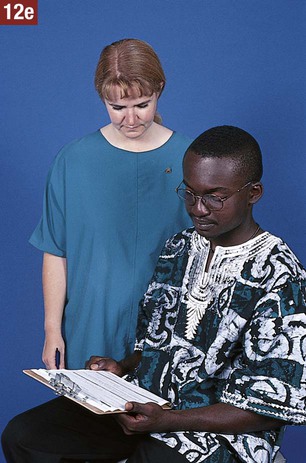

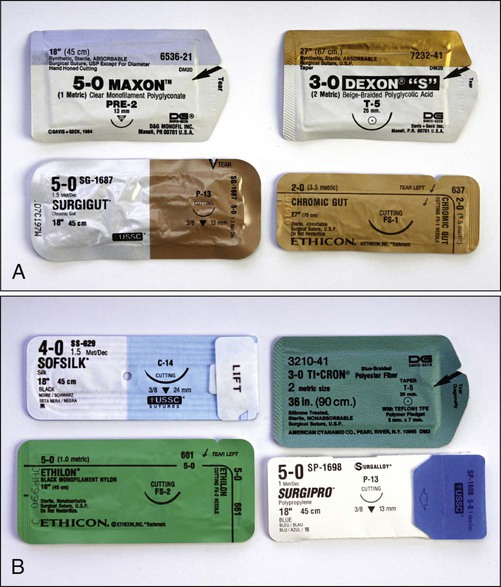

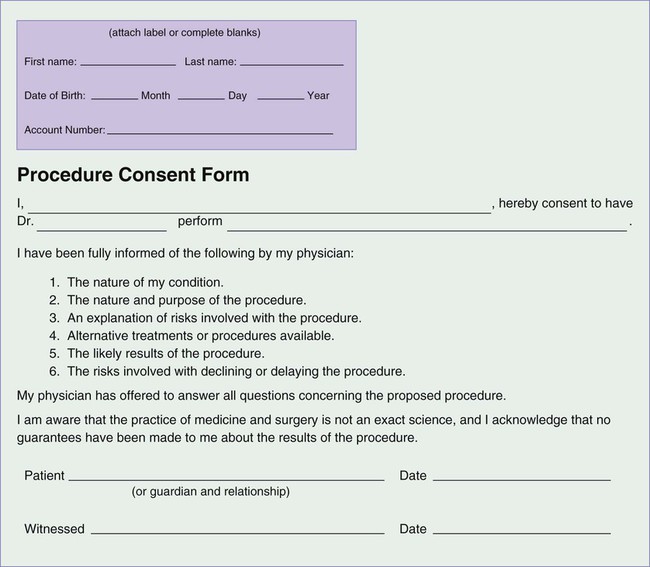

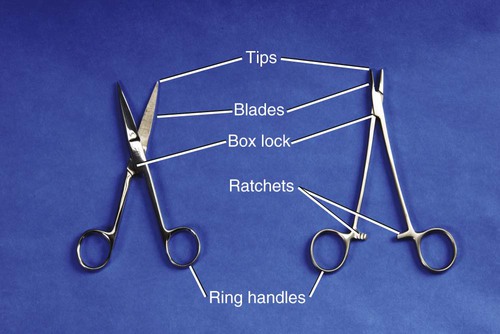

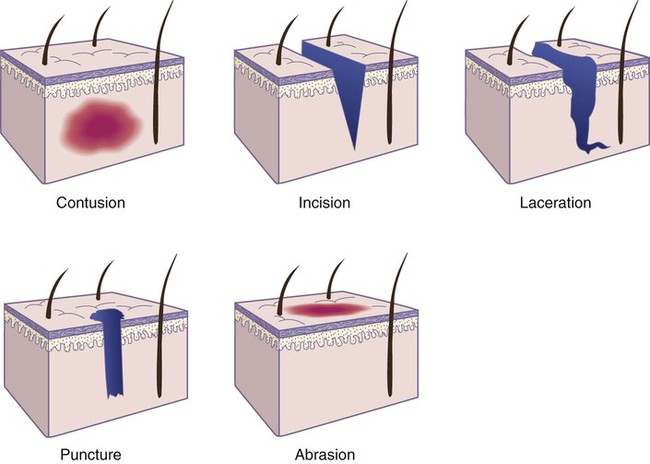

1. State the characteristics of a minor surgical procedure. 2. Identify procedures that require the use of surgical asepsis. 3. Describe the medical assistant’s responsibilities during a minor surgical procedure. 4. List the guidelines to follow to maintain surgical asepsis during a sterile procedure. 5. Identify and explain the use and care of instruments commonly used for minor office surgery. 13. Explain the purpose of and procedure for each of the following minor surgical operations: sebaceous cyst removal, incision and drainage of a localized infection, mole removal, needle biopsy, ingrown toenail removal, colposcopy, cervical punch biopsy, and cryosurgery. 14. Explain the principles underlying each step in the minor office surgery procedures. • Are performed in an ambulatory health care facility, such as a physician’s office or clinic • Can be performed in a short period of time, usually in less than 1 hour • Require a local anesthetic, a topical anesthetic, or no anesthetic • Can be performed safely with a minimum of discomfort to the patient • Do not, under normal circumstances, pose a major risk to life, or function of an organ or body parts Various types of minor surgical operations are performed in the medical office, such as insertion of sutures, sebaceous cyst removal, incision and drainage of infections, mole removal, needle biopsies, cervical biopsies, and ingrown toenail removal. The physician explains the nature of the surgical procedure and any risks to the patient and offers to answer questions. The medical assistant is responsible for explaining the patient preparation required for the procedure and for obtaining the patient’s signature on a written consent to treatment form, which grants the physician permission to perform the surgery (Figure 25-1). Sterility of the hands cannot be attained. Sanitizing the hands renders them medically aseptic and must be performed before and after every surgical procedure using proper technique (see Chapter 17). To prevent contamination of sterile articles, sterile gloves must be worn while picking up or transferring articles during a sterile procedure. Procedure 25-1 describes the procedure for applying and removing sterile gloves. A variety of surgical instruments are used for minor office surgery. Most instruments are made of stainless steel and have either a bright, highly polished finish or a dull finish. The medical assistant should become familiar with the name, use, and proper care of all instruments used in the medical office. Surgical instruments are named by one or more of the following: (1) function (e.g., splinter forceps); (2) design (e.g., mosquito hemostatic forceps); and (3) the individual who developed the instrument (e.g., Kelly hemostatic forceps). The parts of an instrument are illustrated in Figure 25-2; some common instruments are described here and are illustrated in Figure 25-3. Scissors are cutting instruments that have ring handles and straight (str) or curved (cvd) blades. Both blade tips may be sharp (s/s), both may be blunt (b/b), or one tip may be blunt and the other sharp (b/s). The two parts of a pair of scissors come together at a hinge joint known as a box lock (see Figure 25-2). The type of scissors employed depends on the intended use. The various types of scissors are listed and described next. Forceps are instruments for grasping, squeezing, or holding tissue or an item such as sterile gauze. Some forceps have two prongs and a spring handle (e.g., thumb, tissue, splinter, dressing forceps) that provides the proper tension for grasping an object such as tissue, a foreign object, or sterile gauze. Some forceps have serrations (e.g., thumb and hemostatic forceps), which are sawlike teeth that grasp tissue and prevent it from slipping out of the jaws of the instrument. As is shown in Figure 25-3, some varieties have toothed clasps on the handle, known as ratchets (see Figure 25-2), to hold the tips securely together and lock them in place (e.g., Allis tissue forceps, hemostatic forceps). The ratchets are designed to allow locked closure of the instrument at two or more positions. The various types of forceps are listed and described next. Various miscellaneous instruments used in the medical office are listed and described next. 1. Always handle instruments carefully. Dropping an instrument on the floor or throwing an instrument into a basin could damage it. 2. Do not pile instruments in a heap because they become entangled and might be damaged when separated. 3. Keep sharp instruments separate from the rest of the instruments to prevent damaging or dulling the cutting edge. Also, keep delicate instruments, such as lensed instruments, separate to protect them from damage. 4. To prolong the proper functioning of the ratchet, keep instruments with a ratchet in an open position when not in use. 5. Rinse blood and body secretions off an instrument as soon as possible to prevent them from drying and hardening on the instrument. 6. When performing procedures that require surgical instruments, always use the instrument for the purpose for which it was designed. Substituting one type of instrument for another could damage it. 7. Sanitize and sterilize instruments using proper technique. Commercially prepared disposable packages are used frequently and may contain one particular article (e.g., sterile dressing) or a complete sterile setup (e.g., one for the removal of sutures). The directions for opening the package are stated on the outside of the package; they should be followed carefully to prevent contamination of the sterile contents. Procedure 25-2 describes opening a sterile package. One type of commercially prepared package is the peel-apart package (commonly referred to as a peel-pack). This type of sterile package has an edge with two flaps that can be pulled apart in the following manner: Grasp each unsterile flap between your bent index finger and extended thumb, and, rolling your hands outward, pull the package apart (Figure 25-4, A). The inside of the wrapper and the contents are sterile, and to prevent contamination, they must not be touched with the bare hands. The medical assistant can place the contents of the peel-pack directly on the sterile field by stepping back slightly from the field and gently ejecting or “flipping” the contents onto the center of the sterile field (Figure 25-4, B). Stepping back prevents the unsterile outer wrapper and the medical assistant’s hands from crossing over the sterile field, which would result in contamination. The contents of the package also can be removed with a sterile gloved hand. This technique is useful during minor office surgery, when the physician needs additional supplies, such as gauze pads and sutures. The medical assistant opens the sterile package, and the physician removes the sterile contents from the package using a gloved hand (Figure 25-4, C). The inside of the package can be used as a sterile field by opening the peel-apart package completely and laying it flat on a clean dry surface (Figure 25-4, D). Once a sterile package has been opened and set up, the medical assistant may need to pour a sterile solution, such as an antiseptic, into a container located on the field. To do so, the steps of surgical asepsis outlined in Procedure 25-3 should be followed. A closed wound involves an injury to the underlying tissues of the body without a break in the skin surface or mucous membrane; an example is a contusion, or bruise. A contusion results when the tissues under the skin are injured and is often caused by a blunt object. Blood vessels rupture, allowing blood to seep into the tissues, which results in a bluish discoloration of the skin. After several days, the color of the contusion turns greenish yellow as a result of oxidation of blood pigments. Bruising commonly occurs with injuries such as fractures, sprains, strains, and black eyes. Open wounds involve a break in the skin surface or mucous membrane that exposes the underlying tissues; examples include incisions, lacerations, punctures, and abrasions. Figure 25-5 illustrates specific wounds. • An incision is a clean, smooth cut caused by a sharp instrument, such as a knife, razor, or piece of glass. Deep incisions are accompanied by profuse bleeding; in addition, damage to muscles, tendons, and nerves may occur. • A laceration is a wound in which the tissues are torn apart, rather than cut, leaving ragged and irregular edges. Lacerations are caused by dull knives, large objects that have been driven into the skin, and heavy machinery. Deep lacerations result in profuse bleeding, and a scar often results from the jagged tearing of the tissues. • A puncture is a wound made by a sharp-pointed object piercing the skin layers, for example, a nail, splinter, needle, wire, knife, bullet, or animal bite. A puncture wound has a very small external skin opening, and for this reason bleeding is usually minor. A tetanus booster may be administered with this type of wound because the tetanus bacteria grow best in a warm anaerobic environment, such as the one in a puncture. • An abrasion or scrape is a wound in which the outer layers of the skin are scraped or rubbed off, resulting in oozing of blood from ruptured capillaries. Abrasions are often caused by falling on gravel and floors (floor burn). These falls can result in skinned knees and elbows. Nonadherent pads also are used as a sterile dressing; they have one surface impregnated with agents that prevent the dressing from sticking to the wound. One brand of this type of material is Telfa pads. The nonadherent side, which is shiny, is placed next to the wound. Telfa dressings are often used to cover burned skin. Procedure 25-4 presents the procedure for changing a sterile dressing. Absorbable sutures consist of surgical gut (Surgigut) or synthetic materials, such as polyglycolic acid (Dexon), polyglactin 910 (Vicryl), polydioxanone (PDS II), polyglyconate (Maxon), and poliglecaprone (Monocryl), lactomer (Polysorb), and Caprosyn (Figure 25-7, A). Surgical gut is made from sheep or cow intestine. This type of suturing material is gradually digested by tissue enzymes and is absorbed by the body’s tissues 7 to 21 days after insertion, depending on the kind of surgical gut employed. Plain surgical gut has a rapid absorption time, whereas chromic surgical gut is treated to slow down its rate of absorption in the tissues. Absorbable sutures frequently are used to suture subcutaneous tissue, fascia, intestines, bladder, and peritoneum, and to ligate, or tie off, vessels. Because suturing of this type of tissue is generally done during surgery performed by the physician in the hospital with the patient under a general anesthetic, the medical office may not stock absorbable suture material.

Minor Office Surgery

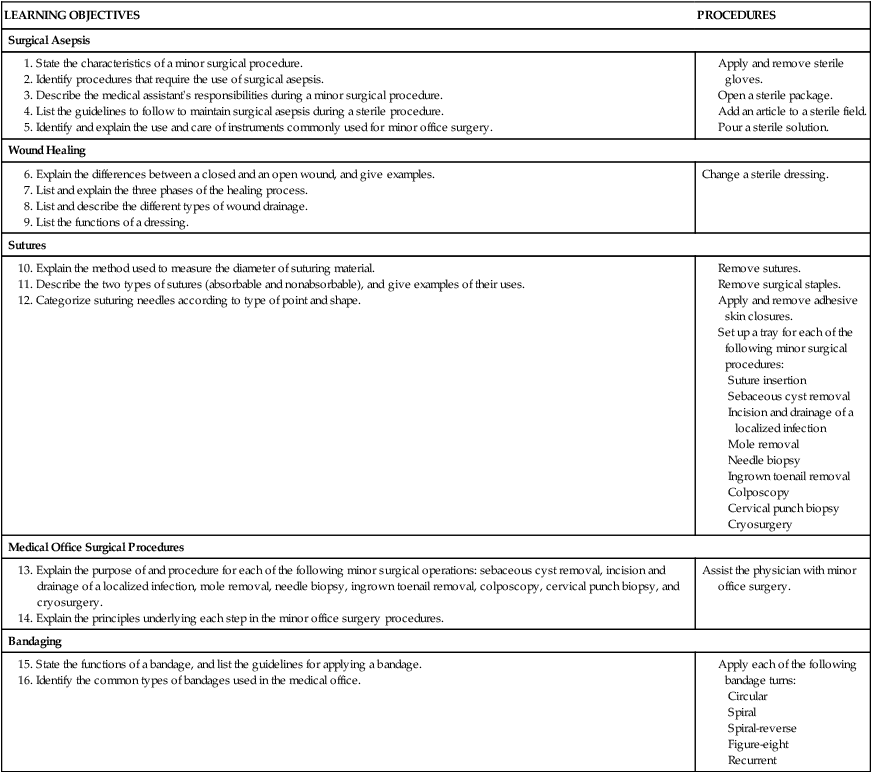

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

PROCEDURES

Surgical Asepsis

Wound Healing

Change a sterile dressing.

Sutures

Medical Office Surgical Procedures

Assist the physician with minor office surgery.

Bandaging

Introduction to Minor Office Surgery

Surgical Asepsis

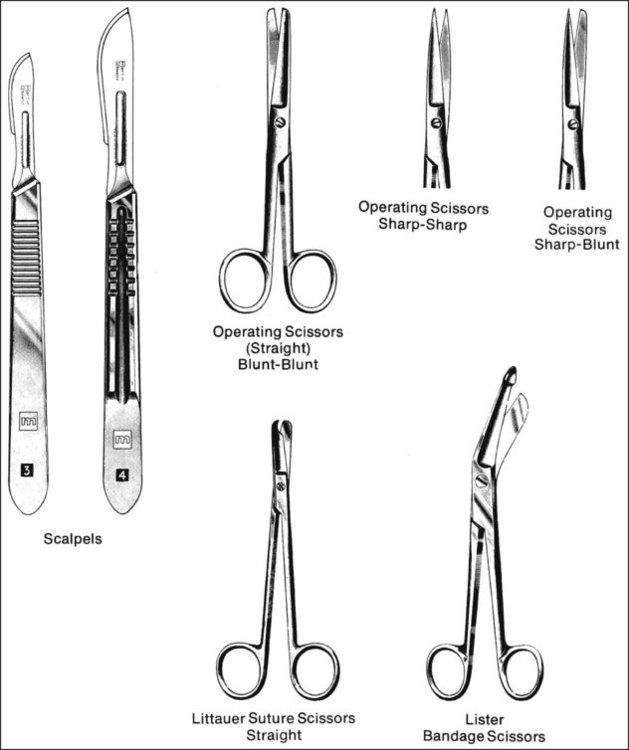

Instruments Used in Minor Office Surgery

Scissors

Operating scissors have straight delicate blades with sharp cutting edges and are used to cut through tissue. They are available with sharp/sharp, blunt/blunt, or blunt/sharp blade tips.

Operating scissors have straight delicate blades with sharp cutting edges and are used to cut through tissue. They are available with sharp/sharp, blunt/blunt, or blunt/sharp blade tips.

Suture scissors are used to remove sutures. The hook on the tip aids in getting under a suture, and the blunt end prevents puncturing of the tissues.

Suture scissors are used to remove sutures. The hook on the tip aids in getting under a suture, and the blunt end prevents puncturing of the tissues.

Bandage scissors are inserted beneath a dressing or bandage to cut it for removal. The flat blunt prow can be inserted beneath a dressing without puncturing the skin.

Bandage scissors are inserted beneath a dressing or bandage to cut it for removal. The flat blunt prow can be inserted beneath a dressing without puncturing the skin.

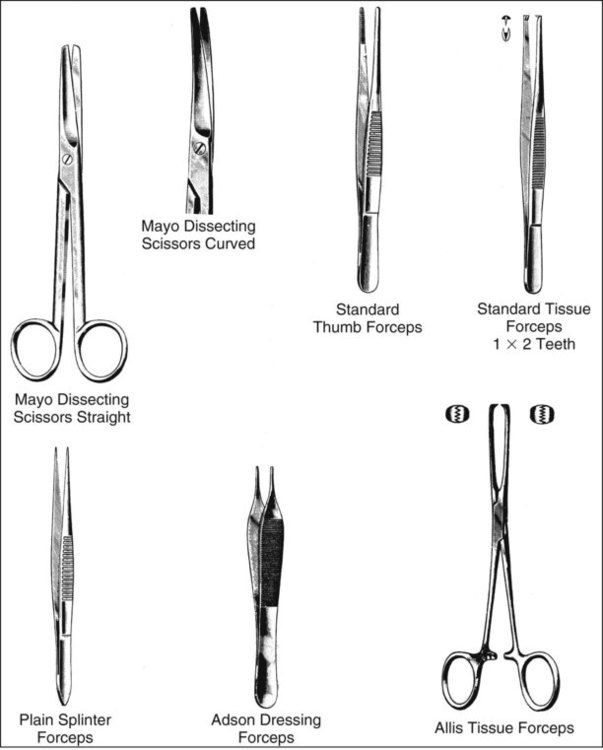

Dissecting scissors have thick beveled blades with a fine cutting edge used to divide or separate tissue rather than cut it. Dissecting scissors are available with straight or curved blades. Both blade tips of dissecting scissors are blunt.

Dissecting scissors have thick beveled blades with a fine cutting edge used to divide or separate tissue rather than cut it. Dissecting scissors are available with straight or curved blades. Both blade tips of dissecting scissors are blunt.

Forceps

Thumb forceps have serrated tips and are used to pick up tissue or to hold tissue between adjacent surfaces.

Thumb forceps have serrated tips and are used to pick up tissue or to hold tissue between adjacent surfaces.

Tissue forceps have teeth, which are used to grasp tissue and prevent it from slipping. Tissue forceps are identified by the number of apposing teeth on each jaw (e.g., 1 × 2, 2 × 3, 3 × 4). Tissue forceps are sometimes referred to as “rat-toothed” forceps because the pointed projections resemble the teeth of a rat. The teeth should approximate tightly when the instrument is closed.

Tissue forceps have teeth, which are used to grasp tissue and prevent it from slipping. Tissue forceps are identified by the number of apposing teeth on each jaw (e.g., 1 × 2, 2 × 3, 3 × 4). Tissue forceps are sometimes referred to as “rat-toothed” forceps because the pointed projections resemble the teeth of a rat. The teeth should approximate tightly when the instrument is closed.

Splinter forceps have sharp points that are useful in removing foreign objects, such as splinters, from the tissues.

Splinter forceps have sharp points that are useful in removing foreign objects, such as splinters, from the tissues.

Dressing forceps are used in the application and removal of dressings. They are also used to hold or grasp sterile gauze or sutures during a surgical procedure. Dressing forceps have blunt ends that contain coarse cross-striations used for grasping.

Dressing forceps are used in the application and removal of dressings. They are also used to hold or grasp sterile gauze or sutures during a surgical procedure. Dressing forceps have blunt ends that contain coarse cross-striations used for grasping.

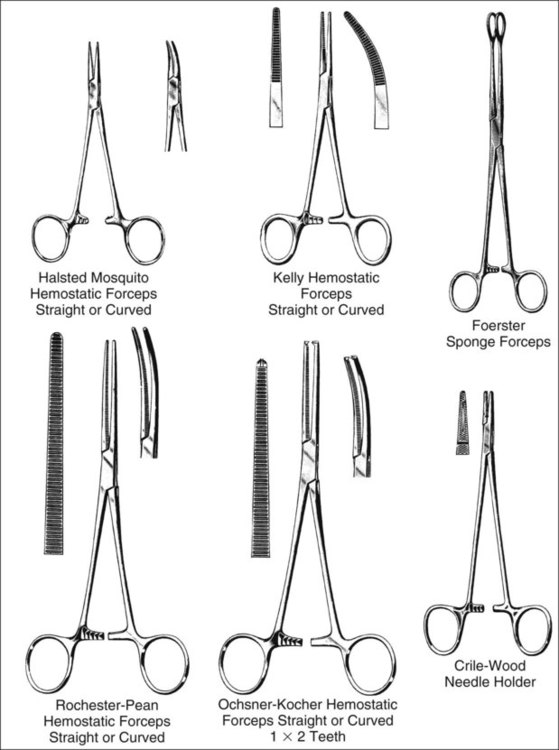

Hemostatic forceps have serrated blades, ratchets, ring handles, and box locks and are available with straight or curved blades. Hemostats are used to clamp off blood vessels and to establish hemostasis until the vessels can be closed with sutures. The serrations on a hemostat prevent the blood vessel from slipping out of the jaws of the instrument. The ratchets keep the hemostat tightly shut and locked in place when it is closed. The ring handles allow for a secure grasp of the hemostat and also are used to select the desired ratchet position. The serrated blades should mesh together smoothly when the hemostat is closed; if they spring back open, the instrument is in need of repair. Mosquito hemostatic forceps have small, fine tips and are smaller and more delicate than standard Kelly hemostatic forceps. Mosquito hemostatic forceps are used to hold delicate tissue or to clamp off smaller blood vessels, whereas standard hemostatic forceps are used to grasp and compress larger blood vessels.

Hemostatic forceps have serrated blades, ratchets, ring handles, and box locks and are available with straight or curved blades. Hemostats are used to clamp off blood vessels and to establish hemostasis until the vessels can be closed with sutures. The serrations on a hemostat prevent the blood vessel from slipping out of the jaws of the instrument. The ratchets keep the hemostat tightly shut and locked in place when it is closed. The ring handles allow for a secure grasp of the hemostat and also are used to select the desired ratchet position. The serrated blades should mesh together smoothly when the hemostat is closed; if they spring back open, the instrument is in need of repair. Mosquito hemostatic forceps have small, fine tips and are smaller and more delicate than standard Kelly hemostatic forceps. Mosquito hemostatic forceps are used to hold delicate tissue or to clamp off smaller blood vessels, whereas standard hemostatic forceps are used to grasp and compress larger blood vessels.

Sponge forceps have ring handles, ratchets, box locks, and large serrated rings on the blade tips for holding sponges. A sponge is a porous, absorbent pad, such as a 4-inch gauze pad, used to absorb fluids, apply medication, or cleanse an area.

Sponge forceps have ring handles, ratchets, box locks, and large serrated rings on the blade tips for holding sponges. A sponge is a porous, absorbent pad, such as a 4-inch gauze pad, used to absorb fluids, apply medication, or cleanse an area.

Miscellaneous Instruments

Needle holders have serrated tips, ring handles, ratchets, and box locks. A needle holder is used to firmly grasp a curved needle for insertion of the needle through the skin flaps of an incision. The serrated tips of a needle holder are designed to hold a curved needle securely without damaging it. A needle holder is sometimes referred to as a “driver” because it functions to “drive” the curved needle through the skin.

Needle holders have serrated tips, ring handles, ratchets, and box locks. A needle holder is used to firmly grasp a curved needle for insertion of the needle through the skin flaps of an incision. The serrated tips of a needle holder are designed to hold a curved needle securely without damaging it. A needle holder is sometimes referred to as a “driver” because it functions to “drive” the curved needle through the skin.

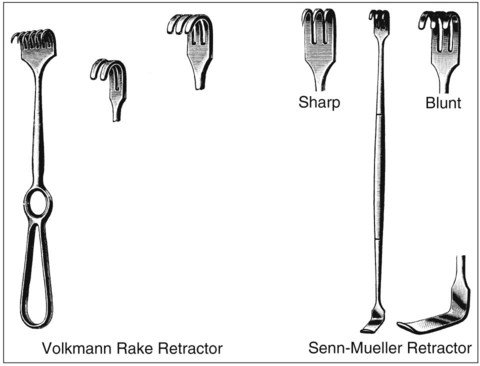

Retractors are used to hold tissues aside to improve the exposure of the operative area.

Retractors are used to hold tissues aside to improve the exposure of the operative area.

Care of Surgical Instruments

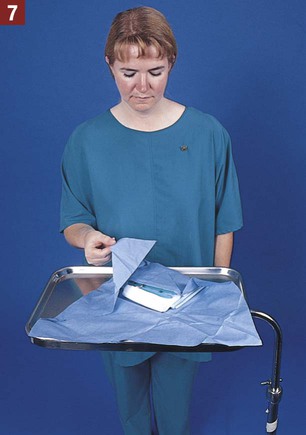

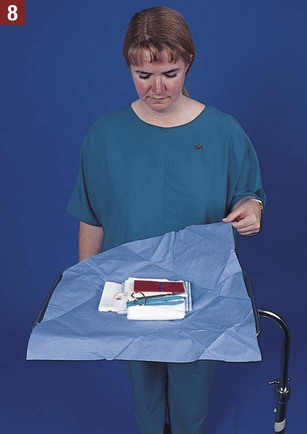

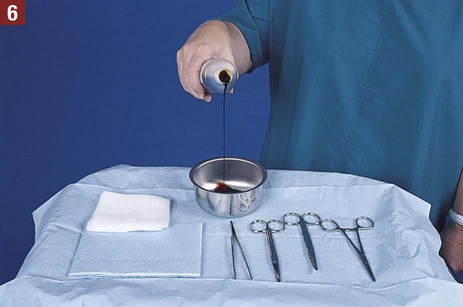

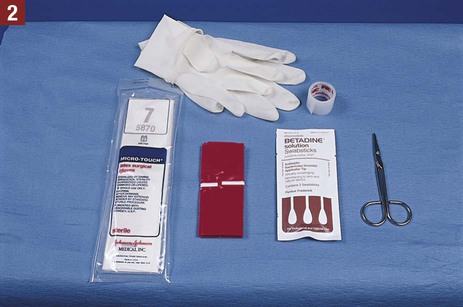

Commercially Prepared Sterile Packages

Wounds

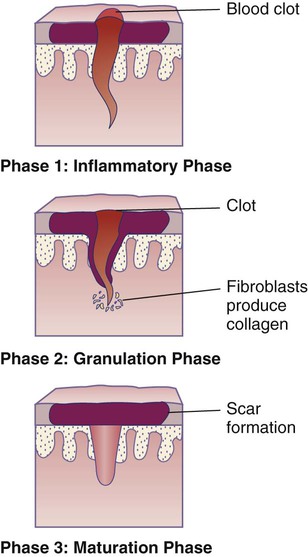

Wound Healing

Wound Drainage

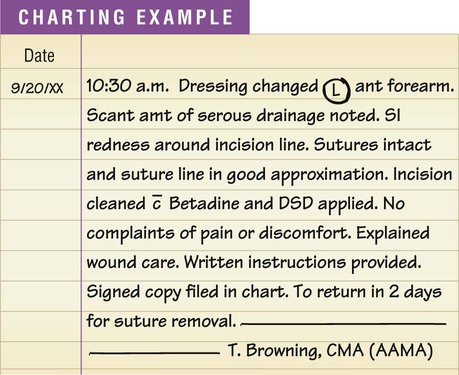

Serous exudate. A serous exudate consists chiefly of serum, which is the clear portion of the blood. Serous drainage is clear and watery. An example of a serous exudate is the fluid in a blister from a burn.

Serous exudate. A serous exudate consists chiefly of serum, which is the clear portion of the blood. Serous drainage is clear and watery. An example of a serous exudate is the fluid in a blister from a burn.

Sanguineous exudate. A sanguineous exudate is red and consists of red blood cells. This type of drainage results when capillaries are damaged, allowing the escape of red blood cells, and is frequently seen in open wounds. A bright-red sanguineous exudate indicates fresh bleeding, and a dark exudate indicates older bleeding.

Sanguineous exudate. A sanguineous exudate is red and consists of red blood cells. This type of drainage results when capillaries are damaged, allowing the escape of red blood cells, and is frequently seen in open wounds. A bright-red sanguineous exudate indicates fresh bleeding, and a dark exudate indicates older bleeding.

Purulent exudate. A purulent exudate contains pus, which consists of leukocytes, dead liquefied tissue debris, and dead and living bacteria. Purulent drainage is usually thick and has an unpleasant odor. It is white in color, but may acquire tinges of pink, green, or yellow depending on the type of infecting organism. The process of pus formation is suppuration.

Purulent exudate. A purulent exudate contains pus, which consists of leukocytes, dead liquefied tissue debris, and dead and living bacteria. Purulent drainage is usually thick and has an unpleasant odor. It is white in color, but may acquire tinges of pink, green, or yellow depending on the type of infecting organism. The process of pus formation is suppuration.

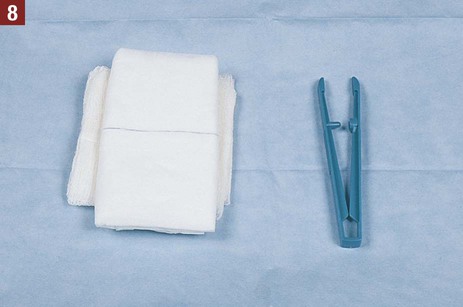

Sterile Dressing Change

Sutures

Types of Sutures

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Minor Office Surgery

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access