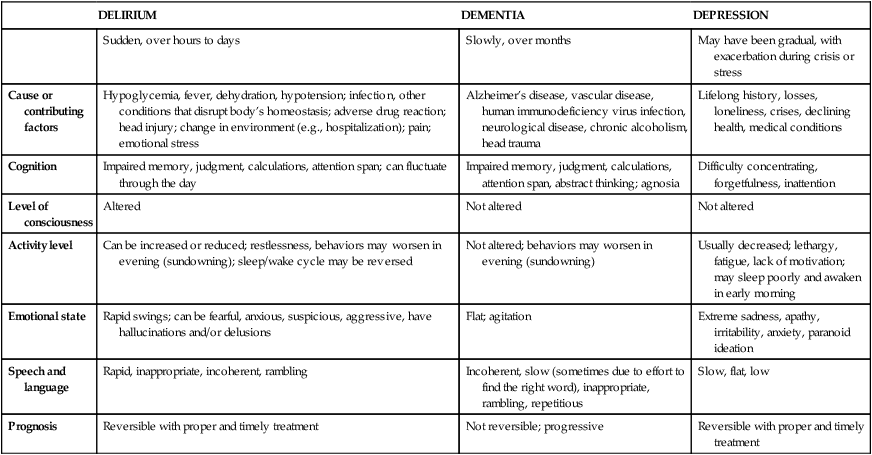

CHAPTER 23 1. Compare and contrast the clinical picture of delirium with that of dementia. 2. Discuss three critical needs of a person with delirium, stated in terms of nursing diagnoses. 3. Identify three outcomes for patients with delirium. 4. Summarize the essential nursing interventions for a patient with delirium. 5. Recognize the signs and symptoms occurring in the stages of Alzheimer’s disease. 6. Give an example of the following symptoms assessed during the progression of Alzheimer’s disease: (a) amnesia, (b) apraxia, (c) agnosia, and (d) aphasia. 7. Formulate three nursing diagnoses suitable for a patient with Alzheimer’s disease and define two outcomes for each. 8. Formulate a teaching plan for a caregiver of a patient with Alzheimer’s disease, including interventions for (a) communication, (b) health maintenance, and (c) safe environment. 9. Compose a list of appropriate referrals in the community—including a support group, hotline for information, and respite services—for persons with dementia and their caregivers. Visit the Evolve website for a pretest on the content in this chapter: http://evolve.elsevier.com/Varcarolis The three main neurocognitive syndromes are delirium, mild neurocognitive disorders, and major cognitive disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). All of these disorders are caused by physiological changes in brain function, structure, or chemistry, and all involve cognitive deficits that are a decline in the person’s previous functioning. The first syndrome is delirium, which is short-term and reversible; the remaining two syndromes, major and mild neurocognitive disorders, encompass what are commonly referred to as dementia,which is progressive and irreversible. Delirium is an acute cognitive disturbance and often-reversible condition that is common in hospitalized patients, especially older patients. It is characterized as a syndrome, that is, a constellation of symptoms, rather than a disease state per se. The cardinal symptoms of delirium are an alteration in level of consciousness, which manifests as altered awareness and an inability to direct, focus, sustain, and shift attention; an abrupt onset with clinical features that fluctuate (including periods of lucidity); and disorganized thinking and poor executive functioning. Other characteristics include disorientation (often to time and place and rarely to first person), anxiety, agitation (motor restlessness), poor memory (recall), delusional thinking, and hallucinations, usually visual. Patients experience delirium as a sudden change in reality with a sense that they are dreaming while awake. They experience dramatic scenes that engender strong feelings of fear, panic, and anger (Duppils & Wikblad, 2007). Delirium is considered a medical emergency that requires immediate attention to prevent irreversible and serious damage (Caplan et al., 2008). Delirium is associated with increased morbidity and mortality (Inouye et al., 2001) and can have lasting long-term consequences (Quinlan & Rudolph, 2011). While delirium is usually short term, there are long-term consequences that are currently better defined through large-scale epidemiological studies (Rudolph & Marcantonio, 2011). In patients with preexisting cognitive impairment (for example, dementia), there is an acceleration of cognitive decline. While there are reports of long-term cognitive impairment (in the absence of preexisting cognitive impairment) and functional decline following delirium, results of studies have been inconsistent. There is an association with depression post delirium, and evidence indicates that younger patients who have been delirious while hospitalized may develop posttraumatic stress disorder-like symptoms (Jones et al., 2001; Jones et al., 2007). Delirium is the most common complication of hospitalization in older patients (Rice et al., 2011). The reported incidence of delirium in hospitalized patients ranges from 3% to 56% (Michaud et al., 2007), from 11% to 42% in medically ill older patients (Cerejeira & Mukactova-Ludinska, 2011), and from 4% to 65% in postoperative patients, depending on the type of surgery (Rudolph & Marcantonio, 2011). The high degree of variability in the reported incidence of delirium is most likely due to its underrecognition by both nurses and doctors who work in acute-care settings/hospitals. Predisposing factors for delirium include age, lower education level, sensory impairment, decreased functional status, comorbid medical conditions, malnutrition, and depression (Flagg et al., 2010). Postoperative conditions, systemic disorders, withdrawal of drugs and substances such as alcohol and sedatives, toxicity secondary to drugs or other substances, and impaired respiratory functioning (Tasman & Mohr, 2011). While the key to offsetting the consequences of delirium is prompt recognition and investigations into possible causes, there is research evidence that the syndrome is poorly recognized and understood by both nurses and doctors (Rice et al., 2011; Flagg et al., 2010). Early recognition and diagnosis is challenging for clinicians due to lack of knowledge about cognitive impairment and its clinical assessment, failure to interpret the signs and symptoms, and nurses’ overreliance on disorientation as the only sign of cognitive impairment (Flagg et al., 2010). At present the best evidence for the prevention and management of delirium in hospitalized patients is having clinical protocols for minimizing the risk factors and for the early detection of delirium (Cerejeira & Mukactova-Ludinska, 2011). The best approach is collaboration between health care providers, with nurses being in the most likely position to first observe the signs and symptoms of delirium (Milisen et al., 2005). In addition, proactive consultation with geriatric specialists has been shown to reduce delirium in hospitalized patients (Siddiqi et al., 2007). Early recognition is the key to offsetting the potential consequences, as the condition if often reversible. While symptoms of delirium must be managed, the goal of treatment is to determine the underlying cause and rectify this when possible (Rudolph & Marcantonio, 2011). This means that clinicians who suspect delirium and note its symptoms should undertake a thorough examination, including mental and neurological status examinations as well as a physical examination. Blood tests should be undertaken along with a urinalysis. In addition, the patient’s medication regimen should be examined. A failure to quickly detect and treat delirium is associated with significant increase in morbidity and mortality (Rice et al., 2011). According to Wei and colleagues (2008), there are four cardinal features of delirium: 1. Acute onset and fluctuating course 2. Reduced ability to direct, focus, shift, and sustain attention Hallucinations are false sensory stimuli (refer to Chapter 12). Visual hallucinations are common in delirium, and tactile hallucinations may also be present. For example, individuals experiencing delirium may become terrified when they “see” giant spiders crawling over the bedclothes or “feel” bugs crawling on or under their bodies. Auditory hallucinations occur more often in other psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia. Medications should always be suspected as a potential cause of delirium (Sadock & Sadock, 2008). To recognize drug reactions or anticipate potential interactions before delirium actually occurs, it is important to assess all medications (prescription and over-the-counter) the patient is taking. • Patient will remain safe and free from injury while in the hospital. • During periods of lucidity, patient will be oriented to time, place, and person with the aid of nursing interventions, such as the provision of clocks, calendars, maps, and other types of orienting information. • Patient will remain free from falls and injury while confused, with the aid of nursing safety measures. • Preventing physical harm due to confusion, aggression, or electrolyte and fluid imbalance • Performing a comprehensive nursing assessment to aid in identifying the cause • Assisting with proper health management to eradicate the underlying cause The Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC) (Bulechek et al., 2013) can be used as a guide to develop interventions for a patient with delirium (Box 23-1). Medical management of delirium involves treating the underlying organic causes. If the underlying cause of delirium is not treated, permanent brain damage may ensue. Judicious use of antipsychotic or antianxiety agents may also be useful in controlling behavioral symptoms. Dementia is a broad term used to describe progressive deterioration of cognitive functioning and global impairment of intellect with no change in consciousness. It is not a specific disease per se, but rather a collection of symptoms that are due to an underlying brain disorder. These disorders are characterized by cognitive impairments that signal a decline from previous functioning. When mild, the impairments do not interfere with instrumental activities of daily living although the person may need to make extra efforts. While such impairments may be progressive, most people with a mild cognitive impairment will not progress to dementia (Mitchell & Shiri-Feshki, 2009). When progressive, these disorders interfere with daily functioning and independence. While often characterized by memory deficits, dementia affects other areas of cognitive functioning, for example, problem solving (executive functioning) and complex attention. Dementia is the general term used to describe a variety of progressive conditions that develop when brain cells die or no longer function; Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common type of dementia, accounting for 60% to 80% of all dementias (Alzheimer’s Association, 2012). It is a devastating disease that not only affects the person who has it but also places an enormous burden on the families and caregivers of those affected. Nurses practicing in most any setting will care for patients with AD and must be prepared to respond. It is important to distinguish between normal forgetfulness and the memory deficit of AD and other dementias. Severe memory loss is not a normal part of growing older. Slight forgetfulness is a common phenomenon of the aging process (age-associated memory loss) but not memory loss that interferes with one’s activities of daily living. Table 23-1 outlines memory changes in normal aging and memory changes seen in dementia. TABLE 23-1 MEMORY DEFICIT: NORMAL AGING VERSUS DEMENTIA From Alzheimer’s Association. (2013). 10 early signs and symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. Retrieved from http://www.alz.org/alzheimers_disease_10_signs_of_alzheimers.asp. There are several types of dementia. Dementia is associated with AD, frontotemporal lobar degeneration, Lewy bodies, vascular issues, traumatic brain injury, substances, HIV infection, Prion disease, Parkinson’s disease, and Huntington’s disease (APA, 2013). Regardless of the cause, dementia is classified as either a mild or a major neurocognitive disorder. Minor neurocognitive disorders are characterized by symptoms that place individuals in a zone between normal cognition and noticeably significant cognitive deterioration. The rationale for the introduction of a mild category is that identifying early-presenting symptoms may aid in earlier interventions at a stage when some disease-modifying therapies may be most neuroprotective (Sperling et al., 2011). Major neurocognitive disorders are characterized by substantial cognitive decline that results in curtailed independence and functioning among affected individuals. AD, the most common type of dementia, attacks indiscriminately, striking men and women, people of various ethnicities, rich and poor, and individuals with varying degrees of intelligence. Although the disease can occur at a younger age (early onset), most of those with the disease are 65 years of age or older (late onset). It is estimated that 5.4 million Americans have AD (Alzheimer’s Association, 2012). Globally, it is estimated that 24.3 million people have dementia, and the number of people will double every 20 years to 81.1 million by 2040 (Ferri et al., 2005). Although the cause of AD is unknown, most experts agree that, like other chronic and progressive conditions, it is a result of multiple factors that include genetics, lifestyle, and environmental. While many causes are hypothesized, the greatest risk factor is advanced age (Alzheimer’s Association, 2012; Lehne, 2013). In the brains of people with AD there are signs of neuronal degeneration that begins in the hippocampus, the part of the brain responsible for recent memory, and then spreads into the cerebral cortex, the part of the brain responsible for problem solving and higher-order cognitive functioning (Lehne, 2013). There are two processes that contribute to cell death. The first is the accumulation of the protein XXgw:math1XXbZZgw:math1ZZ-amyloid outside the neurons, which interferes with synapses; the second is an accumulation of the protein tau inside the neurons, which forms tangles that block the flow of nutrients. More research is needed into these mechanisms as some people who have these brain changes do not go on to develop AD (Alzheimer’s Association, 2012). There are three known genetic mutations that guarantee that a person will develop AD, although these account for less than 1% of all cases. These mutations lead to the devastating early-onset form of AD, which occurs before the age of 65 and as young as 30 years (Alzheimer’s Association, 2012). A susceptibility gene has been identified for late-onset AD as well. It is a gene that makes the protein apolipoprotein E, APOE 4, which helps carry cholesterol and is also implicated in cardiovascular disease (Alzheimer’s Association, 2012). Individuals who have or have had family members with AD are understandably concerned about their own risk for developing the disorder. For those who may carry the early-onset gene, genetic counseling, available through the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, is recommended. Commercial testing is available for one of the three genes that can confirm the disease or predict its onset, but this testing raises significant ethical concerns (Wright et al., 2008). APOE 4 testing is also available but has limited predictive value. The health of the brain is closely linked to overall heart health, and there is evidence that people with cardiovascular disease are at greater risk of AD. Likewise, lifestyle factors associated with cardiovascular disease, such as inactivity, high cholesterol, diabetes and obesity, are considered risk factors for AD (Alzheimer’s Association, 2012). Brain injury and trauma are associated with a greater risk of developing AD and other dementias. People who suffer repeated head trauma, such as boxers and football players, may be at greater risk. There is a suggestion that individuals who suffer brain injury and carry the gene APOE 4 are at greater risk (Alzheimer’s Association, 2012). Nurse: Good morning, Ms. Jones. How was your weekend? Patient: Wonderful. I discussed politics with the president, and he took me out to dinner. Patient: I spent the weekend with my daughter and her family. Symptoms observed in AD include the following: • Memory impairment: Initially the person has difficulty remembering recent events. Gradually, deterioration progresses to include both recent and remote memory. • Disturbances in executive functioning (planning, organizing, abstract thinking): The degeneration of neurons in the brain results in the wasting away of the brain’s working components. These cells contain memories, receive sights and sounds, cause hormones to secrete, produce emotions, and command muscles into motion. • Aphasia (loss of language ability): Initially the person has difficulty finding the correct word, then is reduced to a few words, and finally is reduced to babbling or mutism. • Apraxia (loss of purposeful movement in the absence of motor or sensory impairment): The person is unable to perform once-familiar and purposeful tasks. For example, in apraxia of dressing, the person is unable to put clothes on properly (may put arms in trousers or put a jacket on upside down). • Agnosia (loss of sensory ability to recognize objects): For example, a person may lose the ability to recognize familiar sounds (auditory agnosia), such as the ring of the telephone. Loss of this ability extends to the inability to recognize familiar objects (visual or tactile agnosia), such as a glass, magazine, pencil, or toothbrush. A wide range of problems may be mistaken for dementia or AD. Depression in the older adult is the disorder frequently confused with dementia. In fact, many persons diagnosed with Alzheimer’s dementia also meet the diagnostic criteria for a depressive disorder. In addition, dementia and depression or dementia and delirium can coexist. It is important that nurses and other health care professionals be able to assess some of the important differences among depression, dementia, and delirium. Table 23-2 outlines important differences among these three phenomena. TABLE 23-2 COMPARISON OF DELIRIUM, DEMENTIA, AND DEPRESSION When symptoms of dementia are present, a comprehensive assessment must be completed in order to rule out conditions that mimic dementia but are treatable. Making a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease includes ruling out all other pathophysiological conditions through the history and through physical and laboratory tests, many of which are identified in Box 23-2.

Neurocognitive disorders

Delirium

Clinical picture

Epidemiology

Comorbidity and etiology

Application of the nursing process

Assessment

Overall assessment

Cognitive and perceptual disturbances

Physical needs

Outcomes identification

Implementation

Dementia

Clinical picture

TYPICAL AGE-RELATED CHANGES

SIGNS OF ALZHEIMER’S

Making a bad decision once in a while

Poor judgment and decision making

Missing a monthly payment

Inability to manage a budget

Forgetting which day it is and remembering later

Losing track of the date or the season

Sometimes forgetting which word to use

Difficulty having a conversation

Losing things from time to time

Misplacing things and being unable to retrace steps to find them

Epidemiology

Etiology

Biological factors

Neuronal degeneration

Genetic

Risk factors in alzheimer”s disease

Cardiovascular disease

Head injury and traumatic brain injury

Application of the nursing process

Assessment

General assessment

Diagnostic tests

DELIRIUM

DEMENTIA

DEPRESSION

Sudden, over hours to days

Slowly, over months

May have been gradual, with exacerbation during crisis or stress

Cause or contributing factors

Hypoglycemia, fever, dehydration, hypotension; infection, other conditions that disrupt body’s homeostasis; adverse drug reaction; head injury; change in environment (e.g., hospitalization); pain; emotional stress

Alzheimer’s disease, vascular disease, human immunodeficiency virus infection, neurological disease, chronic alcoholism, head trauma

Lifelong history, losses, loneliness, crises, declining health, medical conditions

Cognition

Impaired memory, judgment, calculations, attention span; can fluctuate through the day

Impaired memory, judgment, calculations, attention span, abstract thinking; agnosia

Difficulty concentrating, forgetfulness, inattention

Level of consciousness

Altered

Not altered

Not altered

Activity level

Can be increased or reduced; restlessness, behaviors may worsen in evening (sundowning); sleep/wake cycle may be reversed

Not altered; behaviors may worsen in evening (sundowning)

Usually decreased; lethargy, fatigue, lack of motivation; may sleep poorly and awaken in early morning

Emotional state

Rapid swings; can be fearful, anxious, suspicious, aggressive, have hallucinations and/or delusions

Flat; agitation

Extreme sadness, apathy, irritability, anxiety, paranoid ideation

Speech and language

Rapid, inappropriate, incoherent, rambling

Incoherent, slow (sometimes due to effort to find the right word), inappropriate, rambling, repetitious

Slow, flat, low

Prognosis

Reversible with proper and timely treatment

Not reversible; progressive

Reversible with proper and timely treatment

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access