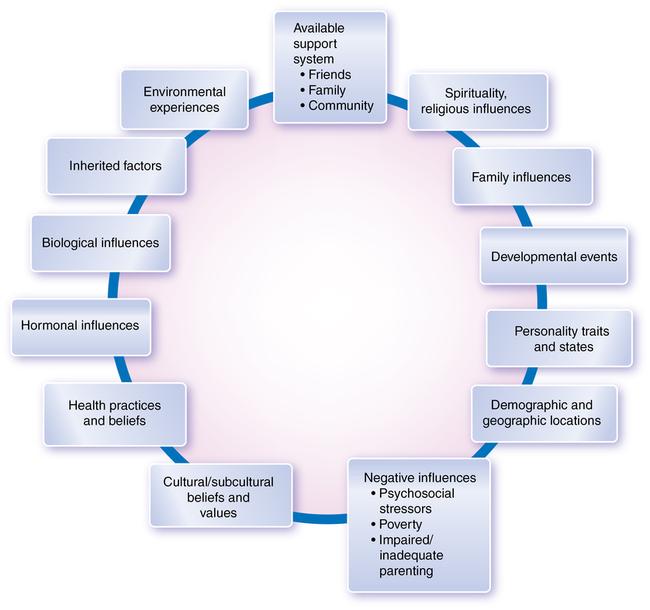

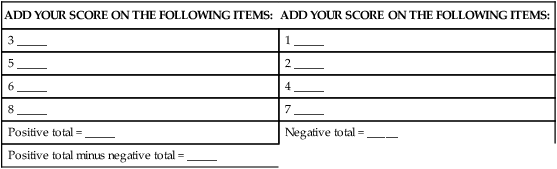

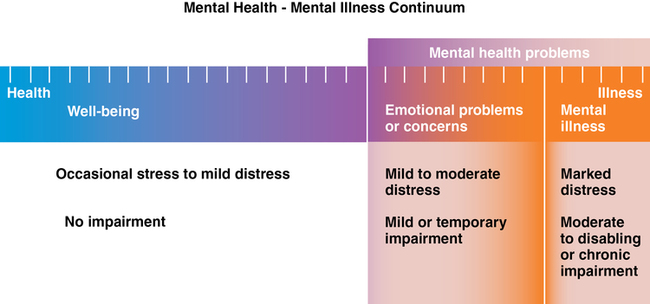

CHAPTER 1 1. Describe the continuum of mental health and mental illness. 2. Explore the role of resilience in the prevention of and recovery from mental illness and consider resilience in response to stress. 3. Identify how culture influences the view of mental illnesses and behaviors associated with them. 4. Discuss the nature/nurture origins of psychiatric disorders. 5. Summarize the social influences of mental health care in the United States. 6. Explain how epidemiological studies can improve medical and nursing care. 7. Identify how the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, fifth edition (DSM-5) is used for diagnosing psychiatric conditions. 8. Describe the specialty of psychiatric mental health nursing and list three phenomena of concern. 9. Compare and contrast a DSM-5 medical diagnosis with a nursing diagnosis. 10. Discuss future challenges and opportunities for mental health care in the United States. 11. Describe direct and indirect advocacy opportunities for psychiatric mental health nurses. advanced practice registered nurse–psychiatric mental health (APRN-PMH) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5) Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC) Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC) psychiatric mental health nursing psychiatry’s definition of mental health registered nurse–psychiatric mental health (RN-PMH) Visit the Evolve website for a pretest on the content in this chapter: http://evolve.elsevier.com/Varcarolis We have come a long way in acknowledging psychiatric disorders and increasing our understanding of them since the days of “nervous breakdowns.” In fact, the World Health Organization (WHO) (2010) maintains that a person cannot be considered healthy without taking into account mental health as well as physical health. The WHO defines mental health as a state of well-being in which each individual is able to realize his or her own potential, cope with the normal stresses of life, work productively, and make a contribution to the community. Mental health provides people with the capacity for rational thinking, communication skills, learning, emotional growth, resilience, and self-esteem (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 1999). Some of the attributes of mentally healthy people are presented in Figure 1-1. You may be wondering if there is some middle ground between mental health and mental illness. After all, it is a rare person who does not have doubts as to his or her sanity at one time or another. The answer is that there is a definite middle ground; in fact, mental health and mental illness can be conceptualized as points along a mental health continuum (Figure 1-2). 1. It was horror and hell. I was at the bottom of the deepest and darkest pit there ever was. I was worthless and unforgivable. I was as good as—no, worse than—dead. 2. I was incredibly alive. I could sense and feel everything. I was sure I could do anything, accomplish any task, create whatever I wanted, if only other people wouldn’t get in my way. 3. Yes, I am sometimes sad and sometimes happy and excited, but nothing as extreme as before. I am much calmer. I realize now that, when I was manic, it was a pressure-cooker feeling. When I am happy now, or loving, it is more peaceful and real. I have to admit that I sometimes miss the intensity—the sense of power and creativity—of those manic times. I never miss anything about the depressed times, but of course the power and the creativity never bore fruit. Now I do get things done, some of the time, like most people. And people treat me much better now. I guess I must seem more real to them. I certainly seem more real to me (Altrocchi, 1980). Many factors can affect the severity and progression of a mental illness as well as the mental health of a person who does not have a mental illness (Figure 1-3). If possible, these influences need to be evaluated and factored into an individual’s plan of care. In fact, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5), a 1.5-inch-thick manual that classifies 157 separate disorders, states that there is evidence suggesting that the symptoms and causes of a number of disorders are influenced by cultural and ethnic factors (APA, 2013). The DSM-5 is discussed in further detail later in this chapter. Researchers, clinicians, and consumers are all interested in actively facilitating mental health and reducing mental illness. A characteristic of mental health, increasingly being promoted and essential to the recovery process, is resilience. Resilience is closely associated with the process of adapting and helps people facing tragedies, loss, trauma, and severe stress. It is the ability and capacity for people to secure the resources they need to support their well-being, such as children of poverty and abuse seeking out trusted adults who provide them with the psychological and physical resources that allow them to excel. This social support actually brings about chemical changes in the body through the release of oxytocin, which mutes the destructive stress-related chemicals (Southwick & Charney, 2012). Accessing and developing this trait assists people in bouncing back from painful experiences and difficult events; it is characterized by optimism, a sense of mastery, and competence (Southwick & Charney, 2012). It is not an unusual quality; it is possessed by regular, everyday people and can be enhanced in almost everyone. One of the most important qualities is the ability to identify the problems and challenges, accepting those things that cannot be changed and then focusing on what can be overcome. Research demonstrates that early experiences in mastering difficult or stressful situations enhance the prefrontal cortex’s resiliency in coping with difficult situations later. According to Amat and colleagues (2006), when rats were exposed to uncontrollable stresses, their brains turned off mood-regulating cells, and they developed a syndrome much like major depression. Rats that were first given the chance to control a stressful situation were better able to respond to subsequent stress for up to a week following the success. In fact, when the successful rats were faced with uncontrollable stress, their brain cells responded as if they were in control. People who are resilient are effective at regulating their emotions and not falling victim to negative, self-defeating thoughts. You can get an idea of how good you are at regulating your emotions by taking the Resilience Factor Test in Box 1-1. Throughout history, people have interpreted health or sickness according to their own current views. A striking example of how cultural change influences the interpretation of mental illness is an old definition of hysteria. According to Webster’s Dictionary (Porter, 1913), hysteria was “A nervous affection, occurring almost exclusively in women, in which the emotional and reflex excitability is exaggerated, and the will power correspondingly diminished, so that the patient loses control over the emotions, becomes the victim of imaginary sensations, and often falls into paroxysm or fits.” Treatment for this condition, thought to be the result of sexual deprivation, often involved sexual outlets for afflicted women. According to some authors, this diagnosis fell into disuse as women’s rights improved, the family atmosphere became less restrictive, and societal tolerance of sexual practices increased. Cultures differ in not only their views regarding mental illness but also the types of behavior categorized as mental illness. Culture-bound syndromes seem to occur in specific sociocultural contexts and are easily recognized by people in those cultures (Stern et al., 2010). For example, one syndrome recognized in parts of Southeast Asia is running amok, in which a person (usually a male) runs around engaging in almost indiscriminate violent behavior. Pibloktoq, an uncontrollable desire to tear off one’s clothing and expose oneself to severe winter weather, is a recognized psychological disorder in parts of Greenland, Alaska, and the Arctic regions of Canada. In the United States, anorexia nervosa (see Chapter 18) is recognized as a psychobiological disorder that entails voluntary starvation. The disorder is well known in Europe, North America, and Australia but unheard of in many other parts of the world. What is to be made of the fact that certain disorders occur in some cultures but are absent in others? One interpretation is that the conditions necessary for causing a particular disorder occur in some places but are absent in other places. Another interpretation is that people learn certain kinds of abnormal behavior by imitation; however, the fact that some disorders may be culturally determined does not prove that all mental illnesses are so determined. The best evidence suggests that schizophrenia (see Chapter 12) and bipolar disorders (see Chapter 13) are found throughout the world. The symptom patterns of schizophrenia have been observed in Western culture and among indigenous Greenlanders and West African villagers. For students, one of the most intriguing aspects of learning about mental illnesses is understanding their origins. Although for centuries people believed that extremely unusual behaviors were due to demonic forces, in the late 1800s, the mental health pendulum swung briefly to a biological focus with the “germ theory of diseases.” Germ theory explained mental illness in the same way other illnesses were being described—that is, they were caused by a specific agent in the environment (Morgan, McKenzie, & Fearon, 2008). This theory was abandoned rather quickly since clinicians and researchers could not identify single causative factors for mental illnesses; there was no “mania germ” that could be viewed under a microscope and subsequently treated. The consumer movement also promoted the notion of recovery, a new and an old idea in mental health. On one hand, it represents a concept that has been around a long time: that some people—even those with the most serious illnesses, such as schizophrenia—recover. One such recovery was depicted in the movie “A Beautiful Mind,” wherein a brilliant mathematician, John Nash, seems to have emerged from a continuous cycle of devastating psychotic relapses to a state of stabilization and recovery (Howard, 2001). On the other hand, a newer conceptualization of recovery evolved into a consumer-focused process “in which people are able to live, work, learn, and participate fully in their communities” (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2003). According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) (2011), recovery is defined as “a process of change through which individuals improve their health and wellness, live a self-directed life, and strive to reach their full potential.” The focus is on the consumer and what he or she can do. An example of recovery follows: • Understanding the genetic basis of embryonic and fetal neural development • Mapping genes involved in neurological illnesses, including mutations associated with Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and epilepsy • Discovering that the brain uses a relatively small number of neurotransmitters but has a vast assortment of neurotransmitter receptors • Uncovering the role of cytokines (proteins involved in the immune response) in such brain disorders as depression • Refining neuroimaging techniques, such as positron emission tomography (PET) scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), magnetoencephalography, and event-related electroencephalography (EEG), has improved our understanding of normal brain functioning as well as areas of difference in pathological states • Bringing together computer modeling and laboratory research, which resulted in the new discipline of computational neuroscience. The first Surgeon General’s report on the topic of mental health was published in 1999 (USDHHS, 1999). This landmark document was based on an extensive review of the scientific literature in consultation with mental health providers and consumers. The two most important messages from this report were that (1) mental health is fundamental to overall health, and (2) there are effective treatments for mental health. The report is reader-friendly and a good introduction to mental health and illness. You can review the report at http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/mentalhealth/home.html. The Human Genome Project was a 13-year project that lasted from 1990–2003 and was completed on the 50th anniversary of the discovery of the DNA double helix. The project has strengthened biological and genetic explanations for psychiatric conditions (Cohen, 2000). The goals of the project (U.S. Department of Energy, 2008) were to do the following: • Identify the approximately 20,000 to 25,000 genes in human DNA. • Determine the sequences of the 3 billion chemical base pairs that make up human DNA. • Store this information in databases. • Improve tools for data analysis. • Address the ethical, legal, and social issues that may arise from the project.

Mental health and mental illness

Continuum of mental health and mental illness

Contributing factors

Resilience

Culture

Perceptions of mental health and mental illness

Mental illness versus physical illness

Nature versus nurture

Social influences on mental health care

Consumer movement and mental health recovery

Decade of the brain

Surgeon general’s report on mental health

Human genome project

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Mental health and mental illness

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access