Joyce Wilkinson, Neil Johnson, and Peter Wimpenny

- Review some key terms related to models of implementation

- Be introduced to a typology of models of implementation based on work of Nutley et al. (2007)

- Through this typology, be able to discuss the focus of a variety of extant models of implementation and their contribution to impact of evidence on practice

- Conclude on the use of the typology, the fit of models and the nature of future use in practice.

Introduction

This chapter will focus on developing an understanding of the utility and purpose of implementation models, which are described in more detail in Book 1 of this series (Rycroft-Malone & Bucknall, in press). A model typology will be used to assist this understanding drawn from empirical work on research use by Nutley et al. (2007). Such a typology enables us to classify implementation models and begin to focus on the different kinds of impacts that may be identified as a result of their application. Published examples are discussed in illustrating the differing foci of implementation models and the impacts identified from their use.

This chapter concludes by summarizing and highlighting the main aspects of the types of models and the impacts that these might inform, and reflects on the implications for their selection and use in practice.

However, firstly it is useful to describe some of the key terms that will be used throughout the chapter and for which there may be a myriad of interpretations.

Models

Many terms are used to describe what we have included in this chapter as models and we have sought to be inclusive, rather than exclude on the grounds of title. Instead, we have included anything which had as its aim a means of guiding, explicating, exploring, or representing in diagrammatic format, the evidence or research into practice process. These have variously been presented or described as models, strategies, approaches, diagrams, and frameworks and include those which are conceptual, theoretical, and empirically based. We have called them models for the purposes of this chapter.

Evidence-based practice

For ease of use, we will use the term “evidence” as an all-encompassing one, to include research, routine monitoring of data, experience, and expert opinion, all the while trying to focus on the process and impacts, rather than get drawn into wider debates about the nature of evidence. That said we also recognize that the nature of evidence and practitioners’ views of that, does, in itself, have an impact on the ways in which they engage with the evidence-into-practice process.

Likewise, the term “evidence-based” practice (EBP) leaves scope for varying interpretations, with the terms “evidence-informed” becoming more prominent as a means of reflecting the numerous ways in which evidence has the potential to influence practice, beyond being an obvious “base” on which practice changes or develops. Indeed, the different ways in which evidence can impact on practitioners is explored in more detail, later in this chapter, but cannot always be traced to an evidence-base or attributed to specific types or pieces of evidence. However, once again, rather than get sidetracked on semantic debates, we will use the term that is most familiar that of EBP.

Implementation and utilization

We view implementation as a process, not an event, through which evidence, practitioners and the work environment (and this could include patients also) are prepared to carry out some change in practice. We view this as a change management process that also involves evaluation and readjustment to allow for ongoing use of evidence which may not always be explicit or observable.

Impact

Dictionary definitions of impact suggest force and change, often hinting at some magnitude as we would associate with the impact of, for example, two cars colliding. However, we believe that impact from the use of evidence can be viewed as “difference”—the difference that using evidence has made for patients, practitioners, and local and national health-care organizations. These may be of some magnitude and of some reach or influence, but others may be much more subtle and not readily identified, even by practitioners themselves. Seeing impact as difference embraces a spectrum of impacts and therefore allows us the greatest potential to identify and highlight the numerous ways in which evidence can make a difference in practice. From this standpoint the models and impacts that we explore in this chapter can be seen to demonstrate or have the potential to demonstrate a broad range of measurable and less easily measurable impacts.

A model typology

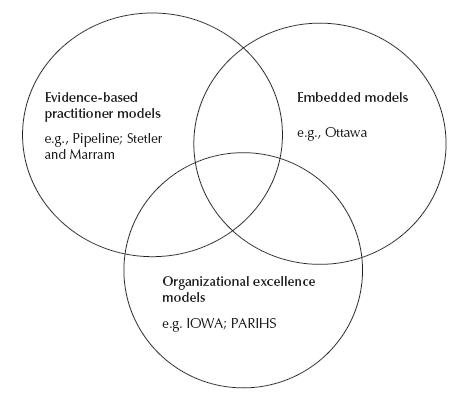

The model typology (Figure 3.1) has been adapted from empirical work, which focused originally on the ways in which evidence was used in social care (Walter et al. 2004) and wider empirical and conceptual work relating to research use across the public sector, including health care, through the Research Unit for Research Utilization at the University of St Andrews. The typology enables us to identify some main features of any model within three broad types.

Figure 3.1 Model typology.

A typology can be helpful in seeking to illuminate different models and their impact in the world of EBP as well as providing a more discerning analysis of the elements potentially enabling impacts to occur.

There are challenges in doing this. The boundaries where the three model types overlap create some blurring and it may be that there are wider areas of overlap than those shown. Another challenge is the lack of detail for some models which make the classification into a particular type difficult. For example, the IOWA model (Titler et al. 2001) instructs institute change in practice but does not provide detail as to how this should or could take place and as a result, it is more difficult, for example, to determine where it should sit. One further limitation of this typology is that despite the overall aim of models being to focus on guiding, testing, tracing or assisting the implementation of evidence into practice, detailed examination is not undertaken and if it is, there is no consensus on what should be examined. This makes any comparison difficult. An additional confounding factor is the lack of detail provided in published examples in relation to outcomes as they often focus much more on process. That said there is recognition that process impacts are still of importance and may be of equal significance in improving patient outcomes and in our understanding of the relationships between the factors contributing to the implementation of evidence-into-practice.

The features of each of the three model types are described below in Boxes 3.1–3.3.

These three different model types with their different approaches and foci will, we contend, determine different types of approaches to evidence use and therefore impacts for practitioners, practice, patients, and health-care organizations could also be different. Each of the model types will now be examined in more detail with illustrations from papers where a specific model has been used.

Evidence-based practitioner models

This model type reflects some of the earlier thinking in the evidence utilization field, in which the focus was predominantly on the ways in which individual practitioners could and should access evidence, appraise it, and if relevant, then use it in their practice.

- It is the role and responsibility of the individual practitioner to keep abreast of evidence and ensure that it is used to inform or act as a basis for day-to-day practice.

- This process is a linear one, which involves the practitioner accessing, appraising, and applying evidence to practice.

- Practitioners have high levels of professional autonomy to change practice to reflect evidence.

- Professional education, development, and training are important in enabling practitioners to use evidence in practice.

- Evidence use is achieved by a process of embedding evidence into the systems and processes of care provision, such as policies, standards, guidelines, protocols, procedures, and tools.

- Responsibility for ensuring evidence use lies with policy makers, guideline developers, and service delivery managers.

- The use of evidence is both a linear and an instrumental process: evidence is directly translated into practice change.

- Funding, performance management, and regulatory regimes are used to encourage the use of evidence-based guidance and tools.

- The key to successful evidence use rests with health-care organizations: their leadership, management, and organization.

- Evidence use is supported by developing an organizational culture that is “evidence-minded.”

- There is local adaptation of evidence and ongoing learning within organizations in an attempt to use local data as evidence for improvement of care.

- Partnerships with local universities and other intermediary organizations are fostered to facilitate both the creation and use of evidence for practice.

Despite the problems that began to emerge with this approach, for example, those identified by Hunt in her seminal paper of 1981, (such as practitioners’ lack of autonomy to change practice and lack of practitioner skills to read and appraise research) this is still a model that is widely considered to be the dominant means of getting evidence into practice although literature suggests that there may be an emergent sum of evidence to counter such a view (Rycroft-Malone et al. 2004). Rogers (1983) argued that in many instances individual adoption of new innovations (or in this case evidence) cannot occur unless organizational adoption occurs first. However, more recently Wilkinson (2008) has shown that nurse managers still believe that the full responsibility for EBP lies with individual staff and although some barriers to this are recognized, such as varying individual skills and ability, these are not considered to be such that nurses’ responsibilities for evidence use by this approach are negated.

The dominant aspect of this model type is the evidence content and the process of appraising and applying it to practice. For example, Heneghan et al. (2007) use the Pipeline model (Glasziou 2005; Glasziou & Haynes 2005) to consider the use of hypertension guidelines in a family doctor practice. The acceptability of the evidence to practitioners (and patients) is paramount, but ultimately adherence to the evidence is the “step” that is viewed as having the most impact in practice. It is a linear approach to evidence use that assumes that practitioners will have the knowledge, authority, and autonomy to make evidence-informed changes to their own practice.

This model reflects the understanding that the experiential knowledge of practitioners will be used to consider evidence and then make decisions about its appropriateness and subsequent use in practice. In the same way, the views of patients may also be taken into account, but there are difficulties relating to the precedence given to any particular aspect of this process and the primacy of some evidence (such as research) over other types (such as patient choice) and how these can be given equal footing. Thompson et al. (2001) have shown that nurses value the experience and opinion of others over published research and this was also borne out in other work (Wilkinson 2008). These highlight the difficulties of trying to use practitioner models in assessing impact when the types of evidence favored by practitioners can vary significantly and the decision-making processes that surround the choice of evidence and the accompanying processes that see it implemented or used in practice are so difficult to understand or articulate.

The evidence-based practitioner models also assume or reflect a belief that practitioners have, by dint of their professional status or specific job role, a level of autonomy over practice that will allow them to use evidence after they have accessed and appraised it. Heneghan et al. (2007) report on the changes to hypertension management by family doctors. Glaszious’ Pipeline model (2005) may be more applicable to doctors who are possessed of greater levels of autonomy over practice than other professional groups (Dopson & Fitzgerald 2005). The Pipeline model (Glasziou 2005) as illustrated in Heneghan and colleague’s (2007) paper, ends with adherence to evidence, but impacts or outcomes beyond this are not made explicit. Despite this, other impacts might be recognized at different stages of the model which may be considered to move the model to a more organizational type (Wimpenny et al. 2008) or from models that have the individual practitioner as the main focus.

The Stetler–Marram (1976) model also illustrates some of the difficulty in employing a practitioner-based model. The use of the Stetler model by McGuire (1990) highlights the lack of research appraisal skills in staff suggesting that implementation may be about more than just autonomy but also about knowledge and understanding of research and evidence in a variety of formats. However, subsequent use of the model for implementation may have been enhanced by the earlier experience and an increase in appraisal skills. Other models, such as the Ottawa Model of Research Utilization (Graham & Logan 2004), do identify the evidence itself as a factor in implementation but the model is focused more distinctively on the broader organizational structures and processes that may limit or assist the evidence into practice. While this may highlight issues of autonomy, reports of use do not identify this as a significant factor (Ellis et al. 2007; Graham & Logan 2004; Hogan & Logan 2004; Logan et al. 1999) suggesting the focus is not on the individual practitioner.

The above highlight the limitations of this model type, that is evidence use is viewed as a largely linear and uncomplicated process, which fails to take account of the numerous “barriers.” Studies undertaken now over two decades and in many countries and practice settings (e.g., Bryar et al. 2003; Dunn et al. 1998; Nilsson Kajermo et al. 1998; Oranta et al. 2002; Parahoo, 2000; Parahoo & McCaughan 2001; Restas 2000) show consistently that many practitioners do not believe that they have the necessary autonomy, authority, and skills to make changes to practice. This is not to say that some practitioners do not manage to make changes to practice that reflect evidence, but they are not the majority and they often work in roles that “give” them greater clarity and explicit autonomy than most practitioners.

If we try to consider the types of impacts that this model type might facilitate, the issues of access to evidence, skills to appraise and apply to practice, and the ability to take account of different sources of evidence and the need for explicit autonomy to be able to make changes to practice, several points begin to emerge. There are a number of factors that may inhibit any potential impact, such as individual practitioners’ skills and abilities, as well as organizational factors, such as local communication and the limits of authority and autonomy to make changes to practice, for either groups of practitioners or individuals. While this may limit the direct instrumental use of evidence in practice, the impact of these models may be seen in other ways (Box 3.4), which may, in time (although this is speculation or hope, rather than any certainty at this point) generally lead to greater use of evidence in practice.

Beyond those practitioners who have or are able to develop the skills that are necessary prerequisites, the impacts are likely to be negligible as the hurdles or barriers are just too great for individual practitioners to overcome. Even where they do have the autonomy (such as medical practitioners) there is often an underlying concern that evidence for the effectiveness of EBP is lacking (Miles et al. 2003) and a review of initiatives in social care (Walter et al. 2004) also suggest that individual skills and autonomy for evidence use are not the whole story in identifying impacts from evidence use in practice. Overall organizational encouragement or professional direction (such as that from the UK Nursing and Midwifery Council) to use evidence in practice, in the way suggested by this model type, does not clearly translate into use of evidence that can be readily identified or traced. The impact on patients from these models is likely to be very difficult indeed to attribute to the models without wider organizational structures and cultures that favor, enable, and support evidence use. Furthermore, this model type does not reflect the sources of knowledge for practice favored by nurses (Thompson et al. 2001; Wilkinson 2008) and any attempts to identify and trace evidence use processes would need to take account of the potential of the multiple sources of evidence available to practitioners and the ways in which these might be synthesized to inform practice. Many of these aspects of evidence-into-practice process, although known of, are as yet poorly understood.

- Increased knowledge and skills of individual practitioners for accessing, appraising, understanding, and using evidence to answer specific clinical problems.

- Increased awareness of different types of evidence and their applicability or appropriateness to practice for individuals (conceptual rather than instrumental use).

- Increased confidence in considering the need to change practice to better reflect evidence which may lead to changes to job role, such as a promoted post or involvement in evidence use projects at local or national level. These impacts could be considered as professional development for individuals.

- Impacts on wider teams, units or organization are likely to be limited, but will depend to a greater or lesser extent on the sphere of influence of the individual(s) involved.

- Increased networking or collaborations linked to evidence use may develop (Walter et al. 2005) and links to or development of continuing professional development or continuing education initiatives may take place as the result of these models having an impact for individuals, but also beyond the individual practitioner.

The potential impacts seen in Box 3.4 are offered as examples and are not viewed as an exhaustive list of every impact that might occur through the use of this model type. There are some impacts that may be conspicuous by their absence, such as those relating to improved patient outcomes, greater patient satisfaction or major changes to the ways in which care is provided. That is not to say that these types of impacts could not occur, but that it is less likely, and these types of impacts may be more readily identified through the use of other models. The potential of this model type also relies on the ability of practitioners to “unlearn” (Rushmer & Davies, 2004) routines and practices, as well as their ability to discover and use new evidence and ways of working. The use of practitioner-only-focused models might well be considered the dominant mode of evidence into practice for professionals, but their use, and therefore impact, is more likely to be haphazard and opportunistic and thus their potential impacts difficult to identify and measure.

Embedded evidence models

The embedded model type focuses on an approach to getting evidence used in practice without (necessarily) clearly identifying it as evidence. Those using evidence rarely engage directly with it and it is presented for use in practice in the form of guidelines, policies, procedures, protocols, or standards for care. Its provenance may not be known to the end user. There is an implicit understanding that these evidence products will be linked in with the tacit knowledge of practitioners, and will “make sense” to them.

The links in the embedded models are not initially between evidence and practitioners, but between evidence networks, policy makers, national agencies (such as the Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network, The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence or NHS Quality Improvement Scotland) and to organizational networks within health care that serve as intermediaries between these and practitioners. The responsibility for changing practice, or incorporating evidence, lies beyond health-care organizations and individual practitioners. Their respective roles are to communicate the evidence through internal networks and to facilitate their use and ensure adherence to the evidence content. Once again, it is largely a linear process, often from the top down, with the main focus on achieving instrumental use, with less focus on practitioner autonomy or authority to change practice. In fact, in contrast to the evidence-based practitioner models, this may actually be a barrier to the use of embedded models (Nutley et al. 2007; Walter et al. 2004). Use of these evidence products in practice may be demanded by the nature of the product (e.g., a policy would “have to” be adhered to) or controlled by the availability of specific equipment or resources (Wilkinson, 2008). It may also relate to the topic or subject area (Wimpenny & van Zelm 2007). In addition, the use of these products may be monitored and reported on in a routine manner through national schemes. Failure to adhere might be identified at local level through critical incident review or reporting, although the impact of not using an evidence-based product that should have been in use is acknowledged as being a somewhat negative example.

These models often involve different levels within organizations rather than focusing on ward level, since embedding of evidence also requires engagement at meso and macro levels, particularly important for effective dissemination as a necessary pre-condition for implementation processes. If the incorporation of evidence into products such as local guidelines or protocols for care takes place through organizational structures, such as shared governance arrangements, this will still require wider levels of engagement than that of individual wards/units or practitioners to be effective. The Ottawa Model of Research Use (OMRU) provides examples of attempts to embed evidence. The earliest of these reports is Logan et al. (1999) where pressure ulcer guidelines are implemented in a range of clinical settings. It is interesting to note that the “turmoil” of restructuring within the organization was an identified barrier to implementation and highlights the likelihood that there will never be ideal organizational conditions for implementation. While embedded evidence model types will seek to take account of contextual barriers and facilitators these will always be present. Graham and Logan (2004) in a later paper describe the use of the OMRU to introduce a skin-care program in five different organizational units, again reflecting a more strategic level approach to embedding evidence for practice across a health-care organization. Although Graham and Logan (2004) report “significant outcomes” from this approach, these are not stated or explicated in the paper.

In a different environment, Ellis et al. (2007) report on the use of the Ottawa model to guide the application of pain measurement tools for children. Again this is at unit level rather than focusing on individual practitioners and illustrates the use of OMRU as predominantly an embedding model type. However, Elllis et al. (2007) do report on the outcomes of use of pain scales (increased use, rather than widespread adoption), but the extent to which this leads to better outcomes or beneficial impact on patients is implicit, rather than clearly stated. Could the model have been used more effectively to assist in embedding evidence, through the use of a pain chart, into practice? If adherence was less than optimal or expected, why might this have been so and was this related to the choice or use of the model?

The impact of embedded evidence might be identified through local audits or the development of local protocols arising from national policies or directives, such as those used for the audit of water quality for dialysis patients, the use of nurse-led thrombolysis protocols or the supply of pressure-relieving mattresses (Wilkinson, 2008). These examples had each developed from national initiatives or directives, the latter, arising from the directive to rationalize the use of resources in one Scottish Health Board as a means of saving money but not compromising on care provision. The adoption of a local tool to assess pressure risk (but based on wider evidence) was underpinned by a Health Board wide protocol that determined the need for hiring-in expensive pressure-relieving mattresses and if appropriate, ensuring that these would be used for the minimum of time and returned promptly to minimize costs. However, none of these examples appeared to be guided or underpinned by the use of an explicit model such as OMRU, which has evaluation of patient, practitioner and health-care system outcomes as an integral part of the model.

These latter examples show that embedding evidence has the potential to demonstrate impact not only at the patient level, but also at meso and macro levels within health-care organizations. However, the example provided relating to the use of pressure mattresses may highlight the potential conflicts between “the evidence” and the patient’s choice. The patient may well prefer to spend longer on the supremely comfortable hired in mattress; however, “the evidence” may show that once the patient is able to turn themselves in bed or mobilize independently, there is no clinical benefit (i.e., improved outcome) to continuing to use the expensive mattress. In these situations practitioners may choose to ignore the protocol to reflect “patient choice evidence” over that of research and resource minimization.

As the focus of the embedded model appears to be less on the individual practitioner and more on the evidence products as a means to implementation, then the organizational networks and systems to facilitate their route into practice environments will impact on the extent to which they can be of use there. Often within organizations, the focus becomes “stuck” on these networks and evidence fails to complete the journey into practice if one aspect of the network of distribution or dissemination fails. Review of the (former) Clinical Standards Board for Scotland (CSBS) reports into the implementation of clinical governance (Wilkinson 2008; Wilkinson et al. 2004) identified that in many health-care organizations the focus was on developing verbal and written communication networks but not on considering their effectiveness as a means of seeing evidence used in practice. Even where opportunities existed to develop practice at unit or individual level, based on national evidence products, these were missed.

Reports of use of the Stetler model (McGuire 1990; Reedy et al. 1994) highlight this “sticking of evidence” issue in their recognition that the embedding process took significantly longer than they had anticipated. The development of protocols for drug administration was a lengthy process and was further impeded by concerns raised by practitioners as to some aspects of the protocol. Likewise, use of the Stetler (1994) model to improve bereavement care (Hanson & Ashley 1994) reflected that the evidence-into-practice process took considerably longer than the staff involved had anticipated due to a perceived poor “fit” of evidence to local context and therefore the incorporation of this into local products. However, this latter example illustrates the potential for other impacts or outcomes from the use of this type of model, as it stimulated thinking about inconsistencies in current care provision and as such could be seen to have a conceptual, rather than instrumental impact on care. In addition Hanson and Ashley (1994) report that changes to follow-up practice of the bereaved did take place, but were not based on the evidence reviewed as part of the overall process. This could be viewed as an unintended outcome or impact, but questions remain as to what these changes were based upon, if not evidence and the extent to which the Stetler model assisted such process outcomes?

Although changes to local culture and practice from the use of embedded evidence have been recognized (Wilkinson 2008) this was not by intentional use of a model, nor was it measured in any way, although the impact on patients was seen by practitioners as beneficial. Indeed, in the example identified by Wilkinson (2008) of health-care assistants using a national nursing best-practice statement for the promotion of continence, this resulted from an educational initiative for staff, rather than a specific attempt to promote the use of evidence in practice. This demonstrates that although different models exist, it might be the adoption of other means that have the greater impact on practice. The health-care assistants in this example were unaware that they were using evidence, or promoting the use of evidence by encouraging qualified nurses to follow their lead in managing some evidence-based aspects of care.

The existence of evidence products for embedding is not likely to be enough to have a significant (or even any) impact on practice. There will still be a need for other engagement through, for example, educational and clinical skills development and for favorable organizational contexts (McCormack et al. 2002; Rycroft-Malone et al. 2004) to support their use in practice. The role of monitoring in increasing adherence and identifying positive outcomes for patients through embedded models is not yet known and may not be as straightforward as it would at first appear, as outlined in Chapter 4 of this book. Issues of ownership and the perceived relevance of evidence have the potential to impede embedded models, if the evidence is somehow seen as being disguised to make it more palatable in certain contexts, or if it is presented in candid manner, which might also create tensions around issues of ownership that will influence on the impact of evidence use and cannot be readily addressed by the models.

A summary of the potential impacts from the use of the embedded models is provided in Box 3.5.

Organizational excellence model types

This model type focuses not on individual practitioners, nor on the embedding of evidence products per se, but on wider aspects of the organizations that provide health care. Within these organizations the focus is on leadership, management, and organization to provide the ideal and necessary conditions for evidence use. The role and contribution of professional and ancillary staff is recognized, but it is seen within the wider organizational structures and culture that values, promotes, and enables evidence use. While, on the face of it, some of these features may be seen as reflecting aspects of the embedded evidence model, the focus here is different. The organization is not seen as a mere repository of evidence products, produced elsewhere and provided through the organization for use. Instead, the focus in organizational excellence models is on recognizing complexity, rather than simpler linear models of evidence use. Organizational excellence models often reflect the cyclical and complex nature of evidence use processes, rather than viewing them as straightforward linear, unidirectional ones.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree