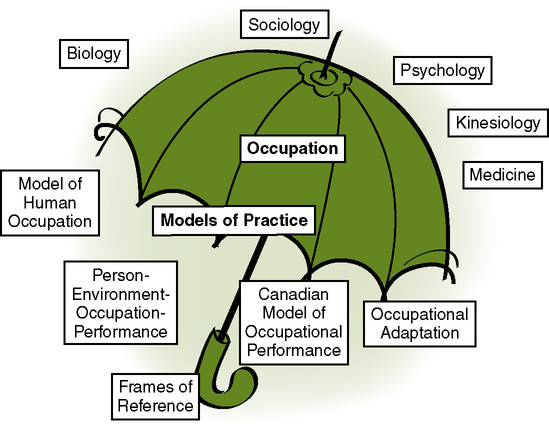

After reading this chapter, the reader will be able to do the following: • Define theory, model of practice (MOP), and frame of reference (FOR) • Discuss the importance of using a model of practice and frame of reference • Understand how research supports practice • Identify the components of a frame of reference • Summarize selected occupational therapy (OT) models of practice • Identify the principles guiding selected frames of reference A model of practice helps organize one’s thinking, where-as a frame of reference is a tool to guide one’s intervention.13,15 A frame of reference tells you what to do and how to evaluate and intervene with clients. Furthermore, frames of reference have research to support the principles guiding evaluation and intervention. Thus, using a frame of reference to guide one’s practice is essential to evidence-based practice. Evidence-based practice refers to choosing intervention techniques based upon the best possible research. This chapter will outline selected occupational therapy models of practice and frames of reference and describe how they are applied in practice. A theory is a set of ideas that helps explain things. Research is used to support or refute theories. Occupational therapy borrows theories from other disciplines such as psychology, medicine, nursing, and social work. Theory is the analysis of a set of facts in their relation to one another.14 There are two major structural components to theory: concepts and principles.24,25 Concepts are ideas that represent something in the mind of the individual. These range from simple concrete ideas to complex, abstract ideas. Concepts are expressed through the use of symbols and language. Children develop categories for different concepts. For example, a child learns that clothing is a category that can be divided into shoes, pants, dresses, and shirts, among others. Principles explain the relationship between two or more concepts.24 For instance, once the concept of color is learned, such as blue and yellow, a child learns the principle that mixing these two colors produces green. Theory is defined as “a set of interrelated assumptions, concepts, and definitions that presents a systematic view of phenomena by specifying relationships among variables, with the purpose of explaining and predicting the phenomena.”19 Theories range in scope and complexity along a continuum. Theories may be broad in scope and attempt to cover many aspects of a discipline, or they may have a narrow focus and concern only a small portion of the field.24 Figure 14-1 provides an illustration of how these concepts fit together. Parham states, “Theory is a key element in problem setting and in problem solving. It is a tool that enables the practitioner to ‘name it and frame it.’ Both language and logic are needed to identify a problem (name it) and to plan a means for altering the situation (frame it). Theory provides these by giving us words or concepts for naming what we observe and by spelling out logical relationships between concepts.”16 Theory allows the OT practitioner to structure and organize his or her intervention. Theory also serves to (1) validate and guide practice, (2) justify reimbursement, (3) clarify specialization issues, (4) enhance the growth of the profession and the professionalism of its members, and (5) educate competent practitioners.24 A model of practice takes the philosophical base of the profession and organizes the concepts for practice. As such, occupational therapy models of practice help OT practi- tioners organize their thinking around occupation,13 which is the central unifying feature of the occupational therapy profession. A model of practice provides practitioners with terms to describe practice, an overall view of the profession, tools for evaluation, and a guide for intervention.8,13,15 The Model of Human Occupation (MOHO)9 is the best-researched model of practice in occupational therapy. Kielhofner and colleagues have published extensively on all aspects of this model, and thus this model provides well-supported evidence to support its use in practice. The Model of Human Occupation views occupational performance in terms of volition, habituation, performance, and environment. Volition refers to the person’s motivation, interests, values, and belief in skill. Habituation refers to one’s daily patterns of behaviors, one’s roles (the rules and expectations of those positions), and one’s everyday routine. Performance refers to the motor, cognitive, and emotional aspects required to act upon the environment.9 Environment refers to the physical, social, and societal surroundings in which the person is involved. Each system is divided into components with many well-researched instruments to operationalize the terms for practice.9 Working with the assessment tools designed to operationalize the concepts of the model helps practitioners understand the concepts more fully for practice. The Canadian Model of Occupational Performance (CMOP)10,22 has also generated a wealth of research to support its design. The core of this model is spirituality, which is defined broadly as anything that motivates or inspires a person.10,22 Person, environment (which includes institutions), and occupations are the other parts of the model. This model emphasizes client-centered care,10,22 which refers to understanding the client’s desires and wishes for intervention and outcome. Getting to know the client is crucial to this model. The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure11 is a semistructured interview based on this model and provides practitioners with a tool to organize their thoughts. The Person-Environment-Occupation-Performance (PEOP) model6 developed by Christiansen and Baum provides definitions for each term and describes the interactive nature of the human being. This model provides generic, broad terms for each area (e.g., person, environment, occupation, performance). Person includes the physical, social, and psychological aspects of the individual. Environment includes the physical and social supports, and those things that interfere with the individual’s performance. Occupation refers to the everyday things people do and in which they find meaning. Performance refers to the actions of occupations.6 Occupational Adaptation, articulated by Schkade and Schultz, proposes that OT practitioners examine how they may change the person, environment, or task so the client may engage in occupations. In this model, occupation is viewed as the primary means for the individual to achieve adaptation. Individual adaptation is seen as both a state of being and a process that can be examined at a given time, over a specified time period, or over a lifetime.20 This model focuses on the person, the occupational environment, and the interaction. It supports compensatory techniques if necessary. The following case studies provide an overview of the use of the different models of practice. Volition: Raven enjoys family events, singing, and cooking. Raven lives close to her family and sees her mother, three children, and many other family members daily. Furthermore, the family attends church services on Sunday and then gathers at Raven’s for a potluck supper. She is active in the church choir. Habituation: Raven works 5 days a week from 8 am to 5 pm in a local grocery store, where she is the assistant manager. She attends her grandchildren’s school events and periodically helps her daughters with child care and transportation. Raven attends church Wednesday evenings and Sundays. Performance: Prior to her aneurysm, Raven was able to complete all occupations without difficulty. Currently, she is unable to use her right side, slurs her speech, has difficulty maintaining a conversation, and becomes easily confused. Raven is unable to remain active for over 20 minutes, showing obvious signs of fatigue. Environment: Raven lives in a small apartment building in the city with her husband. She has been married for 20 years. They live on the third floor. The building has elevators, but Raven is afraid to use them. Raven’s family members live close by and frequently visit her. She holds many family gatherings at her house.

Models of Practice and Frames of Reference

Understanding Theory

Why Is It Important to Know About and Use Theory in Occupational Therapy Practice?

Model of Practice

Case Application

Model of Human Occupation

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Models of Practice and Frames of Reference

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access