Apply the rights of medication administration in the care of a patient.

Illustrate knowledge needed to administer medications to a patient.

Illustrate knowledge needed to administer medications to a patient.

Identify and interpret the drug orders for medication administration.

Identify and interpret the drug orders for medication administration.

Demonstrate the ability to calculate drug dosages accurately.

Demonstrate the ability to calculate drug dosages accurately.

Apply the steps of the nursing process in the administration of medications.

Apply the steps of the nursing process in the administration of medications.

Demonstrate safe and accurate administration of medications.

Demonstrate safe and accurate administration of medications.

Apply evidence-based practice research in the administration of medications.

Apply evidence-based practice research in the administration of medications.

Identify alternative or complementary therapy that may potentiate, negate, or cause toxicity with prescribed medications.

Identify alternative or complementary therapy that may potentiate, negate, or cause toxicity with prescribed medications.

Clinical Application Case Study

Jacqueline Baranski has been admitted to the hospital for a total abdominal hysterectomy. This is the first postoperative day. She is currently taking lisinopril 10 mg PO daily and estradiol 1 mg PO. She is also receiving morphine sulfate by patient-controlled analgesia and heparin 5000 units subcutaneously every 12 hours for 7 days.

KEY TERMS

Assessment: collection of patient data that affects drug therapy

Controlled-release: oral tablet or capsule formulations that maintain consistent serum drug levels

Dosage form: form in which drugs are manufactured; includes elixirs, tablets, capsules, suppositories, parenteral drugs, and transdermal systems

Enteric-coated: coating of a tablet or capsule that makes it insoluble in stomach acid

Evaluation: determining a patient’s status in relation to stated goals and expected outcomes

Evidence-based practice: scientific evidence that yields the best practice in patient care

Interventions: planned nursing activities performed on a patient’s behalf, including assessment, promotion of adherence to drug therapy, and solving problems related to drug therapy

Medication history: list of prescription medications, over-the-counter medications, herbal supplements, or illegal substances taken by the patient (both current and past)

Nursing diagnosis: description of patient problems based on assessment data

Nursing process: systematic way of gathering and using information to plan and provide individualized patient care

Parenteral: injected administration; subcutaneous, intramuscular, or intravenous route

Planning/goals: expected outcomes of prescribed drug therapy

Rights of medication administration: assist to ensure accuracy in drug therapy; rights include right drug, right dose, right patient, right route, right time, right reason, and right documentation

Topical: application of drugs (e.g., solutions, ointments, creams, or suppositories) to skin or mucous membranes

Transdermal: absorption of drugs (e.g., skin patches) through the skin

This chapter discusses the administration of medications and the implementation of the nursing process with medication administration. The purpose of administering medications is to evoke a therapeutic response. Giving medications to a patient is an important nursing responsibility in many health care settings, including ambulatory clinics, hospitals, long-term care facilities, schools, and in homes. The basic requirements for accurate drug administration are the rights of medication administration, which are:

• Right drug

• Right dose

• Right patient

• Right route

• Right time

• Right reason

• Right documentation

These “rights” require knowledge of the drugs to be given and the patients who are to receive them as well as specific nursing skills and interventions. The implementation of the nursing process in the administration of medications provides a systematic way of gathering and using information to plan and provide individualized patient care as well as to evaluate the outcomes of that care. It involves both cognitive and psychomotor skills. Knowledge of, and skill in, the nursing process is required for drug therapy as in other aspects of patient care. The five steps of the nursing process are assessment, nursing diagnosis, planning and establishing goals for care, interventions, and evaluation as it is applied to medication administration.

General Principles of Accurate Drug Administration

The nurse adheres to the following principles:

• Follow the “rights” associated with medication administration consistently.

• Learn essential information about each drug to be given (e.g., indications for use, contraindications, therapeutic effects, adverse effects, any specific instructions about administration).

• Interpret the prescriber’s order accurately (i.e., drug name, dose, frequency of administration). Question the prescriber if any information is unclear or if the drug seems inappropriate for the patient’s condition.

• In the event a verbal or telephone order is given by a prescriber, write down the order or enter it in the computer and then read the order back to the prescriber.

• Read labels of drug containers for the drug name and concentration (usually in milligrams per tablet, capsule, or milliliter of solution). Many medications are available in different dosage forms and concentrations, and it is extremely important to use the correct ones.

• Use only approved abbreviations for drug names, doses, routes of administration, and times of administration. For example, do not use U to refer to units. Instead, write out units. This promotes safer administration and reduces errors. Consult the “Do Not Use” list, the safety guidelines published by the Joint Commission (see Table 1.4). Check the organization’s Web site for details.

• Calculate doses accurately. Current nursing practice requires few dosage calculations (most are done by pharmacists). However, when they are needed, accuracy is essential. For medications with a narrow safety margin or potentially serious adverse effects, ask a pharmacist or a colleague to do the calculation also and compare the results. This is especially important when calculating children’s dosages.

• Measure doses accurately. Ask a colleague to double-check measurements of insulin and heparin, unusual doses (i.e., large or small), and any drugs to be given intravenously.

• Use the correct procedures and techniques for all routes of administration. For example, use appropriate anatomic landmarks to identify sites for intramuscular (IM) injections, follow the manufacturers’ instructions for preparation and administration of intravenous (IV) medications, and use sterile materials and techniques for injectable and eye medications.

• Seek information about the patient’s medical diagnoses and condition in relation to drug administration (e.g., ability to swallow oral medications; allergies or contraindications to ordered drugs; new signs or symptoms that may indicate adverse effects of administered drugs; heart, liver, or kidney disorders that may interfere with the patient’s ability to distribute, metabolize, or eliminate drugs).

• Verify the identity of all patients before administering medications; check identification bands on patients who have them (e.g., in hospitals or long-term care facilities).

• Omit or delay doses as indicated by the patient’s condition and report or record omissions appropriately.

• Be especially vigilant when giving medications to children because there is a high risk of medication errors. One reason is children’s great diversity in age, from birth to 18 years, and in weight, from 2 to 3 kg to 100 kg or more. A second reason is that most drugs have not been tested in children. A third reason is that many drugs are marketed in dosage forms and concentrations suitable for adults. This often requires dilution, calculation, preparation, and administration of very small doses. A fourth reason is that children have limited sites for administration of IV drugs, and several may be given through the same site. In many cases, the need for small volumes of fluid limits flushing between drugs (which may produce undesirable interactions with other drugs and IV solutions).

Clinical Application 3-1

Prior to administering the medications to Ms. Baranski, how does the nurse incorporate the rights of medication administration into the patient’s care?

Prior to administering the medications to Ms. Baranski, how does the nurse incorporate the rights of medication administration into the patient’s care?

Why is the Joint Commission’s “Do Not Use” list so important in the prevention of medication administration errors?

Why is the Joint Commission’s “Do Not Use” list so important in the prevention of medication administration errors?

NCLEX Success

1. A physician writes an order using the abbreviation MS. The order states “MS 10 mg IV push every 6 hours as needed for pain.” According to the Joint Commission’s “Do Not Use” list, what is the potential problem in this order?

A. The order does not include a dosage.

B. The drug could be magnesium sulfate or morphine sulfate.

C. The potential problem is minimal, and the order is clear.

D. The order does not include the route.

2. A prescriber has written an order for an oral medication to a patient following a cerebrovascular accident (stroke). Prior to administering the medication, which of the following nursing interventions is most important?

A. allowing the patient to take the medication with thickened liquids

B. placing the patient in the sitting position

C. assessing the patient’s blood pressure and pulse

D. assessing the patient’s ability to swallow

Legal Responsibilities

Registered and licensed practical nurses are legally empowered, under state nurse practice acts, to give medications ordered by licensed physicians and dentists. In some states, nurse practitioners may prescribe medications.

When giving medications, the nurse is legally responsible for safe and accurate administration. This means that the nurse may be held liable for not giving a drug or for giving a wrong drug or a wrong dose. In addition, the nurse is expected to have sufficient drug knowledge to recognize and question erroneous orders. If, after questioning the prescriber and seeking information from other authoritative sources, the nurse considers that giving a drug is unsafe, the nurse must refuse to give the drug. The fact that a physician wrote an erroneous order does not excuse the nurse from legal liability if he or she carries out that order.

The nurse also is legally responsible for actions delegated to people who are inadequately prepared for or legally barred from administering medications (e.g., nursing assistants). However, certified medical assistants (CMAs) may administer medications in physicians’ offices, and certified medication aides (nursing assistants with a short course of training, also called CMAs) often administer medications in long-term care facilities.

The nurse who consistently follows safe practices in giving medications does not need to be excessively concerned about legal liability. The basic techniques and guidelines described in this chapter are aimed at safe and accurate preparation and administration. Most errors result when these practices are not followed.

Legal responsibilities in other aspects of drug therapy are less clear-cut. However, in general, nurses are expected to monitor patients’ responses to drug therapy (e.g., therapeutic and adverse effects) and to teach patients safe and effective self-administration of drugs when indicated.

Medication Errors and their Prevention

Medication errors continue to receive increasing attention from numerous health care organizations and agencies. Much of this interest stems from a 1999 report of the Institute of Medicine (IOM), which estimated that 44,000 to 98,000 deaths occur each year in the United States because of medical errors, including medication errors. The 2004 report of the IOM, Keeping Patients Safe: Transforming the Work Environment of Nurses, reported that the extended hours nurses work contributes to medication errors. Potential adverse patient outcomes of medication and other errors include serious illness, conditions that prolong hospitalization or require additional treatment, and death. Medication errors commonly reported include giving an incorrect dose, not giving an ordered drug, and giving an unordered drug. Specific drugs often associated with errors and adverse drug events (ADEs) include insulin, heparin, and warfarin. The risk of ADEs increases with the number of drugs a patient uses.

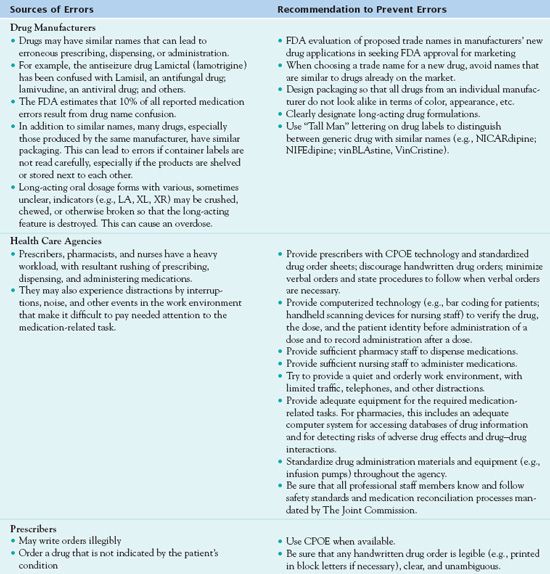

Medication errors may occur at any step in the drug distribution process, from the manufacturer to the patient, including prescribing, transcribing, dispensing, and administering. Many steps and numerous people are involved in giving the correct dose of a medication to the intended patient; each step or person has a potential for contributing to a medication error or preventing a medication error. All health care providers involved in drug therapy need to recognize risky situations, intervene to prevent errors when possible, and be extremely vigilant in all phases of drug administration. Recommendations for prevention of medication errors have been developed by several organizations, including the IOM, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the Joint Commission, the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), and the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCCMERP). Some sources of medication errors and recommendations to prevent them are summarized in Table 3.1.

CPOE, computerized provider order entry; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

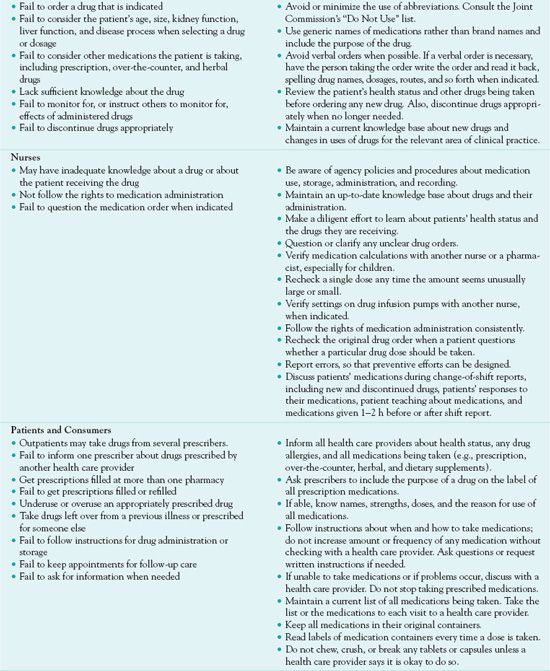

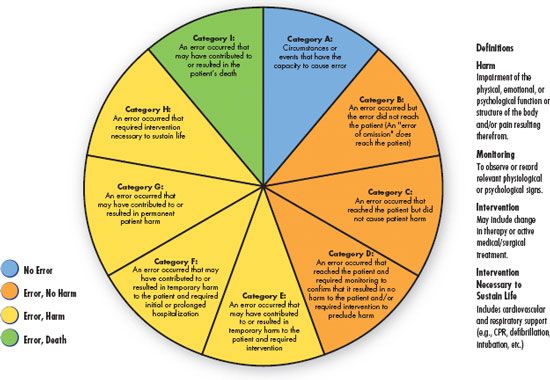

The NCCMERP has developed an index for categorizing medication errors (Fig. 3.1) and an algorithm (Fig. 3.2). This categorization of medication errors can be adopted by health care institutions. Using the A through I, this system ranks medication errors according to the severity of their outcomes. Category A identifies circumstances that have the capacity to cause an error, and category I identifies an error that contributed to a patient’s death. This system gives health care institutions the ability to track the rate of medication errors.

Figure 3.1 Index for categorizing medication errors, National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention. http://www.nccmerp.org/pdf/index-Color2001-06-12.pdf ©2001 National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention. All rights reserved.

Figure 3.2 Algorithm for categorizing medication errors, National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention. http://www.nccmerp.org/pdf/algor-Color2001-06-12.pdf ©2001 National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention. All rights reserved.

Medication Systems

Each health care facility has a system for distributing drugs. The unit–dose system, in which most drugs are dispensed in single-dose containers for individual patients, is widely used. The pharmacist or pharmacy technician checks drug orders and stocks the medication in the patient’s medication drawer. When a dose is due to be taken, the nurse removes the medication and gives it to the patient. Unit–dose wrappings of oral drugs should be left in place until the nurse is in the presence of the patient and ready to give the medication. It is essential that each dose of a drug be recorded on the patient’s medication administration record (MAR) as soon as possible after administration.

Increasingly, institutions are using automated, computerized, locked cabinets for which each nurse on a unit has a password or code for accessing the cabinet and obtaining a drug dose. The pharmacy maintains the medications and replaces the drug when needed.

Controlled drugs, such as opioid analgesics, are usually kept as a stock supply in a locked drawer or automated cabinet and replaced as needed. The nurse must sign for each dose and record it on the patient’s MAR. He or she must comply with legal regulations and institutional policies for dispensing and recording controlled drugs.

Changes to Prevent Medication Errors

Changes in medication systems are being increasingly implemented, largely in efforts to decrease medication errors and improve patient safety. These include the following:

• Computerized provider order entry (CPOE). In this system, a prescriber types a medication order directly into a computer. This decreases errors associated with illegible handwriting and erroneous transcription or dispensing. CPOE, which is already used in many health care facilities, is widely recommended as the preferred alternative to error-prone handwritten orders.

• Bar coding. In 2004, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) passed a regulation requiring drug manufacturers to put bar codes on current prescription medications and nonprescription medications that are commonly used in hospitals. New drugs must have bar codes within 60 days of their approval. In hospitals, bar codes operate with other agency computer systems and databases that contain a patient’s medication orders and MAR. The bar code on the drug label contains the identification number, strength, and dosage form of the drug, and the bar code on the patient’s identification band contains the MAR, which can be displayed when a nurse uses a handheld scanning device. When administering medications, the nurse scans the bar code on the drug label, on the patient’s identification band, and on the nurse’s personal identification badge. A wireless computer network processes the scanned information; gives an error message on the scanner or sounds an alarm if the nurse is about to give the wrong drug or the right drug at the wrong time; and automatically records the time, drug, and dose given on the MAR. The FDA estimates that it will take about 20 years for all US hospitals to implement this system of bar codes for medication administration.

For nurses, implementing the bar coding technology increases the time requirements and interferes with their ability to individualize patient care in relation to medications. Such a system works well with routine medications, but non-routine situations (e.g., variable doses or times of administration) may pose problems. In addition, in long-term care facilities, it may be difficult to maintain legible bar codes on patient identification bands. Despite some drawbacks, bar coding increases patient safety, and therefore, nurses should support its development.

• Point-of-care. The point-of-care bar code-assisted software was developed in August 1999 by the Department of Veterans Affairs for the department’s medical centers. Point-of-care is the time in which the nurse scans the bar-coded medication administered to the patient (Mims, Tucker, Carlson, Schneider, & Bagby, 2009). This system uses bar code scanning that verifies the right drug, dose, patient, route, and time. The reason for the medication and subsequent documentation is the responsibility of the nurse administering the medication. This technology increases patient safety and accuracy of reporting. Using a handheld electronic device, the nurse scans the bar code and compares the medication being administered with what was ordered for the patient. Following receipt of the written order, the pharmacist enters, verifies, and profiles the order. Prior to administering the medication, the nurse confirms a match between the written and electronically profiled order. Before administering the medication, the nurse scans the patient’s wristband and medication. The device then verifies that it is the correct dose, correct time, and correct patient (Fowler, Sohler, & Zarillo, 2009).

• Limiting use of abbreviations. The ISMP has long maintained a list of abbreviations that are often associated with medication errors, and the Joint Commission requires accredited organizations to maintain a “Do Not Use” list (e.g., u or U for units, IU for international units, qd for daily, qod for every other day) that applies to all prescribers and transcribers of medication orders. Other abbreviations are not recommended as well. In general, it is safer to write out drug names, routes of administration, and so forth and to minimize the use of abbreviations, symbols, and numbers that are often misinterpreted, especially when handwritten.

• Medication reconciliation. This is a process designed to avoid medication errors such as omissions, duplications, dosing errors, or drug interactions that occur when a patient is admitted to a health care facility, transferred from one department or unit to another within the facility, or discharged home from the facility. It involves obtaining an accurate medication history about all drugs (both prescription and over-the-counter [OTC]), vitamins, and herbal medications taken at home, including dose and frequency of administration, on entry into the health care facility (see later discussion). The list of medications developed from the medication history is compared to newly ordered medications, and identified discrepancies are resolved. The list is placed in the medical record so that it is accessible to all health care providers, including the prescriber who writes the patient’s admission drug orders. When the patient is transferred, the updated list must be communicated to the next health care provider. When a patient is discharged, an updated list should be given to the next provider and to the patient. The patient should be encouraged to keep the list up-to-date when changes are made in the medication regimen and to share the list with future health care providers.

Bar Code Technology for Medication Administration: Medication Errors and Nurse Satisfaction

by SUSAN FOWLER, PHD, RN, CNRN, PATRICIA SOHLER, MA, RN, & DOROTHY ZARILLO, MSN, RN

CNAA March-April 2009, 18(2):103-109

A study determining the satisfaction nursing have regarding the implementation of the bar coding system using point-of-care technology was conducted in 2007 on a 53-bed medical-surgical unit with a step-down area. The study used the Medications Administration System-Nurses Assessment of Satisfaction. The nurses reported the highest satisfaction focused on checks completed by pharmacists but dissatisfaction with the turnaround time for stat medications. Six months after the adoption of the system, nurses were satisfied that the system made it easier to check the five rights of medication administration. Nurses reported they were most satisfied with the system’s safety but least satisfied with not having more time to spend with their patients. The investigators noted that the category C errors increased after the implementation of the system. This may relate to increased awareness, better reporting, and more assistance in the reporting process.

IMPLICATIONS FOR NURSING PRACTICE: The implementation of point-of-care medication administration systems using bar codes allows for greater safety in medication administration. However, the profiling step in the process delays the administration of “stat” medications.

Clinical Application 3-2

The nurse is checking Ms. Baranski’s patient-controlled analgesia of morphine sulfate. The medication cartridge is empty and needs to be changed. What are the nurse’s legal responsibilities when changing an opioid medication?

The nurse is checking Ms. Baranski’s patient-controlled analgesia of morphine sulfate. The medication cartridge is empty and needs to be changed. What are the nurse’s legal responsibilities when changing an opioid medication?

What nursing interventions prevent medication errors?

What nursing interventions prevent medication errors?

NCLEX Success

3. A prescriber has written an order for levothyroxine sodium (Synthroid) 50 mg per day by mouth. The nurse knows that the standard dose is 50 mcg. What action should the nurse take?

A. Call the prescriber and question the order.

B. Administer 50 mcg instead.

C. Consult the pharmacist about the order.

D. Ask the patient what he or she usually takes.

4. The nurse is administering the first dose of an anti-infective agent. Which of the following assessments should the nurse make prior to administering the anti-infective agent?

A. Assess the patient’s temperature.

B. Assess the patient’s level of consciousness.

C. Assess if the patient is allergic to any anti-infective agent.

D. Assess if the patient has taken the medication previously.

5. Which of the following nursing actions will prevent adverse drug events?

A. Use only the trade name when documenting medications.

B. Crush long-acting medications if the patient has dysphagia.

C. After receiving a verbal order, administer the medication and then write down the order.

D. Use bar code technology according to institutional policy.

Medication Orders

Medication orders should include the full name of the patient; the name of the drug (preferably the generic name); the dose, route, and frequency of administration; and the date, time, and signature of the prescriber.

Orders in a health care facility may be typed into a computer (the preferred method) or handwritten on an order sheet in the patient’s medical record. Occasionally, verbal or telephone orders are acceptable. When taken, they should be written on the patient’s order sheet, signed by the person taking the order, and later countersigned by the prescriber. After the order is written, a copy is sent to the pharmacy, where the order is recorded and the drug is dispensed to the appropriate patient care unit. In many facilities, pharmacy staff prepares a computer-generated MAR for each 24-hour period.

For patients in ambulatory care settings, the procedure is essentially the same for drugs to be given immediately. For drugs to be taken at home, written prescriptions are given. In addition to the previous information, a prescription should include instructions for taking the drug (e.g., dose, frequency) and whether the prescription can be refilled. Prescriptions for Schedule II controlled drugs cannot be refilled.

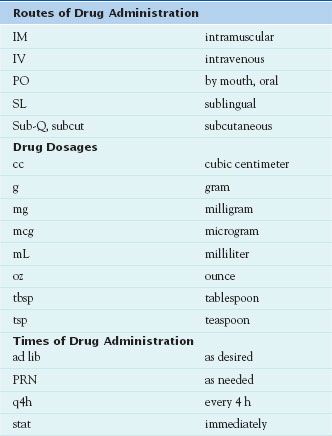

To interpret medication orders accurately, the nurse must know commonly used abbreviations for routes, dosages, and times of drug administration (Table 3.2). As a result of medication errors that occurred because of incorrect or misinterpreted abbreviations, many abbreviations that were formerly commonly used are now banned or are no longer recommended by The Joint Commission, the ISMP, and other organizations concerned with increasing patient safety. Thus, it is safer to write out such words as “daily” or “three times daily,” “at bedtime,” “ounce,” “teaspoon” or “tablespoon,” or “right,” “left,” or “both eyes” rather than using abbreviations, in both medication orders and in transcribing orders to the patient’s MAR. If the nurse cannot read the physician’s order or if the order seems erroneous, he or she must question the order before giving the drug.

NCLEX Success

6. A nurse is administering an elixir. Which of the following measures is appropriate?

A. microgram

B. milligram

C. milliliter

D. kilogram

7. The nurse has administered lacosamide (Vimpat) to the wrong patient. What is the first action the nurse should take?

A. Assess the patient’s vital signs and level of consciousness.

B. Notify the physician.

C. Fill out an incident report.

D. Call the respiratory therapist for administration of oxygen.

Drug Preparations and Dosage Forms

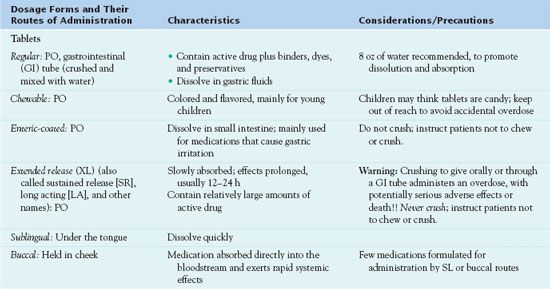

Drug preparations and dosage forms vary according to the drug’s chemical characteristics, reason for use, and route of administration. Some drugs are available in only one dosage form, and others are available in several forms. Table 3.3 and the following section describe characteristics of various dosage forms.

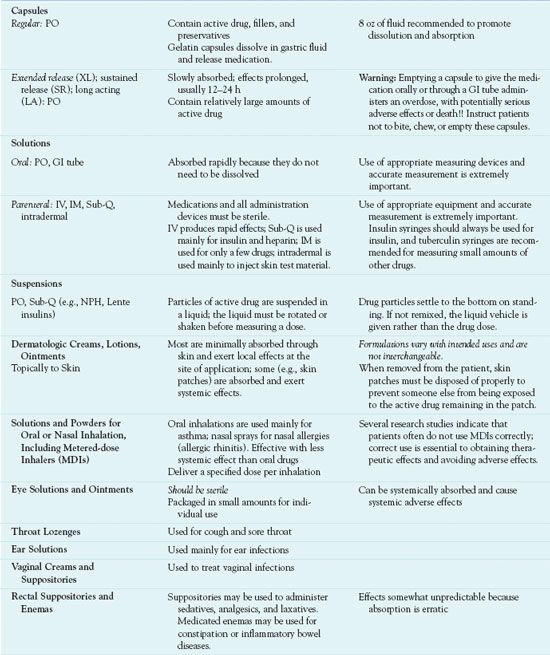

Dosage forms of systemic drugs include liquids, tablets, capsules, suppositories, and transdermal and pump delivery systems. Systemic liquids are given orally, or PO (Latin per os, “by mouth”), or by injection. Those given by injection must be sterile.

Administration of tablets and capsules is PO. Tablets contain active drug plus binders, colorants, preservatives, and other substances. Capsules contain active drug enclosed in a gelatin capsule. Most tablets and capsules dissolve in the acidic flu-ids of the stomach and are absorbed in the alkaline fluids of the upper small intestine. Enteric-coated tablets and capsules are coated with a substance that is insoluble in stomach acid. This delays dissolution until the medication reaches the intestine, usually to avoid gastric irritation or to keep the drug from being destroyed by gastric acid. Tablets for sublingual (under the tongue) or buccal (held in cheek) administration must be specifically formulated for such use.

Several controlled-release dosage forms and drug delivery systems are available, and more continue to be developed. These formulations maintain more consistent serum drug levels and allow less frequent administration, which is more convenient for patients. Controlled-release oral tablets and capsules are called by a variety of names (e.g., timed release, sustained release, extended release), and their names usually include CR, SR, XL, or other indications that they are long-acting formulations. Most of these formulations are given once or twice daily. Some drugs (e.g., alendronate for osteoporosis, fluoxetine for major depression) are available in formulations that deliver a full week’s dosage in one oral tablet. Because controlled-release tablets and capsules contain high amounts of drug intended to be absorbed slowly and act over a prolonged period of time, they should never be broken, opened, crushed, or chewed. Such an action allows the full dose to be absorbed immediately and constitutes an overdose, with potential organ damage or death. Transdermal (skin patch) formulations include systemically absorbed clonidine, estrogen, fentanyl, and nitroglycerin. These medications are slowly absorbed from the skin patches over varying periods of time (e.g., 1 week for clonidine and estrogen). Pump delivery systems may be external or implanted under the skin and refillable or long acting without refills. Pumps are used to administer insulin, opioid analgesics, antineoplastics, and other drugs.

Solutions, ointments, creams, and suppositories are applied topically to skin or mucous membranes. They are formulated for the intended route of administration. For example, several drugs are available in solutions for nasal or oral inhalation; they are usually self-administered as a spray into the nose or mouth.

Many combination products containing fixed doses of two or more drugs are also available. Commonly used combinations include analgesics, antihypertensive drugs, and cold remedies. Most are oral tablets, capsules, or solutions.

Calculating Drug Dosages

When calculating drug dosages, the importance of accuracy cannot be overemphasized. Accuracy requires basic skills in mathematics, knowledge of common units of measurement, and methods of using data in performing calculations.

Systems of Measurement

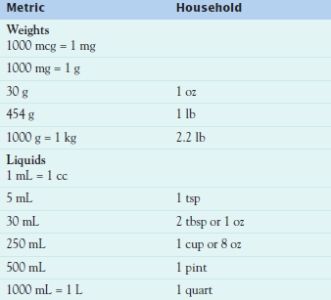

The most commonly used system of measurement is the metric system, in which the meter is used for linear measure, the gram for weight, and the liter for volume. One milliliter (mL) equals 1 cubic centimeter (cc), and both equal 1 gram (g) of water. The household system, with units of drops, teaspoons, tablespoons, and cups, is infrequently used in health care agencies but may be used at home. Table 3.4 lists some commonly used equivalent measurements.

A few drugs are ordered and measured in terms of units or milliequivalents (mEq). Units express biologic activity in animal tests (i.e., the amount of drug required to produce a particular response). Units are unique for each drug. For example, concentrations of insulin and heparin are both expressed in units, but there is no relation between a unit of insulin and a unit of heparin. These drugs are usually ordered in the number of units per dose (e.g., NPH insulin 30 units subcutaneously every morning, or heparin 5000 units subcutaneously every 12 hours) and labeled in number of units per milliliter (U 100 insulin contains 100 units/mL; heparin may have 1000, 5000, or 10,000 units/mL). Milliequivalents express the ionic activity of a drug. Drugs such as potassium chloride are ordered and labeled in the number of milliequivalents per dose, tablet, or milliliter.

Mathematical Calculations

Most drug orders and labels are expressed in metric units of measurement. If the amount specified in the order is the same as that on the drug label, no calculations are required, and preparing the right dose is a simple matter. For example, if the order reads “ibuprofen 400 mg PO” and the drug label reads “ibuprofen 400 mg per tablet,” it is clear that one tablet is to be given.

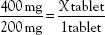

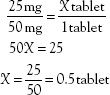

What happens if the order calls for a 400-mg dose and 200-mg tablets are available? The question is, “How many 200-mg tablets are needed to give a dose of 400 mg?” In this case, the answer can be readily calculated mentally to indicate two tablets. This is a simple example that also can be used to illustrate mathematical calculations. This problem can be solved by several acceptable methods; the following formula is presented because of its relative simplicity for students lacking a more familiar method:

D = desired dose (dose ordered, often in milligrams)

H = on hand or available dose (dose on the drug label; often in Cross multiply: mg per tablet, capsule, or milliliter)

X = unknown (number of tablets, in this example)

V = volume or unit (one tablet, in this example)

Cross multiply:

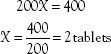

What happens if the order and the label are written in different units? For example, the order may read “amoxicillin 0.5 g” and the label may read “amoxicillin 500 mg/capsule.” To calculate the number of capsules needed for the dose, the first step is to convert 0.5 g to the equivalent number of milligrams, or convert 500 mg to the equivalent number of grams. The desired or ordered dose and the available or label dose must be in the same units of measurement. Using the equivalents (i.e., 1 g = 1000 mg) listed in Table 3.4, an equation can be set up as follows:

The next step is to use the new information in the formula, which then becomes

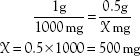

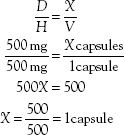

The same procedure and formula can be used to calculate portions of tablets or doses of liquids. These are illustrated in the following problems:

1. Order: 25 mg PO

Label: 50-mg tablet

2. Order: 25 mg IM

Label: 50 mg in 1 cc

3. Order: 4 mg IV

Label: 10 mg/mL

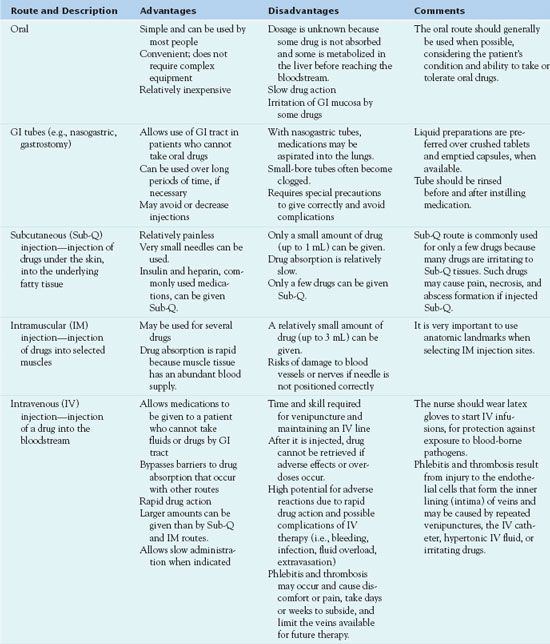

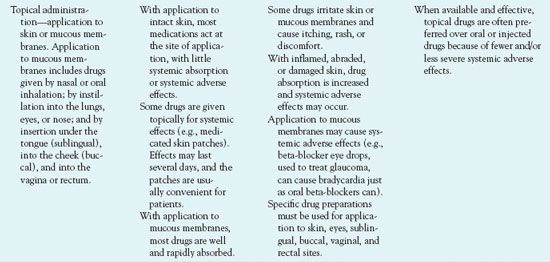

Routes of Administration

Routes of administration depend on drug characteristics, patient characteristics, and desired responses. The major routes are oral (by mouth), parenteral (injected), and topical (applied to skin or mucous membrane). Each has advantages, disadvantages, indications for use, and specific techniques of administration (Table 3.5). Common parenteral routes are subcutaneous, IM, and IV injections. Injections require special drug preparations, equipment, and techniques. The following section discusses general characteristics of the IV route, and Box 3.1 presents specific considerations.

BOX 3.1 Principles and Techniques With Intravenous Drug Therapy