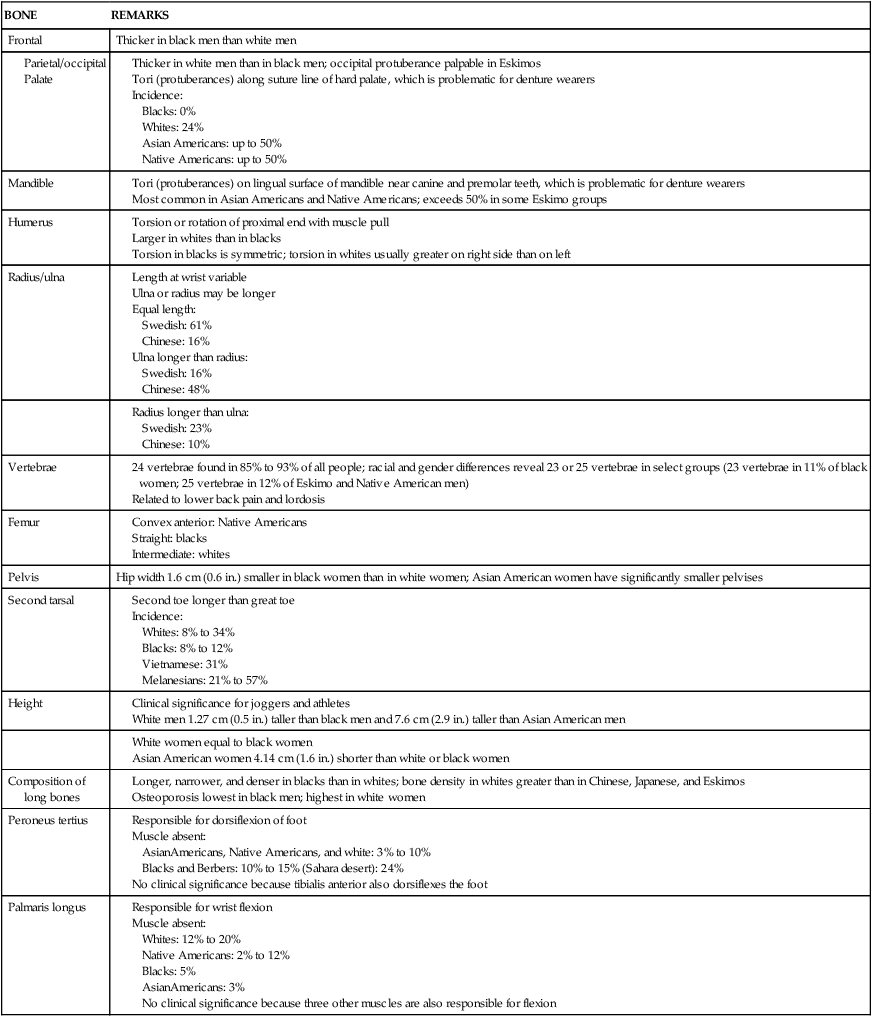

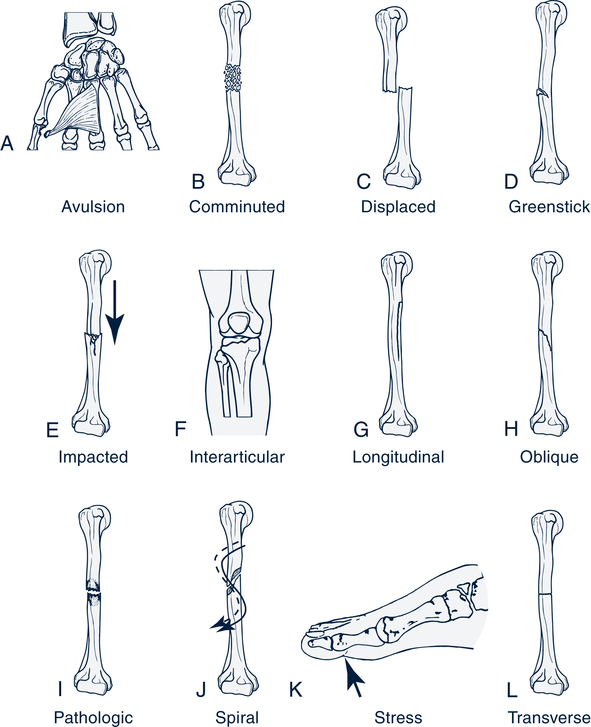

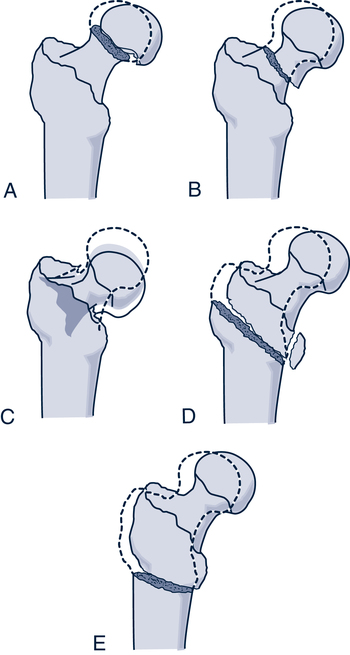

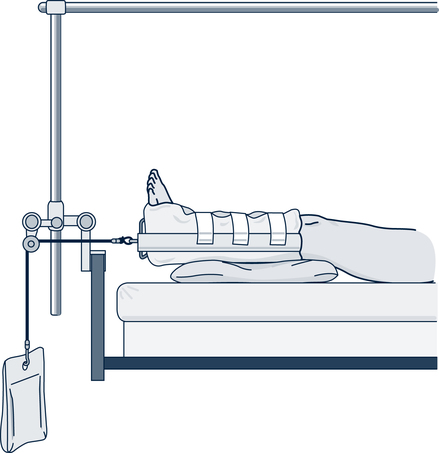

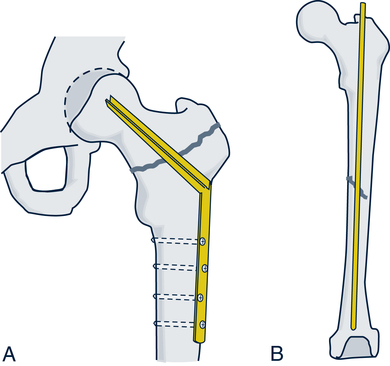

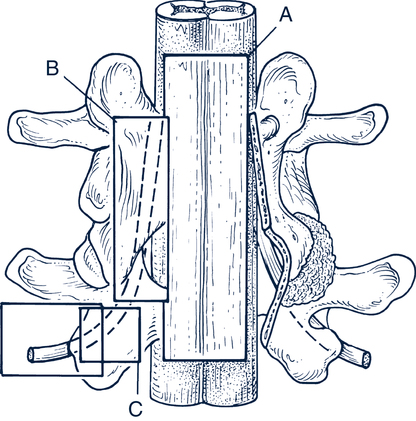

Ramesh C. Upadhyaya, RN, CRRN, MSN, MBA On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Describe the normal structure and function of the musculoskeletal system. 2. Discuss the age-related changes in the musculoskeletal system. 3. Discuss the nursing management of clients with fractures of the hip, wrist, clavicle, and vertebra. 4. Distinguish differences among osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, and polymyalgia rheumatica. 5. Identify the nursing interventions associated with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, and polymyalgia rheumatica. 6. Discuss the pathophysiology, treatment, and nursing management of osteoporosis. 7. Describe the indications for amputation in older adults and the nursing management of these clients. 8. Discuss the causes and management of common foot problems in older adults. Musculoskeletal problems are common among older adults. The Administration on Aging (2008) found that 40% of older adults living in the community are given diagnoses of arthritis, and 17% report having other chronic problems of the musculoskeletal system. Complaints in the musculoskeletal system are common because normal aging predisposes people to the development of diseases such as osteoarthritis and osteoporosis. Diseases of the musculoskeletal system are usually not fatal but can lead to chronic pain and disability. Chronic conditions of the musculoskeletal system may contribute to impaired function and disability in older adults in the areas of self-care and mobility. They may suffer impairments in the ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs), such as bathing, dressing, and eating, and impairments in the ability to perform instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), such as managing finances, preparing food, managing transportation, and keeping house. Functional impairment of ADLs and IADLs can be devastating to older adults who desire to maintain independence. When dependence occurs, it can result in loss of self-esteem, the perception of decreased quality of life, and depression (see Cultural Awareness Box) (Netz, Wu, Becker, & Tenenbaum, 2005). incurred during the fall (Gray-Miceli, Strumpf, Johnson,et al, 2006; American Geriatrics Society, 2001; Stevens, Corso, Finkelstein, & Miller, 2006). It has been estimated that residents have a 50% to 75% incidence of falls in nursing homes. The mean incidence is 1.5 falls per bed per year. Falls are the most common cause of accidental death in older adults. When falls result in injury and hospitalization, the risk of iatrogenic illness and immobility can lead to a downward trajectory, which can ultimately result in death. Falls may also cause a cycle of disuse. This pattern of disuse usually occurs after the individual has experienced repeated falls. The fall experience causes a fear of falling. To avoid falls, the individual decreases mobility; with decreased mobility, muscle strength decreases, joints become stiff, and pain develops, resulting in disability, loss of independence, and frailty (Gray-Miceli et al, 2006). Current research has documented that some of the diseases and decline in the musculoskeletal system can be decreased or prevented through the use of regular programs of active exercise and resistive muscle strengthening (Stevens et al, 2006). Fractures are common problems for older adults that often result in some loss of functional ability. A fracture is a break or disruption in the continuity of the bone. Fractures may occur because of trauma to a bone or joint, or they may be the result of pathologic processes such as osteoporosis or neoplasms. When bones are subjected to more stress than can be withstood, a fracture occurs. Stresses on bones may be from major trauma such as automobile accidents or falls. Falls are the most common cause of fractures in older adults. The most frequently occurring fractures among older adults are hip fractures, fractures of the proximal femur, Colles’ (wrist) fractures, vertebral fractures, and clavicular fractures. Fractures are classified as open or closed by the location and type of fracture (Fig. 27–1). Hip fractures are the most disabling type of fracture for older adults. They usually are caused by falls and result in direct trauma to the hip. Approximately 24% of clients with hip fractures die within 1 year after the injury (Wolinsky, Fitzgerald, & Stump, 1997). The complications of hip fractures are generally related to immobility. They include pneumonia, sepsis from urinary tract infections, and pressure ulcers. With the growing number of older adults, especially those older than 75, it is expected that the incidence of hip fractures will increase. Hip fractures are classified by their locations. Intracapsular fractures, or subcapital fractures, occur within the hip capsule. Extracapsular fractures occur outside or below the capsule and are referred to as intertrochanteric and subtrochanteric locations (Fig. 27–2). After the fall or injury that results in the fractured hip, the client has an affected extremity that is usually externally rotated and shortened. Tenderness and severe pain at the fracture site may be present. Immediately after the injury, the joint should be immobilized. Buck’s or Russell’s traction (Fig. 27–3) is used until the client is stabilized. After the client is stabilized, surgical repair, the preferred treatment, is performed. The type of surgical repair depends on the location and type of fracture and can include internal fixation with pins, plates, and screws, or prosthetic replacement of the femoral head (Fig. 27–4). Nursing diagnoses for a client with a hip fracture include • Pain related to discomfort from the muscle and bone trauma • Impaired physical mobility related to immobilization of the fracture and the healing process • Risk for impaired skin integrity related to the immobilization required for healing • Risk for infection related to possible impaired wound healing, compromised nutrition, and effects of immobility • Self-care deficit (bathing and hygiene, grooming, dressing, and toileting) related to discomfort and impaired mobility • Impaired home maintenance management related to decreased independence and recovery period needed for fracture healing 1. The client will report minimum discomfort and an adequate level of pain control. 2. The client will remain free from postoperative complications, such as altered skin integrity and wound infection. 3. The client will adhere to the prescribed physical therapy regimen to regain function of the affected joint. 4. The client will be able to participate in physical and occupational therapies. 5. The client will be able to safely demonstrate use of assistive devices for mobility and ADLs. 6. The client will be able to return to the preinjury level of independence with appropriate support and assistive devices. These problems can be prevented if lower initial doses of narcotics than those used with younger adults are used. The individual’s response to the pain medication and the pain are closely monitored. If low doses are tolerated, the dose may be carefully increased. Keeping the affected extremity in alignment during turning also decreases pain. This is done with the use of pillows between the knees or an abduction splint. After the devastating events of hip fracture and surgery, comprehensive multidisciplinary rehabilitation focuses on returning the client to the prior level of function and preventing disability. Specific areas of treatment are gait and transfer training, muscle strengthening through active assistive exercises, teaching the use of adaptive techniques for dressing, and teaching the correct use of assistive devices. Walkers and canes will be used by the client (Fig. 27–5), and the nurse must ensure that the client uses a safe technique with either device (see Client/Family Teaching Box: Correct Use of Walkers). bathing. Synthetic casts are immersed in water only with physician approval and should be dried thoroughly afterward. A hair dryer set at a low temperature may be used for this purpose. Casts are generally used to immobilize fractures for 6 to 8 weeks. A variety of assistive devices may be used for clients with lower extremity casts (Fig. 27–6). The nurse prepares the client for self-care and prevention of complications during this treatment period. The most common symptom is a gradual onset of aching joint pain. The pain occurs with activity and is relieved with rest. Stiffness after periods of inactivity that resolves with activity is also seen in osteoarthritis. Crepitus, a grating sound and sensation, may be heard and felt with range of motion in affected joints. Affected joints also have a decreased range of motion. The degeneration of the joint structure may result in muscle spasms, gait changes, and disuse of the joint. Bony enlargements, called Heberden’s nodes (Fig. 27–7), may be seen on the distal interphalangeals. antiinflammatory agent. Other medical treatment options for more severe pain may include directly injecting the painful joint with steroids. This can be done two or three times yearly for chronic pain. More recent developments in arthritis treatment include the injection of hyaluronic acid into a painful knee joint that has not responded to more conservative measures. The nurse should educate the client about these conservative measures for treating the symptoms of arthritis. Information regarding correct dosing of oral medications, contraindications, side effects, and adverse effects should be provided. Major complications after joint replacement surgery may include thromboembolism (deep venous thrombosis [DVT]), joint or wound infection, blood loss, nerve injury, joint dislocation, and surgical pain. The risk of DVT is highest between the first and second week after surgery. The use of critical pathways or care paths in most institutions has resulted in shortened hospital stays, fewer incidents of complications, and improved outcomes (Branson & Goldstein, 2003; Theis, 1998). independence in daily activities. A short stay in a rehabilitation facility may follow the acute hospital stay. However, many clients are able to quickly return to their own home with continued home therapy services. Symptomatic osteoarthritic changes of the spine leading to functional limitation and pain in older adults are becoming more common. Lumbar spinal stenosis is one of the most frequently encountered, clinically important degenerative spinal disorders in the aging population (Spivak, 1998). Degenerative spinal stenosis is a bony overgrowth of the facet joints of the vertebrae, which leads to narrowing of the spinal canal and possible compression of the nerve roots. Although spinal stenosis can occur at any level of the spine, it is most frequently seen in the lumbar region at levels L3 and L4 (Fig. 27–8). Degeneration of the vertebral joints and disks of the spine, along with nerve compression, leads to progressive back pain and possible weakness of lower extremities. Clients with spinal stenosis may develop claudication-like symptoms of burning and numbness in their lower extremities. 1. The client will report a minimum or tolerable level of pain. 2. The client will demonstrate improved mobility and tolerance of activity. 3. The client will be able to incorporate a plan for lifestyle modifications that includes activity and rest. 4. The client will demonstrate safe use of assistive devices and make necessary environmental changes to promote safety.

Musculoskeletal Function

Age-Related Changes in Structure and Function

Common Problems and Conditions of the Musculoskeletal System

Hip Fracture

Nursing Management

![]() Assessment

Assessment

![]() Diagnosis

Diagnosis

![]() Planning and Expected Outcomes

Planning and Expected Outcomes

![]() Intervention

Intervention

Clavicular Fracture

Casts and Cast Care

Osteoarthritis

Nursing Management

![]() Assessment

Assessment

![]() Intervention

Intervention

Spinal Stenosis

Nursing Management

![]() Assessment

Assessment

![]() Planning and Expected Outcomes

Planning and Expected Outcomes

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access