased risk for NTDs include prepregnancy maternal obesity, maternal diabetes mellitus, low maternal vitamin B12 status, maternal hyperthermia, and the use of AEDs in pregnancy. The genetic predisposition is supported by evidence of the risk for recurrence after one affected child (3%-4%) and a 10% risk for recurrence with two previously affected children (Kinsman and Johnston, 2011). The degree of neurologic dysfunction depends on where the sac protrudes through the vertebrae, the anatomic level of the defect, and the amount of nerve tissue involved. The majority of myelomeningoceles (75%) involve the lumbar or lumbosacral area (Fig. 49-6). Hydrocephalus is a frequently associated anomaly in 80% to 90% of the children. About 80% of patients with myelomeningocele develop a type II Chiari malformation (Kinsman and Johnston, 2011). There is some evidence that prolonged exposure of the MMC sac to amniotic fluid predisposes an infant to the development of hindbrain herniation and Chiari II malformation (Adzick, 2013). The diagnosis of SB is made on the basis of clinical manifestations (Box 49-5) and examination of the meningeal sac (see Fig. 49-6, A). Diagnostic measures used to evaluate the brain and spinal cord include MRI, ultrasonography, and CT. A neurologic evaluation will determine the extent of involvement of bowel and bladder function as well as lower extremity neuromuscular involvement. Flaccid paralysis of the lower extremities is a common finding with absent deep tendon reflexes. It is possible to determine the presence of some major open NTDs prenatally. Ultrasonographic scanning of the uterus and elevated maternal concentrations of α-fetoprotein (AFP, or MS-AFP), a fetal-specific γ-1-globulin, in amniotic fluid may indicate anencephaly or myelomeningocele. The optimum time for performing these diagnostic tests is between 16 and 18 weeks of gestation before AFP concentrations normally diminish and in sufficient time to permit a therapeutic abortion. It is recommended that such diagnostic procedures and genetic counseling be considered for all mothers who have borne an affected child, and testing is offered to all pregnant women (American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology [ACOG], 2007). Chorionic villus sampling is also a method for prenatal diagnosis of NTDs; however, it carries certain risks (skeletal limb depletion) and is not recommended before 10 weeks of gestation (Simpson, Richards, Otaño, et al., 2012). • The myelomeningocele and the problems associated with the defect—hydrocephalus, paralysis, orthopedic deformities (e.g., developmental dysplasia of the hip, clubfoot), and genitourinary abnormalities • Possible acquired problems that may or may not be associated, such as Chiari II malformation, meningitis, seizures, hypoxia, and hemorrhage • Other abnormalities, such as cardiac or gastrointestinal (GI) malformations Many hospitals have routine outpatient care by multidisciplinary teams to provide the complex follow-up care needed for children and families with myelodysplasia. Many authorities believe that early closure, within the first 24 to 72 hours, offers the most favorable outcome. Surgical closure within the first 24 hours is recommended if the sac is leaking CSF (Kinsman and Johnston, 2011). Associated problems are assessed and managed by appropriate surgical and supportive measures. Shunt procedures provide relief from imminent or progressive hydrocephalus (see Chapter 45). When diagnosed, ventriculitis, meningitis, urinary tract infection, and pneumonia are treated with vigorous antibiotic therapy and supportive measures. Surgical intervention for Chiari II malformation is indicated only when the child is symptomatic (i.e., high-pitched crowing cry, stridor, respiratory difficulties, oral-motor difficulties, upper extremity spasticity). Early surgical closure of the myelomeningocele sac through fetal surgery has been evaluated in relation to prevention of injury to the exposed spinal cord tissue and the improvement of neurologic and urologic outcomes in the affected child. The Management of Myelomeningocele Study, a clinical trial supported by the National Institutes of Health, found that prenatal surgery for myelomeningocele reduced the need for shunting (for hydrocephalus) as evaluated at 12 months and also decreased the incidence of hindbrain herniation. In addition, there was an improvement in mental and motor function scores at 30 months in the children who had prenatal surgery (compared with children who had postnatal surgery) (Adzick, Thom, Spong, et al., 2011). However, the surgery is not without risks to the fetus and mother, and premature delivery is common. Outcome data for urologic and bowel function, motor function, cognition, and spina bifida–associated outcomes are being gathered in the MOMS2 study, which is expected to end in late 2013 (Clinical Trials, 2013). Associated problems are assessed and managed by appropriate surgical and supportive measures. Shunt procedures provide relief from imminent or progressive hydrocephalus (see Chapter 45). Improved surgical techniques do not alter the major physical disability and deformity or chronic urinary tract and pulmonary infections that affect the quality of life for these children. Superimposed on these physical problems are the disorder’s effects on family life and finances and on school and hospital services. According to most orthopedists, musculoskeletal problems that will affect later locomotion should be evaluated early, and treatment, when indicated, should be instituted without delay. Neurologic assessment will determine the neurosegmental level of the lesion and enable recognition of spasticity and progressive paralysis, potential for deformity, and functional expectations. Orthopedic management includes prevention of joint contractures, correction of the existing deformity, prevention or minimization of the effects of motor and sensory deficits, prevention of skin breakdown, and acquisition of the best possible function of affected lower extremities. Common orthopedic problems requiring attention in SB include deformities of the knees, hips, feet, and spine; fractures and insensate skin further complicate orthopedic care. Other problems that may occur later include kyphosis and scoliosis (Lazzaretti and Pearson, 2010). Because children with this condition often have decreased sensitivity in their lower extremities, preventive skin care is important. A high percentage (60%) of children seen in a wound clinic for skin breakdown had myelomeningocele. The status of the neurologic deficit remains the most important factor in determining the child’s ultimate functional abilities. With technologic advances, a variety of lightweight orthoses, including braces, special “walking” devices, and custom-built wheelchairs, are available to provide mobility to children with spinal cord lesions (see also Chapter 36). Early in infancy, intervention with passive range-of-motion exercises, positioning, and stretching exercises may help decrease the incidence of muscle contractures. Corrective surgical procedures, when indicated, are best initiated at an early age so the child will not lag significantly behind age mates in developmental progress. When there is little hope for lower extremity functioning, surgery is seldom recommended unless it will improve sitting position in a wheelchair and function for ADLs and mobility.

Neuromuscular or Muscular Dysfunction

Congenital Neuromuscular or Muscular Disorders

Cerebral Palsy

Pathophysiology

Clinical Classification

Diagnostic Evaluation

Therapeutic Management

Prognosis.

Care Management

Support the Family.

Spina Bifida (Myelomeningocele)

Pathophysiology

Diagnostic Evaluation

Prenatal Detection.

Therapeutic Management

Postnatal Care.

Musculoskeletal Considerations.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Neuromuscular or Muscular Dysfunction

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access