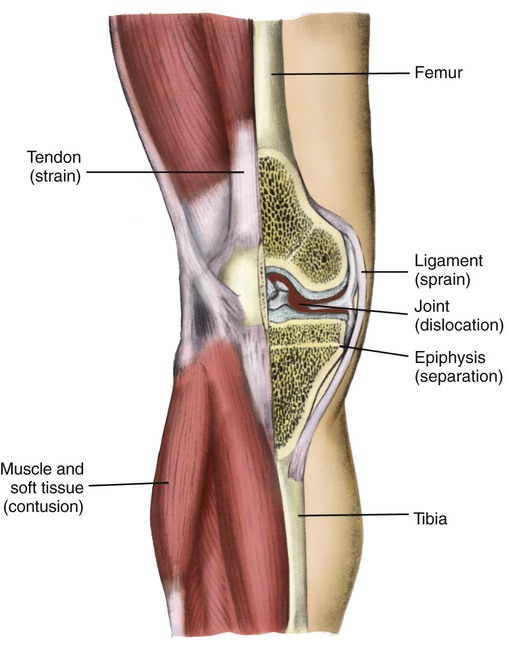

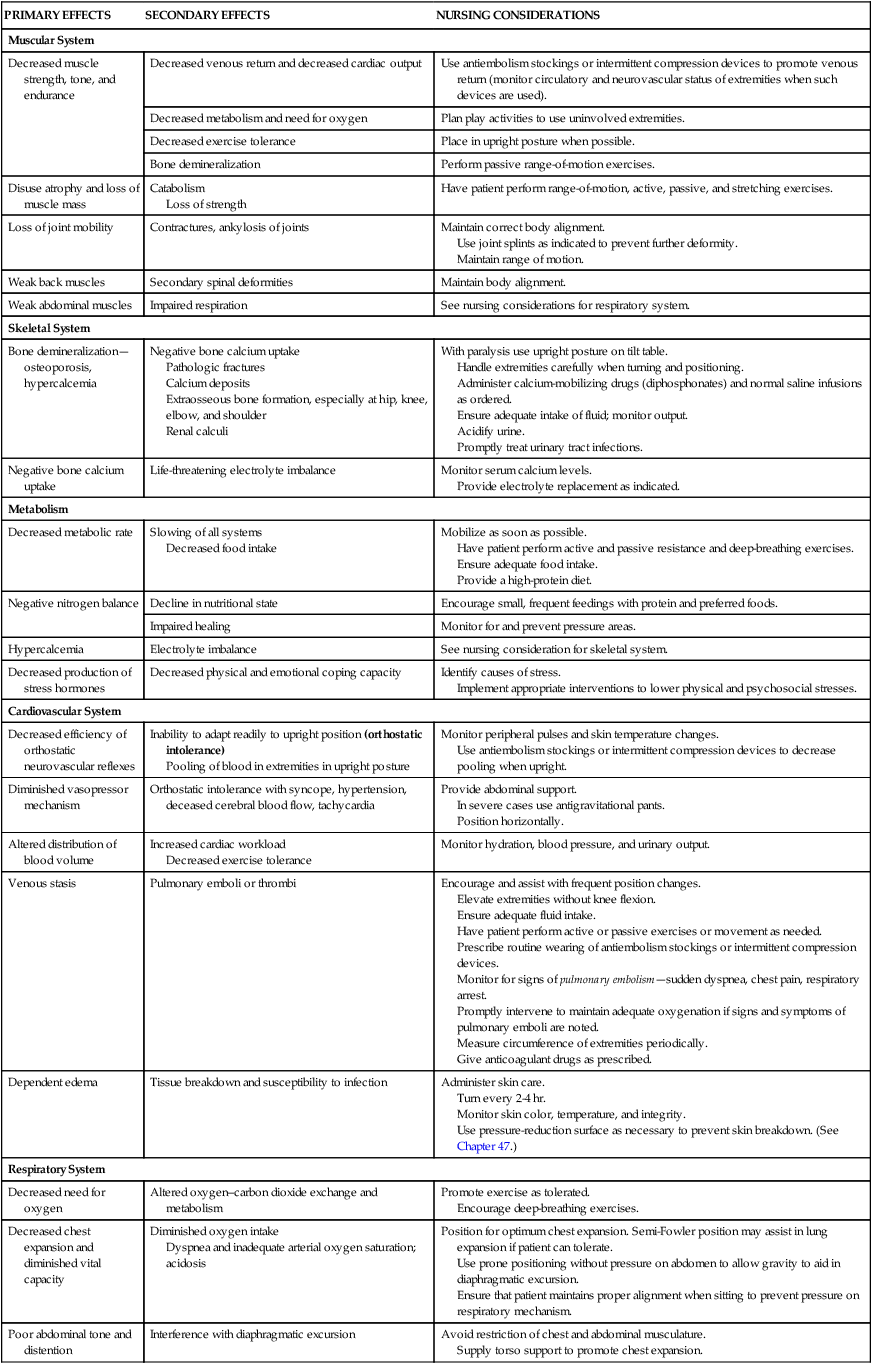

Chapter 48 On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Outline a care plan for a child immobilized with an injury or a debilitating condition. • Formulate a teaching plan for the parents of a child in a cast. • Explain the functions of the various types of traction. • Differentiate among the various congenital skeletal defects. • Design a teaching plan for the parents of a child with a congenital skeletal deformity. • Describe the therapies and nursing care of a child with scoliosis. • Outline a plan of care for a child with osteomyelitis. • Differentiate between osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma. • Describe the nursing care of a child with juvenile arthritis. • Demonstrate an understanding of the management of systemic lupus erythematosus. The major effects of immobilization are outlined briefly in Table 48-1 and are related directly or indirectly to decreased muscle activity, which produces numerous primary changes in the musculoskeletal system with secondary alterations in the cardiovascular, respiratory, metabolic, and renal systems. The musculoskeletal changes that occur during disuse are a result of alterations in gravity and stress on the muscles, joints, and bones. Muscle disuse leads to tissue breakdown and loss of muscle mass (atrophy). Muscle atrophy causes decreased strength and endurance, which may take weeks or months to restore. TABLE 48-1 SUMMARY OF PHYSICAL EFFECTS OF IMMOBILIZATION WITH NURSING INTERVENTIONS* *Individualize care according to child’s needs; interventions may vary in different institutions. The major musculoskeletal consequences of immobilization are as follows: • Significant decrease in muscle size, strength, and endurance • Bone demineralization leading to osteoporosis Circulatory stasis combined with hypercoagulability of the blood, which results from factors such as damage to the endothelium of blood vessels (Virchow triad), can lead to thrombus and embolus formation. Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) involves the formation of a thrombus in a deep vein such as the iliac and femoral veins and can cause significant morbidity if it remains undetected and untreated. The larger the portion of the body immobilized and the longer the immobilization, the greater the risks of consequences of immobility. The family’s needs often must be met by the services of a multidisciplinary team, and nurses play a key role in anticipating the services they will need and coordinating conferences to plan care. In preparation for discharge home visits are advisable, and home management is commonly planned weeks in advance of the actual discharge. Such planning includes special considerations for cultural, economic, physical, and psychologic needs. A child with a severe disability is very dependent, and caregivers need rest periods to revitalize themselves (respite). Individual and group counseling is beneficial for solving problems in advance and provides an emotional support system. Parent groups may also be helpful and often allow nonthreatening social contact. The families of children with permanent disabilities need long-term resources because some of the most difficult problems arise as they try to sustain high-quality care for many years (see Chapter 36). Children who require prolonged total immobility and are unable to move themselves in bed should be placed on a pressure-reduction mattress to prevent skin breakdown. Frequent position changes also help prevent dependent edema and stimulate circulation, respiratory function, gastrointestinal motility, and neurologic sensation. Children at greater risk for skin breakdown include those with prolonged immobilization; mechanical ventilation; orthotic and prosthetic devices, including wheelchairs; and casts. Additional risk factors include poor nutrition, friction (from bed linen with traction), and moist skin (from urine or perspiration). Nursing care of children at risk includes strategies for preventing skin breakdown when such conditions are present. The Braden Q Scale is a reliable, objective tool that may be used in the assessment for pressure ulcer development in children who are acutely ill or at risk for skin breakdown from neurologic conditions and immobilization (Noonan, Quigley, and Curley, 2011) (see also Maintaining Healthy Skin, Chapter 39). Whenever possible, transporting the child outside the confines of the room increases environmental stimuli and allows social contact with others. Specially designed wheelchairs for increased mobility and independence are available. While hospitalized, children benefit from same-age visitors, computers, books, interactive video games, and other items brought from their own room at home, all of which help them to function in a more normal way. They also benefit from frequent visitors, accessibility of clocks and calendars, and a program of diversional therapy to help them function more normally. A child life specialist should be consulted for recreational planning. An activity center or slanting tray can be helpful for the child with limited mobility to use for drawing, coloring, writing, and playing with small toys such as trucks and cars. Children are able to express frustration, displeasure, and anger through play activities (see Chapter 38), which are helpful in the child’s recovery. Hospitalized children should be allowed to wear their own clothes (street clothes, especially for preadolescent and adolescent girls) and resume school and preinjury activities. A parent or siblings should be allowed to stay overnight and room in with the hospitalized child to prevent the effects of family disruption caused by hospitalization. All efforts should be made to minimize this disruption. Although most of the suggestions discussed relate to hospital care, the same consultations (physical therapist, occupational therapist, child life specialist, speech therapist) and environment may also be considered in the home to help the child and family achieve independence and normalization. Injuries to the muscles, ligaments, and tendons are common in children (Fig. 48-1). In young children soft-tissue injury usually results from mishaps during play. In older children and adolescents, participation in sports is the more common cause. Long bones are held in approximation to one another at the joint by ligaments. A dislocation occurs when the force of stress on the ligament is so great as to displace the normal position of the opposing bone ends or the bone end from its socket. The predominant symptom is pain that increases with attempted passive or active movement of the extremity. In dislocations there may be an obvious deformity and inability to move the joint. Dislocation of the phalanges is the most common type seen in children, followed by elbow dislocation. One of the most common injuries in young children is subluxation of the annular ligament, also called pulled elbow or nursemaid elbow. With this injury the annular ligament slips proximally off the radial head into the joint between the radial head and ulna, causing immediate pain and limited supination (Carrigan, 2011). In the majority of cases the injury occurs in a child younger than 5 years who receives a sudden longitudinal pull or traction at the wrist while the arm is fully extended and the forearm pronated. It usually occurs when an adult or older sibling who is holding the child by the hand or wrist gives a sudden pull or jerk to prevent a fall or attempts to lift the child by pulling the wrist or when the child pulls away by dropping to the floor or ground. The child often cries, appears anxious, and refuses to use the affected limb; there is an absence of swelling. The practitioner manipulates the arm by applying firm finger pressure to the head of the radius, then supinates and flexes the forearm to return the ligament to its place. A click or clunk may be heard or felt, and functional use of the arm returns within minutes. However, the longer the subluxation is present, the longer it takes for the child to recover mobility after treatment. Usually no anesthetic is required, but a mild pain reliever such as acetaminophen may be given. In an older child severe elbow injury or dislocation should be carefully evaluated by a practitioner immediately; likewise a traumatic elbow injury in the younger child that is not a subluxation should be evaluated carefully. Simple dislocations should be reduced as soon as possible with the child under mild (procedural) sedation and often local anesthesia. Anesthetics such as IV ketamine (Ketalar), midazolam (Versed), IV propofol (Diprivan), or fentanyl (Sublimaze) can be used to produce partial or complete analgesia. Nitrous oxide in concentrations of 50% to 70% has been shown to be safe for relatively short periods (15 to 20 minutes) in children ages 1 year and above (Babl, Oakley, Seaman, et al., 2008; Zier and Liu, 2011) An unreduced dislocation is complicated by increased swelling, making reduction difficult and increasing the risk of neurovascular problems. Treatment depends on the severity of the injury. Torn ligaments, especially those in the knee, are usually treated by immobilization with a knee immobilizer or range-of-motion brace until the child is able to walk without a limp. Crutches are used for mobility to rest the affected extremity. Passive leg exercises, gradually increased to active ones, are begun as soon as sufficient healing has taken place. Parents and children are cautioned against using any form of liniment or other heat-producing preparation before examination. If the injury requires casting or splinting, the heat generated in the enclosed space can cause extreme discomfort and even tissue damage. In many cases torn knee ligaments are managed with arthroscopy and ligament repair or reconstruction as necessary, depending on the extent of the tear, the ligaments involved, and the child’s age. Surgical reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament may be performed in young athletes who wish to continue in active sports (Sarwark, 2010).

Musculoskeletal or Articular Dysfunction

The Immobilized Child

Physiologic Effects of Immobilization

PRIMARY EFFECTS

SECONDARY EFFECTS

NURSING CONSIDERATIONS

Muscular System

Decreased muscle strength, tone, and endurance

Decreased venous return and decreased cardiac output

Use antiembolism stockings or intermittent compression devices to promote venous return (monitor circulatory and neurovascular status of extremities when such devices are used).

Decreased metabolism and need for oxygen

Plan play activities to use uninvolved extremities.

Decreased exercise tolerance

Place in upright posture when possible.

Bone demineralization

Perform passive range-of-motion exercises.

Disuse atrophy and loss of muscle mass

Catabolism

Loss of strength

Have patient perform range-of-motion, active, passive, and stretching exercises.

Loss of joint mobility

Contractures, ankylosis of joints

Maintain correct body alignment.

Use joint splints as indicated to prevent further deformity.

Maintain range of motion.

Weak back muscles

Secondary spinal deformities

Maintain body alignment.

Weak abdominal muscles

Impaired respiration

See nursing considerations for respiratory system.

Skeletal System

Bone demineralization—osteoporosis, hypercalcemia

Negative bone calcium uptake

Pathologic fractures

Calcium deposits

Extraosseous bone formation, especially at hip, knee, elbow, and shoulder

Renal calculi

With paralysis use upright posture on tilt table.

Handle extremities carefully when turning and positioning.

Administer calcium-mobilizing drugs (diphosphonates) and normal saline infusions as ordered.

Ensure adequate intake of fluid; monitor output.

Acidify urine.

Promptly treat urinary tract infections.

Negative bone calcium uptake

Life-threatening electrolyte imbalance

Monitor serum calcium levels.

Provide electrolyte replacement as indicated.

Metabolism

Decreased metabolic rate

Slowing of all systems

Decreased food intake

Mobilize as soon as possible.

Have patient perform active and passive resistance and deep-breathing exercises.

Ensure adequate food intake.

Provide a high-protein diet.

Negative nitrogen balance

Decline in nutritional state

Encourage small, frequent feedings with protein and preferred foods.

Impaired healing

Monitor for and prevent pressure areas.

Hypercalcemia

Electrolyte imbalance

See nursing consideration for skeletal system.

Decreased production of stress hormones

Decreased physical and emotional coping capacity

Identify causes of stress.

Implement appropriate interventions to lower physical and psychosocial stresses.

Cardiovascular System

Decreased efficiency of orthostatic neurovascular reflexes

Inability to adapt readily to upright position (orthostatic intolerance)

Pooling of blood in extremities in upright posture

Monitor peripheral pulses and skin temperature changes.

Use antiembolism stockings or intermittent compression devices to decrease pooling when upright.

Diminished vasopressor mechanism

Orthostatic intolerance with syncope, hypertension, deceased cerebral blood flow, tachycardia

Provide abdominal support.

In severe cases use antigravitational pants.

Position horizontally.

Altered distribution of blood volume

Increased cardiac workload

Decreased exercise tolerance

Monitor hydration, blood pressure, and urinary output.

Venous stasis

Pulmonary emboli or thrombi

Encourage and assist with frequent position changes.

Elevate extremities without knee flexion.

Ensure adequate fluid intake.

Have patient perform active or passive exercises or movement as needed.

Prescribe routine wearing of antiembolism stockings or intermittent compression devices.

Monitor for signs of pulmonary embolism—sudden dyspnea, chest pain, respiratory arrest.

Promptly intervene to maintain adequate oxygenation if signs and symptoms of pulmonary emboli are noted.

Measure circumference of extremities periodically.

Give anticoagulant drugs as prescribed.

Dependent edema

Tissue breakdown and susceptibility to infection

Administer skin care.

Turn every 2-4 hr.

Monitor skin color, temperature, and integrity.

Use pressure-reduction surface as necessary to prevent skin breakdown. (See Chapter 47.)

Respiratory System

Decreased need for oxygen

Altered oxygen–carbon dioxide exchange and metabolism

Promote exercise as tolerated.

Encourage deep-breathing exercises.

Decreased chest expansion and diminished vital capacity

Diminished oxygen intake

Dyspnea and inadequate arterial oxygen saturation; acidosis

Position for optimum chest expansion. Semi-Fowler position may assist in lung expansion if patient can tolerate.

Use prone positioning without pressure on abdomen to allow gravity to aid in diaphragmatic excursion.

Ensure that patient maintains proper alignment when sitting to prevent pressure on respiratory mechanism.

Poor abdominal tone and distention

Interference with diaphragmatic excursion

Avoid restriction of chest and abdominal musculature.

Supply torso support to promote chest expansion.

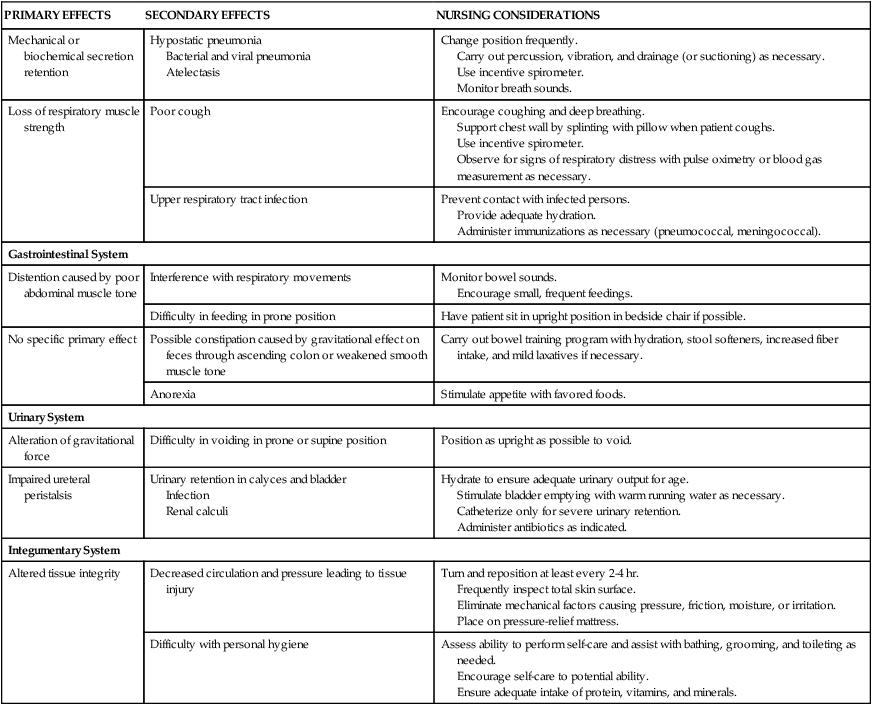

Mechanical or biochemical secretion retention

Hypostatic pneumonia

Bacterial and viral pneumonia

Atelectasis

Change position frequently.

Carry out percussion, vibration, and drainage (or suctioning) as necessary.

Use incentive spirometer.

Monitor breath sounds.

Loss of respiratory muscle strength

Poor cough

Encourage coughing and deep breathing.

Support chest wall by splinting with pillow when patient coughs.

Use incentive spirometer.

Observe for signs of respiratory distress with pulse oximetry or blood gas measurement as necessary.

Upper respiratory tract infection

Prevent contact with infected persons.

Provide adequate hydration.

Administer immunizations as necessary (pneumococcal, meningococcal).

Gastrointestinal System

Distention caused by poor abdominal muscle tone

Interference with respiratory movements

Monitor bowel sounds.

Encourage small, frequent feedings.

Difficulty in feeding in prone position

Have patient sit in upright position in bedside chair if possible.

No specific primary effect

Possible constipation caused by gravitational effect on feces through ascending colon or weakened smooth muscle tone

Carry out bowel training program with hydration, stool softeners, increased fiber intake, and mild laxatives if necessary.

Anorexia

Stimulate appetite with favored foods.

Urinary System

Alteration of gravitational force

Difficulty in voiding in prone or supine position

Position as upright as possible to void.

Impaired ureteral peristalsis

Urinary retention in calyces and bladder

Infection

Renal calculi

Hydrate to ensure adequate urinary output for age.

Stimulate bladder emptying with warm running water as necessary.

Catheterize only for severe urinary retention.

Administer antibiotics as indicated.

Integumentary System

Altered tissue integrity

Decreased circulation and pressure leading to tissue injury

Turn and reposition at least every 2-4 hr.

Frequently inspect total skin surface.

Eliminate mechanical factors causing pressure, friction, moisture, or irritation.

Place on pressure-relief mattress.

Difficulty with personal hygiene

Assess ability to perform self-care and assist with bathing, grooming, and toileting as needed.

Encourage self-care to potential ability.

Ensure adequate intake of protein, vitamins, and minerals.

Effect on Families

Care Management

Traumatic Injury

Soft-Tissue Injury

Dislocations

Therapeutic Management

R—Rest

I—Ice

I—Ice

C—Compression

C—Compression

E—Elevation

E—Elevation

S—Support

Fractures

Types of Fractures

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Musculoskeletal or Articular Dysfunction

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access