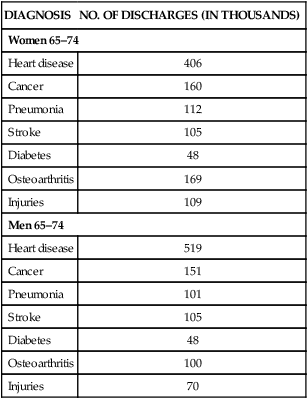

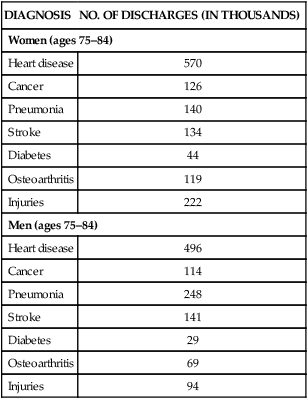

Pamala D. Larsen, PhD, CRRN, FNGNA On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Define chronic illness and its relationship with rehabilitation. 2. Identify potential goals for an older adult with chronic illness. 3. Plan interventions that support an older adult’s adaptation to a chronic illness or disability. 4. Describe the nurse’s role in assisting older adults in managing chronic conditions. 5. Identify opportunities for change in the health care system to improve care for older adults with chronic illness and disability. It is important to differentiate between the terms chronic disease and chronic illness. Often these terms are used interchangeably by both health care providers and the general public. Disease refers to a condition viewed from a pathophysiologic model, such as an alteration in structure and function; it is a physical dysfunction of the body. Illness is what the individual (and family) are experiencing, that is, how the disease is perceived, lived with, and responded to by individuals and families (Larsen, 2009a). As health care providers, we can often modify the disease process or assist the client in obtaining optimal health; however, often times it is the illness experience that we can most affect. Just as the terms chronic disease and illness are complex, defining them is as well. An early national group, the Commission on Chronic Illness (1957) defined chronic illness as The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2009a) define chronic disease as Chronic illness is the irreversible presence, accumulation, or latency of disease states or impairments that involve the total human environment for supportive care and self-care, maintenance of function, and prevention of further disability (Curtin & Lubkin, 1995). More than 133 million adults in the United States have one or more chronic conditions, which is 1 of every 2 adults (CDC, 2009a). Chronic conditions continue to be the primary causes of death in individuals 65 or older. Note the number of chronic conditions in Table 17–1. As one might expect, the medical costs of individuals with chronic conditions accounts for more than 75% of our nation’s medical care costs each year (CDC, 2008). TABLE 17–1 PERCENTAGE OF DEATHS FROM LEADING CAUSES AMONG PERSONS AGES 65 AND OVER: UNITED STATES, 2005 From National Center for Health Statistics: Health, United States, chartbook on trends in the health of Americans, Hyattsville, Md, 2008, The Center. Although chronic disease and disability can occur at any age, the bulk of these conditions occurs in adults 65 years or older. Julie Gerberding, former director of the CDC, stated that “the aging of the U.S. population is one of the major public health challenges we face in the 21st century” (CDC & Merck Company, 2007). By 2030 there will be nearly 70 million older Americans, representing 20% of the total population as compared with 13.2% predicted for 2010 (Administration on Aging, 2009). As we age, the chances of having a chronic condition increase. The State of Aging and Health in America (CDC & Merck Company, 2007) reports that 80% of older Americans have at least one chronic health condition. Similarly, Medicare data document that 83% of all its beneficiaries have at least one chronic condition (Anderson, 2005). Comorbidities are particularly common: approximately 50% of older adults having at least two or more chronic conditions (CDC & Merck Company, 2007). With this increasing number of individuals with a chronic condition, the health care system has to do a better job of caring for them. Nursing care, in particular, needs to focus on increasing functional ability, preventing complications, promoting the highest quality of life, and, when the end stage of life occurs, providing comfort and dignity in dying. A key role for the nurse caring for an older adult with a chronic condition is to help the client achieve optimal physical and psychosocial health. The most frequently occurring conditions in older adults in 2004 to 2005 (most current data available) include hypertension, diagnosed arthritis, heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and sinusitis (Administration on Aging, 2008). Regarding hypertension, National Hospital Discharge Survey data state that 65% of men and 80% of women 75 years or older either had high blood pressure or were taking antihypertensive medications in 2003-2006 (National Center for Health Statistics, 2008). Individuals with chronic conditions typically have repeated hospitalizations to treat exacerbations of their illness. For both men and women ages 65 to 74, the most common reasons for hospitalization are heart disease, cancer, pneumonia, and stroke (Table 17–2). As men and women reach 75 or older, these diseases continue to predominate (Table 17–3). Hospitalizations resulting from injuries, particularly in women (e.g., hip fractures), increase significantly, as does heart disease in this age category. Given these statistics, one can see that elderly women have significantly more hospitalizations than do men of the same age. TABLE 17–2 From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Hospital Discharge Survey: Health, United States, 2008. TABLE 17–3 HOSPITAL DISCHARGES AND BY DIAGNOSIS (AGES 75–84): 2006 From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Hospital Discharge Survey: Health, United States, 2008. The Agency, Atlanta, Ga The diagnosis of a chronic disease and subsequent management of that disease bring unique experiences and meanings of the process to both the client and family (Larsen, 2009b). Just as each individual and his or her disease process is unique, so too are the meanings and experiences of that disease to the individual and his or her family. However, the educational background of most health care professionals is one that fits with the medical model and does not consider the different illness perceptions and illness behaviors of individuals. We have been taught that patients have diseases and the degree of their pathology dictates their treatment. Health care has even developed algorithms that tell us how and what care to provide. Nonetheless, having a chronic illness is not a black and white, quantifiable concept. There are many shades of gray. Kleinmann, a longtime author on illness behavior and its meaning, becomes concerned that researchers have “reduced sickness to something divorced from meaning in order to avoid the heard and still unanswered technical questions concerning how to actually go about measuring meaning and objectivizing and quantifying its effect on health status and illness behavior” (Kleinmann, 1985). Concepts of health and illness are deeply rooted in culture, race, and ethnicity and influence an individual’s (and family’s) illness perceptions and health and illness behavior (Larsen & Hardin, 2009). Ethnic minorities do not necessarily subscribe to the values or tenets associated with this country’s medical system. Additionally, each culture is not homogeneous, and there are variations and subcultures within each. According to the 2000 U.S. Census, approximately 30% of the population is racially and ethnically diverse. Projections are that by 2100 this percentage will increase to 40%, and non-Hispanic whites will make up only 60% of the U.S. population (CDC, 2009b). With these increasing numbers of ethnically and culturally diverse older adults, health care providers need to be better attuned to their needs. There are a number of nursing frameworks that can assist health care providers in providing culturally competent care. The website of the Transcultural Nursing Society (www.tcns.org) provides information about six different theories and models. Models include those by Margaret Andrews and Joyceen Boyle, Josepha Campinha-Bacote, Joyce Giger and Ruth Davidhizar, Madeline Leininger, Larry Purnell, and Rachel Spector. Advancements in health care have increased interest in the quality of life (QOL) of persons with chronic illnesses. There are multiple definitions of quality of life, but most include physical, psychologic, and social components; disease and treatment-related symptoms; and spirituality. There is no consensus, however, on the definition. The following definition, although somewhat older, fits well with older adults. QOL is an individual’s perceptions of well-being that stem from satisfaction or dissatisfaction with dimensions of life that are important to the individual (Ferrans & Powers, 1985). This definition is particularly applicable to chronic illness. The complexity of health and function in chronic illness, particularly if one believes that health can be present within illness, suggests that neither “good” health nor functional abilities are necessary for quality of life. QOL is determined by the individual, not the health care provider. To further confuse the issue, most researchers draw a distinction between QOL and health-related quality of life (HRQOL). Most suggest that HRQOL is a subset of QOL. Brown, Renwick, and Nagler (1996) believe that HRQOL should be used in a narrow sense within the medical–nursing environment by those who are interested in the outcomes and quality of changes resulting from medical and nursing interventions. Patrick and Erickson (1993) conceptualize HRQOL in terms of opportunity, health perceptions, functional status, impairment, and death and duration of life. In the past, compliance has been the term used for all patient behaviors consistent with health care recommendations (Holroyd & Creer, 1986). However, the term adherence has now replaced compliance because adherence is the term used on the global stage of health care delivery (Berg, Evangelista, Carruthers, & Dunbar-Jacob, 2009). There are a number of factors that influence nonadherence. Factors include (1) individual characteristics, (2) psychologic factors, (3) social support, (4) prior health behaviors, (5) somatic factors, (6) regimen characteristics, (7) economic and sociocultural factors, and (8) client–provider interactions (Berg et al, 2009). The World Health Organization (WHO) suggests adopting the use of the five As in an effort to assist patients with the self-management aspects of their chronic disease, of which treatment adherence is just one part (2003). The 5 As include assess, advise, agree, assist, and arrange. Although these key aspects seem straightforward and easy to follow for health care providers, data suggest that there is only 50% adherence to treatment regimens for individuals with chronic illness (Dunbar-Jacob et al, 2000; WHO, 2003). There are mixed data in studies that examine age and adherence behaviors. Park and Skurnik (2004) suggest that there are a variety of factors that may interfere with the ability of the older adult to adhere to a treatment plan. However, in general, developmental issues, such as age, have not been well addressed in the adherence literature (Dunbar-Jacob et al, 2000). Berg et al (2009) suggest that although the 5 As is a good framework for health care providers to use, it is also important to (1) advise the patient of the importance of the treatment plan, (2) establish agreement with the treatment plan, and (3) arrange adequate follow-up. goals, or were these goals not mutually established but generated by the health care provider? The assessment should include identification of strengths such as self-motivation. Adaptation infers that there is an event or something unusual or different that is perceived as a threat or stressor to the individual that merits a reaction, a change, or a behavior by an individual (Stanton & Revenson, 2007). Other authors have seen adaptation as good quality of life, well-being, vitality, positive affect, life satisfaction, and global self-esteem (Sharpe & Curran, 2006). Adaptation is complex and multidimensional and is a holistic concept. Consensus exists regarding the centrality of an individual’s appraisal of their adjustment: it is their adjustment and their perception, not the health care professional’s (Stanton, Collins, & Sworowski, 2001). The prevention of medical crises and their management if they occur Carrying out the medical regimen Prevention of, or living with, social isolation Adjustment to change in the disease Attempts to normalize interactions and lifestyle Confronting attendant psychologic, marital, and familial problems (Strauss et al, 1984) Corbin and Strauss (1992) developed the trajectory framework to assist nurses in (1) gaining insight into the chronic illness experience of the client, (2) integrating existing literature about chronicity into their practice, and (3) providing direction for building nursing models that guide practice, teaching, research, and policy making. A trajectory is defined as the course of an illness over time, plus the actions that clients, families, and health care providers use to manage that course (Corbin, 1998). The illness trajectory is set in motion by the pathology of the client, but the actions taken by the health care providers, patient, and family can modify the course. Even if two older adults have the same chronic condition, the illness trajectory of each individual is different and takes into account the uniqueness of the individual (Jablonski, 2004). This model from Thorne and Paterson (1998) resulted from analyzing 292 qualitative studies on chronic physical illness that were published between 1980 to 1996. Of these, 158 studies became part of a metastudy in which client roles in chronic illness were described. The model depicts chronic illness as an ongoing, continually shifting process in which individuals experience a complex dialectic between the world and themselves (Paterson, 2001). The model considers both the “illness” and the “wellness” of the individual. The illness-in-the foreground perspective focuses on the sickness, loss, and burden of the chronic illness. With wellness-in-the-foreground, the self is the source of identify and not the disease. Neither the illness perspective or the wellness perspective is right or wrong but merely reflects the individual’s unique needs, health status, and focus at the time (Paterson, 2001).

Chronic Illness and Rehabilitation

Chronicity

CAUSE OF DEATH

NUMBER

PERCENT

All causes

1,788,189

100

Heart disease

530,926

Cancer

388,322

Cerebrovascular disease

123,881

Chronic lower respiratory disease

112,716

Alzheimer’s disease

70,858

Influenza and pneumonia

55,453

Diabetes

55,222

Prevalence of Chronic Illness

DIAGNOSIS

NO. OF DISCHARGES (IN THOUSANDS)

Women 65–74

Heart disease

406

Cancer

160

Pneumonia

112

Stroke

105

Diabetes

48

Osteoarthritis

169

Injuries

109

Men 65–74

Heart disease

519

Cancer

151

Pneumonia

101

Stroke

105

Diabetes

48

Osteoarthritis

100

Injuries

70

DIAGNOSIS

NO. OF DISCHARGES (IN THOUSANDS)

Women (ages 75–84)

Heart disease

570

Cancer

126

Pneumonia

140

Stroke

134

Diabetes

44

Osteoarthritis

119

Injuries

222

Men (ages 75–84)

Heart disease

496

Cancer

114

Pneumonia

248

Stroke

141

Diabetes

29

Osteoarthritis

69

Injuries

94

The Illness Experience

Cultural Competency

Quality of Life and Health-Related Quality of Life

Adherence in Chronic Illness

Psychosocial Needs of Older Adults with Chronic Illness

Adaptation

Chronic Illness and Quality of Life

Trajectory Framework

Shifting Perspectives Model of Chronic Illness

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Chronic Illness and Rehabilitation

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access