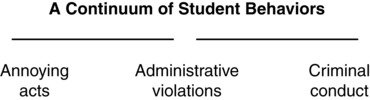

On today’s campuses of higher education, there appears to be increasing incidence of incivility among students (Clark & Springer, 2007). When preparing a learning environment for students and faculty, how can faculty ensure that it is one that is safe and productive for all, one in which a quality teaching and learning experience can be provided? This chapter introduces developmental, legal, and risk management issues related to classroom learning environments and methods to minimize student conduct that disrupts learning. Instructional strategies are discussed to assist faculty in achieving a robust and engaging learning environment through management of the students’ actions. Both faculty and students have reported that incivility is a moderate problem in nursing education (Clark, 2007, 2008a). More specifically, Lashley and deMeneses (2001) found that all faculty who responded to a survey of student misconduct in nursing had experienced students being late, inattentive, or absent from class, and more than 90% reported student cheating as a problem. In some more rare instances, faculty experience more serious episodes of misconduct, including verbal or physical abuse (Lashley & deMeneses, 2001; Luparell, 2004). Stress in both faculty and students has been identified as contributing significantly to uncivil behavior in nursing education (Clark, 2008b). While the majority of this chapter will address how student misbehavior can be managed, it is important that faculty have an appreciation for the overall context in which misconduct and incivility occur. Student misconduct and incivility rarely occur in a vacuum. In both the general workplace and in nursing education, experts suggest that incivility is reciprocal in nature (Andersson & Pearson, 1999; Clark, 2008b). If student misbehavior is viewed as a form of communication, it necessitates that we view it in a broader context that includes student interactions with faculty and the learning environment. There is evidence to suggest that faculty play a pivotal role in establishing classroom behavioral norms and also may contribute to the problem in a variety of ways. In a landmark study, Boice (1996) concluded that faculty are the most crucial initiators of incivility in the classroom. Poor teaching skills may lead to student frustration and misbehavior. Additionally, lack of instructor willingness to address classroom incivility sends a message that such behavior is acceptable. Additionally, Clark (2008a) found that students sometimes experience incivility at the hands of faculty. Students perceive condescending remarks or putdowns by faculty as uncivil. A long list of additional behaviors that students identify as uncivil on the part of faculty include exerting superiority, being unavailable outside of class, refusing or being reluctant to answer questions, canceling scheduled classes and activities without warning, ignoring disruptive behaviors, not allowing open discussion, and using ineffective teaching styles or methods. For purposes of analyzing student behaviors, all behaviors will fall within one or more of the following three categories: (1) annoying acts, (2) administrative violations, and (3) criminal conduct (Fig. 14-1). It is possible that a single behavior, such as stealing a test, can be both an administrative violation and criminal conduct. It is also possible that a behavior repeated over time, such as interrupting a lecture repeatedly, can be considered both an annoying act and an administrative violation. Occasionally a lecture disruption might be annoying, but the behavior moves from annoying to a violation of campus policy if the disruptions persist after the student has been counseled that the behavior exceeds reasonable limits. Regardless of where the behavior may lie on the continuum, it is critically important to create a teaching approach wherein faculty are in a position to observe student behaviors objectively. The focus should be on actions and not on emotion, rumor, or innuendo. Furthermore, it is important that faculty remain cognizant of student behaviors and their potential impact on learning in order to, at the earliest opportunity, consider the extent to which student actions fall within this framework. Awareness is the first step in managing the learning environment. Box 14-1 lists examples of student misconduct that fall within the categories of annoying acts, administrative violations, and criminal conduct. From a professional educational standpoint, it is important to note that these annoying acts, left unchecked, can later manifest themselves in the student’s professional workplace. Bartholomew (2006) summarizes a relatively recent body of literature that describes this set of behaviors as “horizontal hostility” or “lateral violence.” Examples of “horizontal hostility” include peers (e.g., students to students or nurses to nurses) acting uncivilly, acting abruptly, undermining individual and group efforts, withholding work-related information, and demonstrating a general lack of collegiality. As a result, clearly and consistently holding students accountable for their actions has an immediate impact on the individual as a learner and a future impact on the individual in his or her professional life. Administrative violations are behaviors that violate an administrative code of conduct. Administrative violations can be a variety of behaviors that significantly disrupt the learning process, such as acts of intimidation or harassment. These behaviors can be motivated by a desire to gain an academic advantage through scholastic misconduct, such as cheating, plagiarism, or fabricating results. Because codes or policies of student conduct are unique to each institution, it is strongly recommended that faculty acquaint themselves with the code in order to know when a student may have violated institutional policy. Chapter 3 further discusses the ethical issues related to academic dishonesty. The syllabus is historically the document that articulates the basic relationship between student and instructor. While a syllabus cannot present text for every concern, including text that expresses “the ground rules” or the rules of engagement between the instructor and students is often one way to create an environment designed to minimize conflict. Three types of suggested text are offered for your consideration in Box 14-2. The examples offered are suggestions and should be customized to support the established culture and values of your particular program and university or college.

Managing student incivility and misconduct in the learning environment

Incivility in the higher education environment

A continuum of misconduct

Annoying acts

Administrative violations

Proactive response strategies

Forewarning in the course syllabus

Managing student incivility and misconduct in the learning environment

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access